Tumors of the bronchus and lung

Risk Factors:Cigarette smoking is by far the most important cause of lung cancer. for at least 90 being proportional to the amount smoked and to the tar content of cigarettes.

The death rate from the disease in heavy smokers is 40 times that in non-smokers. Risk falls slowly after smoking cessation, but remains above that in non-smokers for many years

Exposure to naturally occurring radon is another risk.

The incidence of lung cancer is slightly higher in urban than in rural dwellers which may reflect differences in atmospheric.

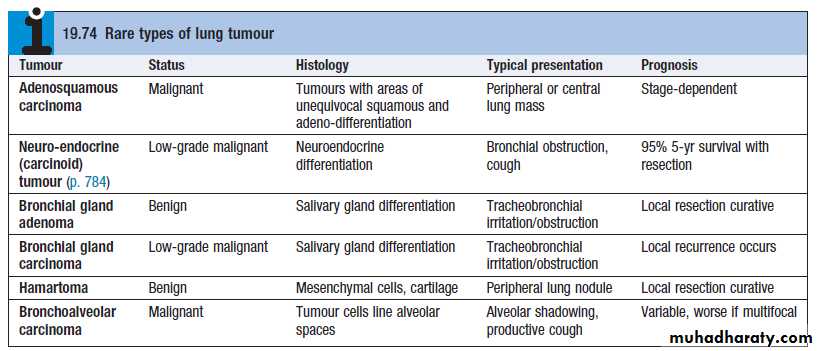

Bronchial carcinoma

The incidence of bronchial carcinoma increased dramatically during the 20th century as a direct result of the tobacco epidemic.In women, smoking prevalence and deaths from lung cancer continue to increase, and more women now die of lung cancer than breast cancer in the USA and the UK

Bronchial carcinomas arise from the bronchial epithelium or mucous glands.

The common cell types are:

Squamous 35%,Adenocarcinoma 30%,

Small-cell 20%,

Large-cell 15%.

Tumour occurs in a large bronchus, symptoms arise early, but tumours originating in a peripheral bronchus can grow very large without producing symptoms, resulting in delayed diagnosis.

Peripheral squamous tumours may undergo central necrosis and cavitation, and may resemble a lung abscess on X-ray .

Spread

Bronchial carcinoma may involve the pleura either directly or by lymphatic spread and may extend into the chest wall, invading the intercostal nerves or the brachial plexus and causing pain.Lymphatic spread to mediastinal and supraclavicular lymph nodes frequently occurs prior to diagnosis.

Blood-borne metastases occur most commonly in liver, bone, brain, adrenals and skin. Even a small primary tumour may cause widespread metastatic deposits and this is a particular characteristic of small-cell lung cancers.

Clinical Presentation of Bronchial carcinoma

Cough: The most common early symptom, cough is often dry; however, secondary infection may cause purulent sputum. A change in the character of a smoker's cough, particularly if associated with other new symptoms, should always raise suspicion of bronchial carcinoma.

Haemoptysis: This is common, especially with central bronchial tumours. Although it may be benign, haemoptysis in a smoker should always be investigated to exclude a bronchial carcinoma.

Occasionally, central tumours invade large vessels, causing sudden massive haemoptysis which may be fatal

Bronchial obstruction: The clinical and radiological manifestations depend on the site and extent of the obstruction, any secondary infection, and the extent of coexisting lung disease.

Complete obstruction: causes collapse of a lobe or lung, with breathlessness, mediastinal displacement and dullness to percussion with reduced breath sounds.

Partial bronchial obstruction: may cause a monophonic, unilateral wheeze that fails to clear with coughing and may also impair the drainage of secretions sufficiently to cause pneumonia or lung abscess as a presenting problem.

Pneumonia: that recurs at the same site or responds slowly to treatment, particularly in a smoker, should always suggest an underlying bronchial carcinoma.

Stridor: (a harsh inspiratory noise) occurs when the lower trachea, carina or main bronchi are narrowed by the primary tumour or by compression from malignant enlargement of the subcarinal and paratracheal lymph nodes.

Breathlessness: This may be caused by collapse or pneumonia, or by tumour causing a large pleural effusion or compressing a phrenic nerve causing diaphragmatic paralysis.

