Basic Anatomy

69

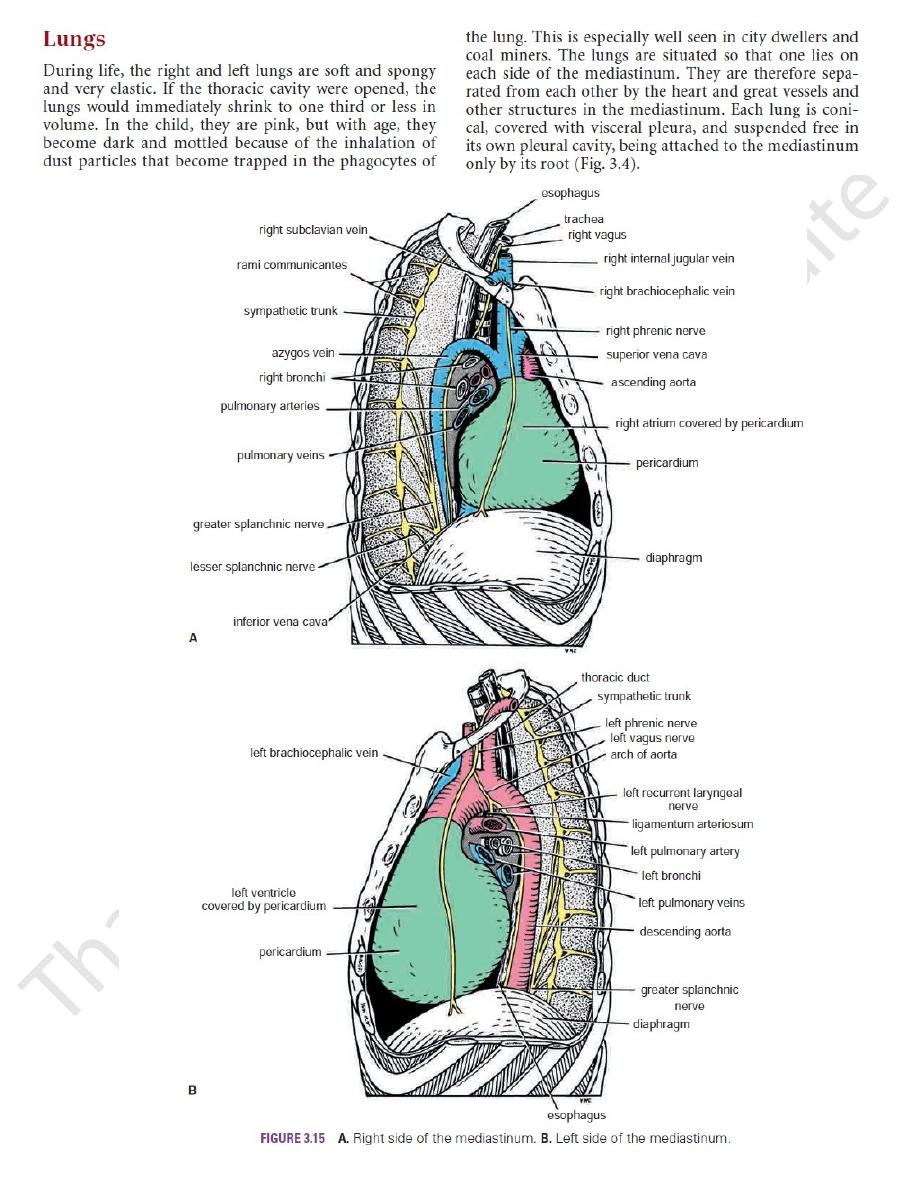

sympathetic trunk

cut rib

cut costal

cartilage

cut costal cartilage

azygos vein

intercostal nerve

right bronchi

pulmonary veins

greater splanchnic

nerve

inferior vena cava

right subclavian vein

right clavicle

right subclavius

muscle

internal thoracic

artery

superior vena cava

ascending aorta

right phrenic

nerve

right atrium

right ventricle

right cupola of

diaphragm

ANTERIOR

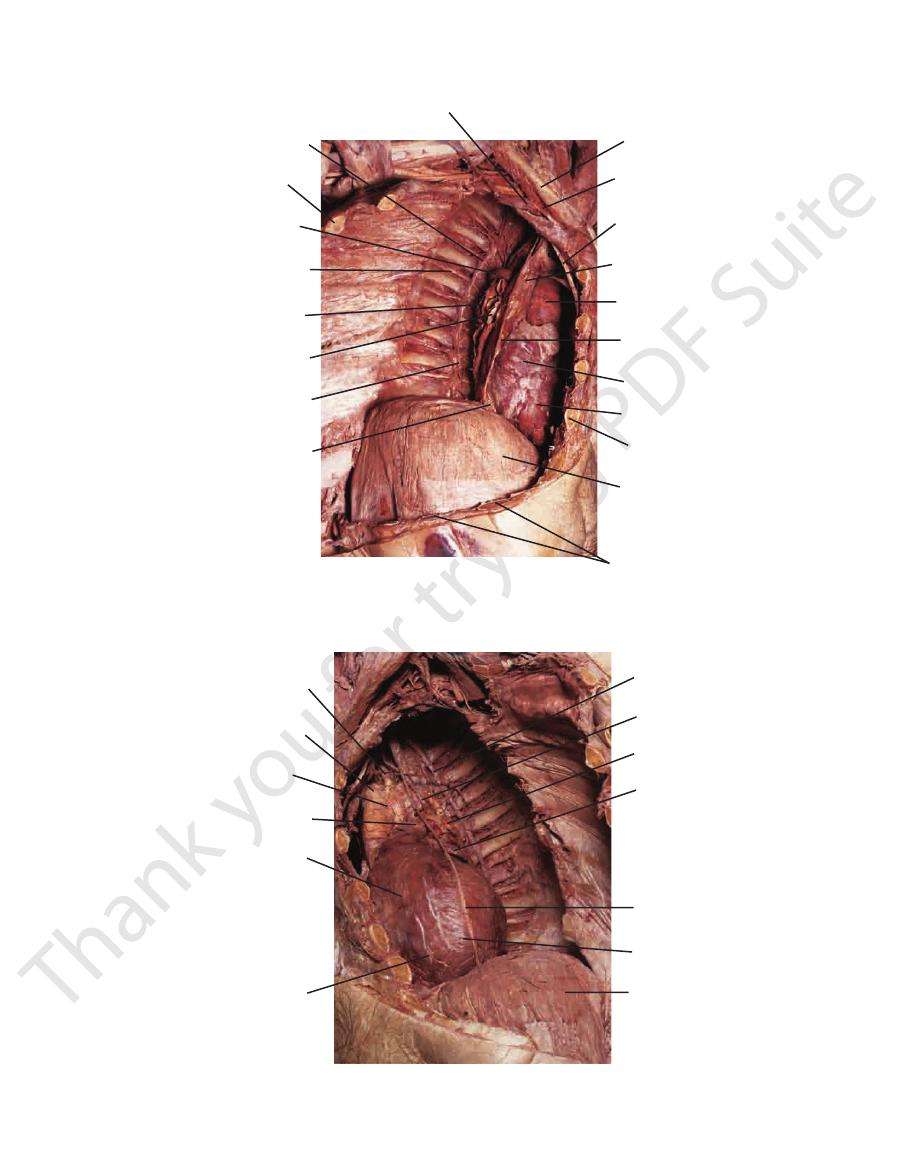

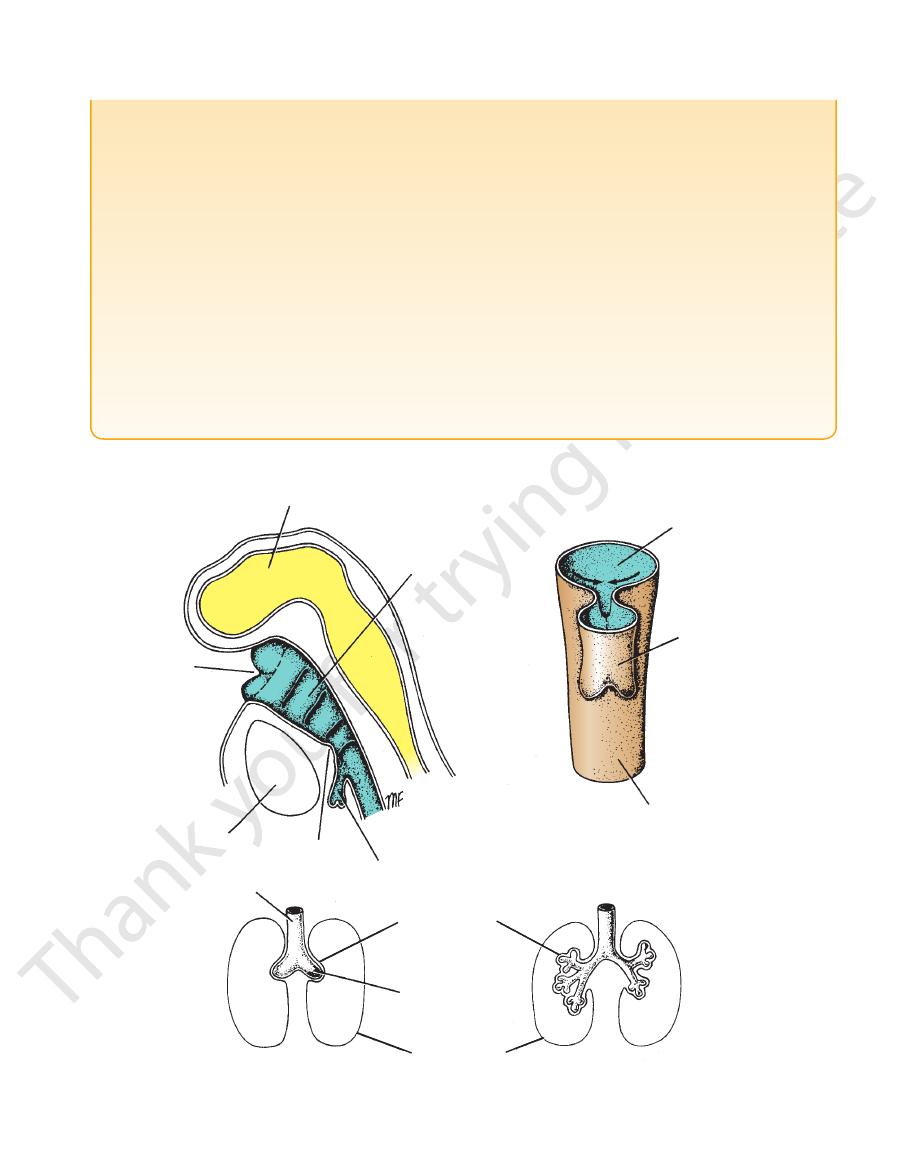

FIGURE 3.16

ed. The

Dissection of the right side of the mediastinum; the right lung and the pericardium have been remov

costal parietal pleura has also been removed.

left subclavian

artery

left common

carotid artery

arch of

aorta

pulmonary trunk

right ventricle

apex of heart

sympathetic

trunk

left vagus

nerve

descending

aorta

left auricle

left phrenic

nerve

left cupola of

diaphragm

left ventricle

ANTERIOR

FIGURE 3.17

e been removed. The costal

Dissection of the left side of the mediastinum; the left lung and the pericardium hav

parietal pleura has also been removed.

