160

CHAPTER 5

between the viscera.

surfaces of the peritoneum and allows free movement

which lubricates the

peritoneal fluid,

serous fluid, the

and 5.7). The peritoneum secretes a small amount of

(Figs. 5.5

epiploic foramen

or the

ing of the lesser sac,

open

with one another through an oval window called the

ach. The greater and lesser sacs are in free communication

is smaller and lies behind the stom

lesser sac

pelvis. The

partment and extends from the diaphragm down into the

is the main com

greater sac

sac (Figs. 5.5 and 5.6). The

and the lesser

greater sac

and is divided into two parts: the

The peritoneal cavity is the largest cavity in the body

supports the kidneys.

kidneys, this tissue contains a large amount of fat, which

in the area of the

extraperitoneal tissue;

tissue called the

of the abdominal and pelvic walls is a layer of connective

Between the parietal peritoneum and the fascial lining

the uterus, and the vagina.

munication with the exterior through the uterine tubes,

males, this is a closed cavity, but in females, there is com

In

peritoneal cavity.

space of the balloon, is called the

the parietal and visceral layers, which is in effect the inside

covers the organs. The potential space between

toneum

visceral peri

the abdominal and pelvic cavities, and the

lines the walls of

parietal peritoneum

from outside. The

regarded as a balloon against which organs are pressed

the viscera (Figs. 5.5 and 5.6). The peritoneum can be

walls of the abdominal and pelvic cavities and clothes

The peritoneum is a thin serous membrane that lines the

abdominal wall.

the upper poles of the kidneys (Fig. 5.4) on the posterior

The suprarenal glands are two yellowish organs that lie on

muscle.

that runs vertically downward on the psoas

ureter

to a

the liver is smaller than the right). Each kidney gives rise

slightly higher than the right (because the left lobe of

of the vertebral column (Fig. 5.4). The left kidney lies

up on the posterior abdominal wall, one on each side

The kidneys are two reddish brown organs situated high

the 10th left rib.

and the diaphragm (Fig. 5.4). It lies along the long axis of

The Abdomen: Part II—The Abdominal Cavity

Kidneys

Suprarenal Glands

Peritoneum

General Arrangement

-

-

-

-

-

lesser sac

ileum

greater sac

inferior vena

cava

ascending colon

paracolic gutters

descending colon

aorta

mesentery

coils of ileum

greater omentum

hepatic

artery

portal vein

bile duct

free margin of

lesser omentum

inferior vena

cava

right kidney

left kidney

splenicorenal ligament

gastrosplenic

omentum (ligament)

