The cerebellum also aids the cerebral cortex in planning the next sequential

activation of specific muscles.

not compare favorably, then instantaneous subconscious corrective signals are

information with the movements intended by the motor system. If the two do

rate of movement, forces acting on it, and so forth. The cerebellum then

receives continuous sensory information from the peripheral parts of the body,

sequence of muscle contractions from the brain motor control areas; it also

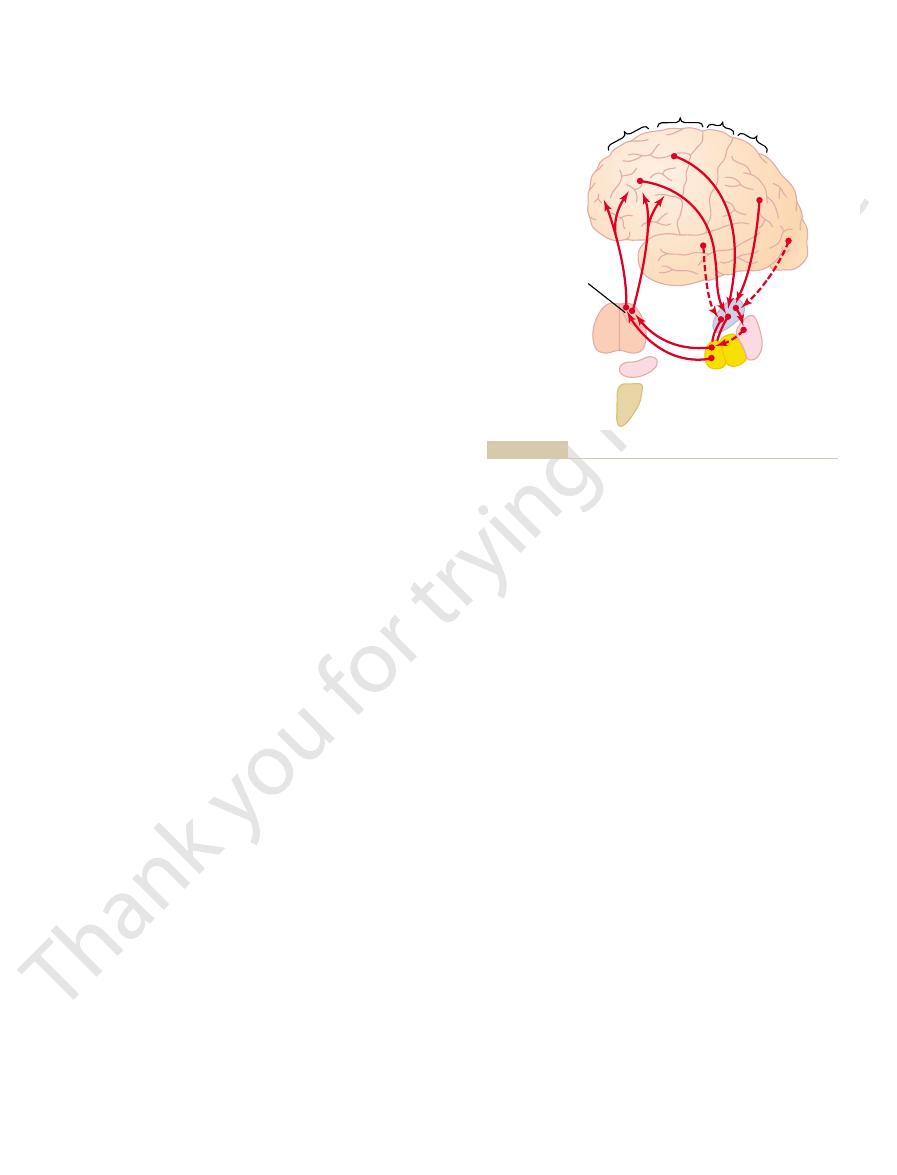

The cerebellum receives continuously updated information about the desired

the motor signals directed by the cerebral motor cortex and other parts of the

s motor activities while they are being executed so that they will conform to

ability to cause muscle contraction? The answer is that it helps to

ties even though its loss causes paralysis of no muscles.

cular activities such as running, typing, playing the piano, and even talking. Loss

become highly abnormal. The cerebellum is especially vital during rapid mus-

ment. Removal of the cerebellum, however, does cause body movements to

of the brain, principally because electrical excitation of the cerebel-

The cerebellum, illustrated in Figures 56–1 and 56–2, has long been called a

Cerebellum and Its Motor Functions

activity.

achieving specific complicated motor goals. This chapter explains the basic

movements, and sequencing of multiple successive and parallel movements for

, controlling relative intensities of the separate movements, directions of

basal ganglia help to plan and control complex patterns of muscle move-

The

interplay between agonist and antagonist muscle groups.

when the muscle load changes, as well as controlling necessary instantaneous

movement to the next. It also helps to control intensity of muscle contraction

timing of motor activities and in rapid, smooth progression from one muscle

Basically, the

they always function in associa-

themselves. Instead,

. Yet

They are the

stimulate muscle contraction, two other brain struc-

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

5

6

698

Contributions of the Cerebellum

and Basal Ganglia to Overall

Motor Control

Aside from the areas in the cerebral cortex that

tures are also essential for normal motor function.

cerebellum and the basal ganglia

neither of these two can control muscle function by

tion with other systems of motor control.

cerebellum plays major roles in the

ment

mechanisms of function of the cerebellum and basal ganglia and discusses the

overall brain mechanisms for achieving intricate coordination of total motor

silent area

lum does not cause any conscious sensation and rarely causes any motor move-

of this area of the brain can cause almost total incoordination of these activi-

But how is it that the cerebellum can be so important when it has no direct

sequence

the motor activities and also monitors and makes corrective adjustments in the

body’

brain.

giving sequential changes in the status of each part of the body—its position,

com-

pares the actual movements as depicted by the peripheral sensory feedback

transmitted back into the motor system to increase or decrease the levels of

movement a fraction of a second in advance while the current movement is still

bral cortex and brain stem. In turn, they send motor

facial regions lie in the intermediate zones. These topo-

vermis part of the cerebellum, whereas the limbs and

tions. Note that the axial portions of the body lie in the

cerebellum. Figure 56–3 shows two such representa-

sentations of the different parts of the body, so also is

sensory cortex, motor cortex, basal ganglia, red nuclei,

Topographical Representation of the Body in the Vermis and Inter-

nate, as we discuss more fully later.

motor movements. Without this lateral zone, most dis-

The lateral zone of the hemisphere operates at a

hands and fingers and feet and toes.

portions of the upper and lower limbs, especially the

The intermediate zone of the hemisphere is con-

zone.

intermediate zone

, and each of these hemi-

To each side of the vermis is a large, laterally pro-

neck

cerebellum by shallow grooves. In this area, most cere-

, separated from the remainder of the

longitudinal axis, as demonstrated in Figure 56–2, which

From a functional point of view, the anterior and

controlling body equilibrium, as discussed in Chapter

oldest of all portions of the cerebellum; it developed

The flocculonodular lobe is the

flocculonodular lobe.

