Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

Lecture 2 – The Morphology & Fine

structure of bacteria

The main characteristics that distinguish

prokaryotes from eukaryotes are the

following:

1) Eukaryotic cells are generally more complex than

prokaryotic cells.

2) DNA is enclosed in a nuclear membrane and is associated

with histones and other proteins only in eukaryotes.

3) Organelles are membrane-bound in eukaryotes.

4) Prokaryotes divide by binary fission whereas eukaryotes

divide by mitosis.

5) Some structures are absent in prokaryotes: for example,

Golgi complex, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and

chloroplasts.

There are more other differences between prokaryotes

and eukaryotes you can find them in reference text books.

The Morphology of Bacteria

Bacteria differ from other single-cell microorganisms in

both their cell structure and size, which varies from 0.3–5

µm. Magnifications of 500–1000X—close to the

resolution limits of light microscopy—are required to

obtain useful images of bacteria. Another problem is that

the structures of objects the size of bacteria offers little

visual contrast. Techniques like phase contrast and dark

field microscopy, both of which allow for live cell

observation, are used to overcome this difficulty.

Chemical-staining techniques are also used, but the

prepared specimens are dead. Bacteria have three basic

forms: cocci, straight rods, and curved or spiral rods.

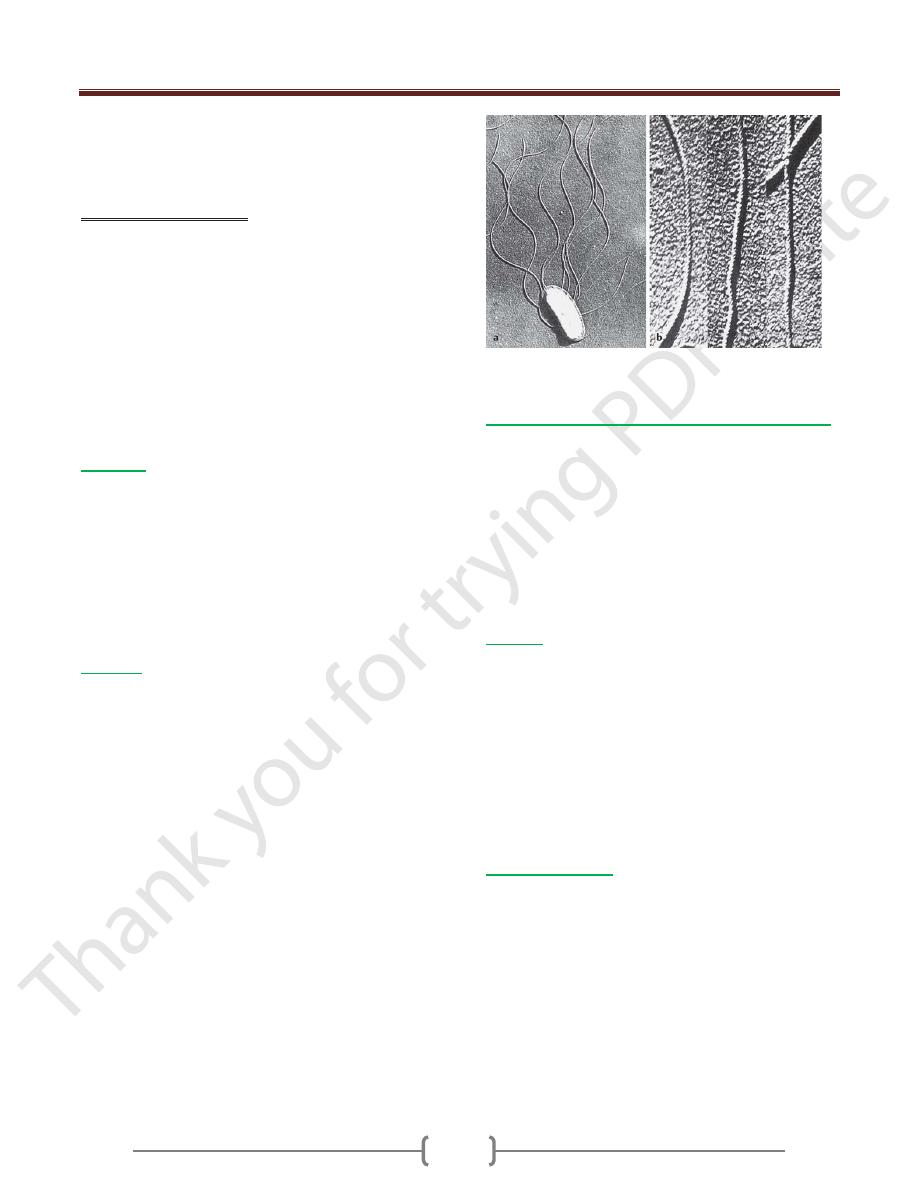

Cocci are spherical bacteria. Those found in grapelike

clusters as in this picture are staphylococci (Scanning

electron microscopy (SEM)).

