Unit 2: Bacteriology

88

Lecture 4 - Aerobic Spore-Former

Bacteria (Bacillus)

Bacillus anthracis

Introduction

The anthrax bacillus, Bacillus anthracis, was the first

bacterium shown to be the cause of a disease. In

1877, Robert Koch grew the organism in pure culture,

demonstrated its ability to form endospores, and

produced experimental anthrax by injecting it into

animals. Anthrax occurs primarily in animals, especially

herbivores. The pathogens are ingested with feed and

cause a severe clinical sepsis that is often lethal.

Morphology and culturing

Bacillus anthrac is very large, Gram-positive,

sporeforming rod, 1 - 1.2µm in width x 3 - 5µm in length,

with a capsule made of a glutamic acid polypeptide. The

bacterium can be cultivated in ordinary nutrient medium

under aerobic (or anaerobic) conditions. Genotypically

and phenotypically it is very similar to Bacillus

cereus, which is found in soil habitats around the world,

and to Bacillus thuringiensis, the pathogen for larvae

of Lepidoptera. The three species have the same cellular

size and morphology and form oval spores located

centrally in a nonswollen sporangium.The bacterium is

readily grown in an aerobic milieu.

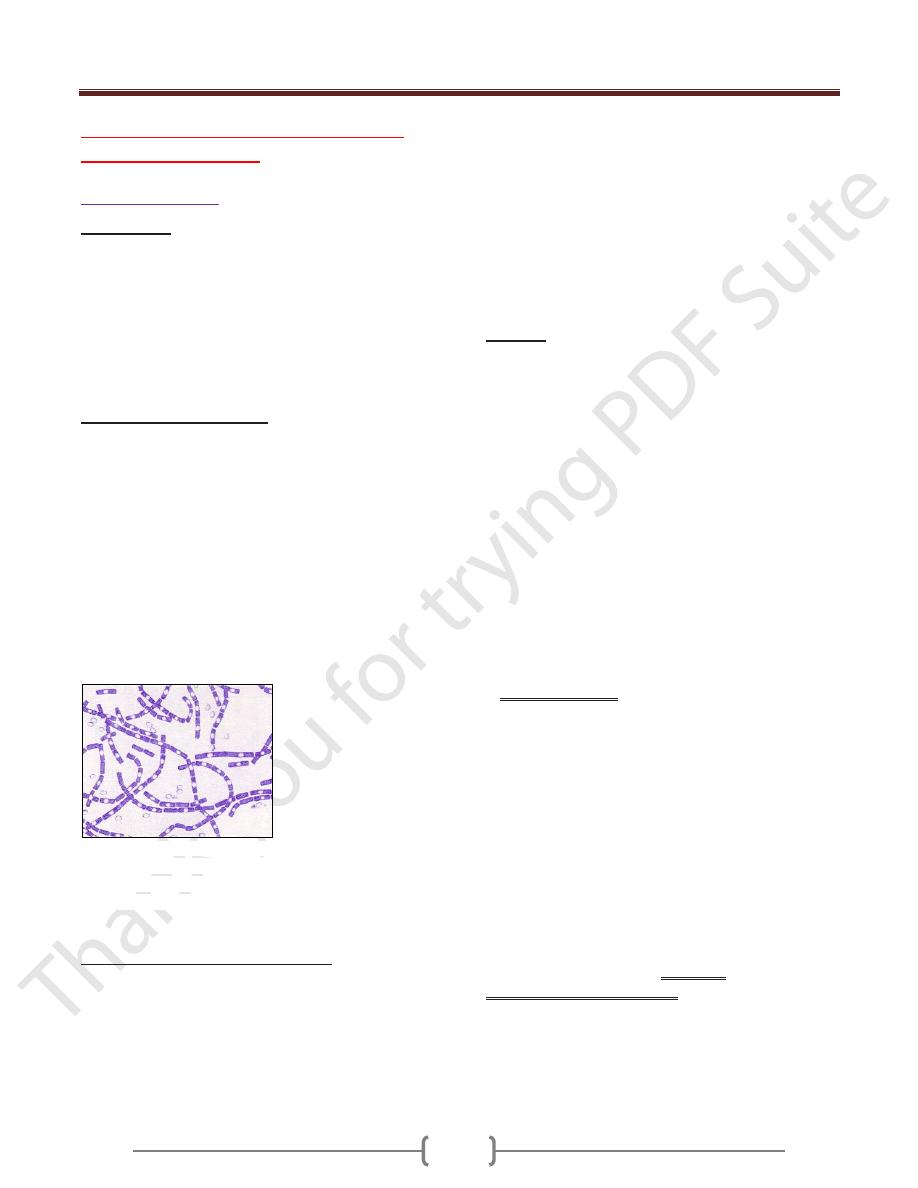

Bacillus anthracis. Gram stain. 1500X. The cells have

characteristic squared ends. The endospores are ellipsoidal

shaped and located centrally in the sporangium. The spores

are highly refractile to light and resistant to staining.