, and (3) the

, (2) the

by two deep fissures, as shown in Figures 56–1 and 56–2:

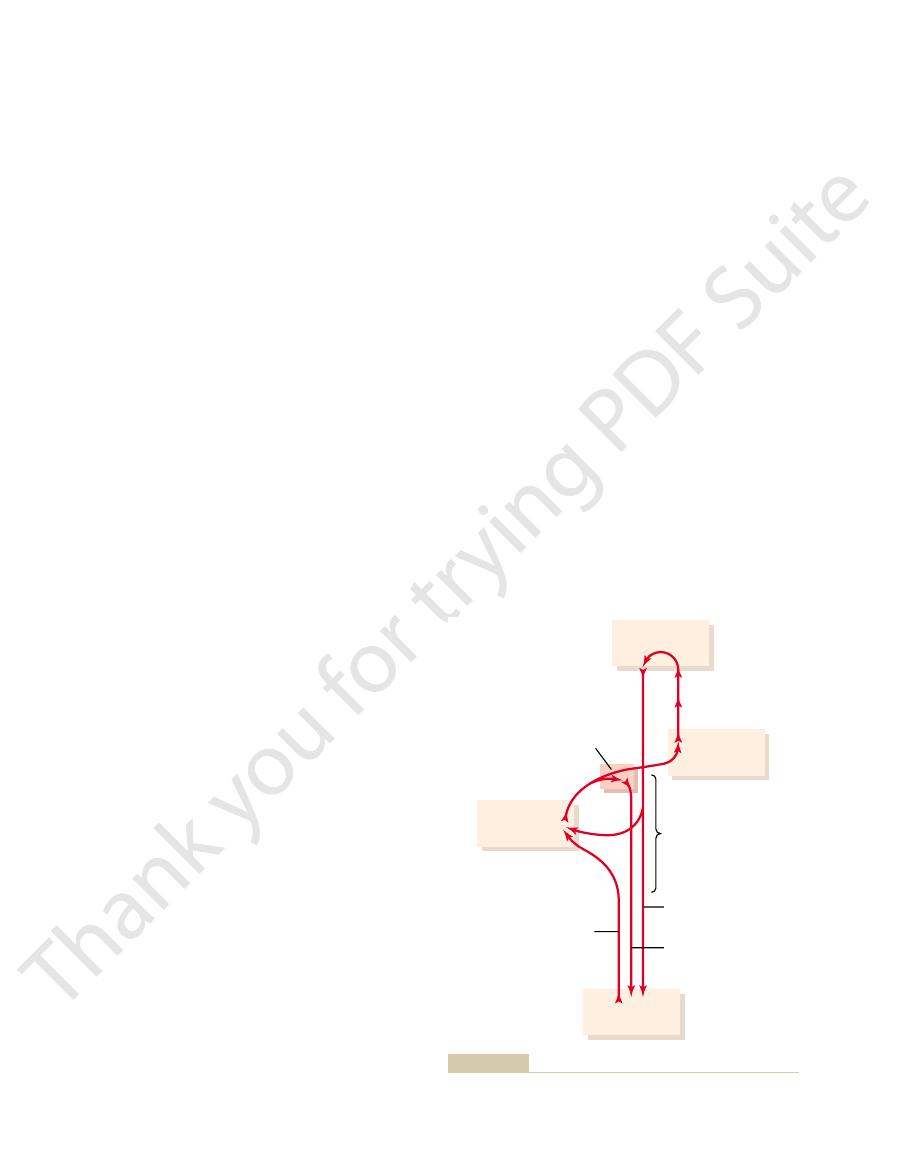

Anatomically, the cerebellum is divided into three lobes

of the Cerebellum

Anatomical Functional Areas

intended movements

priate cerebellar neurons, thus bringing subsequent

changes occur in the excitability of appro-

To do this,

to make a stronger or weaker movement the next time.

occur exactly as intended, the cerebellar circuit learns

learns by its mistakes—that is, if a movement does not

smoothly from one movement to the next. Also, it

being executed, thus helping the person to progress

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

699

muscle contractions into better correspondence with the

.

(1) the anterior lobe

posterior lobe

along with (and functions with) the vestibular system in

55.

Longitudinal Functional Divisions of the Anterior and Posterior

Lobes.

posterior lobes are organized not by lobes but along the

shows a posterior view of the human cerebellum after

the lower end of the posterior cerebellum has been

rolled downward from its normally hidden position.

Note down the center of the cerebellum a narrow band

called the vermis

bellar control functions for muscle movements of the

axial body,

, shoulders, and hips are located.

truding cerebellar hemisphere

spheres is divided into an

and a lateral

cerned with controlling muscle contractions in the distal

much more remote level because this area joins with the

cerebral cortex in the overall planning of sequential

crete motor activities of the body lose their appropriate

timing and sequencing and therefore become incoordi-

mediate Zones.

In the same manner that the cerebral

and reticular formation all have topographical repre-

this true for the vermis and intermediate zones of the

graphical representations receive afferent nerve signals

from all the respective parts of the body as well as from

corresponding topographical motor areas in the cere-

Pons

Anterior lobe

Posterior lobe

Medulla

Flocculonodular

lobe

Anatomical lobes of the cerebellum as seen from the lateral side.

Figure 56–1

Hemisphere

Vermis

Vermis

Intermediate zone

of hemisphere

Anterior

lobe

Posterior

lobe

Lateral zone

of hemisphere

Flocculonodular

lobe

outward to flatten the surface.

rior view, with the inferiormost portion of the cerebellum rolled

Functional parts of the cerebellum as seen from the posteroinfe-

Figure 56–2

Somatosensory projection areas in the cerebellar cortex.