70

CHAPTER 3

The Thorax: Part II—The Thoracic Cavity

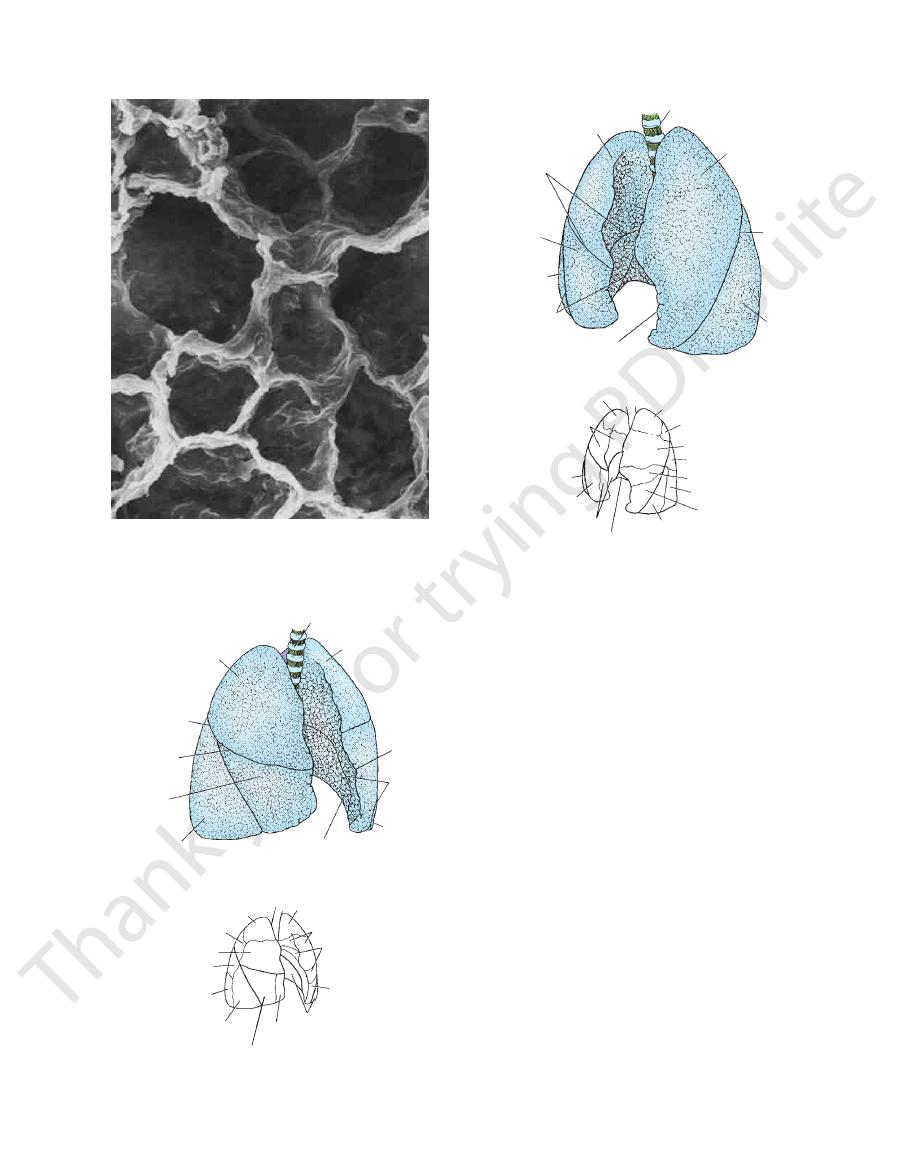

respiratory bronchiole

trachea

left principal bronchus

lobar bronchus

segmental bronchus

alveolar duct

alveolar sac

alveolus

terminal bronchiole

FIGURE 3.18

Trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli. Note the path taken by inspired air from

is found. The

cardiac notch

here on the left lung that the

is thin and overlaps the heart; it is

anterior border

The

enter and leave the lung.

root

form the

depression in which the bronchi, vessels, and nerves that

hilum,

3.21). At about the middle of this surface is the

cardium and other mediastinal structures (Figs. 3.20 and

which is molded to the peri

mediastinal surface,

concave

which corresponds to the concave chest wall; and a

face,

costal sur

that sits on the diaphragm; a convex

cave

the neck for about 1 in. (2.5 cm) above the clavicle; a con

which projects upward into

apex,

Each lung has a blunt

the trachea to the alveoli.

-

base

-

-

a

posterior border is thick and lies beside the vertebral column.

oblique fissure in the midaxillary line. The middle lobe is

surface at the level of the 4th costal cartilage to meet the

runs horizontally across the costal

horizontal fissure

The

posterior border about 2.5 in. (6.25 cm) below the apex.