Pathogenesis and clinical picture

The pathogenicity of B. anthracis results from its

antiphagocytic capsule as well as from a toxin that causes

edemas and tissue necrosis. Human infections are

contracted from diseased animals or contaminated animal

products. Anthrax is recognized as an occupational

disease. Dermal, primary inhalational, and intestinal

anthrax are differentiated based on the pathogen’s portal

of entry. In dermal anthrax, which accounts for 90–95%

of human B. anthracis infections) the pathogens enter

through injuries in the skin. A local infection focus

similar to a carbuncle develops within two to three days.

A sepsis with a foudroyant (highly acute) course may then

develop from this primary focus. Inhalational anthrax

(bioterrorist anthrax), with its unfavorable prognosis,

results from inhalation of dust containing the pathogen.

Ingestion of contaminated foods can result in intestinal

anthrax with vomiting and bloody diarrheas.

Anthrax

Anthrax is primarily a disease of domesticated and wild

animals, particularly herbivorous animals, such as cattle,

sheep, horses, mules and goats. Humans become infected

incidentally when brought into contact with diseased

animals, which includes their flesh, bones, hides, hair and

excrement. The natural history of Bacillus anthracis is

obscure. Although the spores have been found naturally in

soil samples from around the world, the organisms cannot

be regularly cultivated from soils where there is an

absence of endemic anthrax. In the United States, the

incidence of naturally-acquired anthrax is extremely rare

(1-2 cases of cutaneous disease per year). Worldwide, the

incidence is unknown, although B. anthracis is present in

most of the world. Unreliable reporting makes it difficult

to estimate the true incidence of human anthrax

worldwide.

The most common form of the disease in humans

is cutaneous anthrax, which is usually acquired via

injured skin or mucous membranes. A minor scratch or

abrasion, usually on an exposed area of the face or neck

or arms, is inoculated by spores from the soil or a

contaminated animal or carcass.The spores germinate,

vegetative cells multiply, and a characteristic gelatinous

edema develops at the site. This develops into

papule within 12-36 hours after infection. The papule

changes rapidly to a vesicle, then a pustule (malignant

pustule), and finally into a necrotic ulcer from which

infection may disseminate, giving rise to septicemia.

Lymphatic swelling also occurs within seven days. In

severe cases, where the blood stream is eventually

invaded, the disease is frequently fatal.

Another form of the disease, inhalation

anthrax (woolsorters' disease), results most commonly

from inhalation of spore-containing dust where animal

hair or hides are being handled. The disease begins

abruptly with high fever and chest pain. It progresses

rapidly to a systemic hemorrhagic pathology and is often

Unit 2: Bacteriology

89

fatal if treatment cannot stop the invasive aspect of the

infection.

Gastrointestinal anthrax is analogous to cutaneous

anthrax but occurs on the intestinal mucosa. As in

cutaneous anthrax, the organisms probably invade the

mucosa through a preexisting lesion. The bacteria spread

from the mucosal lesion to the lymphatic system.

Intestinal anthrax results from the ingestion of

poorly cooked meat from infected animals.

Gastrointestinal anthrax is rare but may occur as

explosive outbreaks associated with ingestion of infected

animals. Intestinal anthrax has an extremely high

mortality rate.

Meningitis due to B. anthracis is a very rare complication

that may result from a primary infection elsewhere.

Pathogenicity of Bacillus anthracis

Bacillus anthracis clearly owes its pathogenicity to two

major-determinants of virulence: the formation of a poly-

D-glutamyl capsule, which mediates the invasive stage

of the infection, and the production of the

multicomponent anthrax toxin which mediates the

toxigenic stage.

Bacillus anthracis forms a single

antigenic type of capsule consisting of a poly-D-

glutamate polypeptide. All virulent strains of B.

anthracis form this capsule.