aorta

stomach

lesser sac

greater sac

falciform ligament

liver

A

B

spleen

right

left

T12

L4

median

umbilical

ligament

lateral umbilical ligament

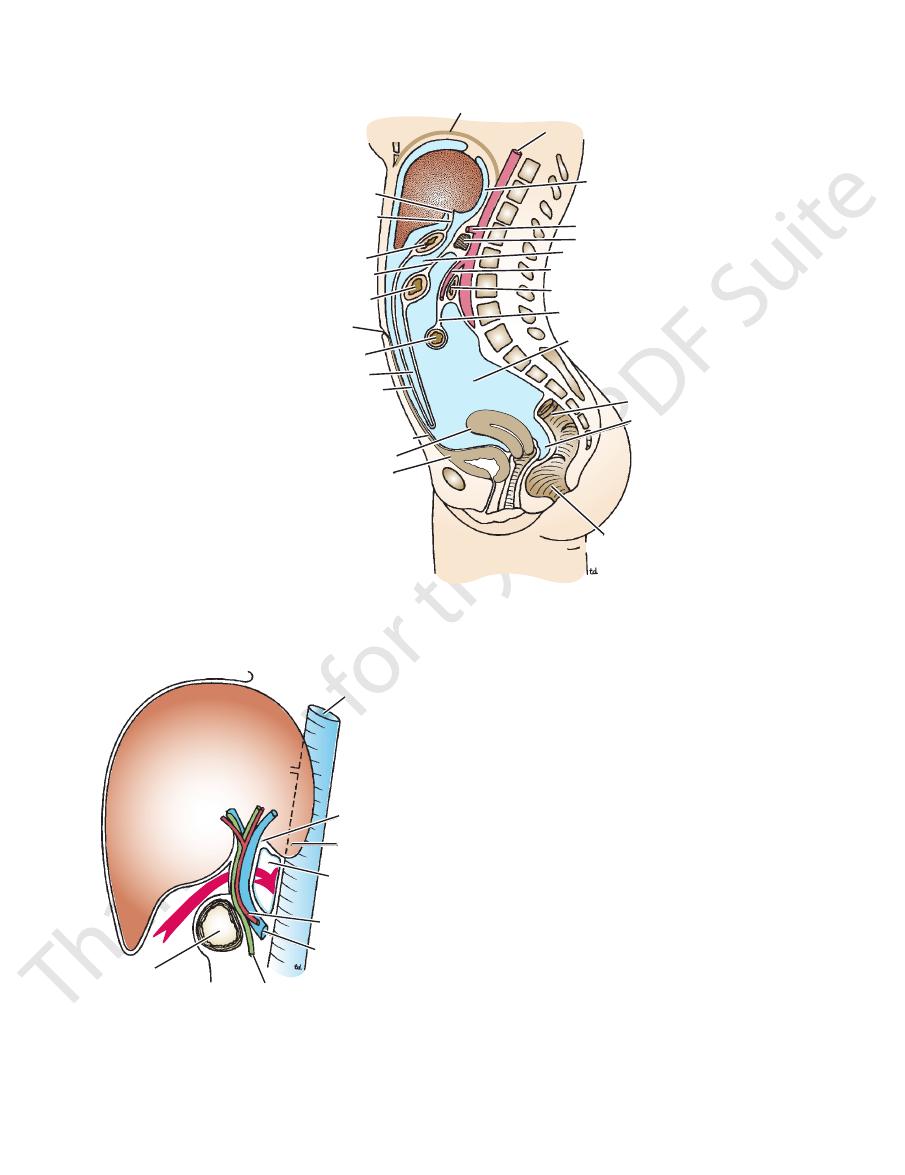

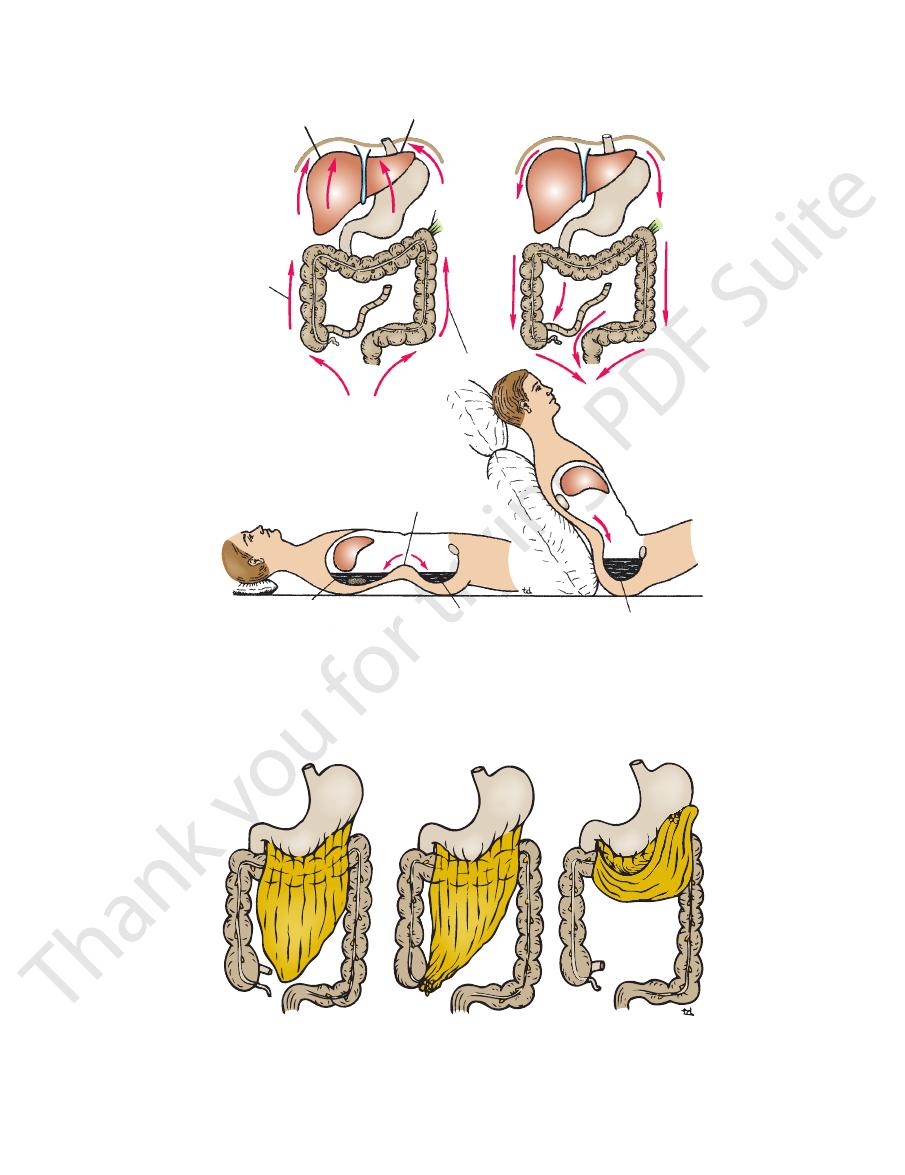

FIGURE 5.5

Transverse sections of the abdomen showing the arrangement of the peritoneum. The

position of the opening of the lesser sac. These sections are viewed from below.

arrow in B indicates the

Basic Anatomy

(Figs. 5.8 and 5.10).

left triangular ligaments

right

coronary ligament,

form ligament,

for example, is connected to the diaphragm by the

that connect solid viscera to the abdominal walls. The liver,

Peritoneal ligaments are two-layered folds of peritoneum

organs by omenta.

covered with visceral peritoneum and is attached to other

appears to be surrounded by the peritoneal cavity, but it is

neal cavity. An intraperitoneal organ, such as the stomach,

organs. No organ, however, is actually within the perito

ing parts of the colon are examples of retroperitoneal

peritoneum. The pancreas and the ascending and descend

the peritoneum and are only partially covered with visceral

intraperitoneal organs. Retroperitoneal organs lie behind

stomach, jejunum, ileum, and spleen are good examples of

it is almost totally covered with visceral peritoneum. The

neal covering. An organ is said to be intraperitoneal when

describe the relationship of various organs to their perito

are used to

retroperitoneal

intraperitoneal

The terms

161

Intraperitoneal and Retroperitoneal

Relationships

and

-

-

-

Peritoneal Ligaments

falci-

the

and the

and

diaphragm

porta hepatis

lesser omentum

stomach

transverse mesocolon

transverse colon

umbilicus

jejunum

greater omentum

median umbilical ligament

uterus

bladder

anal canal

rectouterine pouch

rectum

greater sac

mesentery

third part of duodenum

superior mesenteric artery

lesser sac

pancreas

celiac artery

aorta

superior recess

of lesser sac

inferior recess of lesser sac

FIGURE 5.6

Sagittal section of the female abdomen showing the arrangement of the peritoneum.

