Malaria

PROTOZOAL INFECTIONSBlood Tissues Gastrointestinal tract

Malaria Leishmaniasis GiardiasisTrypanosomiasis Toxoplasmosis Amoebiasis Cryptosporidiosis

Human malaria can be caused by four species of the genus Plasmodium:

P. falciparum,P. vivax,

P. ovale,

P. malariae.

Epidemiology

Malaria is transmitted by the bite of female anopheline mosquitoes.The disease occurs in endemic or epidemic form throughout the tropics and subtropics

Malaria can be transmitted:

• in contaminated blood transfusions

• injecting drug users sharing needles and as a hospital-acquired infection related to contaminated equipment.

• mosquitoes are transported from endemic areas ('airport malaria'), or when the local mosquito population becomes infected by a returning traveller.

Parasitology

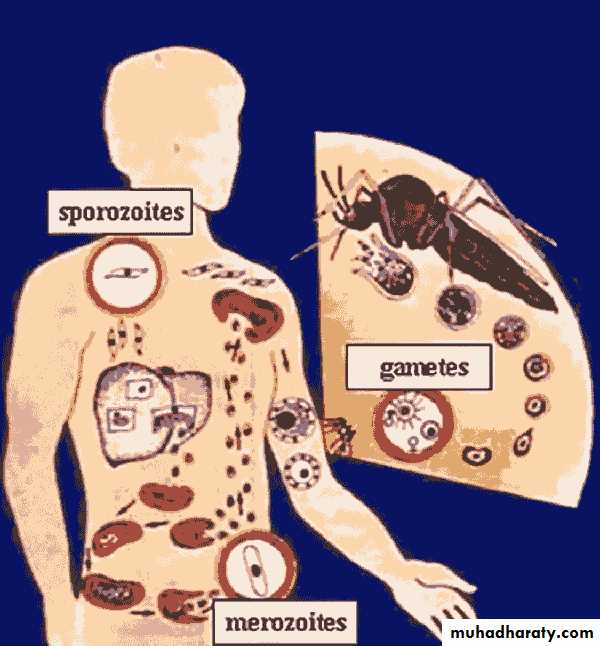

The female mosquito becomes infected after taking a blood meal containing gametocytes,(the sexual form of the malarial parasite)The developmental cycle in the mosquito usually takes 7-20 days (depending on temperature),

culminating in infective sporozoites migrating to the insect's salivary glands.

The sporozoites are inoculated into a new human host, and those which are not destroyed by the immune response are rapidly taken up by the liver.

Here they multiply inside hepatocytes as merozoites: this is pre-erythrocytic (or hepatic) sporogeny.

After a few days the infected hepatocytes rupture, releasing merozoites into the blood from where they are rapidly taken up by erythrocytes.

In the case of P. vivax and P. ovale, a few parasites remain dormant in the liver as hypnozoites. These may reactivate at any time subsequently, causing relapsing infection.

Inside the red cells the parasites again multiply, changing from merozoite, to trophozoite, to schizont, and finally appearing as 8-24 new merozoites.

The erythrocyte ruptures, releasing the merozoites to infect further cells. Each cycle of this process, which is called erythrocytic schizogony, takes about 48 hours in P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. ovale, and about 72 hours in P. malariae. P. vivax and P. ovale mainly attack reticulocytes and young erythrocytes, while P. malariae tends to attack older cells; P. falciparum will parasitize any stage of erythrocyte. A few merozoites develop not into trophozoites but into gametocytes.

These are not released from the red cells until taken up by a feeding mosquito to complete the life cycle.

Pathogenesis

The anaemia seen in malaria is multifactorial: In P. falciparum malaria, red cells containing schizonts adhere to the lining of capillaries in the brain, kidneys, gut, liver and other organs. As well as causing mechanical obstruction these schizonts rupture, releasing toxins and stimulating further cytokine release.. Causes of anaemia in malaria

infectionHaemolysis of infected red cells

Haemolysis of non-infected red cells (blackwater fever)

Dyserythropoiesis

Splenomegaly and sequestration

Folate depletion

. People who lack the Duffy antigen on the red cell membrane (a common finding in West Africa) are not susceptible to infection with P. vivax.

Certain haemoglobinopathies (including sickle cell trait) also give some protection against the severe effects of malaria: this may account for the persistence of these otherwise harmful mutations in tropical countries.

Iron deficiency may also have some protective effect. The spleen appears to play a role in controlling infection, and splenectomized people are at risk of overwhelming malaria.

Some individuals appear to have a genetic predisposition for developing cerebral malaria following infection with P. falciparum. Pregnant women are especially susceptible to severe disease.

Clinical features

Typical malaria is seen in non-immune individuals. This includes children in any area, adults in hypoendemic areas, and any visitors from a non-malarious region.

The normal incubation period is 10-21 days, but can be longer.

The most common symptom is fever, although malaria may present initially with general malaise, headache, vomiting, or diarrhoea.