Figure 56–3

Thus, this ventral fiber pathway tells the cerebellum

the internal motor pattern generators in the cord itself.

less information from the peripheral receptors. Instead,

Conversely, the ventral spinocerebellar tracts receive

surfaces of the body.

of the parts of the body, and (4) forces acting on the

muscle tendons, (3) positions and rates of movement

of (1) muscle contraction, (2) degree of tension on the

receptors of the skin, and joint receptors. All these

the body, such as Golgi tendon organs, large tactile

The signals transmitted in the dorsal spinocerebellar

through the superior cerebellar peduncle, but it termi-

as its origin. The ventral tract enters the cerebellum

The

tracts are shown in Figure 56–5: the

cord and two ventrally. The two most important of these

on each side, two of which are located dorsally in the

The cerebellum also

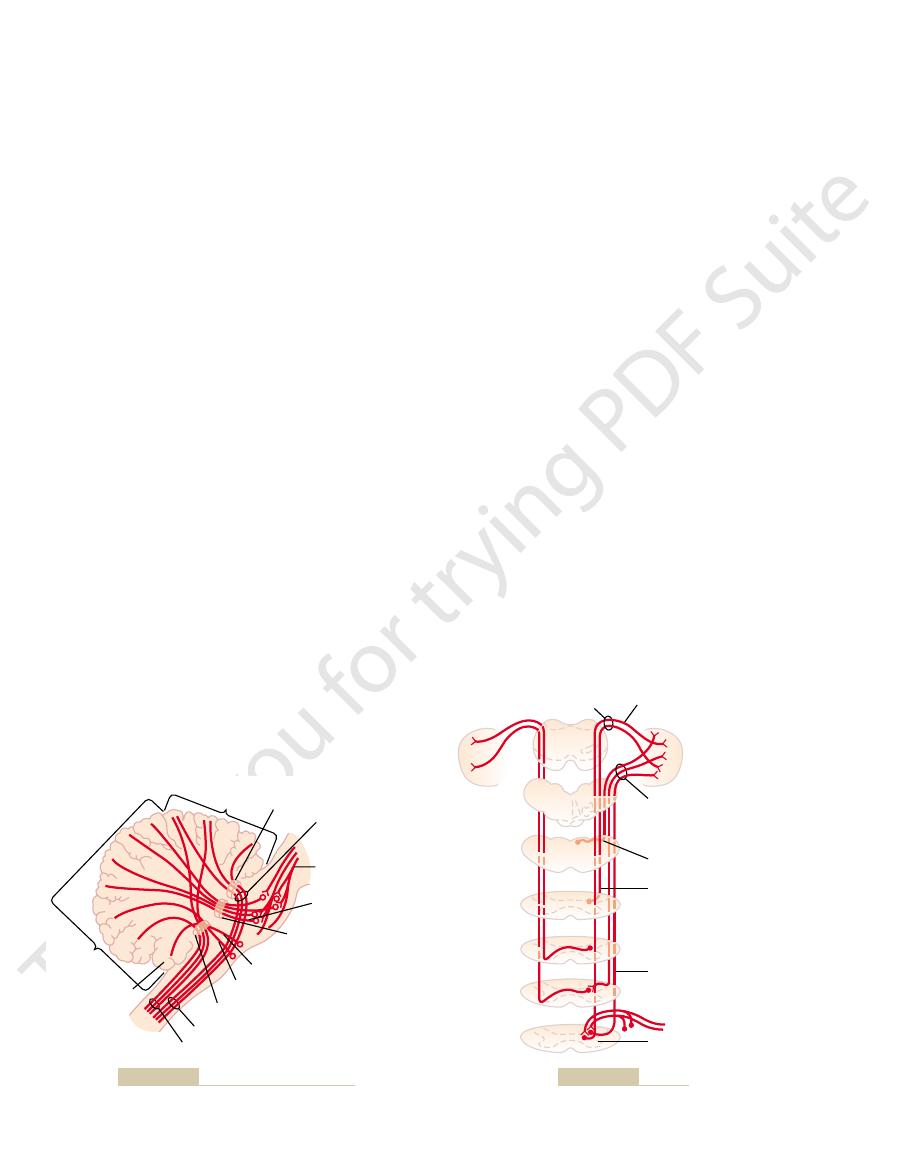

Afferent Pathways from the Periphery.

, which originate in different portions of the brain

of the cerebellum; and (3)

, some of which

; (2)

spinal cord

, and

, widespread areas of the

, which passes from the

each side of the brain stem; they include (1) an exten-

In addition, important afferent tracts originate in

the opposite side of the brain from the cerebral areas.

, which originates in

corticopontocerebellar pathway

56–4. An extensive and important afferent pathway is

input pathways to the cerebellum are shown in Figure

The basic

56–2 and 56–3. Each fold is called a folium. Lying deep

long, with the folds lying crosswise, as shown in Figures

sheet, about 17 centimeters wide by 120 centimeters

The human cerebellar cortex is actually a large folded

Neuronal Circuit of the Cerebellum

important roles in planning and coordinating the body’s

association areas of the parietal cortex. It is believed

cortex, especially from the premotor areas of the frontal

of the body. These areas of the cerebellum receive their

of the cerebral motor cortex, as well as to topographi-

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

700

Unit XI

signals back to the same respective topographical areas

cal areas of the red nucleus and reticular formation in

the brain stem.

Note that the large lateral portions of the cerebellar

hemispheres do not have topographical representations

input signals almost exclusively from the cerebral

cortex and from the somatosensory and other sensory

that this connectivity with the cerebral cortex allows the

lateral portions of the cerebellar hemispheres to play

rapid sequential muscular activities that occur one after

another within fractions of a second.

beneath the folded mass of cerebellar cortex are deep

cerebellar nuclei.