The poly-D-glutamyl capsule

is itself nontoxic, but functions to protect the organism

against complement and the bactericidal components of

serum and phagocytes, and against phagocytic engulfment

and destruction. Production of capsular material is

associated with the formation of a characteristic mucoid

or "smooth" colony type. "Smooth" (S) to "rough" (R)

colonial variants occur, which is correlated with ability to

produce the capsule. R variants are relatively avirulent

.

One component of the anthrax toxin has a lethal mode

of the action . Death is apparently due to oxygen

depletion, secondary shock, increased vascular

permeability, respiratory failure and cardiac failure. Death

from anthrax in humans or animals frequently occurs

suddenly and unexpectedly. The level of the lethal toxin

in the circulation increases rapidly quite late in the

disease, and it closely parallels the concentration of

organisms in the blood.

Production of the anthrax toxin is mediated by a

temperature-sensitive plasmid, pX01, of 110

megadaltons. The toxin consists of three distinct antigenic

components. Each component of the toxin is a

thermolabile protein with a mw of approximately 80kDa.

I. Factor I is the edema factor (EF) which is necessary for

the edema producing activity of the toxin. EF is known to

be an inherent adenylate cyclase, similar to

the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin.

II. Factor II is the protective antigen (PA), because it

induces protective antitoxic antibodies in guinea pigs. PA

is the binding (B) domain of the anthrax toxin which has

two active (A) domains, EF (above) and LF (below).

III. Factor III is known as the lethal factor (LF) because it

is essential for the lethal effects of the anthrax toxin.

Apart from their antigenicity, each of the three factors

exhibits no significant biological activity in an animal.

However, combinations of two or three of the toxin

components yield the following results in experimental

animals.

PA+LF combine to produce lethal activity

EF+PA produce edema

EF+LF is inactive

PA+LF+EF produces edema and necrosis and is lethal

Diagnosis.

The diagnostic procedure involves detection of the

pathogen in dermal lesions, sputum, and/or blood

cultures using microscopic and culturing methods.

Several nonselective and selective media for the detection

and isolation of Bacillus anthracis have been described,

as well as a rapid screening test for the bacterium based

on the morphology of microcolonies . The capsular

material can be detected by the McFadyean reaction

which involves staining with polychrome methylene

blue. Blue rods in a background of purple/pink-stained

capsular material is a positive test. Neither B.