ward across the medial and costal surfaces until it cuts the

runs from the inferior border upward and back

fissure

oblique

(Fig. 3.20). The

lower lobes

upper, middle,

by the oblique and horizontal fissures into three lobes: the

The right lung is slightly larger than the left and is divided

Lobes and Fissures

Right Lung

and

-

Basic Anatomy

71

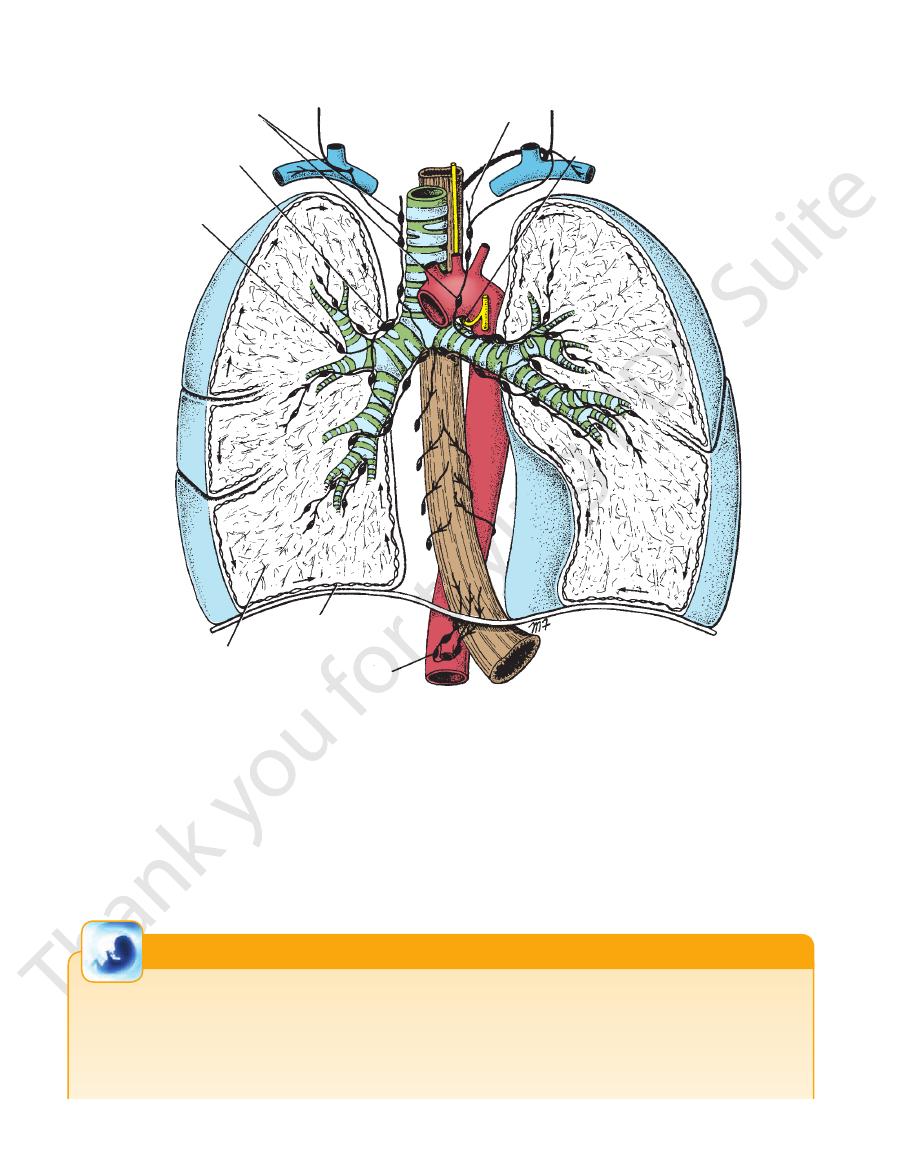

trachea

upper lobe of right lung

right principal

bronchus

upper lobe of left lung

left principal

bronchus

lower lobe

of left lung

lower lobe of right lung

bronchi in middle lobe of right lung

(dissected)

FIGURE 3.19

A plastinized specimen of an adult trachea,

of the trachea than the left main bronchus.

right main bronchus is wider and a more direct continuation

been dissected to reveal the larger bronchi. Note that the

principal bronchi, and lung; some of the lung tissue has

apex

upper lobe

horizontal fissure

middle

lobe

oblique fissure

base

lower

lobe

apex

lower lobe

middle

lobe

upper lobe

FIGURE 3.20

Lateral and medial surfaces of the right lung.

the blood within the surrounding capillaries.

the air in the alveolar lumen through the alveolar wall into

of blood capillaries. Gaseous exchange takes place between

and 3.23). Each alveolus is surrounded by a rich network

of several alveoli opening into a single chamber (Figs. 3.22

The alveolar sacs consist

alveolar sacs.

pouchings called

lead into tubular passages with numerous thin-walled out

which

alveolar ducts,

bronchioles end by branching into

a respiratory bronchiole is about 0.5 mm. The respiratory

The diameter of

respiratory bronchiole.

explains the name

air takes place in the walls of these outpouchings, which

ings from their walls. Gaseous exchange between blood and

(Fig. 3.22), which show delicate outpouch

bronchioles

terminal

The bronchioles then divide and give rise to

circularly arranged smooth muscle fibers.

epithelium. The submucosa possesses a complete layer of

cartilage in their walls and are lined with columnar ciliated

are <1 mm in diameter (Fig. 3.22). Bronchioles possess no

which

bronchioles,

smallest bronchi divide and give rise to

cartilage, which become smaller and fewer in number. The

in the trachea are gradually replaced by irregular plates of

chi become smaller, the U-shaped bars of cartilage found

mental bronchus divides repeatedly (Fig. 3.22). As the bron

On entering a bronchopulmonary segment, each seg

nerve supply.

Each segment has its own lymphatic vessels and autonomic

tive tissue between adjacent bronchopulmonary segments.

the tributaries of the pulmonary veins run in the connec

accompanied by a branch of the pulmonary artery, but

connective tissue (Fig. 3.22). The segmental bronchus is

which is surrounded by

bronchopulmonary segment,

functionally independent unit of a lung lobe called a

Each segmental bronchus passes to a structurally and

(Fig. 3.18).

segmental (tertiary) bronchi

branches called

ary) bronchus, which passes to a lobe of the lung, gives off

tional, and surgical units of the lungs. Each lobar (second

The bronchopulmonary segments are the anatomic, func

horizontal fissure in the left lung.

(Fig. 3.21). There is no

lower lobes

and

upper

lobes: the

The left lung is divided by a similar oblique fissure into two

Left Lung

oblique fissures.

thus a small triangular lobe bounded by the horizontal and

Bronchopulmonary Segments

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

apex

apex

upper lobe

lower lobe

base

oblique

fissure

lower lobe

upper lobe

FIGURE 3.21

Lateral and medial surfaces of the left lung.

72

CHAPTER 3

The Thorax: Part II—The Thoracic Cavity

autonomic nerves

lymphatic vessel

pulmonary vein

terminal bronchiole

respiratory

bonchiole

alveolar sac

bronchopulmonary segment

segmental bronchus

alveolus

lung lobule

pulmonary artery

pulmonary vein in

intersegmental

connective tissue

FIGURE 3.22

A bronchopulmonary segment and a lung lobule. Note that the pulmonary veins lie within the connective tissue

The main characteristics of a bronchopulmonary

septa that separate adjacent segments.

segment may be summarized as follows:

3.15, 3.16, and 3.17).

pleura to the visceral pleura covering the lungs (Figs. 3.5,

sheath of pleura, which joins the mediastinal parietal

vessels, and nerves. The root is surrounded by a tubular

chi, pulmonary artery and veins, lymph vessels, bronchial

entering or leaving the lung. It is made up of the bron

is formed of structures that are

root of the lung

The

pulmonary medicine or surgery.

to memorize the details unless one intends to specialize in

nary segments is of clinical importance, it is unnecessary

Although the general arrangement of the bronchopulmo

basal, lateral basal, posterior basal

Superior (apical), medial basal, anterior

Inferior lobe:

gular, inferior lingular

Apical, posterior, anterior, superior lin

Superior lobe:

Left lung

basal, lateral basal, posterior basal

Superior (apical), medial basal, anterior

Inferior lobe:

Lateral, medial

Middle lobe:

Apical, posterior, anterior

Superior lobe:

Right lung

3.25) are as follows:

The main bronchopulmonary segments (Figs. 3.24 and

removed surgically.

Because it is a structural unit, a diseased segment can be

adjacent bronchopulmonary segments.

The segmental vein lies in the connective tissue between

vessels, and autonomic nerves.

It has a segmental bronchus, a segmental artery, lymph

It is surrounded by connective tissue.

root.

It is pyramid shaped, with its apex toward the lung

It is a subdivision of a lung lobe.