Input Pathways to the Cerebellum

Afferent Pathways from Other Parts of the Brain.

the

the cerebral motor and premotor cortices and also in the

cerebral somatosensory cortex. It passes by way of the

pontile nuclei and pontocerebellar tracts mainly to

the lateral divisions of the cerebellar hemispheres on

sive olivocerebellar tract

inferior

olive to all parts of the cerebellum and is excited in the

olive by fibers from the cerebral motor cortex, basal

ganglia

reticular formation

vestibulocerebellar fibers

originate in the vestibular apparatus itself and others

from the brain stem vestibular nuclei—almost all of

these terminate in the flocculonodular lobe and fastigial

nucleus

reticulocerebellar

fibers

stem reticular formation and terminate in the midline

cerebellar areas (mainly in the vermis).

receives important sensory signals directly from the

peripheral parts of the body mainly through four tracts

dorsal spinocere-

bellar tract and the ventral spinocerebellar tract.

dorsal tract enters the cerebellum through the inferior

cerebellar peduncle and terminates in the vermis and

intermediate zones of the cerebellum on the same side

nates in both sides of the cerebellum.

tracts come mainly from the muscle spindles and to a

lesser extent from other somatic receptors throughout

signals apprise the cerebellum of the momentary status

they are excited mainly by motor signals arriving in the

anterior horns of the spinal cord from (1) the brain

through the corticospinal and rubrospinal tracts and (2)

Superior cerebellar

peduncle

Ventral

spinocerebellar

tract

Cerebropontile

tract

Pontocerebellar

tract

Middle cerebellar

peduncle

Vestibulocerebellar tract

Olivocerebellar and

reticulocerebellar tract

Inferior cerebellar peduncle

Ventral spinocerebellar tract

Dorsal spinocerebellar tract

Flocculonodular

lobe

Anterior

lobe

Posterior

lobe

tracts to the cerebellum.

afferent

Figure 56–4

Principal

Superior cerebellar peduncle

Dorsal spinocerebellar tract

Clark’s cells

Spinal cord

Ventral spinocerebellar tract

Dorsal external arcuate fiber

Medulla oblongata

Inferior cerebellar peduncle

Ventral spinocerebellar tract

Cerebellum

Spinocerebellar tracts.

Figure 56–5

. There is one climbing fiber for

The climbing fibers

two types, one called the

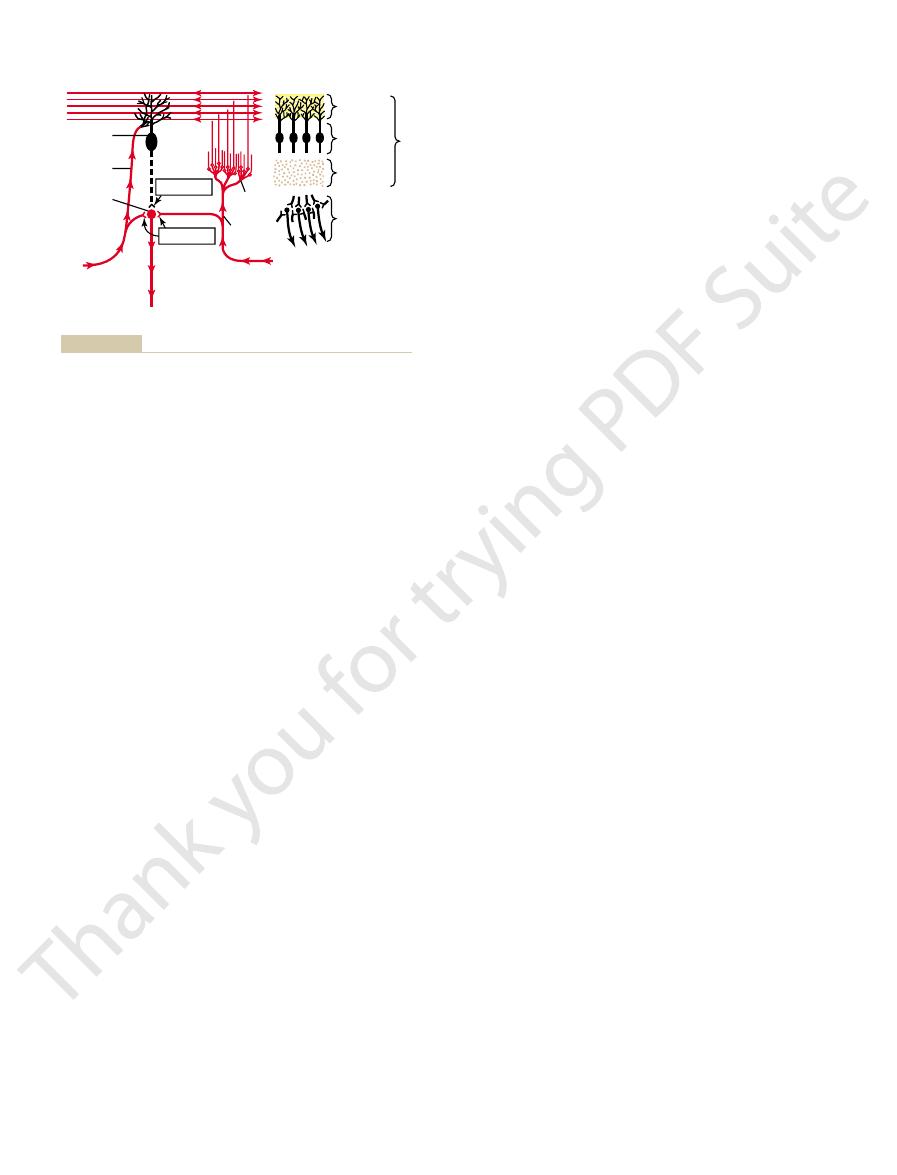

The afferent inputs to the cerebellum are mainly of

bellum from the brain or the periphery. The inhibitory

influences. The excitatory influences arise from direct

. This cell

30 million times in the cerebellum. The output from

functional unit, which is repeated with little variation

left half of Figure 56–7 is the neuronal circuit of the

bellar mass, are the deep cerebellar nuclei that send

Beneath these cortical layers, in the center of the cere-

granule cell layer

, and

Purkinje cell layer

lar layer

layers of the cerebellar cortex are shown: the

To the top and right in Figure 56–7, the three major

Figure 56–7. This functional unit centers on a single,

functional units, one of which is shown to the left in

The cerebellum has about 30 million nearly identical

Functional Unit of the Cerebellar Cortex—

thalamus, and, finally, to the cerebral cortex. This

then passes to the dentate nucleus, next to the

3. A pathway that begins in the cerebellar cortex of

limbs, especially in the hands, fingers, and thumbs.

brain stem. This complex circuit helps to coordinate

thalamus and then to (4) the cerebral cortex, to (5)