cereus nor B. thuringiensis synthesizes this capsular

polymer, so the detection of capsular material can be used

to distinguish B. anthracis from its closest relatives .The

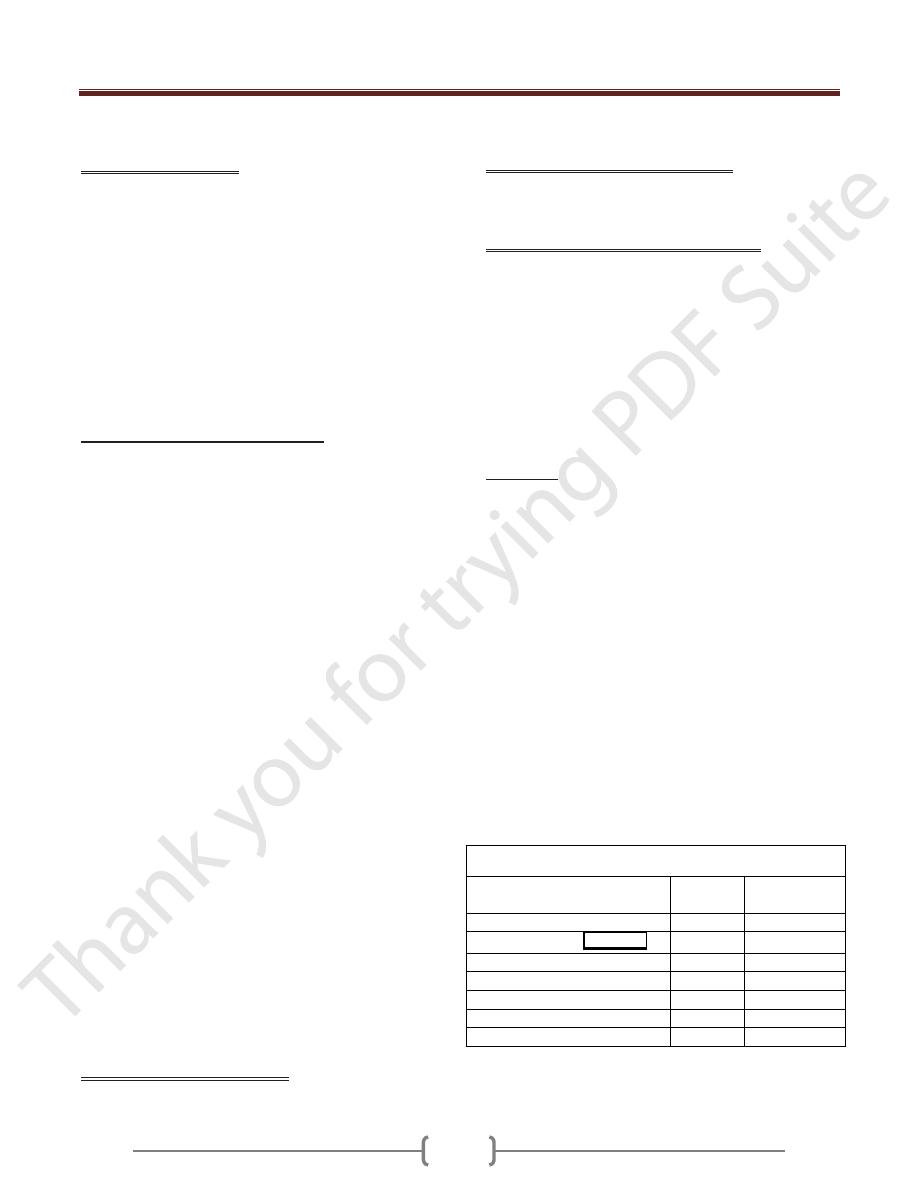

Table-1 bellow provides the differential characteristics

that are used to distinguish Bacillus anthracis from most

strains of Bacillus

The Table-1 show Differential Characteristics of B. anthracis

B. cereus and B. thuringiensis

Characteristic

B.

anthracis

B.cereus & B.