At first the fever may be continual or erratic: the classical tertian or quartan fever only appears after some days.

The temperature often reaches 41°C, and is accompanied by rigors and drenching sweats

.

P. vivax or P. ovale and P. malariae infection

The illness is relatively mild.Anaemia develops slowly,

there may be tender hepatosplenomegaly.

Spontaneous recovery usually occurs within 2-6 weeks, but hypnozoites in the liver can cause relapses for many years after infection.

Repeated infections often cause chronic ill health due to anaemia and hyperreactive splenomegaly

In children, P. malariae infection is associated with glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome.

P. falciparum infection

a self-limiting illness similar to the other types of malaria, although the paroxysms of fever are usually less marked.cause serious complications

vast majority of malaria deaths are due to P. falciparum.

Patients can deteriorate rapidly, progress to coma and death within hours.

A high parasitaemia (> 1% of red cells infected) is an indicator of severe disease,

Cerebral malaria is marked by diminished consciousness, confusion, and convulsions, often progressing to coma and death. Untreated it is universally fatal.

Blackwater fever is due to widespread intravascular haemolysis, affecting both parasitized and unparasitized red cells, giving rise to dark urine.

features of severe falciparum malaria

Cerebral malaria (coma convulsion)

Renal ,Haemoglobinuria (blackwater fever) ,Oliguria

Uraemia (acute tubular necrosis)

Blood

Severe anaemia (haemolysis and dyserythropoiesis)

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

Respiratory Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Metabolic Hypoglycaemia (particularly in children)

Metabolic acidosis

Gastrointestinal/liver Diarrhoea ,Jaundice ,Splenic rupture

Other Shock - hypotensive ,Hyperpyrexia

Diagnosis

. identifying parasites on a Giemsa-stained thick or thin blood film (thick films are more difficult to interpret, and it may be difficult to speciate the parasite, but they have a higher yield).At least three films should be examined

An alternative microscopic method is quantitative buffy coat analysis (QBC), in which the centrifuged buffy coat is stained with a fluorochrome which 'lights up' malarial parasites.

A number of antigen-detection methods for identifying malarial proteins and enzymes have been developed. Some of these are available in card or dipstick form, and are potentially suitable for use in resource-poor settings.

Serological tests are of no diagnostic value.

Further investigation, including a lumbar puncture, may be needed to exclude bacterial infection.

Hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly (tropical splenomegaly syndrome, TSS)

This is seen in older children and adults in areas where malaria is hyperendemic. It is associated with an exaggerated immune response to repeated malaria infections,

is characterized by anaemia, massive splenomegaly, and elevated IgM levels. Malaria parasites are scanty or absent.

TSS usually responds to prolonged treatment with prophylactic antimalarial drugs.

Treatment

Type of malaria Drug treatmentPlasmodium vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, Chloroquine: 600 mg CQ-sensitive P. falciparum 300 mg 6 hours later 300 mg 24 hours later 300 mg 24 hours later

CQ-resistant, SP-sensitive P. falciparum Fansidar (SP): 3 tablets as single dose

CQ- and SP-resistant P. falciparum Quinine: 600 mg 3 times daily for 7 days plus

Tetracycline: 500 mg 4 times daily for 7 days or Fansidar (SP): 3 tablets as single dose

Alternative therapies

Mefloquine: 20 mg/kg in 2 doses 8 hours apart or

Malarone: 4 tablets daily for 3 days or

Coartemether: 4 tablets 12-hourly for 3 days \

or Lapdap (chlorproguanil/dapsone)

Following successful treatment of P. vivax or P. ovale malaria, it is necessary to give a 2- to 3-week course of primaquine (15 mg daily)

why? to eradicate the hepatic hypnozoites and prevent relapse.

This drug can precipitate haemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency

Drug treatment of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria in adults

CQ-sensitive P. falciparum

Chloroquine: 10 mg/kg infused over 8 hours, followed by 15 mg/kg over 24 hours

Chloroquine: 2.5 mg/kg every 4 hours by intramuscular injection (to total of 25 mg/kg)

Chloroquine: by nasogastric tube (as in oral regimen)

Fluid ,blood transfusion .oxygen therapy

Malaria prophylaxis for adult travellers

Area visited Prophylactic regimen AlternativesNo chloroquine resistance Chloroquine 300 mg weekly Proguanil 200 mg daily

(Tab.150 mg)

Significant chloroquine resistance Mefloquine 250 mg weekly Doxycycline100mg

or Malarone 1 tablet dailyLeishmaniasis

Leishmania species causing visceral and cutaneous disease in manVisceral leishmania L. donovani

Cutaneous leishmania L. tropica L.

Mucocutaneous leishmania L. braziliensis

transmitted by the bite of the female phlebotomine sandfly

Leishmaniasis is seen in localized areas of Africa, Asia (particularly India and Bangladesh), Europe, the Middle East and South and Central America. Certain parasite species are specific to each geographical area.