2. A pathway that originates in (1) the intermediate

postural attitudes of the body. It was discussed in

control equilibrium, and also in association with the

This circuit

1. A pathway that originates in the

leading out of the cerebellum is shown in Figure 56–6

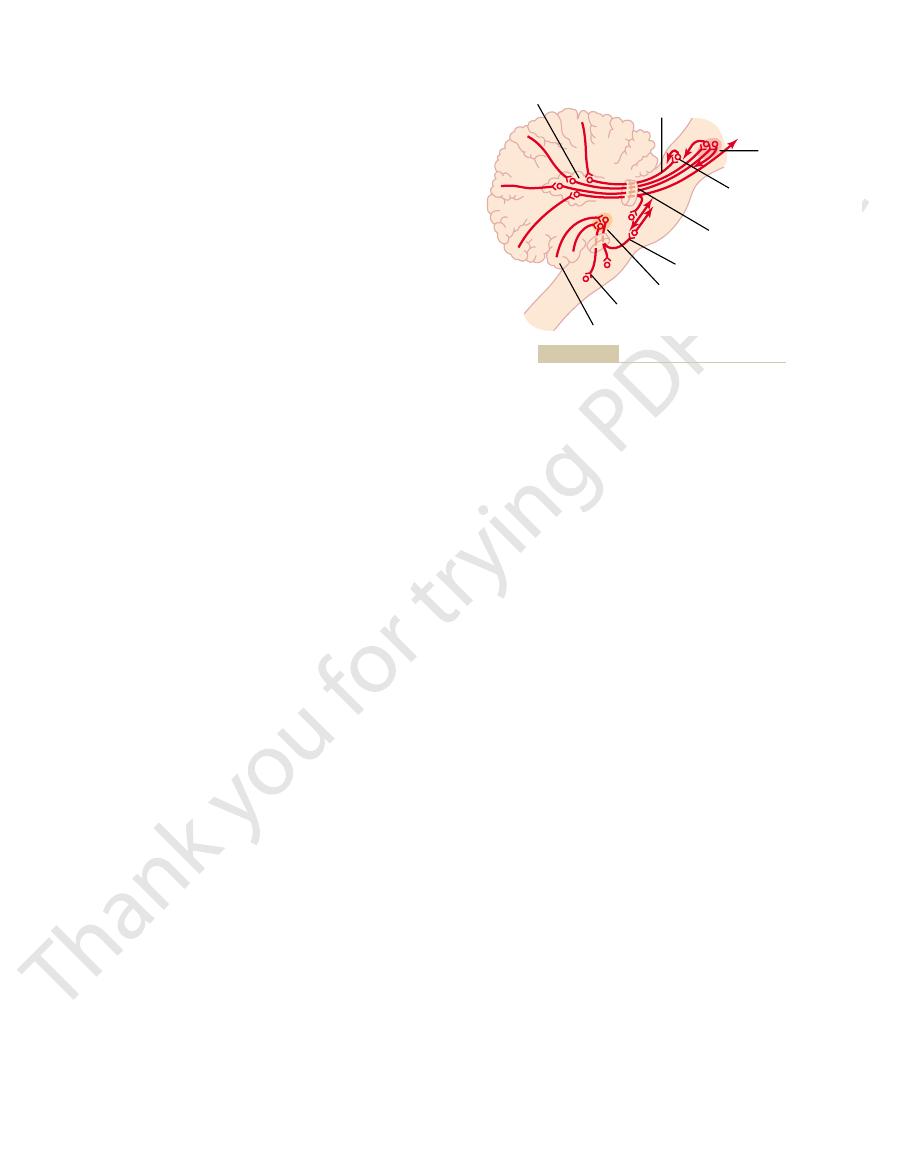

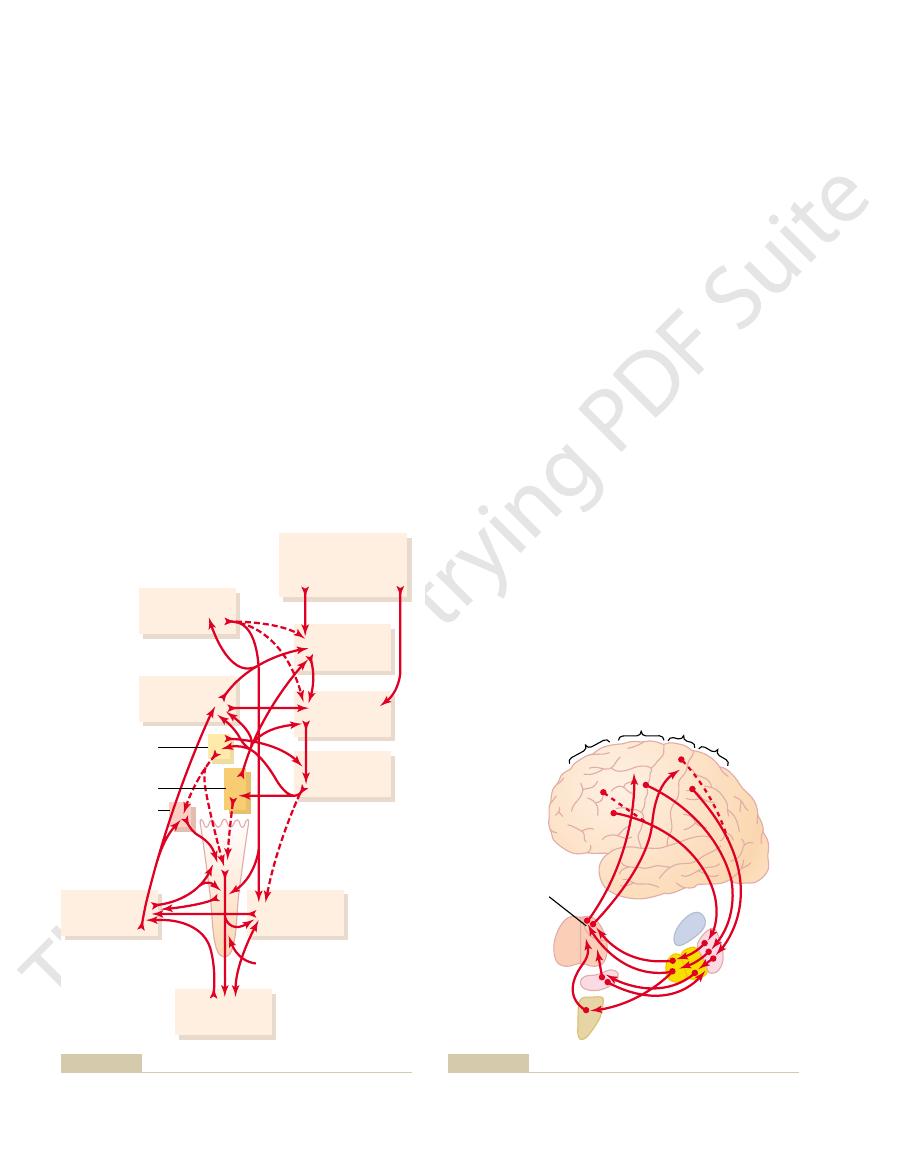

The general plan of the major efferent pathways

inhibitory signals. From the deep nuclei, output signals

Thus, all input signals that enter the cerebellum even-

output signal to the deep nucleus.