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

-

-

-

Basic Anatomy

73

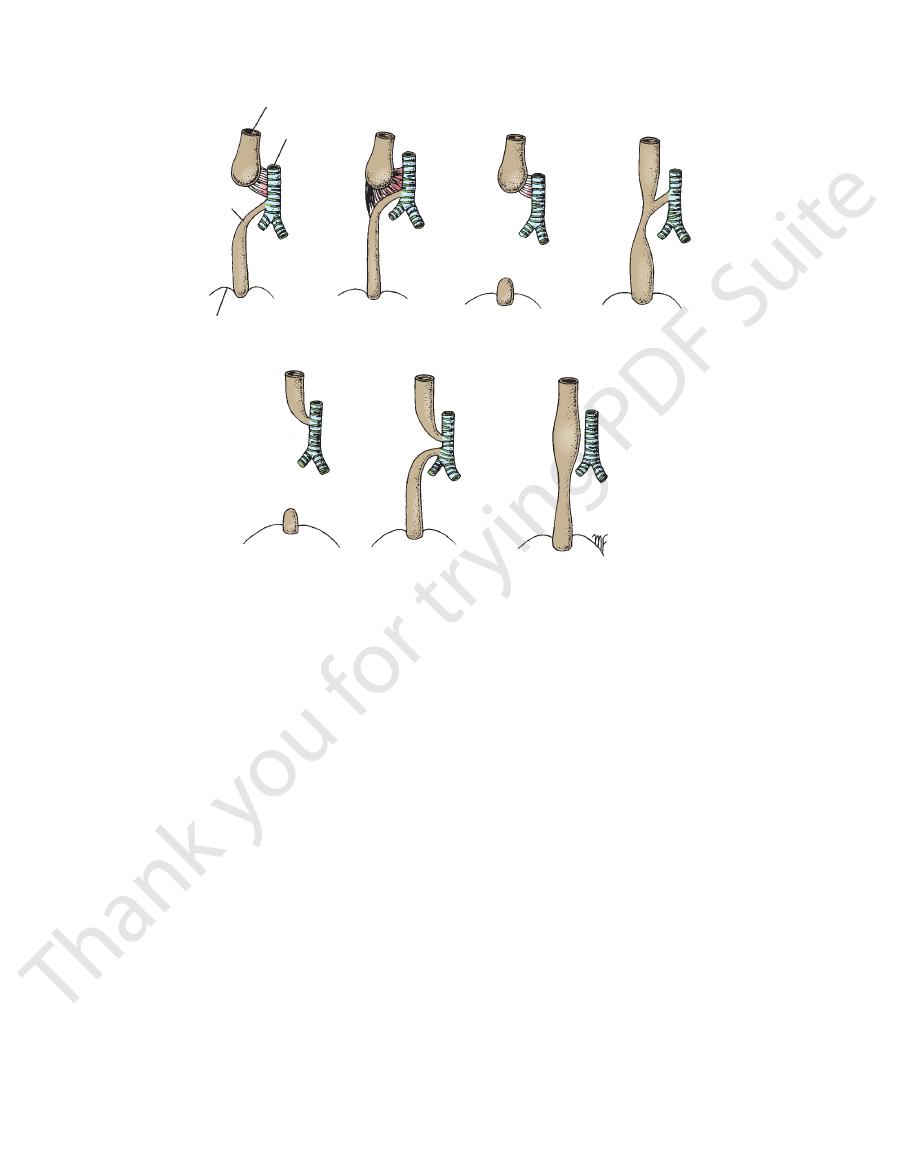

FIGURE 3.23

Scanning electron micrograph of the lung

tesy of Dr. M. Koering.)

sions, or alcoves, along the walls of the alveolar sac. (Cour

showing numerous alveolar sacs. The alveoli are the depres-

-

upper lobe of

right lung

oblique

fissure

horizontal

fissure

middle lobe

of right lung

lower lobe

of right lung

lower lobe

of left lung

lower lobe

of left lung

oblique

fissure

cardiac

notch

upper lobe

of left lung

trachea

lateral

division

of middle

medial

division

of middle

anterior basal

inferior division

of lingular

superior division

of lingular

anterior

apical

apical

posterior

anterior

apical lower

lateral basal

anterior basal

B

A

FIGURE 3.24

Lungs viewed from the right.

Bronchopulmonary segments.

Lobes.

A.

B.

upper lobe

of right lung

horizontal

fissure

middle lobe

of right lung

lower lobe

of right lung

oblique

fissure

cardiac

notch

lower lobe

of left lung

oblique

fissure

upper lobe

of left lung

trachea

apical

medial division

of middle

posterior

basal

anterior

basal

inferior division of lingular

lateral basal

superior division of lingular

apical lower

anterior

posterior

apical

A

B

lateral division

of middle

anterior

anterior

basal

FIGURE 3.25

Lungs viewed from the left.

bronchomediastinal lymph trunks.

then into the

and

tracheobronchial nodes

the hilum and drains into the

in the hilum of the lung. All the lymph from the lung leaves

stance; the lymph then enters the bronchopulmonary nodes

located within the lung sub

pulmonary nodes

ing through

and pulmonary vessels toward the hilum of the lung, pass

travels along the bronchi

deep plexus

The

monary nodes.

bronchopul

the hilum, where the lymph vessels enter the

ceral pleura and drains over the surface of the lung toward

lies beneath the vis

superficial (subpleural) plexus

The

uses (Fig. 3.26); they are not present in the alveolar walls.

The lymph vessels originate in superficial and deep plex

Lymph Drainage of the Lungs

into the left atrium of the heart.

pulmonary veins leave each lung root (Fig. 3.15) to empty

mental connective tissue septa to the lung root. Two

taries of the pulmonary veins, which follow the interseg

blood leaving the alveolar capillaries drains into the tribu

nal branches of the pulmonary arteries. The oxygenated

The alveoli receive deoxygenated blood from the termi

veins) drain into the azygos and hemiazygos veins.

bronchial veins (which communicate with the pulmonary

arteries, which are branches of the descending aorta. The

ceral pleura receive their blood supply from the bronchial

The bronchi, the connective tissue of the lung, and the vis

chopulmonary segments.

Lobes.

A.

