1

Inguinal hernia

The most common hernia in men and women. Its types:

Lateral (oblique, indirect), congenital

Medial (direct), acquired hernia

Sliding

Walls of the Inguinal Canal

The anterior wall of the canal is: formed along its entire length by the aponeurosis

of the external oblique. It is reinforced in its lateral third by the origin of the

internal oblique from the inguinal ligament. This wall is therefore strongest where

it lies opposite the weakest part of the posterior wall namely the deep inguinall

ring.

The posterior wall of the canal is formed along its tire length by the fascia

transversalis. It is reinforced in its' the tendon Of 9 third by the conjoint tendon,

the common tendon of insertion Of the internal Oblique and transversus which is

attached to the pubic crest and pectineal line. This wall is therefore strongest

where it lies opposite the weakest part of the anterior wall namely the superficiall

inguinal ring.

The inferior wall or floor Of the canal is formed by the rolled-under inferior edge

of the of the external oblique muscle, namely the inguinal ligament and at its

medial end, the lacunar ligament.

The inguinal canal

In the male contains the testicular artery, veins, lymphatics and the vas deferens.

In the female, the round ligament descends through the canal to end in the vulva.

Three important nerves: the ilioinguinal, the iliohypogastric and the genital branch

of the genitofemoral nerve also pass through the canal.

As the testis descends, a tube of peritoneum is pulled with the testis and wraps

around it ultimately to form the tunica vaginalis.

2

This peritoneal tube should obliterate ,fails to fuse either in part or totally, Inguinal

hernia in neonates and young children is always of this congenital type

An indirect hernia is lateral as its origin is lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels

Direct inguinal hernia

The second type of inguinal hernia, referred to as direct or medial, is acquired

It is a result of stretching and weakening of the abdominal wall just medial to the

inferior epigastric (IE).

Hasselbach’s triangle, whose three sides are the IE vessels laterally, the lateral

edge of the rectus abdominus muscle medially and the pubic bone below

This area is weak as the abdominal wall here only consists of transversalis fascia

covered by the external oblique aponeurosis.

More likely in elderly

Unlikely to strangulate

Sliding hernia.

Acquired hernia due to weakening of the

Abdominal wall but this occurs at the deep inguinal ring lateral to the IE vessels.

However the sac has formed secondarily

On the left side, sigmoid colon may be pulled into a sliding hernia and on the right

side the caecum

Occasionally, both lateral and medial hernias are present in the same patient

(pantaloon hernia).

Classification

The European Hernia Society has recently suggested a simplified system of:

• Primary or recurrent (P or R);

• Lateral, medial or femoral (L, M or F);

• Defect size in finger breadths assumed to be 1.5 cm.

A primary, indirect, inguinal hernia with a 3-cm defect size would be PL2.

Diagnosis of an inguinal hernia

Usually these hernias are reducible presenting as intermittent swellings, lying

above and lateral to the pubic tubercle with an associated cough impulse

If an inguinal hernia becomes irreducible and tense there may be no cough

impulse

Require urgent investigation by either ultrasound or CT scan

Differential diagnosis

3

1. lymph node groin mass

2. abdominal mass

3. hydrocoele

4. testicular swelling.

5. saphena varix

6. varicocoele.

Management of inguinal hernia

Herniotomy and herniorrhaphy

Open suture repair

Sutures are now placed between the conjoint tendon above and the inguinal

ligament below(Bassini’s repair)

Open flat mesh repair

Lowered hernia recurrence rates and accelerated postoperative recovery

Open plug/device/complex mesh repair

Emergency inguinal hernia surgery only 5 per cent present as an emergency with a

painful irreducible hernia which may progress to strangulation and possible bowel

infarction.