Then, a fraction of a second later, the cerebellar cortex

area of the cerebellar cortex overlying the deep nucleus.

it divides and goes in two directions: (1) directly to one

receive signals from two sources: (1) the cerebellar

the flocculonodular lobe.) All the deep cerebellar nuclei

(The

, and

these areas to the cerebellum. Thus, the cerebellum con-

olivary nucleus. Then signals are relayed from both of

spino-olivary pathway

spinoreticular pathway

to the cerebellum. Likewise, signals are transmitted up

In addition to signals from the spinocerebellar tracts,

in peripheral muscle actions.

system. This extremely rapid conduction is important

at velocities up to 120 m/sec, which is the most rapid

The spinocerebellar pathways can transmit impulses

horn motor drive.

efference copy

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

701

which motor signals have arrived at the anterior horns;

this feedback is called the

of the anterior

conduction in any pathway in the central nervous

for instantaneous apprisal of the cerebellum of changes

signals are transmitted into the cerebellum from the

body periphery through the spinal dorsal columns to the

dorsal column nuclei of the medulla and then relayed

the spinal cord through the

to

the reticular formation of the brain stem and also

through the

to the inferior

tinually collects information about the movements and

positions of all parts of the body even though it is oper-

ating at a subconscious level.

Output Signals from the Cerebellum

Deep Cerebellar Nuclei and the Efferent Pathways.

Located

deep in the cerebellar mass on each side are three deep

cerebellar nuclei—the dentate, interposed

fastigial.

vestibular nuclei in the medulla also function in

some respects as if they were deep cerebellar nuclei

because of their direct connections with the cortex of

cortex and (2) the deep sensory afferent tracts to the

cerebellum.

Each time an input signal arrives in the cerebellum,

of the cerebellar deep nuclei and (2) to a corresponding

relays an inhibitory

tually end in the deep nuclei in the form of initial exci-

tatory signals followed a fraction of a second later by

leave the cerebellum and are distributed to other parts

of the brain.

and consists of the following:

midline structures

of the cerebellum (the vermis) and then passes

through the fastigial nuclei into the medullary and

pontile regions of the brain stem.

functions in close association with the equilibrium

apparatus and brain stem vestibular nuclei to

reticular formation of the brain stem to control the

detail in Chapter 55 in relation to equilibrium.

zone of the cerebellar hemisphere and then passes

through (2) the interposed nucleus to (3) the

ventrolateral and ventroanterior nuclei of the

several midline structures of the thalamus and then

to (6) the basal ganglia and (7) the red nucleus and

reticular formation of the upper portion of the

mainly the reciprocal contractions of agonist and

antagonist muscles in the peripheral portions of the

the lateral zone of the cerebellar hemisphere and

ventrolateral and ventroanterior nuclei of the

pathway plays an important role in helping

coordinate sequential motor activities initiated by

the cerebral cortex.

The Purkinje Cell and the Deep Nuclear Cell

very large Purkinje cell (30 million of which are in

the cerebellar cortex) and on a corresponding deep

nuclear cell.

molecu-

,

.

output signals to other parts of the nervous system.

Neuronal Circuit of the Functional Unit.

Also shown in the

the functional unit is from a deep nuclear cell

is continually under both excitatory and inhibitory

connections with afferent fibers that enter the cere-

influence arises entirely from the Purkinje cell in the

cortex of the cerebellum.

climbing fiber type and the

other called the mossy fiber type.

all originate from the inferior

olives of the medulla

Fastigioreticular tract

Cerebellothalamocortical

tract

Dentate

Superior cerebellar

peduncle

Reticulum of

mesencephalon

Red nucleus

To thalamus

Fastigioreticular tract

Fastigial nucleus

Paleocerebellum

tracts from the cerebellum.

efferent

Figure 56–6

Principal

are not fully known, one can speculate from the basic

signals to the antagonists. Although the exact details

on approaching termination of the movement, the

antagonist muscles at the onset of a movement. Then

The typical function of the cerebellum is to help

Signals from the Cerebellum

Turn-On/Turn-Off and Turn-Off/Turn-On Output

of adjacent Purkinje cells, thus sharpening

right angles across the parallel fibers and cause

parallel fibers. These cells in turn send their axons at

lar cortex, lying among and stimulated by the small

with short axons. Both the basket cells and the stellate

. These are inhibitory cells

deep nuclear cells, granule cells, and Purkinje cells, two

Other Inhibitory Cells in the Cerebellum.

occur.

mark. Otherwise, oscillation of the movement would

. That is, when the motor system is excited,

signal resembles a “delay-line” negative feedback

of a second by an inhibitory signal. This inhibitory

ment, but this is followed within another small fraction

circuit arrive. In this way, there is first a rapid excita-

cell excitation. Then, another few milliseconds later,

In execution of a rapid motor movement, the

tation, so that, under quiet conditions, output from the

the Purkinje cells inhibit them. Normally, the balance

fibers excites them. By contrast, signals arriving from

56–7, one should note that direct stimulation of the

Referring again to the circuit of Figure

more, the output activity of both these cells can be

the deep nuclear cells at much higher rates. Further-

at about 50 to 100 action potentials per second, and

both of them fire continuously; the Purkinje cell fires

, rather than the prolonged complex action

excite the Purkinje cell. Furthermore, activation

synaptic connections are weak, so that large numbers

The mossy fiber input to the Purkinje cell is quite

project and 80,000 to 200,000 of the parallel fibers

granule cells for every 1 Purkinje cell. It is into this

because there are some 500 to 1000

lel to the folia. There are many millions of these

bellar cortex. Here the axons divide into two branches

small axons, less than 1 micrometer in diameter, up to

. In turn, the granule cells send very, very

send collaterals to excite the deep nuclear cells. Then

brain, brain stem, and spinal cord. These fibers also

the cerebellum from multiple sources: from the higher

The mossy fibers are all the other fibers that enter

secondary spikes. This action potential is called the

Purkinje cell with which it connects, beginning with

second), peculiar type of action potential in each

in it will always cause a single, prolonged (up to 1

and dendrites of each Purkinje cell. This climbing

several deep nuclear cells, the climbing fiber continues

about 5 to 10 Purkinje cells. After sending branches to

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

702

Unit XI

all the way to the outer layers of the cerebellar cortex,

where it makes about 300 synapses with the soma

fiber is distinguished by the fact that a single impulse

a strong spike and followed by a trail of weakening

complex spike.

they proceed to the granule cell layer of the cortex,

where they too synapse with hundreds to thousands of

granule cells

the molecular layer on the outer surface of the cere-

that extend 1 to 2 millimeters in each direction paral-

par-

allel nerve fibers

molecular layer that the dendrites of the Purkinje cells

synapse with each Purkinje cell.

different from the climbing fiber input because their

of mossy fibers must be stimulated simultaneously to

usually takes the form of a much weaker short-

duration Purkinje cell action potential called a simple

spike

potential caused by climbing fiber input.