B. Bron-

Blood Supply of the Lungs

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

74

CHAPTER 3

The Thorax: Part II—The Thoracic Cavity

tracheobronchial nodes

bronchopulmonary nodes

pulmonary nodes

deep lymphatic plexus

superficial lymphatic plexus

celiac nodes

left recurrent laryngeal nerve

bronchomediastinal trunk

FIGURE 3.26

Lymph drainage of the lung and lower end of the esophagus.

and decrease of the capacity of the thoracic cavity. The rate

ration—which are accomplished by the alternate increase

Respiration consists of two phases—inspiration and expi

parasympathetic nerves.

pass to the central nervous system in both sympathetic and

membrane and from stretch receptors in the alveolar walls

Afferent impulses derived from the bronchial mucous

increased glandular secretion.

fibers produce bronchoconstriction, vasodilatation, and

tion and vasoconstriction. The parasympathetic efferent

The sympathetic efferent fibers produce bronchodilata

receives parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve.

is formed from branches of the sympathetic trunk and

of efferent and afferent autonomic nerve fibers. The plexus

composed

pulmonary plexus

At the root of each lung is a

Nerve Supply of the Lungs

-

The Mechanics of Respiration

-

Development of the Lungs and Pleura

the permanent opening into the larynx. The laryngotracheal tube

and the epithelium of the alveoli develop from this groove. The

A longitudinal groove develops in the entodermal lining of the

floor of the pharynx. This groove is known as the laryngotra-

cheal groove. The lining of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi

margins of the groove fuse and form the laryngotracheal tube

(Fig. 3.27). The fusion process starts distally so that the lumen

becomes separated from the developing esophagus. Just behind

the developing tongue, a small opening persists that will become

grows caudally into the splanchnic mesoderm and will eventually

lie anterior to the esophagus. The tube divides distally into the

(continued)

E M B R Y O L O G I C N O T E S

Basic Anatomy

75

right and left

ferent types of atresia, with and without fistula, are shown in

formed from somatic mesoderm. By the seventh month, the

derived

visceral pleura

Each lung will receive a covering of

ects into the pleural part of the embryonic coelom (Fig. 3.27). The

surrounding the tube, and the upper part of the tube becomes

lung buds. Cartilage develops in the mesenchyme

the larynx, whereas the lower part becomes the trachea.

Each lung bud consists of an entodermal tube surrounded

by splanchnic mesoderm; from this, all the tissues of the corre-

sponding lung are derived. Each bud grows laterally and proj-

lung bud divides into three lobes and then into two, correspond-

ing to the number of main bronchi and lobes found in the fully

developed lung. Each main bronchus then divides repeatedly in

a dichotomous manner, until eventually the terminal bronchioles

and alveoli are formed. The division of the terminal bronchioles,

with the formation of additional bronchioles and alveoli, contin-

ues for some time after birth.

from the splanchnic mesoderm. The parietal pleura will be

capillary loops connected with the pulmonary circulation have

become sufficiently well developed to support life, should pre-

mature birth take place. With the onset of respiration at birth, the

lungs expand and the alveoli become dilated. However, it is only

after 3 or 4 days of postnatal life that the alveoli in the periphery

of each lung become fully expanded.

Congenital Anomalies

Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula

If the margins of the laryngotracheal groove fail to fuse ade-

quately, an abnormal opening may be left between the laryn-

gotracheal tube and the esophagus. If the tracheoesophageal

septum formed by the fusion of the margins of the laryngo-

tracheal groove should be deviated posteriorly, the lumen of

the esophagus would be much reduced in diameter. The dif-

Figure 3.28. Obstruction of the esophagus prevents the child from

early diagnosis, it is often possible to correct this serious anom

larynx and trachea, which usually results in pneumonia. With

swallowing saliva and milk, and this leads to aspiration into the

-

aly surgically.

brain

pharynx

mouth

pericardial cavity

copula

laryngotracheal tube

pharynx

laryngotracheal tube

esophagus

trachea

visceral pleura

lung bud

parietal pleura

A

B

C

D

FIGURE 3.27

The development of the lungs.

The lung buds divide to form the main bronchi.

The lung buds invaginate the wall of the intraembryonic

the laryngotracheal groove fuse to form the laryngotracheal tube.

The margins of

The laryngotracheal groove and tube have been formed.

A.

B.

C.

coelom. D.

76

CHAPTER 3

The Thorax: Part II—The Thoracic Cavity

esophagus

trachea

fistula

diaphragm

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

FIGURE 3.28

Different types of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula.

nal viscera and the tone of the muscles of the anterior

the effect of the descent of the diaphragm on the abdomi

An additional factor that must not be overlooked is

(Fig. 3.10).

the other ribs to it by contracting the intercostal muscles

this can be accomplished by fixing the 1st rib and raising

thoracic cavity will be increased. As described previously,

raised (like bucket handles), the transverse diameter of the

dles (see Fig. 3.29). It therefore follows that if the ribs are

as forward around the chest wall, they resemble bucket han

vertebral column. Because the ribs curve downward as well

the sternum via their costal cartilages and behind with the

The ribs articulate in front with

Transverse Diameter

the first rib.

means, all the ribs are drawn together and raised toward

contracting the intercostal muscles (Fig. 3.10). By this

by the contraction of the scaleni muscles of the neck and

(Fig. 3.29). This can be brought about by fixing the 1st rib

the lower end of the sternum would be thrust forward

diameter of the thoracic cavity would be increased and

ribs were raised at their sternal ends, the anteroposterior

If the downward-sloping

Anteroposterior Diameter

diaphragm is lowered (Fig. 3.29).

contracts, the domes become flattened and the level of the

is formed by the mobile diaphragm. When the diaphragm

suprapleural membrane and is fixed. Conversely, the floor

raised and the floor lowered. The roof is formed by the

Theoretically, the roof could be

Vertical Diameter

and how they may be increased (Fig. 3.29).

Consider now the three diameters of the thoracic cavity

sure entering the box through the tube.

diameters, and this results in air under atmospheric pres

capacity of the box can be increased by elongating all its

(Fig. 3.29). The

trachea

at the top, which is a tube called the

Compare the thoracic cavity to a box with a single entrance

Inspiration

patients and is faster in children and slower in the elderly.

varies between 16 and 20 per minute in normal resting

cases, the lower esophageal segment communicates with the trachea, and types A and B occur more commonly.

Narrowing of the esophagus without a fistula. In most

Separate esophagotracheal and tracheoesophageal fistulas.

An esophagotracheal fistula; the esophagus is not connected with the distal end, which is rudimentary.

A tracheoesophageal fistula with narrowing of

Complete blockage of the esophagus; the distal end is rudimentary.

Similar to type A, but the two parts of the esophagus are joined together by fibrous tis

with a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Complete blockage of the esophagus

A.

B.

-

sue. C.

D.

the esophagus. E.

F.

G.