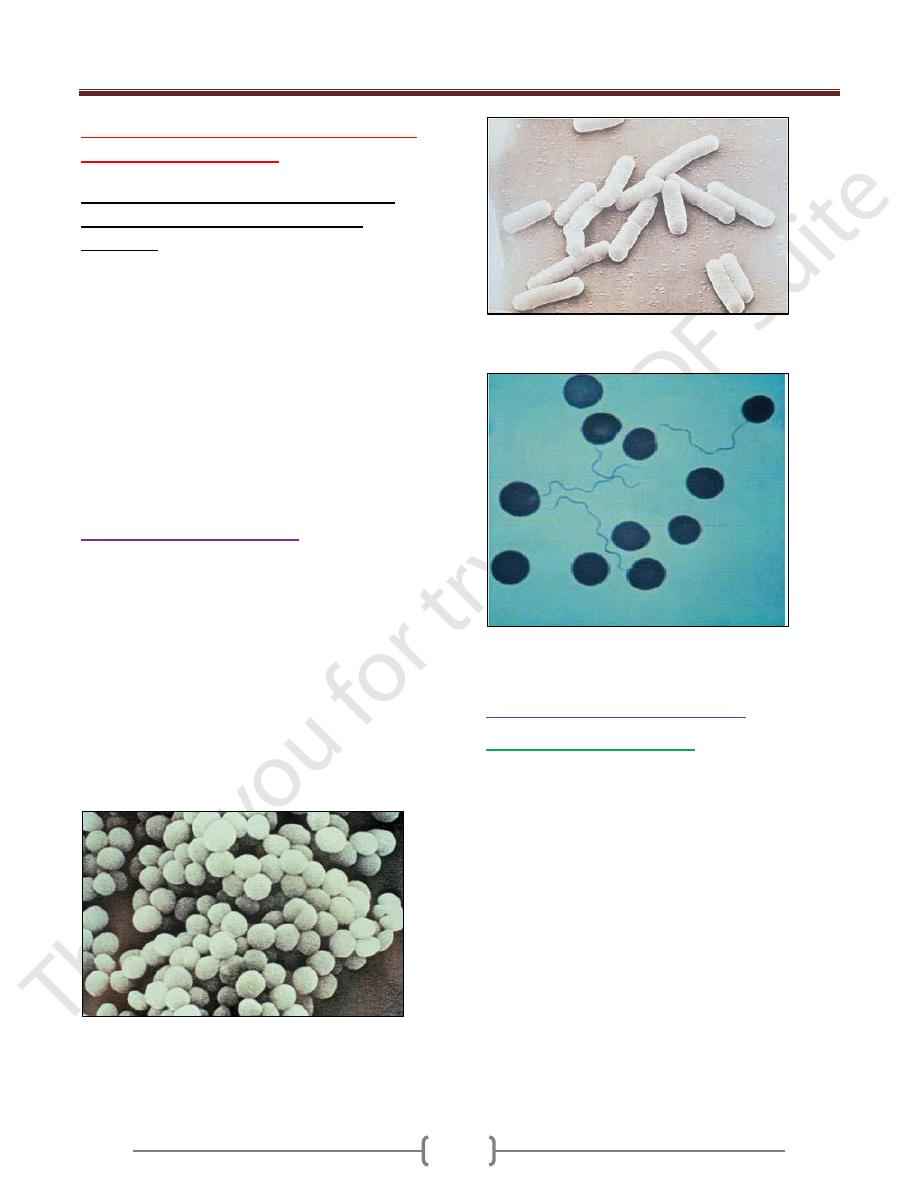

The straight rod bacteria with rounded ends

Shown here are coli bacteria (SEM).