liver

bile duct

portal vein

hepatic artery

entrance to lesser sac

(epiploic foramen)

caudate lobe

inferior vena cava

porta hepatis

first part of

duodenum

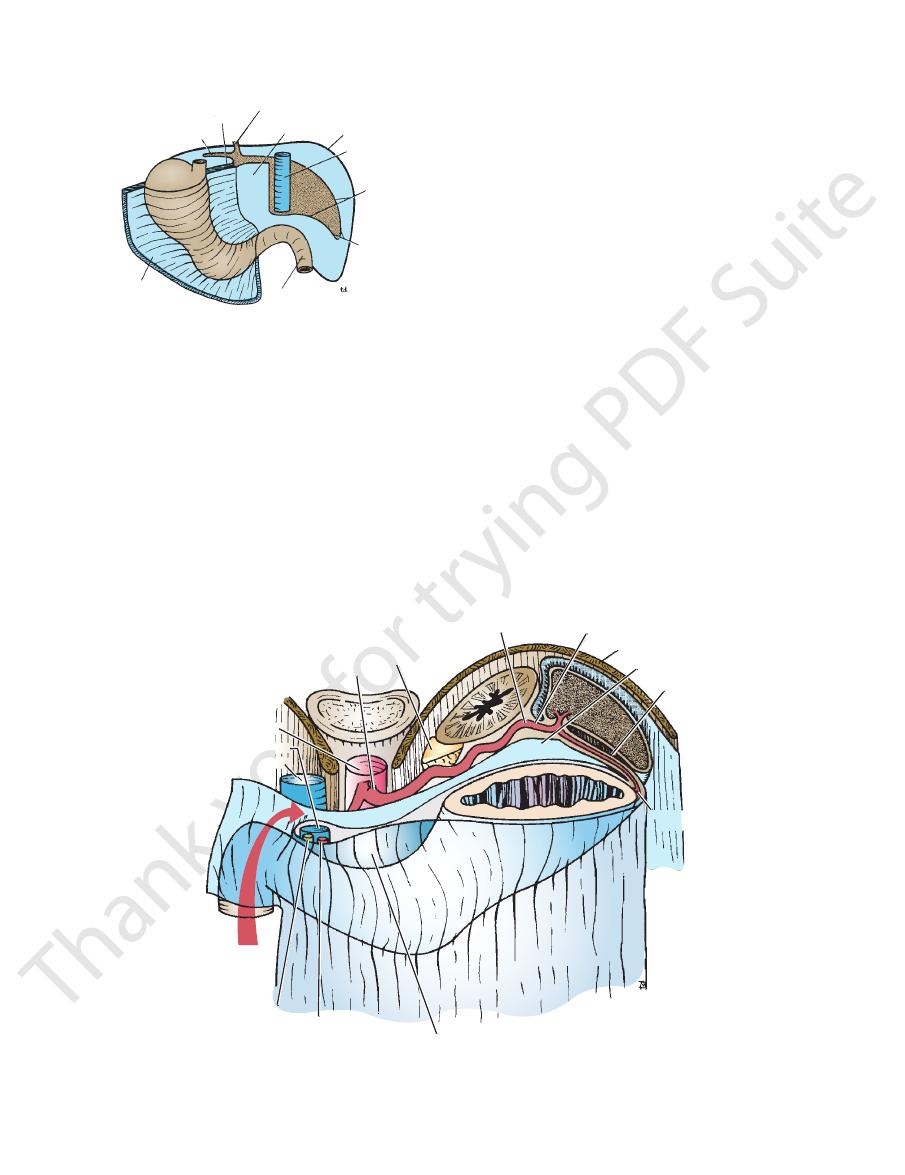

FIGURE 5.7

Sagittal section through the entrance into the

the greater sac through the epiploic foramen into the lesser

arrow

boundaries to the opening. (Note the

lesser sac showing the important structures that form

passing from

sac.)