Quiet Inspiration

-

-

-

abdominal wall. As the diaphragm descends on inspiration,

the diaphragm will now have its central tendon supported

further diaphragmatic descent. On further contraction,

other upper abdominal viscera act as a platform that resists

further abdominal relaxation is possible, and the liver and

nal wall musculature. However, a point is reached when no

accommodated by the reciprocal relaxation of the abdomi

intra-abdominal pressure rises. This rise in pressure is

-

Basic Anatomy

77

expanding thoracic cavity

bucket handle action

lateral expansion

descent of diaphragm

anteroposterior expansion

expanding box

FIGURE 3.29

The different ways in which the capacity of the

supported by grasping a chair back or table, the sternal

lis minor to pull up the ribs. If the upper limbs can be

muscles, enabling the serratus anterior and the pectora

are fixed by the trapezius, levator scapulae, and rhomboid

already engaged becomes more violent, and the scapulae

toid. In respiratory distress, the action of all the muscles

scalenus anterior and medius and the sternocleidomas

can raise the ribs is brought into action, including the

capacity of the thoracic cavity occurs. Every muscle that

In deep forced inspiration, a maximum increase in the

Forced Inspiration

serratus posterior superior muscles.

muscles

levatores costarum

assist in elevating the ribs, namely, the

less important muscles also contract on inspiration and

Apart from the diaphragm and the intercostals, other

intercostal muscles in raising the lower ribs (Fig. 3.10).

from below, and its shortening muscle fibers will assist the

thoracic cavity is increased during inspiration.

and the

-

-

origin of the

oralis major muscles can also assist the

pect

abdominal form.

racic and abdominal forms of respiration, but mainly the

The male uses both the tho

thoracic type of respiration.

the diaphragm on inspiration. This is referred to as the

the movements of the ribs rather than on the descent of

piratory movements. The female tends to rely mainly on

In the adult, a sexual difference exists in the type of res

oblique, and the adult form of respiration is established.

After the second year of life, the ribs become more

abdominal type of respiration.

is easily seen, respiration at this age is referred to as the

outward excursion of the anterior abdominal wall, which

tion. Because this is accompanied by a marked inward and

diaphragm to increase their thoracic capacity on inspira

tal. Thus, babies have to rely mainly on the descent of the

In babies and young children, the ribs are nearly horizon

Types of Respiration

a higher level.

size. The lower margins of the lungs shrink and rise to

and the costodiaphragmatic recess becomes reduced in

matic and costal parietal pleura come into apposition,

ment of the diaphragm, increasing areas of the diaphrag

lungs become reduced in size. With the upward move

contract. The elastic tissue of the lungs recoils, and the

the bifurcation of the trachea. The bronchi shorten and

In expiration, the roots of the lungs ascend along with

minor role.

inferior and the latissimus dorsi muscles may also play a

the lowered 12th rib (Fig. 3.10). The serratus posterior

may contract, pull the ribs together, and depress them to

under these circumstances some of the intercostal muscles

tracts and pulls down the 12th rib. It is conceivable that

rior abdominal wall. The quadratus lumborum also con

the forcible contraction of the musculature of the ante

Forced expiration is an active process brought about by

Forced Expiration

ing down the lower ribs.

play a minor role in pull

ratus posterior inferior muscles

ser

wall, which forces the relaxing diaphragm upward. The

increase in tone of the muscles of the anterior abdominal

tion of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm, and an

brought about by the elastic recoil of the lungs, the relaxa

Quiet expiration is largely a passive phenomenon and is

Expiration

lower level.

the expanding sharp lower edges of the lungs descend to a

costodiaphragmatic recess of the pleural cavity opens, and

nective tissue are stretched. As the diaphragm descends, the

the lungs, the elastic tissue in the bronchial walls and con

increased capacity of the thoracic cavity. With expansion of

sure on the outer surface of the lungs brought about by the

upper part of the respiratory tract and the negative pres

of the positive atmospheric pressure exerted through the

circulation. Air is drawn into the bronchial tree as the result

alveolar capillaries dilate, thus assisting the pulmonary

as two vertebrae. The bronchi elongate and dilate and the

the bifurcation of the trachea may be lowered by as much

In inspiration, the root of the lung descends and the level of

process.

Lung Changes on Inspiration

-

-

Quiet Expiration

-

-

-

-

-

Lung Changes on Expiration

-

-

-

-

-

-

78

CHAPTER 3

The Thorax: Part II—The Thoracic Cavity

Physical Examination of the Lungs

is often quickly followed by infection. To aid in the normal drain

Excessive accumulation of bronchial secretions in a lobe or seg

and

Many diseases of the lungs, such as

ther impeded by the presence of excess mucus, which the patient

racic cage becomes permanently enlarged, forming the so-called

ficulty in expiring, although inspiration is accomplished normally.

tion, usually causing the asthmatic patient to experience great dif

spasm of the smooth muscle in the wall of the bronchioles. This

One of the problems associated with bronchial asthma is the

the lower deep cervical nodes just above the level of the clavicle.

the bronchomediastinal trunks may result in early involvement in

nerves, leading to hoarseness of the voice. Lymphatic spread via

bronchomediastinal nodes and may involve the recurrent laryngeal

lung. The neoplasm rapidly spreads to the tracheobronchial and

larger bronchi and is therefore situated close to the hilum of the

commences in most patients in the mucous membrane lining the

deaths in men and is becoming increasingly common in women. It

Bronchogenic carcinoma accounts for about one third of all cancer

benign neoplasm may require surgical removal. If it is restricted

costal cartilages are sufficiently elastic to permit considerable

retractors that allow the ribs to be widely separated are used. The

taken through an intercostal space (see page 46). Special rib

shoulder because the skin of this region is supplied by the supra

nerve endings, so that pain in the chest is always the result of

visceral pleura until it reaches the lung root. It then passes into the

the lung connective tissue. From there, the air moves under the

pneumothorax and collapse of the lung. It can also find its way into

the lung, and air can escape into the pleural cavity, causing a

cage, a splinter from a fractured rib can nevertheless penetrate

Although the lungs are well protected by the bony thoracic

For physical examination of the patient, it is helpful to remember

that the upper lobes of the lungs are most easily examined from

the front of the chest and the lower lobes from the back. In the

axillae, areas of all lobes can be examined.

Trauma to the Lungs

A physician must always remember that the apex of the lung

projects up into the neck (1 in. [2.5 cm] above the clavicle) and

can be damaged by stab or bullet wounds in this area.

mediastinum and up to the neck. Here, it may distend the subcu-

taneous tissue, a condition known as subcutaneous emphysema.