Pain and nerve entrapment: Pleural pain usually indicates malignant pleural invasion, although it can occur with distal infection. Intercostal nerve involvement causes pain in the distribution of a thoracic dermatome.

Carcinoma in the lung apex: may cause Horner's syndrome (ipsilateral partial ptosis, enophthalmos, miosis and hypohidrosis of the face due to involvement of the sympathetic chain at or above the stellate ganglion.

Pancoast's syndrome: pain in the shoulder and inner aspect of the arm, sometimes with small muscle wasting in the hand indicates malignant destruction of the T1 and C8 roots in lower part of the brachial plexus by an apical lung tumour.

Mediastinal spread: Involvement of the oesophagus may cause dysphagia.

If the pericardium is invaded, arrhythmia or pericardial effusion may occur.

Superior vena cava obstruction by malignant nodes causes suffusion and swelling of the neck and face, conjunctival oedema, headache and dilated veins on the chest wall, and is most commonly due to bronchial carcinoma.

Involvement of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve by tumours at the left hilum causes vocal cord paralysis, voice alteration and a 'bovine' cough (lacking the normal explosive character).

Supraclavicular lymph nodes may be palpably enlarged; if so, a needle aspirate may provide a simple means of cytological diagnosis.

Metastatic spread: This may lead to focal neurological defects, epileptic seizures, personality change, jaundice, bone pain or skin nodules. Lassitude, anorexia and weight loss usually indicate metastatic spread.

Digital clubbing. Overgrowth of the soft tissue of the terminal phalanx leading to increased nail curvature is often seen.

This may be associated with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA), characterised by periostitis of the long bones, most commonly the distal tibia, fibula, radius and ulna.

This causes pain and tenderness over the affected bones and often pitting oedema over the anterior aspect of the shin. X-rays reveal subperiosteal new bone formation. While most frequently associated with bronchial carcinoma, HPOA can occur with other tumours.

Non-metastatic extrapulmonary effects .Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and ectopic adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion are usually associated with small-cell lung cancer

Hypercalcaemia is usually caused by squamous cell carcinoma.

Associated neurological syndromes may occur with any type of bronchial carcinoma

Non-metastatic extrapulmonary manifestations of bronchial carcinoma

Endocrine

Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion causing hyponatraemia

Ectopic adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion

Hypercalcaemia due to secretion of parathyroid hormone-related peptides

Carcinoid syndrome

Gynaecomastia

Neurological

Polyneuropathy

Myelopathy

Cerebellar degeneration

Myasthenia (Lambert-Eaton syndrome).

Other

Digital clubbing

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

Nephrotic syndrome

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis

Eosinophilia

Investigations for Bronchial carcinoma

Plain X-rays

CT is usually performed for :

localization,operability, metastatic spread

and for accessible or not by bronchoscopy .

Bronchoscopy: three-quarters of primary lung tumours can be visualised and sampled directly by biopsy and brushing using a flexible bronchoscope.

Percutaneous needle biopsy under CT or ultrasound guidance; more reliable way to obtain a histological diagnosis for tumours which are too peripheral

Common radiological presentations of bronchial carcinoma

Unilateral hilar enlargementPeripheral pulmonary opacity

Lung, lobe or segmental collapse

Pleural effusion

Broadening of mediastinum

Enlarged cardiac shadow

Elevation of a hemidiaphragm

Rib destruction

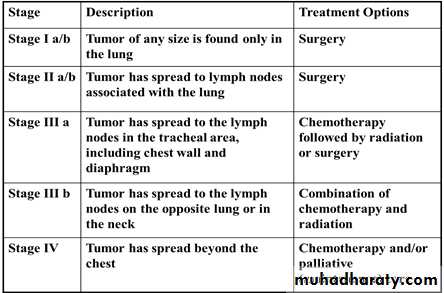

Staging to guide treatment

The propensity of small-cell lung cancer to metastasise early dictates that patients with this tumour type are usually not suitable for surgical intervention.

In patients with other cell types, subsequent investigations should focus on determining whether the tumour is operable, because complete resection may be curative.