Complications of inguinal hernia surgery

Immediate complications

Bleeding (which may be due to accidental

Damage to the inferior epigastric or iliac vessels)

Urinary retention

Anesthetic related

Next week: Seroma formation and wound infection

In the longer term: hernia recurrence and chronic pain

Evidence shows that mesh repairs have lower recurrence rates than suture

repairs

Damage to the testicular artery can lead to testicular infarction

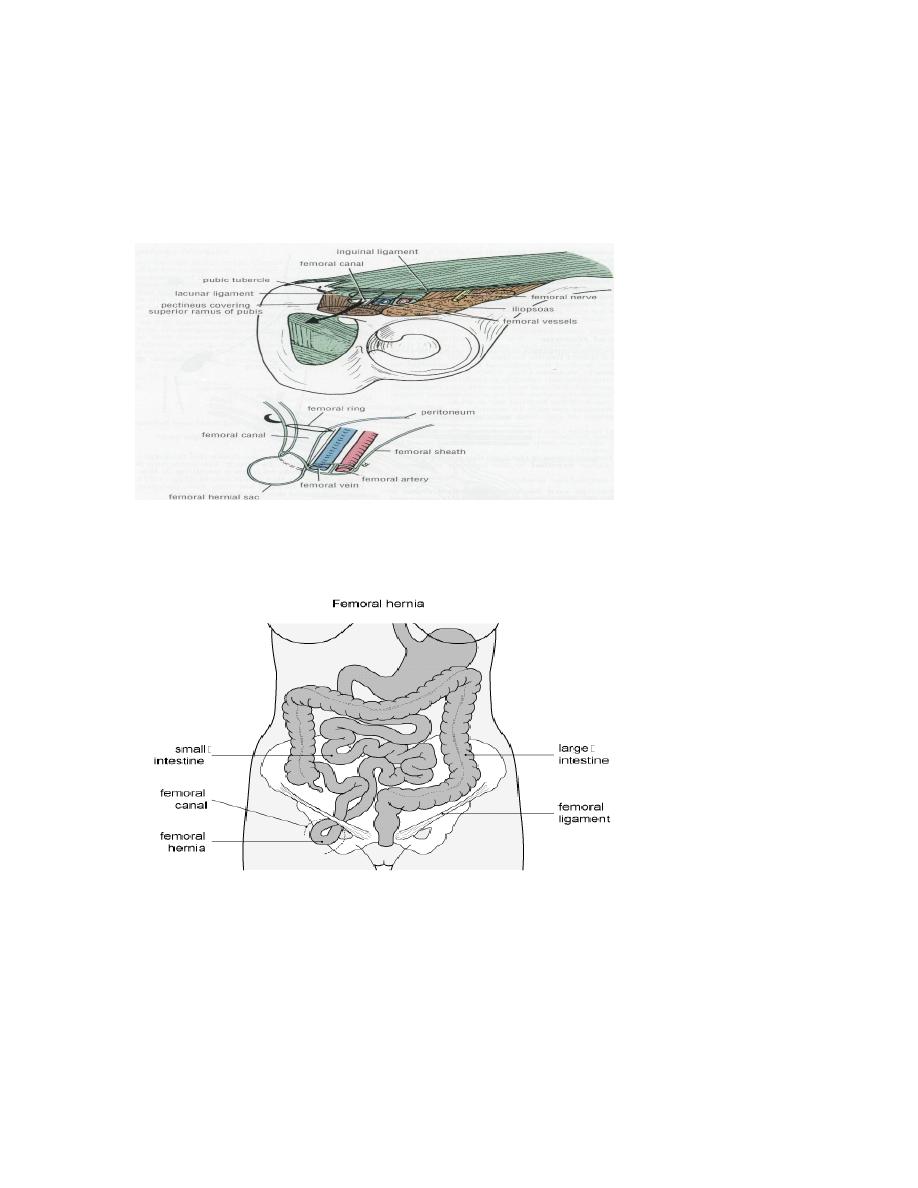

Femoral hernia

The iliac artery and vein pass below the inguinal ligament to become the femoral

vessels in the leg. The vein lies medially and the artery just lateral to the vein with

the femoral nerve lateral to the artery.