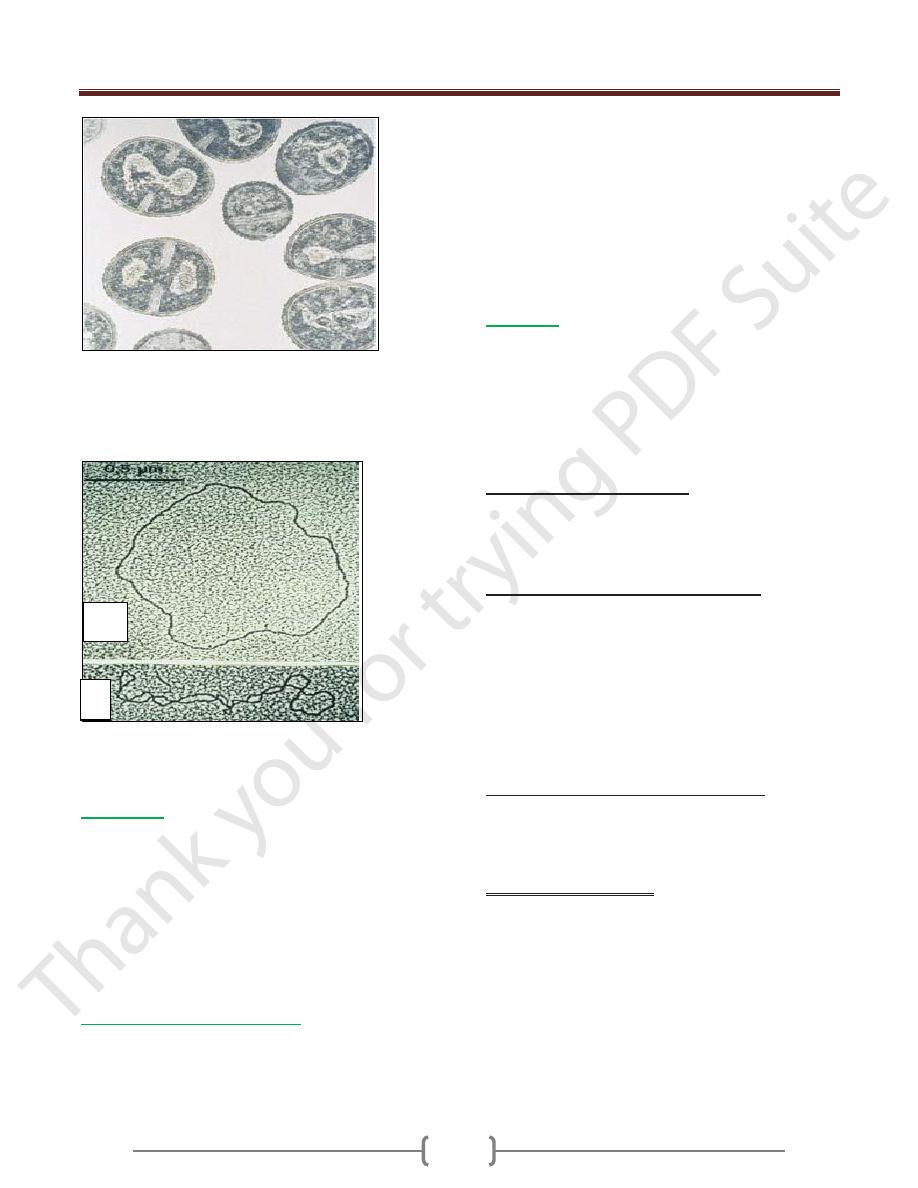

Spirilla, in this case borrelia are spiral

bacteria (light microscopy (LM), Giemsa stain).

The Structures of Bacterial cell

The Nucleoid and plasmids

The prokaryote

Nucleoid ( the equivalent of the

eukaryotic Nucleus)

consists of a very thin, long,

circular DNA molecular double strand that is not

surrounded by a membrane and localized in the

cytoplasm. In E. coli (and probably in all bacteria), it

takes the form of a single circular molecule of DNA. The

genome of E. coli comprises 4.63 X106 base pairs (bp)

that code for 4288 different proteins. The genomic

sequence of many bacteria is known. The plasmids are

nonessential genetic structures. These circular, twisted

DNA molecules are 100–1000X smaller than the nucleoid

genome structure and reproduce autonomously .The

plasmids of human pathogen bacteria often bear important

genes determining the phenotype of their cells (resistance

genes, virulence genes).

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

The nucleoid (nucleus equivalent) of bacteria consists of a

tangled circular DNA molecule without a nuclear

membrane.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of

staphylococci

A) Open circular form (OC). The result of a rupture in

one of the two nucleic acid strands. B) Twisted (CCC =

covalently closed circular), native form (TEM image).

Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm contains a large number of solute (low-

and high-molecularweight) substances, RNA and

ribosomes (approximately 20 000 per cell). Bacteria have

70S ribosomes comprising 30S and 50S subunits.

Bacterial ribosomes function as the organelles for protein

synthesis. The cytoplasm is also frequently used to store

reserve substances (glycogen depots, polymerized

metaphosphates, lipids).

The Cytoplasmic Membrane

This elementary membrane, also known as the plasma

membrane, is

a 40–80 A ˚-thick semipermeable

membrane

. It is basically a double layer of phospholipids

with numerous proteins integrated into its structure. The

most important of these membrane proteins are

permeases, enzymes for the biosynthesis of the cellwall,

transfer proteins for secretion of extracellular proteins,

sensor or signal proteins, and respiratory chain enzymes.

In electron microscopic images of Gram-positive bacteria,

the mesosomes appear as structures bound to the

membrane. How they function and what role they play

remain to be clarified.