162

CHAPTER 5

The Abdomen: Part II—The Abdominal Cavity

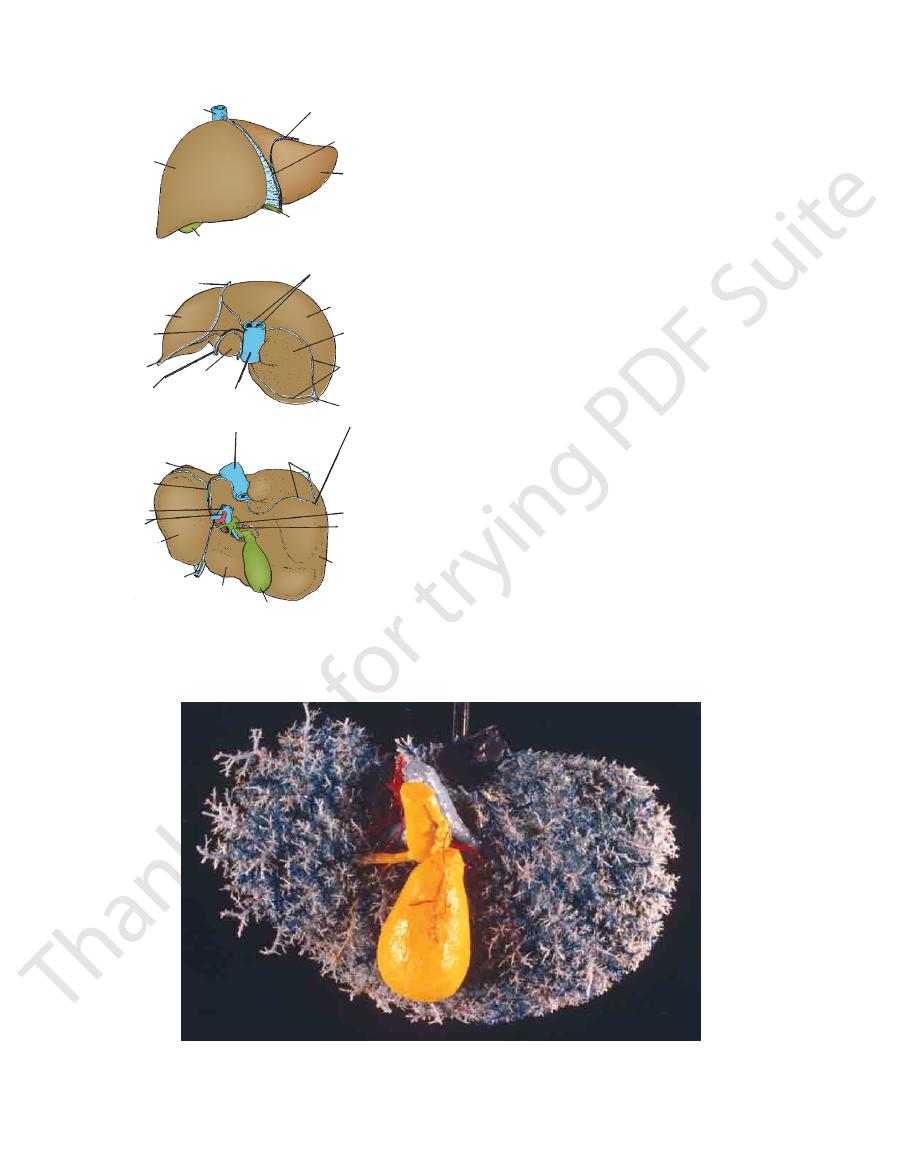

FIGURE 5.9

ace. The portal vein has been

A plastinized specimen of the liver as seen on its posteroinferior (visceral) surf

diaphragm and downward between the layers of the greater

tum (Figs. 5.5, 5.6, and 5.11). It extends upward as far as the

The lesser sac lies behind the stomach and the lesser omen

the abdomen seen in Figures 5.5 and 5.6.

should be studied in the transverse and sagittal sections of

The extent of the peritoneum and the peritoneal cavity

mit blood, lymph vessels, and nerves to reach the viscera.

The peritoneal ligaments, omenta, and mesenteries per

(Figs. 5.6 and 5.13).

sigmoid mesocolon

transverse mesocolon,

mesentery of the small intestine,

wall, for example, the

necting parts of the intestines to the posterior abdominal

Mesenteries are two-layered folds of peritoneum con

the hilum of the spleen (Fig. 5.5).

(ligament) connects the stomach to

trosplenic omentum

gas

hepatis on the undersurface of the liver (Fig. 5.6). The

from the fissure of the ligamentum venosum and the porta

suspends the lesser curvature of the stomach

omentum

lesser

to be attached to the transverse colon (Fig. 5.6). The

the coils of the small intestine and is folded back on itself

colon (Fig. 5.2). It hangs down like an apron in front of

nects the greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse

con

greater omentum

the stomach to another viscus. The

Omenta are two-layered folds of peritoneum that connect

the portal canals between the liver lobules; the dark blue tributaries of many of the hepatic veins can also be seen.

corrosive fluid to remove the liver tissue. Note the profuse branching of the portal vein as its white terminal branches enter

and gallbladder have been injected with yellow plastic and the hepatic artery with red plastic. The liver was then immersed in

transfused with white plastic and the inferior vena cava with dark blue plastic. Outside the liver, the distended biliary ducts