Just medial to the vein is a small space containing fat and some lymphatic tissue

(node of Cloquet).

This space which is exploited by a femoral hernia

4

The walls of a femoral hernia are the femoral vein laterally,the inguinal ligament

anteriorly, the pelvic bone covered by theileopectineal ligament (Astley Cooper’s)

posteriorly and the lacunar ligament (Gimbernat’s) medially

Diagnosis of femoral hernia

Less common than inguinal hernia

It is more common in females than in males

Easily missed on examination

Fifty per cent of cases present as an emergency with very high risk of strangulation

5

The hernia appears below and lateral to the pubic tubercle and lies in the upper leg

rather than in the lower abdomen.

The hernia often rapidly becomes irreducible and loses any cough impulse due to

the tightness of the neck.

Easily be mistaken for a lymph node

If there is uncertainly then ultrasound or CT should be requested.

Plain x-ray

Differential diagnosis

1. Direct inguinal hernia

2. Lymph node

3. Saphena varix

4. Femoral artery aneurysm

5. Psoas abscess

6. Rupture of adductor longus with haematoma

Surgery for femoral hernia

1. Low approach (Lockwood

2. The inguinal approach (Lotheissen

3. High approach (McEvedy

4. Laparoscopic approach

6

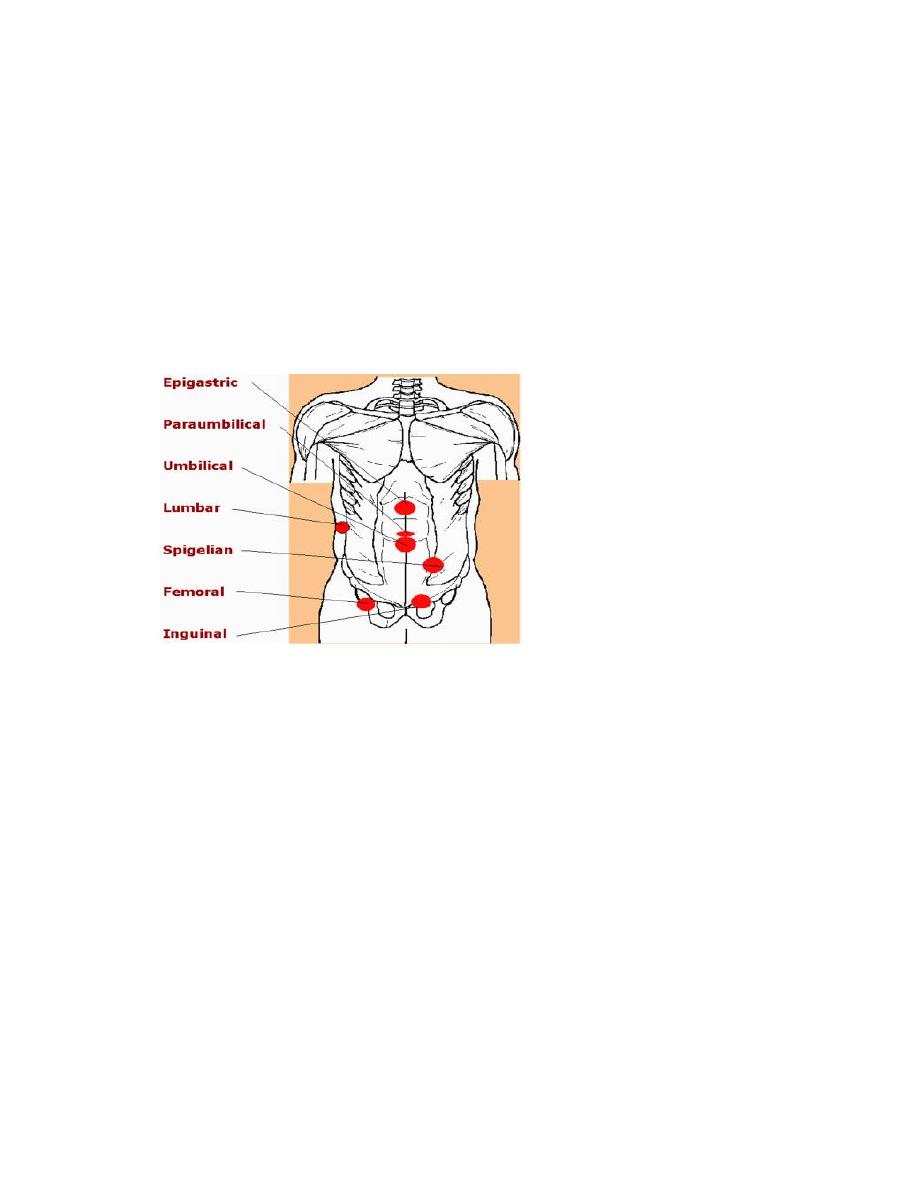

Ventral hernia

1. Umbilical – paraumbilical

2. Epigastric

3. Incisional

4. Parastomal

5. Spigelian

6. Lumbar

7. Traumatic

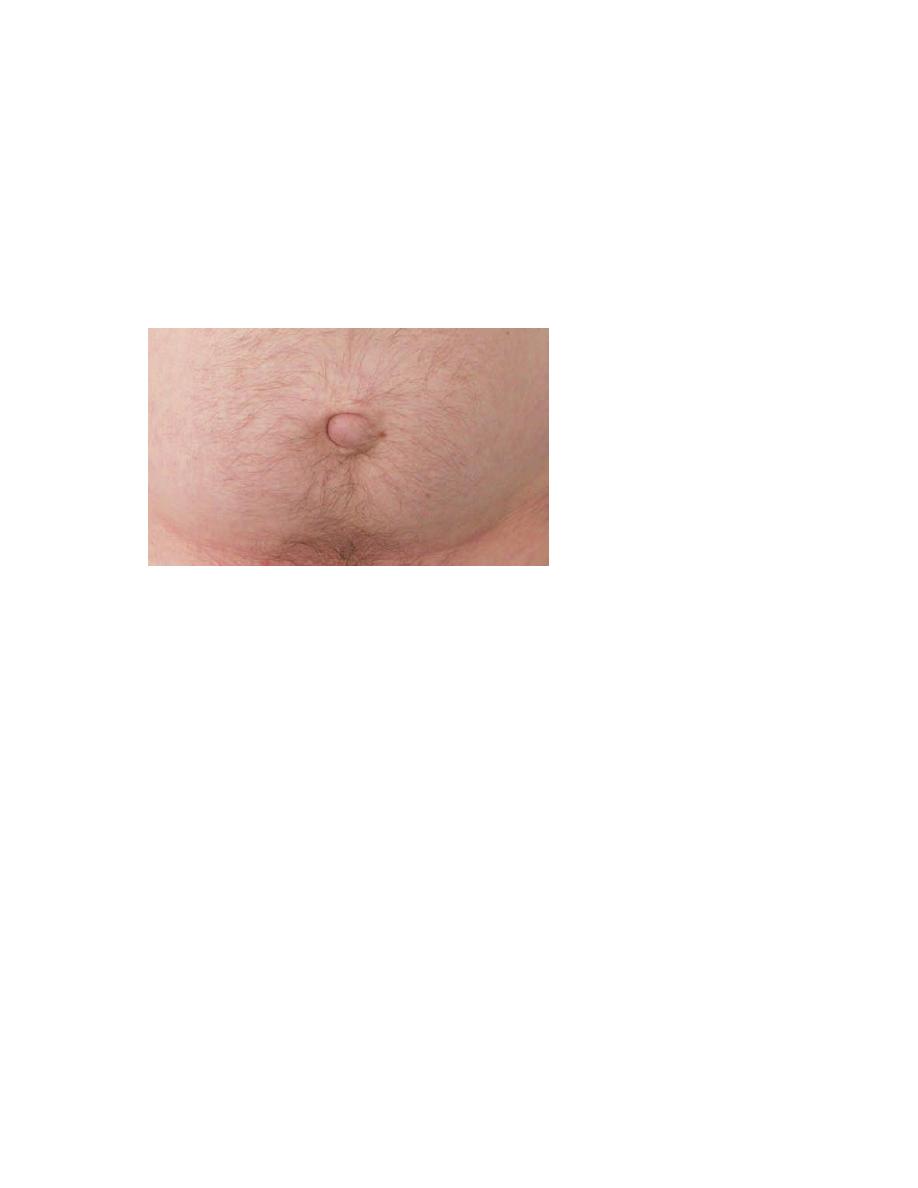

Umbilical hernia

The umbilical defect is present at birth but closes as the stump of the umbilical

cord heals, usually within a week of birth.

This process may be delayed, leading to the development of herniation in the

neonatal period.

Umbilical hernia in adults

Conditions which cause stretching and thinning of the midline raphe (linea alba),