The changes in the position of the thoracic and upper abdom-

inal viscera and the level of the diaphragm during different

phases of respiration relative to the chest wall are of consider-

able clinical importance. A penetrating wound in the lower part

of the chest may or may not damage abdominal viscera, depend-

ing on the phase of respiration at the time of injury.

Pain and Lung Disease

Lung tissue and the visceral pleura are devoid of pain-sensitive

conditions affecting the surrounding structures. In tuberculosis

or pneumonia, for example, pain may never be experienced.

Once lung disease crosses the visceral pleura and the pleural

cavity to involve the parietal pleura, pain becomes a prominent

feature. Lobar pneumonia with pleurisy, for example, produces a

severe tearing pain, accentuated by inspiring deeply or cough-

ing. Because the lower part of the costal parietal pleura receives

its sensory innervation from the lower five intercostal nerves,

which also innervate the skin of the anterior abdominal wall,

pleurisy in this area commonly produces pain that is referred to

the abdomen. This has sometimes resulted in a mistaken diagno-

sis of an acute abdominal lesion.

In a similar manner, pleurisy of the central part of the dia-

phragmatic pleura, which receives sensory innervation from the

phrenic nerve (C3, 4, and 5), can lead to referred pain over the

-

clavicular nerves (C3 and 4).

Surgical Access to the Lungs

Surgical access to the lung or mediastinum is commonly under-

bending. Good exposure of the lungs is obtained by this method.

Segmental Resection of the Lung

A localized chronic lesion such as that of tuberculosis or a

to a bronchopulmonary segment, it is possible carefully to dis-

sect out a particular segment and remove it, leaving the sur-

rounding lung intact. Segmental resection requires that the

radiologist and thoracic surgeon have a sound knowledge of the

bronchopulmonary segments and that they cooperate fully to

localize the lesion accurately before operation.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

Hematogenous spread to bones and the brain commonly occurs.

Conditions That Decrease Respiratory Efficiency

Constriction of the Bronchi (Bronchial Asthma)

particularly reduces the diameter of the bronchioles during expira-

-

The lungs consequently become greatly distended and the tho-

barrel chest. In addition, the air flow through the bronchioles is fur-

is unable to clear because an effective cough cannot be produced.

Loss of Lung Elasticity

emphysema

pulmonary

fibrosis, destroy the elasticity of the lungs, and thus the lungs are

unable to recoil adequately, causing incomplete expiration. The

respiratory muscles in these patients have to assist in expiration,

which no longer is a passive phenomenon.

Loss of Lung Distensibility

Diseases such as silicosis, asbestosis, cancer, and pneumonia

interfere with the process of expanding the lung in inspiration.

A decrease in the compliance of the lungs and the chest wall

then occurs, and a greater effort has to be undertaken by the

inspiratory muscles to inflate the lungs.

Postural Drainage

-

ment of a lung can seriously interfere with the normal flow of air

into the alveoli. Furthermore, the stagnation of such secretions

-

age of a bronchial segment, a physiotherapist often alters the

position of the patient so that gravity assists in the process of

drainage. Sound knowledge of the bronchial tree is necessary to

determine the optimum position of the patient for good postural

drainage.

C L I N I C A L N O T E S

Basic Anatomy

that closely covers the heart (Fig. 3.32).

continuous with the visceral layer of serous pericardium

reflected around the roots of the great vessels to become

lines the fibrous pericardium and is

parietal layer

The

(Fig. 3.31).

coats the heart. It is divided into parietal and visceral layers

The serous pericardium lines the fibrous pericardium and

nopericardial ligaments.

ster

pericardium is attached in front to the sternum by the

cavae, and the pulmonary veins (Fig. 3.32). The fibrous

the pulmonary trunk, the superior and inferior venae

vessels passing through it (Fig. 3.31)—namely, the aorta,

diaphragm. It fuses with the outer coats of the great blood

sac. It is firmly attached below to the central tendon of the

The fibrous pericardium is the strong fibrous part of the

vertebrae.

costal cartilages and anterior to the 5th to the 8th thoracic

terior to the body of the sternum and the 2nd to the 6th

middle mediastinum (Figs. 3.2, 3.30, 3.31, and 3.32), pos

of the heart can contract. The pericardium lies within the

serve as a lubricated container in which the different parts

restrict excessive movements of the heart as a whole and to

heart and the roots of the great vessels. Its function is to

The pericardium is a fibroserous sac that encloses the

79

Pericardium

-

Fibrous Pericardium

-

Serous Pericardium

right common

carotid artery

right subclavian

artery and vein

brachiocephalic

artery

right brachiocephalic

vein

superior vena

cava

right lung

pericardium

diaphragm

left lung

left

brachiocephalic

vein

left subclavian

artery and vein

left common carotid artery

esophagus

trachea

FIGURE 3.30

The pericardium and the lungs exposed from

in front.

parietal layer of

serous pericardium

visceral layer of serous

pericardium (epicardium)

fibrous pericardium

large blood vessel

heart

pericardial cavity

FIGURE 3.31

Different layers of the pericardium.

apex, which is directed downward, forward, and to the left.

phragmatic (inferior), and a base (posterior). It also has an

The heart has three surfaces: sternocostal (anterior), dia

pericardium.

the great blood vessels but otherwise lies free within the

astinum (Figs. 3.33 and 3.34). It is connected at its base to

amid shaped and lies within the pericardium in the medi

The heart is a hollow muscular organ that is somewhat pyr

branches of the sympathetic trunks and the vagus nerves.

ceral layer of the serous pericardium is innervated by

pericardium are supplied by the phrenic nerves. The vis

The fibrous pericardium and the parietal layer of the serous

page 91). They have no clinical significance.

sequence of the way the heart bends during development

(see

large veins (Fig. 3.32). The pericardial sinuses form as a con

the aorta and pulmonary trunk and the reflection around the

that lies between the reflection of serous pericardium around

which is a short passage

transverse sinus,

of the heart is the

(Fig. 3.32). Also on the posterior surface

oblique sinus

serous pericardium around the large veins forms a recess called

On the posterior surface of the heart, the reflection of the

which acts as a lubricant to facilitate movements of the heart.

pericardial fluid,

amount of tissue fluid (about 50 mL), the

(Fig. 3.31). Normally, the cavity contains a small

cavity

pericardial

parietal and visceral layers is referred to as the

The slitlike space between the

epicardium.

often called the

is closely applied to the heart and is

visceral layer

The

Pericardial Sinuses

the

-

Nerve Supply of the Pericardium

-

Heart

-

-

Surfaces of the Heart

-