Omenta

-

-

Mesenteries

-

the

and the

-

Peritoneal Pouches, Recesses, Spaces,

and Gutters

Lesser Sac

-

inferior vena cava

left triangular ligament

falciform ligament

right lobe of

liver

left lobe of liver

fundus of gallbladder

ligamentum teres

A

B

C

falciform ligament

hepatic veins

right lobe of

liver

bare area

right triangular

ligament

coronary

ligament

bile duct

left lobe of liver

ligamentum

venosum

left triangular

ligament

caudate

lobe

lesser

omentum

coronary

ligament

inferior

vena

cava

left triangular

ligament

ligamentum

venosum

right lobe of liver

left lobe

of liver

hepatic artery

portal vein

ligamentum

teres within

falciform

ligament

quadrate

lobe of

liver

gallbladder

cystic duct joining

bile duct

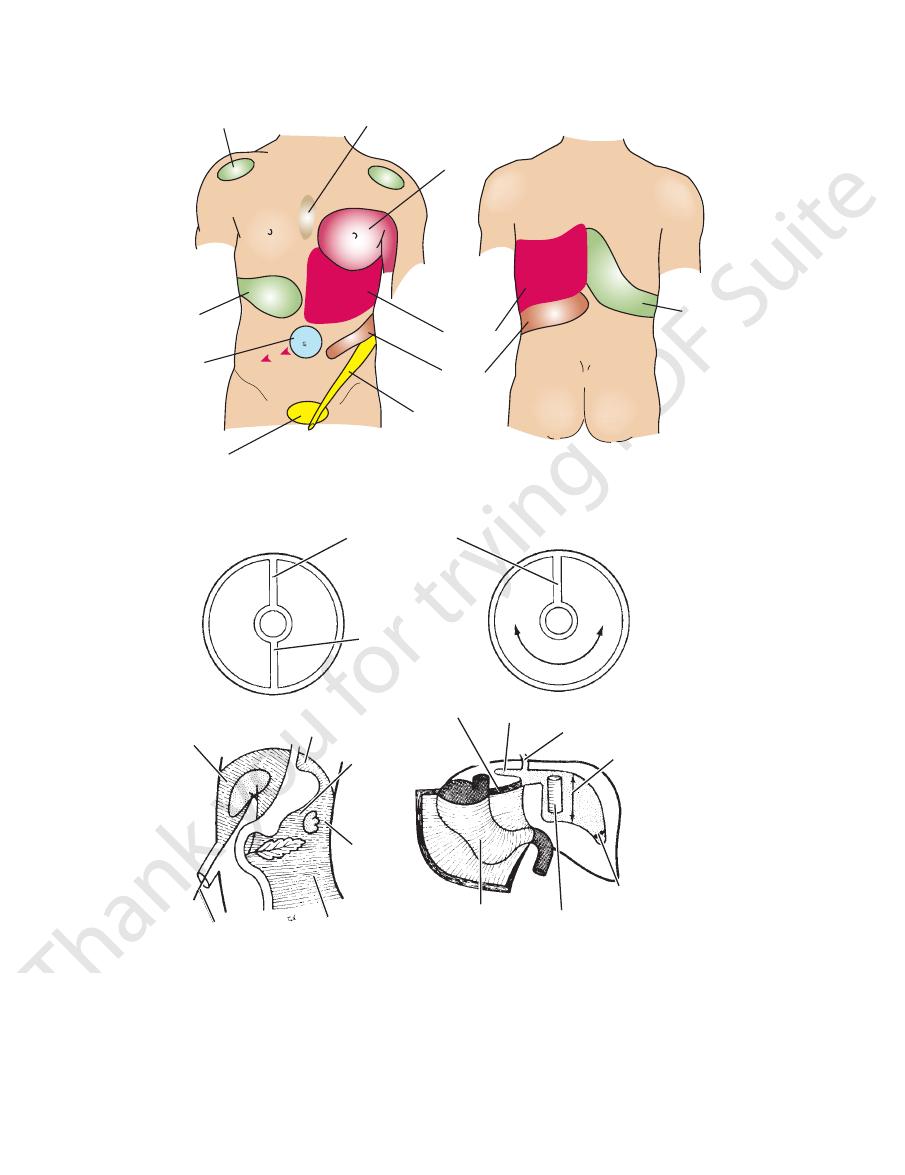

FIGURE 5.8

Liver as seen from in front

from above

(A),

(B),

and from behind (C). Note the position of the peritoneal

reflections, the bare areas, and the peritoneal ligaments.

Basic Anatomy

163

greater omentum

left suprarenal

gland

celiac artery

aorta

portal vein

inferior vena cava

stomach

bile duct

hepatic artery

lesser omentum

short gastric

arteries

gastrosplenic

omentum

cavity of lesser sac

diaphragm

splenicorenal ligament

splenic artery

FIGURE 5.11

Transverse section of the lesser sac showing the arrangement of the peritoneum in the formation of the lesser

the ascending and descending colons, respectively (Figs. 5.5

The paracolic gutters lie on the lateral and medial sides of

Paracolic Gutters

(see page 196).

is therefore situated between the liver and the diaphragm

lies between the layers of the coronary ligament and

space

right extraperitoneal

the right colic flexure (Fig. 5.15). The

lies between the right lobe of the liver, the right kidney, and

right posterior subphrenic space

ligament (Fig. 5.14). The

the diaphragm and the liver, on each side of the falciform

lie between

left anterior subphrenic spaces

right

The

Subphrenic Spaces

mouth opens downward.

V-shaped root of the sigmoid mesocolon (Fig. 5.13); its

The intersigmoid recess is situated at the apex of the inverted,

Intersigmoid Recess

(Fig. 5.13).

retrocecal recesses

ileocecal,

inferior

superior ileocecal,

toneal recesses called the

Folds of peritoneum close to the cecum produce three peri

(Fig. 5.12).

roduodenal recesses

ret

rior duodenal, inferior duodenal, paraduodenal,

supe

small pocketlike pouches of peritoneum called the

Close to the duodenojejunal junction, there may be four

First part of the duodenum

Inferiorly:

liver

Caudate process of the caudate lobe of the

Superiorly:

Inferior vena cava

Posteriorly:

duct, the hepatic artery, and the portal vein (Fig. 5.11)

Free border of the lesser omentum, the bile

Anteriorly:

the following boundaries (Fig. 5.7):

The opening into the lesser sac (epiploic foramen) has

(Fig. 5.7).

epiploic foramen

or

ing of the lesser sac,

open

(the main part of the peritoneal cavity) through the

nal ligament. The right margin opens into the greater sac

(Fig. 5.11) and the gastrosplenic omentum and splenicore

omentum. The left margin of the sac is formed by the spleen

Arrow

omentum, the gastrosplenic omentum, and the splenicorenal ligament.

indicates the position of the opening of the

lesser sac.