such as pregnancy, obesity and liver disease with cirrhosis, predispose to

reopening of the umbilical defect

Small umbilical hernias often contain extraperitoneal fat or omentum. Larger

hernias can contain small or large bowel

7

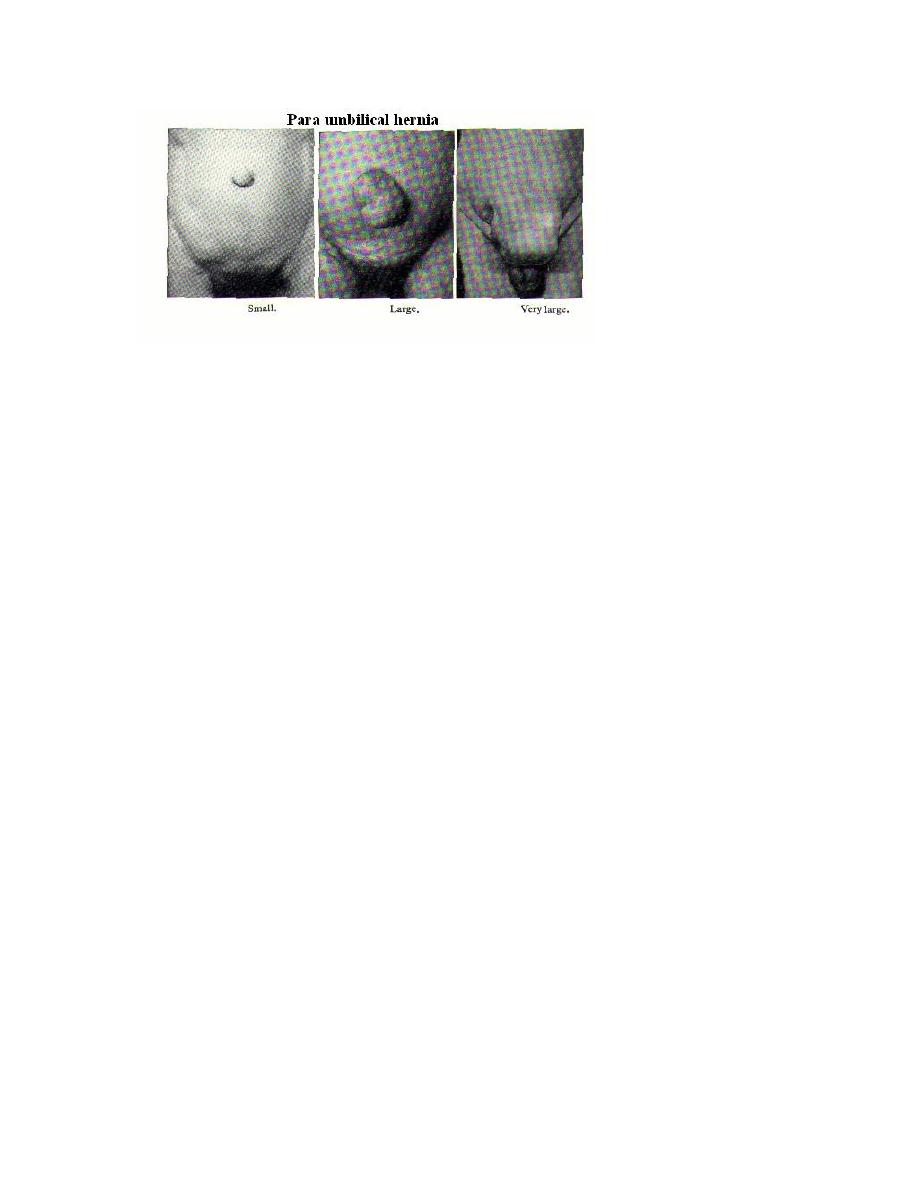

Clinical features

Commonly overweight

The bulge is typically slightly to one side of

the umbilical depression, creating a crescent-shaped appearance to the umbilicus

Women are affected more

Pain due to tissue tension or symptoms of intermittent bowel obstruction

Overlying skin may become thinned,stretched and develop dermatitis.

Treatment

Because of the high risk of strangulation, operation should be advised in cases

where the hernia contains bowel

Surgery may be performed open or laparoscopically.

Open umbilical hernia repair: for defects larger than 2 cm in diameter, mesh

repair is recommended

The mesh may be placed in one of several anatomical planes:

Within the peritoneal cavity

In the retromuscular space

In the extraperitoneal space

In the subcutaneous plane (onlay mesh)

8

Epigastric hernia

• arise through the midline raphe (linea alba) anywhere between the

xiphoid process and the umbilicus, usually midway

• begin with a transverse split

• in contrast to umbilical hernias, the defect

is elliptical.

• defect occurs at the site where small blood vessels pierce the linea

alba

• More likely, that it arises at weaknesses due to abnormal decussation

of aponeurotic fibres related to heavy physical activity

• Epigastric hernia defects are usually less than 1 cm in maximum

diameter

• commonly contain only extraperitoneal fat

• gradually enlarges, spreading in the subcutaneous plane to resemble

the shape of a mushroom.

• When very large they may contain a peritoneal sac but rarely any

bowel.

• More than one hernia may be present.

Clinical features