While CT may show obvious spread of disease, for many patients the results are equivocal and further investigation is required before deciding whether curative surgery is feasible.

Enlarged upper mediastinal nodes may be sampled by using a bronchoscope equipped with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) or by mediastinoscopy.

Nodes in the lower mediastinum can be sampled through the oesophageal wall using endoscopic ultrasound.

Combined CT and PET imaging is used increasingly to detect metabolically active tumour metastases.

Head CT, radionuclide bone scanning, liver ultrasound and bone marrow biopsy are generally reserved for patients with clinical, haematological or biochemical evidence of tumour spread to such sites.

Finally, detailed physiological testing is required to ensure that the patient's respiratory and cardiac function is sufficient to allow surgical treatment.

Contraindications to surgical resection in bronchial carcinoma

Distant metastasis (M1)

Invasion of central mediastinal structures including heart, great vessels, trachea and oesophagus (T4)

Malignant pleural effusion (T4)

Contralateral mediastinal nodes (N3)

FEV1 < 0.8 L

Severe or unstable cardiac or other medical condition

Management

Surgical resection carries the best hope of long-term survival; however, some patients treated with radical radiotherapy and chemotherapy also achieve prolonged remission or cure.Unfortunately, in over 75% of cases, treatment with curative intent is not possible, or is inappropriate due to extensive spread or comorbidity. Such patients can only be offered palliative therapy and best supportive care.

Radiotherapy, and in some cases chemotherapy, can relieve distressing symptoms.

Treatment and Staging NSCLC

Surgical treatment: Accurate pre-operative staging, coupled with improvements in surgical and post-operative care, now offers 5-year survival rates of over 75% in stage I disease (N0, tumour confined within visceral pleura) and 55% in stage II disease, which includes resection in patients with ipsilateral peribronchial or hilar node involvement.

Radiotherapy : While much less effective than surgery, radical radiotherapy can offer long-term survival in selected patients with localised disease in whom comorbidity precludes surgery.

The greatest value of radiotherapy, however, is in the palliation of distressing complications such as superior vena cava obstruction, recurrent haemoptysis, and pain caused by chest wall invasion or by skeletal metastatic deposits.

Obstruction of the trachea and main bronchi can also be relieved temporarily.

Radiotherapy can be used in conjunction with chemotherapy in the treatment of small-cell carcinoma, and is particularly efficient at preventing the development of brain metastases in patients who have had a complete response to chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy: The treatment of small-cell carcinoma with combinations of cytotoxic drugs, sometimes in combination with radiotherapy, can increase the median survival from 3 months to well over a year.

Combination chemotherapy leads to better outcomes than single-agent treatment.

In general, chemotherapy is less effective in non-small-cell bronchial cancers. However, studies in such patients using platinum-based chemotherapy regimens have shown a 30% response rate associated with a small increase in survival.

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy : In non-small-cell carcinoma, there is some evidence that chemotherapy given before surgery may increase survival and can effectively 'down-stage' disease with limited nodal spread.

Post-operative chemotherapy is now proven to improve survival rates when operative samples show nodal involvement by tumour.

Laser therapy and stenting : Palliation of symptoms caused by major airway obstruction can be achieved in selected patients using bronchoscopic laser treatment to clear tumour tissue and allow re-aeration of collapsed lung.

The best results are achieved in tumours of the main bronchi. Endobronchial stents can be used to maintain airway patency in the face of extrinsic compression by malignant nodes.

Prognosis : The overall prognosis in bronchial carcinoma is very poor, with around 70% of patients dying within a year of diagnosis and only 6-8% of patients surviving 5 years after diagnosis. The best prognosis is with well-differentiated squamous cell tumours that have not metastasised and are amenable to surgical resection.

Secondary tumours of the lung

Blood-borne metastatic deposits in the lungs may be derived from many primary tumours, in particular those of the breast, kidney, uterus, ovary, testes and thyroid.The secondary deposits are usually multiple and bilateral.

Often there are no respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis is made on radiological examination.

Breathlessness may occur if a considerable amount of lung tissue has been replaced by metastatic tumour.

Endobronchial deposits are uncommon but can cause haemoptysis and lobar collapse.