-

-

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

Duodenal Recesses

-

and

-

Cecal Recesses

-

the

and the

and

and 5.14).

lesser omentum

falciform ligament

caudate lobe

liver

inferior vena cava

coronary

ligament

right triangular

ligament

duodenum

greater

omentum

left triangular ligament

FIGURE 5.10

Attachment of the lesser omentum to the

stomach and the posterior surface of the liver.

164

CHAPTER 5

mechanical stretching.

enteries of the small and large intestines are sensitive to

tion of a viscus leads to the sensation of pain. The mes

the viscera or are traveling in the mesenteries. Overdisten

ture. It is supplied by autonomic afferent nerves that supply

tearing and is not sensitive to touch, pressure, or tempera

is sensitive only to stretch and

visceral peritoneum

The

nerve, a branch of the lumbar plexus.

toneum in the pelvis is mainly supplied by the obturator

plied by the lower six thoracic nerves. The parietal peri

nerves; peripherally, the diaphragmatic peritoneum is sup

of the diaphragmatic peritoneum is supplied by the phrenic

innervate the overlying muscles and skin. The central part

racic and 1st lumbar nerves—that is, the same nerves that

anterior abdominal wall is supplied by the lower six tho

touch, and pressure. The parietal peritoneum lining the

is sensitive to pain, temperature,

parietal peritoneum

The

and movement of infected peritoneal fluid (see page 165).

ically important because they may be sites for the collection

The subphrenic spaces and the paracolic gutters are clin

The Abdomen: Part II—The Abdominal Cavity

-

Nerve Supply of the Peritoneum

-

-

-

-

-

-

diaphragm

falciform ligament

left anterior

subphrenic space

stomach

phrenicocolic

ligament

left lateral

paracolic gutter

right lateral

paracolic gutter

right posterior

subphrenic space

liver

right anterior

subphrenic space

FIGURE 5.14

Normal direction of flow of the peritoneal fluid

toneum is extensive in the region of the diaphragm and the

This can be explained on the basis that the area of peri

subperitoneal lymphatic capillaries.

uous (Fig. 5.14), and there it is quickly absorbed into the

toneal movement of fluid toward the diaphragm is contin

whatever the position of the body. It seems that intraperi

cavity reaches the subphrenic peritoneal spaces rapidly,

late matter introduced into the lower part of the peritoneal

not static. Experimental evidence has shown that particu

movements of the intestinal tract, the peritoneal fluid is

and the abdominal muscles, together with the peristaltic

another. As a result of the movements of the diaphragm

and ensures that the mobile viscera glide easily on one

viscid, contains leukocytes. It is secreted by the peritoneum

The peritoneal fluid, which is pale yellow and somewhat

from different parts of the peritoneal cavity to the sub-

phrenic spaces.

Functions of the Peritoneum

-

-

-

-

ligament of Treitz

fourth part of

duodenum

retroduodenal

recess

inferior duodenal recess

inferior

mesentericvein

paraduodenal

recess

superior duodenal recess

FIGURE 5.12

Peritoneal recesses, which may be present in

forming the paraduodenal recess.

ence of the inferior mesenteric vein in the peritoneal fold,

the region of the duodenojejunal junction. Note the pres-

vascular fold

mesentery of

small intestine

ileum

mesoappendix

cecum

sigmoid mesocolon

left ureter

intersigmoid recess

sigmoid

colon

appendix

bloodless fold

ascending

colon

left common

iliac artery

FIGURE 5.13

Peritoneal recesses (arrows) in the region of the cecum and the recess related to the sigmoid mesocolon.

Basic Anatomy

be found in the greater omentum.

ments and mesenteries, and especially large amounts can

Large amounts of fat are stored in the peritoneal liga

and nerves to these organs.

serve as a means of conveying the blood vessels, lymphatics,

ing the various organs within the peritoneal cavity and

The peritoneal folds play an important part in suspend

intraperitoneal infections are sealed off and remain localized.

surfaces around a focus of infection. In this manner, many of the

neighboring intestinal tract, may adhere to other peritoneal

which is kept constantly on the move by the peristalsis of the

together in the presence of infection. The greater omentum,

The peritoneal coverings of the intestine tend to stick

the lymph vessels.

respiratory movements of the diaphragm aid lymph flow in

165

-

-

The Peritoneum and Peritoneal Cavity

wall rebounds, resulting in extreme local pain, which is known

stretching. This fact is made use of clinically in diagnosing peri

is therefore of the somatic type and can be precisely localized; it

supplied by the lower six thoracic nerves and the first lumbar

dix and wrap itself around the infected organ (Fig. 5.16). By this

Later, however, in an acutely inflamed appendix, for example, the

it is poorly developed and thus is less protective in a young child.

istaltic movements of the neighboring gut. In the first 2 years of life,

The lower and the right and left margins are

The greater omentum is often referred to by the surgeons as the

origin as the phrenic nerve, which supplies the peritoneum in the

over the shoulder. (This also holds true for collections of blood

in females (gonococcal peritonitis in adults and pneumococcal

bladder, through the anterior abdominal wall, via the uterine tubes

paracolic gutters (Fig. 5.15). The attachment of the transverse

abdomen and a lower part in the pelvis. The abdominal part is

Movement of Peritoneal Fluid

The peritoneal cavity is divided into an upper part within the

further subdivided by the many peritoneal reflections into impor-

tant recesses and spaces, which, in turn, are continued into the

mesocolon and the mesentery of the small intestine to the poste-

rior abdominal wall provides natural peritoneal barriers that may

hinder the movement of infected peritoneal fluid from the upper

part to the lower part of the peritoneal cavity.