• patients are often fit, healthy males between 25 and 40 years of age.

• can be very painful

• The pain may mimic that of a peptic ulcer

soft midline swelling

• unlikely to be reducible because of the narrow neck

• A cough impulse may or may not be felt.

9

• Very small epigastric hernias disappear

Spontaneously

• surgery should only be offered if the hernia

is sufficiently symptomatic.

• open or laparoscopic surgery

Incisional hernia

• These arise through a defect in the musculofascial layers of the

abdominal wall in the region of a postoperative scar

• Incidence 10–50 per cent after surgery

1–5 per cent of laparoscopic port-site

incisions.

Predisposing Factors

• Patient factors (obesity, general poor healing due to malnutrition,

immunosuppression or steroid therapy, chronic cough, cancer

• wound factors (poor quality tissues, wound infection)

• Surgical factors (inappropriate suture material, incorrect suture

placement

• starts as disruption of the musculofascial

layers of a wound in the early postoperative period.

• The classic sign of wound disruption is a serosanguinous discharge.

Clinical features

• localized swelling involving a small portion of the scar but may

present as a diffuse bulging of the whole length of the incision

• increase steadily in size with time

• Strangulation is less frequent ,incisional hernias are broad-necked

Treatment

• Asymptomatic incisional hernias may not require treatment at all.

The wearing of an abdominal binder or belt may prevent the hernia

from increasing in size.

Principles of surgery

• The repair should cover the whole length of the previous incision.

• Approximation of the musculofascial layers should be done with

minimal tension

• prosthetic mesh should be used

• Mesh may be contraindicated in a contaminated field,

10

Operations

• Open repair

• Retromuscular sublay mesh repair

• Laparoscopic repair