The clinical picture is dependent on the species of parasite, and on the host's cell-mediated immune response.

Asymptomatic infection, in which the parasite is suppressed or eradicated by a strong immune response, is common in endemic areas, as demonstrated by a high incidence of positive leishmanin skin tests.

Symptomatic infection may be confined to the skin (sometimes with spread to the mucous membranes), or widely disseminated throughout the body (visceral leishmaniasis). Relapse of previously asymptomatic infection may be seen in patients who become immunocompromised, especially those with HIV infection.

In some areas leishmania is primarily zoonotic, whereas in others, man is the main reservoir of infection.

In the vertebrate host the parasites are found as oval amastigotes (Leishman-Donovan bodies). These multiply inside the macrophages and cells of the reticuloendothelial system, and are then released into the circulation as the cells rupture.

Parasites are taken into the gut of a feeding sandfly (genus Phlebotomus in the Old World. These migrate to the salivary glands of the insect, where they can be inoculated into a new host.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Clinical featuresVisceral leishmaniasis (kala azar) is caused by L. donovani, localized areas of Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean littoral and South America. In India, where man is the main host,

The main animal reservoirs in Europe and Asia are dogs and foxes, while in Africa it is carried by various rodents.

The incubation period is usually 1-2 months, but may be several years.

The onset of symptoms is insidious, and the patient may feel quite well despite markedly abnormal physical findings. Fever is common, and although usually low-grade, it may be high and intermittent. The liver, and especially the spleen, become enlarged; lymphadenopathy is common in African kala azar. The skin becomes rough and pigmented. If the disease is not treated, profound pancytopenia develops, and the patient becomes wasted and immunosuppressed. Death usually occurs within a year, and is normally due to bacterial infection or uncontrolled bleeding.

Diagnosis

Specific diagnosis is made by demonstrating the parasite in stained smears of aspirates of bone marrow, lymph node, spleen or liver.The organism can also be cultured from these specimens.

Specific serological tests are positive in 95% of cases.

Pancytopenia, hypoalbuminaemia and hypergammaglobulinaemia are common.

The leishmanin skin test is negative, indicating a poor cell-mediated immune response

Management

The most widely used drugs for visceral leishmaniasis are the pentavalent antimony salts (e.g. sodium stibogluconate, which contains 100 mg of antimony per mL), given intravenously or intramuscularly at a dose of 20 mg of antimony per kg for 21 days.

In India, meglumine antimonate is used.

Resistance to antimony salts is increasing, and relapses may occur following treatment. The drug of choice where resources permit is intravenous amphotericin B (preferably given in the liposomal form). However, this drug is expensive and not widely available in many areas where the disease is prevalent.

Intravenous pentamidine is also effective,

and an oral drug, miltefosine, has been shown in India to be highly effective.

Intercurrent bacterial infections are common and should be treated with antibiotics.

Blood transfusion may occasionally be required.

Successful treatment may be followed in a small proportion of patients by a skin eruption called post-kala azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). It starts as a macular maculopapular nodular rash which spreads over the body. It is most often seen in the Sudan and India. Current trials are looking at the use of miltefosine for treating PKDL.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by a number of geographically localized species, which may be zoonotic or anthroponotic.Following a sandfly bite, leishmania amastigotes multiply in dermal macrophages. The local response depends on the species of leishmania, the size of the inoculum, and the host immune response. Single or multiple painless nodules occur on exposed areas within 1 week to 3 months following the bite.

These enlarge and ulcerate with a characteristic erythematous raised border. An overlying crust may develop. The lesions heal slowly over months or years, sometimes leaving a disfiguring scar.

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis can often be made clinically in a patient who has been in an endemic area.Giemsa stain on a split-skin smear will demonstrate leishmania parasites in 80% of cases.

Biopsy tissue from the edge of the lesion can be examined histologically, and parasites identified by PCR; culture is less often successful.

The leishmanin skin test is positive in over 90% of cases, but does not distinguish between active and resolved infection.

Serology is unhelpful.

Small lesions usually require no treatment.

Large lesions or those in cosmetically sensitive sites can sometimes be treated locally, by curettage, cryotherapy or topical antiparasitic agents.

In other cases, systemic treatment (as for visceral leishmaniasis) is required, although treatment is less successful as antimonials are poorly concentrated in the skin;

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis occurs in 3-10% of infections with L. b. braziliensis, and is commonest in Bolivia and Peru. The cutaneous sores are followed months or years later by indurated or ulcerating lesions affecting mucosa or cartilage, typically on the lips or nose ('espundia').

Diagnosis and treatment

Biopsies usually show only very scanty organisms, although parasites can be detected by PCR;serological tests are frequently positive. Amphotericin B is the treatment of choice if available,

although systemic antimonial compounds are widely used;

miltefosine may also be effective.

Relapses are common following treatment. Patients may die because of secondary bacterial infection, or occasionally laryngeal obstruction.