It is interesting to note that when the patient is in the supine

position the right subphrenic peritoneal space and the pel-

vic cavity are the lowest areas of the peritoneal cavity and the

region of the pelvic brim is the highest area (Fig. 5.15).

Peritoneal Infection

Infection may gain entrance to the peritoneal cavity through sev-

eral routes: from the interior of the gastrointestinal tract and gall-

peritonitis in children occur through this route), and from the blood.

Collection of infected peritoneal fluid in one of the subphrenic

spaces is often accompanied by infection of the pleural cavity. It

is common to find a localized empyema in a patient with a sub-

phrenic abscess. It is believed that the infection spreads from

the peritoneum to the pleura via the diaphragmatic lymph ves-

sels. A patient with a subphrenic abscess may complain of pain

under the diaphragm, which irritate the parietal diaphragmatic

peritoneum.) The skin of the shoulder is supplied by the supra-

clavicular nerves (C3 and 4), which have the same segmental

center of the undersurface of the diaphragm.

To avoid the accumulation of infected fluid in the subphrenic

spaces and to delay the absorption of toxins from intraperitoneal

infections, it is common nursing practice to sit a patient up in

bed with the back at an angle of 45°. In this position, the infected

peritoneal fluid tends to gravitate downward into the pelvic cav-

ity, where the rate of toxin absorption is slow (Fig. 5.15).

Greater Omentum

Localization of Infection

abdominal policeman.

free, and it moves about the peritoneal cavity in response to the per-

inflammatory exudate causes the omentum to adhere to the appen-

means, the infection is often localized to a small area of the perito-

neal cavity, thus saving the patient from a serious diffuse peritonitis.

Greater Omentum as a Hernial Plug

The greater omentum has been found to plug the neck of a her-

nial sac and prevent the entrance of coils of small intestine.

Greater Omentum in Surgery

Surgeons sometimes use the omentum to buttress an intestinal

anastomosis or in the closure of a perforated gastric or duodenal

ulcer.

Torsion of the Greater Omentum

The greater omentum may undergo torsion, and if extensive, the

blood supply to a part of it may be cut off, causing necrosis.

Ascites

Ascites is essentially an excessive accumulation of peritoneal

fluid within the peritoneal cavity. Ascites can occur secondary to

hepatic cirrhosis (portal venous congestion), malignant disease

(e.g., cancer of the ovary), or congestive heart failure (systemic

venous congestion). In a thin patient, as much as 1500 mL has to

accumulate before ascites can be recognized clinically. In obese

individuals, a far greater amount has to collect before it can be

detected. The withdrawal of peritoneal fluid from the peritoneal

cavity is described on page 148.

Peritoneal Pain

From the Parietal Peritoneum

The parietal peritoneum lining the anterior abdominal wall is

nerve. Abdominal pain originating from the parietal peritoneum

is usually severe (see Abdominal Pain, page 224).

An inflamed parietal peritoneum is extremely sensitive to

-

tonitis. Pressure is applied to the abdominal wall with a single

finger over the site of the inflammation. The pressure is then

removed by suddenly withdrawing the finger. The abdominal

as rebound tenderness.

(continued)

C L I N I C A L N O T E S

166

CHAPTER 5

The Abdomen: Part II—The Abdominal Cavity

It should always be remembered that the parietal peritoneum

catheter through a small midline incision through the anterior

referred to the midline. Pain arising from an abdominal viscus is

a midline structure and receives a bilateral nerve supply, pain is

of a viscus or pulling on a mesentery gives rise to the sensation of

by autonomic afferent nerves. Stretch caused by overdistension

The visceral peritoneum, including the mesenteries, is innervated

in the pelvis is innervated by the obturator nerve and can be pal-

pated by means of a rectal or vaginal examination. An inflamed

appendix may hang down into the pelvis and irritate the parietal

peritoneum. A pelvic examination can detect extreme tender-

ness of the parietal peritoneum on the right side (see page 268).

From the Visceral Peritoneum

pain. The sites of origin of visceral pain are shown in Figure 5.17.

Because the gastrointestinal tract arises embryologically as

dull and poorly localized (see Abdominal Pain, page 224).

Peritoneal Dialysis

Because the peritoneum is a semipermeable membrane, it

allows rapid bidirectional transfer of substances across itself.

Because the surface area of the peritoneum is enormous, this

transfer property has been made use of in patients with acute

renal insufficiency. The efficiency of this method is only a frac-

tion of that achieved by hemodialysis.

A watery solution, the dialysate, is introduced through a

abdominal wall below the umbilicus. The technique is the same

as peritoneal lavage (see page 148). The products of metabolism,

such as urea, diffuse through the peritoneal lining cells from

the blood vessels into the dialysate and are removed from the

patient.

Internal Abdominal Hernia

Occasionally, a loop of intestine enters a peritoneal pouch

or recess (e.g., the lesser sac or the duodenal recesses) and

becomes strangulated at the edges of the recess. Remember

that important structures form the boundaries of the entrance

into the lesser sac and that the inferior mesenteric vein often lies

in the anterior wall of the paraduodenal recess.