Cell Wall

The tasks of the complex bacterial cellwall are to protect

the protoplasts from external noxae, to withstand and

maintain the osmotic pressure gradient between the cell

interior and the extracellular environment (with internal

pressures as high as 500–2000 kPa), to give the cell its

outer form and to facilitate communication with its

surroundings.

Peptidoglycan (syn. murein).

The most important

structural element of the wall is peptidoglycan, a netlike

polymer material surrounding the entire cell (sacculus). It

is made up of polysaccharide chains crosslinked by

peptides.

The cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria

. The

murein sacculus may consist of as many as 40 layers (15–

80 nm thick) and account for as much as 30% of the dry

mass of the cell wall. The membrane lipoteichoic acids

are anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane, whereas the

cell wall teichoic acids are covalently coupled to the

murein. The physiological role of the teichoic acids is not

known in detail; possibly they regulate the activity of the

autolysins that steer growth and transverse fission

processes in the cell.

The cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria

. Here, the

murein is only about 2 nm thick and contributes up to 10%

of the dry cell wall mass. The outer membrane is the salient

structural element. It contains numerous proteins (50% by

mass) as well as the medically critical lipopolysaccharide.

Outer membrane proteins

—

OmpA (outer membrane protein A) and the murein

lipoprotein form a

bond between outer membrane and murein.

—

Porins, proteins that form pores in the outer

membrane, allow passage of hydrophilic, low-molecular-

weight substances into the periplasmic space.

—

Outer membrane-associated proteins constitute

specific structures that enable bacteria to attach to host

cell receptors.

A

B

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

—

A number of Omps are transport proteins.

Examples include the LamB proteins for maltose transport

and FepA for transport of the siderophore ferric (Fe3+)

enterochelin in E. coli .

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

This molecular complex, also known as endotoxin, is

comprised of the lipoid A, the core polysaccharide, and

the O-specific polysaccharide chain.

—

Lipoid A is responsible for the toxic effect.

—

The O-specific polysaccharide chain is the so-called

O antigen.

L-forms (L = Lister Institute). The L-forms are bacteria

with murein defects, e.g., resulting from the effects of

betalactam antibiotics. L-forms are highly unstable when

subjected to osmotic influences.

Capsule

Many pathogenic bacteria make use of extracellular

enzymes to synthesize a polymer that forms a layer

around the cell: the capsule. The capsule protects bacterial

cells from phagocytosis. The capsule of most bacteria

consists of a polysaccharide. The bacteria of a single

species can be classified in different capsular serovars (or

serotypes) based on the fine chemical structure of this

polysaccharide.

Flagella

Flagella give bacteria the ability to move about actively.

The flagella (singular flagellum) are made up of a class of

linear proteins called flagellins. Flagellated bacteria

display various flagellar arrangements ranging from

monotrichous (polar flagellum; e.g., Vibrio coma),

lophotrichous (bundle of flagella at one end of the cell;

e.g., Spirillum volutans), to peritrichous (several flagella

distributed around the cell; e.g., Escherichia coli)

.

Together with the O antigens, they are used to classify

bacteria in serovars.

a

Flagellated bacterial cell (SEM, 13 000!). b Helical

structure of bacterial flagella (SEM, 77 000X).

Attachment Pili (Fimbriae), Conjugation Pili

Many Gram-negative bacteria possess thin microfibrils

made of proteins (0.1–1.5 nm thick, 4–8 nm long), the

attachment pili. They are anchored in the outer membrane

of the cell wall and extend radially from the surface.

Using these structures, bacteria are capable of specific

attachment to host cell receptors (ligand—receptor, key—

keyhole). The conjugation pili (syn. sex pili) in Gram-

negative bacteria are required for the process of

conjugation and thus for transfer of conjugative plasmids.

Biofilm

A bacterial biofilm is a structured community of bacterial

cells embedded in a self-produced polymer matrix and

attached to either an inert surface or living tissue. Such

films can develop considerable thickness (mm) . Foreign

body infections are caused by bacteria that form a biofilm

on inert surfaces. The bacteria located deep within such a

biofilm structure are effectively isolated from immune

system cells, antibodies, and antibiotics. The polymers

they secrete are frequently glycosides, from which the

term glycocalyx (glycoside cup) for the matrix is derived.

Bacterial Spores

Bacterial spores (endospores) are purely dormant life

forms. Their development from bacterial cells in a

“vegetative” state does not involve assimilation of

additional external nutrients. They are spherical to oval in

shape and are characterized by a thick spore wall & a high

level of resistance to chemical & physical noxae. Among

human pathogen bacteria, only the genera Clostridium

and Bacillus produce spores. The heat resistance of these

spores is their most important quality from a medical

point of view, since heat sterilization procedures require

very high temperatures to kill them effectively.