Purkinje Cells and Deep Nuclear Cells Fire Continuously Under

Normal Resting Conditions.

One characteristic of both

Purkinje cells and deep nuclear cells is that normally

modulated upward or downward.

Balance Between Excitation and Inhibition at the Deep Cere-

bellar Nuclei.

deep nuclear cells by both the climbing and the mossy

between these two effects is slightly in favor of exci-

deep nuclear cell remains relatively constant at a mod-

erate level of continuous stimulation.

initiating signal from the cerebral motor cortex or

brain stem at first greatly increases deep nuclear

feedback inhibitory signals from the Purkinje cell

tory signal sent by the deep nuclear cells into the

motor output pathway to enhance the motor move-

signal of the type that is effective in providing

damping

a negative feedback signal occurs after a short delay

to stop the muscle movement from overshooting its

In addition to the

other types of neurons are located in the cerebellum:

basket cells and stellate cells

cells are located in the molecular layer of the cerebel-

lateral

inhibition

the signal in the same manner that lateral inhibition

sharpens contrast of signals in many other neuronal

circuits of the nervous system.

provide rapid turn-on signals for the agonist muscles

and simultaneous reciprocal turn-off signals for the

cerebellum is mainly responsible for timing and exe-

cuting the turn-off signals to the agonists and turn-on

Purkinje

cell

Climbing

fiber

Deep

nuclear

cell

Input

(inferior olive)

Output

Excitation

Inhibition

Granule

cells

Cortex

Input

(all other afferents)

Mossy

fiber

Molecular

layer

Purkinje

cell layer

Granule

cell layer

Deep

nuclei

bellar cortex with its three layers.

the physical relationship of the deep cerebellar nuclei to the cere-

cell (an inhibitory neuron) shown in black. To the right is shown

cerebellum, with excitatory neurons shown in red and the Purkinje

The left side of this figure shows the basic neuronal circuit of the

Figure 56–7

. This consists principally

1. The

motor control functions at three levels, as follows:

The nervous system uses the cerebellum to coordinate

Function of the Cerebellum in Overall

cerebellum to cause further change.

fibers no longer need to send “error” signals to the

perfection. When this has been achieved, the climbing

cerebellum, is believed to make the timing and other

along with other possible “learning” functions of the

cells. Over a period of time, this change in sensitivity,

the intended movement. And the climbing fiber signals

for the first time, feedback signals from the muscle and

ing spikes. When a person performs a new movement

During this time, the Purkinje cell fires with one initial

tree of the Purkinje cell, lasting for up to a second.

about once per second. But each time they do fire, they

Under resting conditions, the climbing fibers fire

granule cell excitation becomes altered. Furthermore,

sively adapt during the training process. Especially,

answer is not known, although it is known that sensi-

How do these adjustments come about? The exact

other times requiring hundreds of movements.

ments before the desired result is achieved, but at

more precise, sometimes requiring only a few move-

times, the individual events become progressively

movement. But after the act has been performed many

the end of contraction, and the timing of these are

at the onset of contraction, the degree or inhibition at

ically, when a person first performs a new motor act,

contractions, must be learned by the cerebellum. Typ-

and offset of muscle contractions, as well as timing of

The degree to which the cerebellum supports onset

Errors—Role of the Climbing Fibers

The Purkinje Cells “Learn” to Correct Motor

antagonist muscles, and controlling the timing as well.

on and turn-off signals, controlling the agonist and

They are presented here especially to illustrate ways

are still to be determined; they, too, could play roles in

besides Purkinje cells. The functions of some of these

muscles. But we must remember, too, that the cere-

ment, mirroring whatever occurs in the agonist

the cord can initiate. Therefore, these circuits are part

nist muscles. Most important, remember that through-

Thus, one can see how the complete cerebellar

time.

fore, this helps

that had originally turned on the movement. There-

But once the Purkinje cell is excited, it in turn sends a

have diameters of only a fraction of a millimeter. Also,

fibers of the cerebellar cortical molecular layer, which

nerve fibers in the nervous system: that is, the parallel

through some of the smallest, slowest-conducting

the deep nuclear cells. This pathway passes

fibers, to the Purkinje cells. The Purkinje cells in turn

cerebellar cortex and eventually, by way of “parallel”

Now, what causes the turn-off signal for the agonist

missing. This cerebellar support makes the turn-on

cerebellum, the secondary extra supportive signal is

when the cerebellum is intact, but in the absence of the

and the cerebellar signals. This is the normal effect

sequence, the turn-on signal, after a few milliseconds,

already been begun by the cerebral cortex. As a con-

stem, to support the muscle contraction signal that had

into the cerebral corticospinal motor system, either by

nuclei; this instantly sends an excitatory signal back

the pontile mossy fibers into the cerebellum. One

At the same time, parallel signals are sent by way of

These signals pass through noncerebellar brain stem

as follows.

cerebellar circuit of Figure 56–7 how this might work,

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

703

Let us suppose that the turn-on/turn-off pattern of

agonist/antagonist contraction at the onset of move-

ment begins with signals from the cerebral cortex.

and cord pathways directly to the agonist muscle to

begin the initial contraction.

branch of each mossy fiber goes directly to deep

nuclear cells in the dentate or other deep cerebellar

way of return signals through the thalamus to the cere-

bral cortex or by way of neuronal circuitry in the brain

becomes even more powerful than it was at the start

because it becomes the sum of both the cortical

muscle contraction much stronger than it would be if

the cerebellum did not exist.

muscles at the termination of the movement? Remem-

ber that all mossy fibers have a second branch that

transmits signals by way of the granule cells to the

inhibit

the signals from these fibers are weak so that they

require a finite period of time to build up enough exci-

tation in the dendrites of the Purkinje cell to excite it.

strong inhibitory signal to the same deep nuclear cell

to turn off the movement after a short

circuit could cause a rapid turn-on agonist muscle con-

traction at the beginning of a movement and yet cause

also a precisely timed turn-off of the same agonist con-

traction after a given time period.