thuringiensis

growth requirement for thiamin

+

-

hemolysis on sheep blood agar

-

+

glutamyl-polypeptide capsule

+

-

lysis by gamma phage

+

-

Motility

-

+

growth on chloral hydrate agar

-

+

string-of-pearls test

+

-

Unit 2: Bacteriology

90

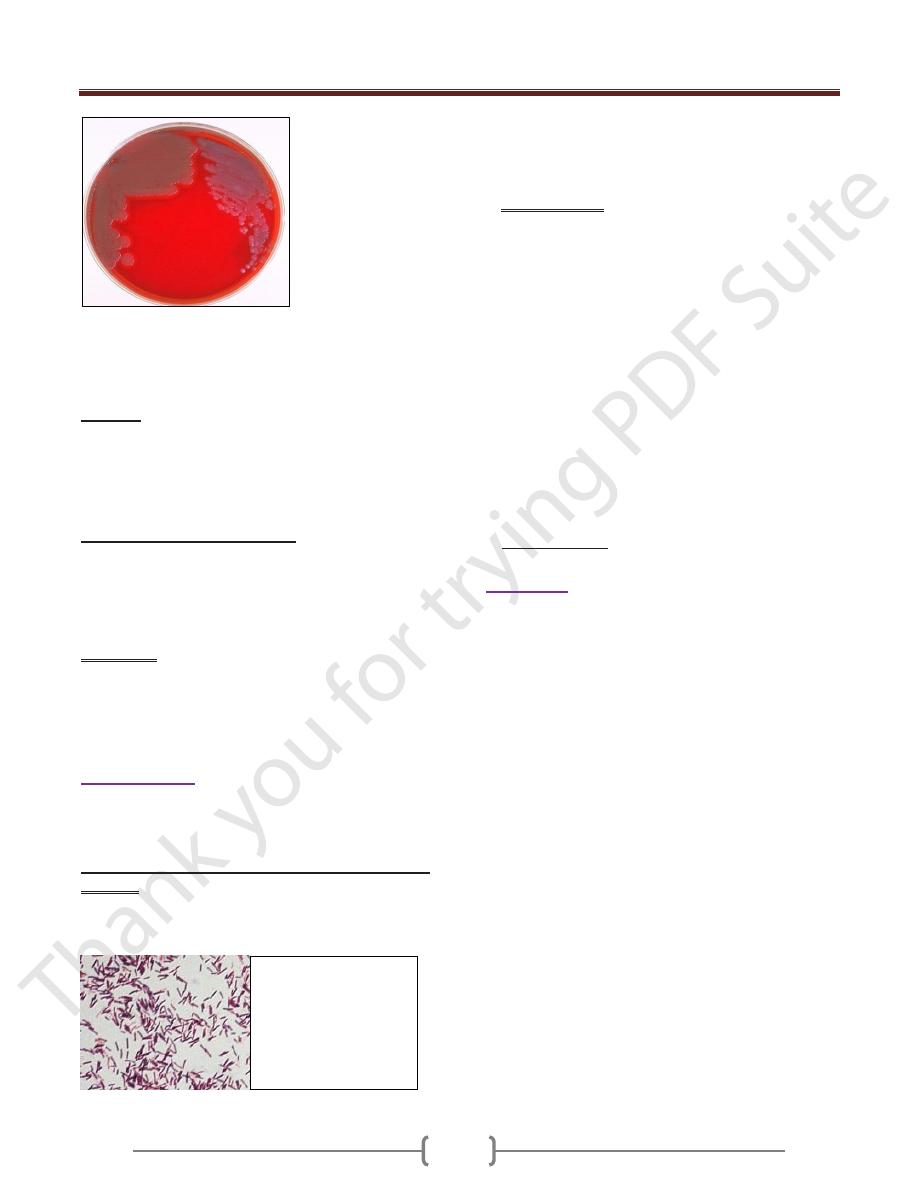

Figure 1. Colonies of Bacillus cereus on the left; colonies

of Bacillus anthracis on the right. B. cereus colonies are

larger, more mucoid, and this strain exhibits a slight zone of

hemolysis on blood agar.

Therapy

The antimicrobial agent of choice is penicillin G.

Doxycycline (a tetracycline) or ciprofloxacin (a

fluoroquinolone) are possible alternatives. Surgery is

contraindicated in cases of dermal anthrax.

Epidemiology and prophylaxis

Anthrax occurs mainly in southern Europe and South

America, where economic damage due to farm animal

infections is considerable. Humans catch the disease from

infected animals or contaminated animal products.

Anthrax is a classic zoonosis.

Prophylaxis involves mainly exposure prevention

measures such as avoiding contact with diseased animals

and disinfection of contaminated products. A cell-free

vaccine obtained from a culture filtrate can be used for

vaccine prophylaxis in high-risk persons.

Bacillus cereus

Bacillus cereus has been recognized as an agent of food

poisoning since 1955. It is not a reportable disease, and

usually goes undiagnosed.

B. cereus causes two types of food-borne illnesses.

One type is characterized by nausea and vomiting and

abdominal cramps and has an incubation period of 1 to 6

hours. It resembles Staphylococcus aureus

(staph) food poisoning in its symptoms and incubation

period. This is the "short-incubation" or emetic form of

the disease.

The second type is manifested primarily by abdominal

cramps and diarrhea following an incubation period of 8

to 16 hours. Diarrhea may be a small volume or profuse

and watery. This type is referred to as the "long-

incubation" or diarrheal form of the disease, and it

resembles food poisoning caused by Clostridium

perfringens. In either type, the illness usually lasts less

than 24 hours after onset. In a few patients symptoms

may last longer. The short-incubation form is caused by a

preformed, heat-stable emetic toxin, ETE. The

mechanism and site of action of this toxin are unknown,

although the small molecule forms ion channels and holes

in membranes. The long-incubation form of illness is

mediated by the heat-labile diarrheagenic enterotoxin

Nhe and/or hemolytic enterotoxin HBL, which cause

intestinal fluid secretion, probably by several

mechanisms, including pore formation and activation

of adenylate cyclase enzymes.

Summary:

The natural habitat of Bacillus anthracis, a Gram-positive,

sporing, obligate aerobic rod bacterium, is the soil. The

organism causes anthrax infections in animals. Human

infections result from contact with sick animals or animal

products contaminated with the spores. Infections are

classified according to the portal of entry as dermal

anthrax (95% of cases), primary inhalational anthrax, and

intestinal anthrax. Sepsis can develop from the primary

infection focus. Laboratory diagnosis includes

microscopic and cultural detection of the pathogen in

relevant materials and blood cultures. The therapeutic

agent of choice is penicillin G. The genera Bacillus and

Clostridium belong to the Bacillaceae family of sporing

bacteria. There are numerous species in the genus Bacillus

(e.g., B. cereus, B. subtilis, etc.) that normally live in the

soil. The organism in the group that is of veterinary and

human medical interest is Bacillus anthracis.

Bacillus cereus. Gram

stain. 450X. Bacilli are

large bacteria, so that

they are readily

observed with the

microscope's "high dry

objective".