Development of the Peritoneum and the

The inferior recess of the lesser sac extends inferiorly between the

As development proceeds, the omentum becomes laden with fat.

attached to the anterior surface of the transverse colon (Fig. 5.19).

verse mesocolon; as a result, the greater omentum becomes

tery, and the greater omentum is formed as a result of the rapid

, and the two

greater sac

included in the lesser sac, is called the

The right free border of the ventral mesentery becomes the right

tral mesentery to the right and causes rotation of the stomach

and

greater omentum,

the

splenicorenal ligament,

the

of the abdominal part of the gut (Figs. 4.36 and 5.18). The dorsal

extends from the posterior abdominal wall to the posterior border

and the

lesser omentum,

the

falciform ligament,

forms the

communication between the peritoneal cavity and extraembry

and the enlargement of the developing kidneys, the capacity of

and left halves of the peritoneal cavity are in free communica

mesentery, the gut, and the small ventral mesentery (Fig. 5.18).

folds of the embryo, this wide area of communication becomes

4.36B). Later, with the development of the head, tail, and lateral

munication with the extraembryonic coelom on each side (Fig.

sum. In the earliest stages, the peritoneal cavity is in free com

The peritoneal cavity is derived from that part

layers, a cavity is formed between the two, called the

Once the lateral mesoderm has split into somatic and splanchnic

Peritoneal Cavity

intraem-

bryonic coelom.

of the embryonic coelom situated caudal to the septum transver-

-

restricted to the small area within the umbilical cord.

Early in development, the peritoneal cavity is divided into

right and left halves by a central partition formed by the dorsal

However, the ventral mesentery extends only for a short dis-

tance along the gut (see below), so that below this level the right

-

tion (Fig. 5.18). As a result of the enormous growth of the liver

the abdominal cavity becomes greatly reduced at about the 6th

week of development. It is at this time that the small remaining

-

onic coelom becomes important. An intestinal loop is forced out

of the abdominal cavity through the umbilicus into the umbilical

cord. This physiologic herniation of the midgut takes place dur-

ing the 6th week of development.

Formation of the Peritoneal Ligaments and Mesenteries

The peritoneal ligaments are developed from the ventral and

dorsal mesenteries. The ventral mesentery is formed from the

mesoderm of the septum transversum (derived from the cervi-

cal somites, which migrate downward). The ventral mesentery

coro-

nary and triangular ligaments of the liver (Fig. 5.18).

The dorsal mesentery is formed from the fusion of the

splanchnopleuric mesoderm on the two sides of the embryo. It

mesentery forms the gastrophrenic ligament, the gastrosplenic

omentum,

the mesenteries of the small and large intestines.

Formation of the Lesser and Greater Peritoneal Sacs

The extensive growth of the right lobe of the liver pulls the ven-

and duodenum (Fig. 5.19). By this means, the upper right part of

the peritoneal cavity becomes incorporated into the lesser sac.

border of the lesser omentum and the anterior boundary of the

entrance into the lesser sac.

The remaining part of the peritoneal cavity, which is not

sacs are in communication through the epiploic foramen.

Formation of the Greater Omentum

The spleen is developed in the upper part of the dorsal mesen-

and extensive growth of the dorsal mesentery caudal to the

spleen. To begin with, the greater omentum extends from the

greater curvature of the stomach to the posterior abdominal wall

superior to the transverse mesocolon. With continued growth,

it reaches inferiorly as an apronlike double layer of peritoneum

anterior to the transverse colon.

Later, the posterior layer of the omentum fuses with the trans-

anterior and the posterior layers of the fold of the greater omentum.

E M B R Y O L O G I C N O T E S

Basic Anatomy

167

A

B

C

FIGURE 5.16

spread of intraperitoneal infections.

omentum adherent to the base of a gastric ulcer. One important function of the greater omentum is to attempt to limit the

The greater

The greater omentum wrapped around an inflamed appendix.

The normal greater omentum.

A.

B.

C.

anterior and posterior

right subphrenic spaces

anterior left subphrenic space

right

paracolic

gutter

phrenicocolic

ligament

left

paracolic gutter

pelvic brim

right posterior subphrenic space

pelvic cavity

3

4

pelvic cavity

2

1

FIGURE 5.15

Direction of flow of the peritoneal fluid.

Accumulation of inflammatory exudate in the pelvis when the patient is nursed in the inclined position.

The two sites where inflammatory exudate tends to collect when the patient is nursed in the

tory exudate in peritonitis.

Flow of inflamma

Normal flow upward to the subphrenic spaces.

1.

2.

-

3.

supine position. 4.

168

CHAPTER 5

The Abdomen: Part II—The Abdominal Cavity

dorsal mesentery

ventral mesentery

falciform ligament

gastrophrenic ligament

gastrosplenic omentum

(ligament)

lienorenal

ligament

dorsal mesentery

umbilical vein

left triangular ligament

lesser

omentum

falciform ligament

coronary ligament

right triangular ligament

inferior vena cava

stomach

FIGURE 5.18

Ventral and dorsal mesenteries and the organs that develop within them.

gallbladder,

diaphragm

esophagus

kidney

urinary bladder

appendix

ureter

gallbladder

gallbladder

stomach

heart

FIGURE 5.17

ed in referred visceral pain.

Some important skin areas involv

The esophagus is a muscular, collapsible tube about 10 in.

Gastrointestinal Tract

Esophagus (Abdominal Portion)

(25 cm) long that joins the pharynx to the stomach. The

of the left lobe of the liver and posteriorly to the left crus

The esophagus is related anteriorly to the posterior surface

about 0.5 in. (1.25 cm), it enters the stomach on its right side.

in the right crus of the diaphragm (Fig. 5.4). After a course of

100). The esophagus enters the abdomen through an opening

greater part of the esophagus lies within the thorax (see page

Relations