Now let us speculate on the circuit for the antago-

out the spinal cord there are reciprocal agonist/

antagonist circuits for virtually every movement that

of the basis for antagonist turn-off at the onset of

movement and then turn-on at termination of move-

bellum contains several other types of inhibitory cells

the initial inhibition of the antagonist muscles at onset

of a movement and subsequent excitation at the end

of a movement.

All these mechanisms are still partly speculation.

by which the cerebellum could cause exaggerated turn-

the degree of motor enhancement by the cerebellum

almost always incorrect for precise performance of the

tivity levels of cerebellar circuits themselves progres-

the sensitivity of the Purkinje cells to respond to the

this sensitivity change is brought about by signals from

the climbing fibers entering the cerebellum from the

inferior olivary complex.

cause extreme depolarization of the entire dendritic

strong output spike followed by a series of diminish-

joint proprioceptors will usually denote to the cere-

bellum how much the actual movement fails to match

in some way alter long-term sensitivity of the Purkinje

aspects of cerebellar control of movements approach

Motor Control

vestibulocerebellum

of the small flocculonodular cerebellar lobes (that

fractions of a second, and (2) feedback information

intended sequential plan of movement

the midbrain red nucleus, telling the cerebellum the

information when a movement is performed: (1) infor-

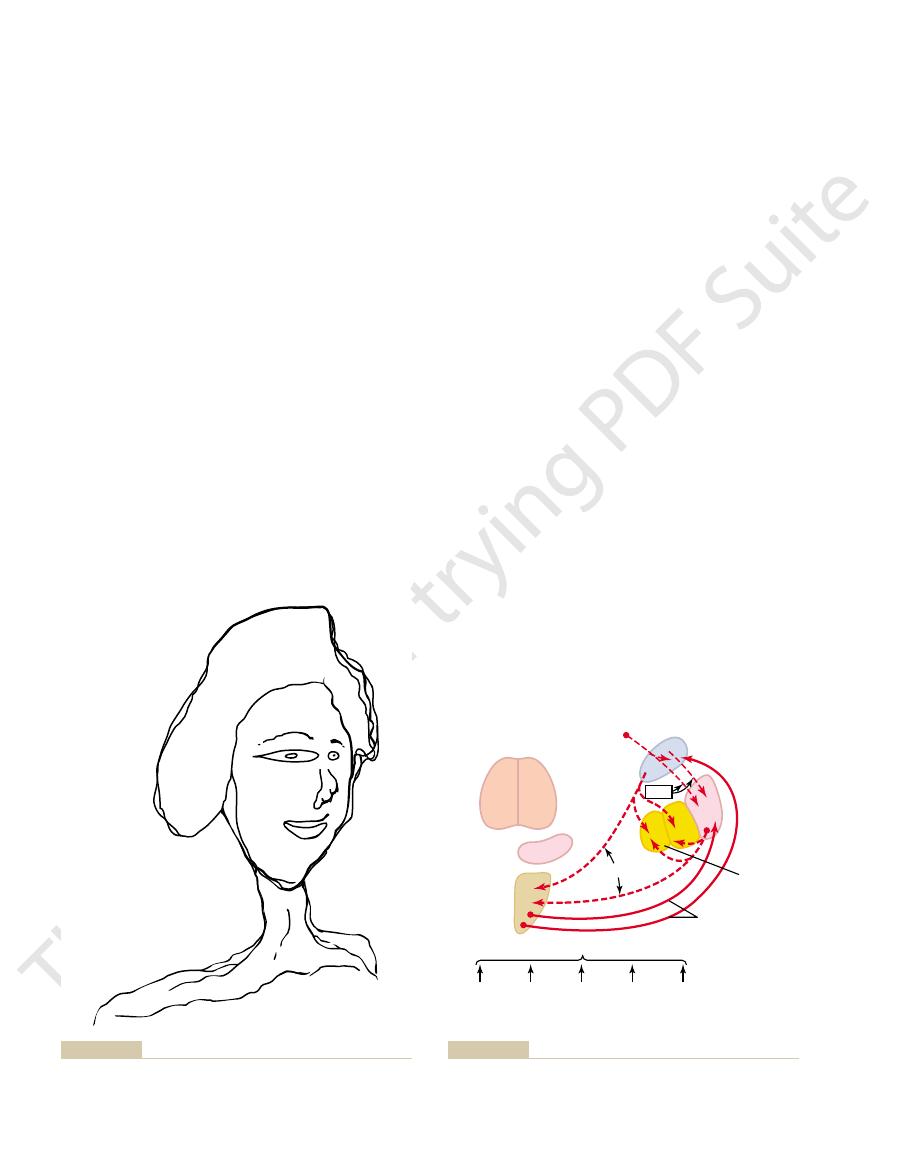

As shown in Figure 56–8, the intermediate zone of

Cerebellar Cortex and the Interposed Nucleus

Limb Movements by Way of the Intermediate

Spinocerebellum—Feedback Control of Distal

librium even during extremely rapid motion, including

Thus, during control of equilibrium, it is presumed

brain’s progression to the next sequential movement.

The results of these calculations are the key to the

different parts will be during the next few milliseconds.

directions the body parts are moving. It is then the

performed rapidly? The answer is that the signals from

sequential act, especially when the movements are

occur. How, then, is it possible for the brain to know

time. Therefore, it is never possible for return signals

15 to 20 milliseconds. The feet of a person running

to 120 m/sec in the spinocerebellar afferent tracts, the

most rapidly conducting sensory pathways are used, up

ferent parts of the body to the brain. Even when the

the vestibular apparatus.

rapid changes

muscle contractions of the spine, hips, and shoulders

late the semicircular ducts. This suggests that the

changes in direction

during stasis, especially so when these movements

cerebellar dysfunction, equilibrium is far more dis-

stem? A clue is the fact that in people with vestibulo-

We still must ask the question, what role does the

movements.

which constitute the vestibulocerebellum, causes

in Chapter 55, loss of the flocculonodular lobes and

in the inner ear developed. Furthermore, as discussed

The vestibulocerebellum originated phylogenetically

Spinal Cord to Control Equilibrium and

Vestibulocerebellum—Its Function in

development of “motor imagery” of movements

advance of the actual movements. This is called

sequential voluntary body and limb movements,

the cerebrum. It transmits its output information

to the intermediate zones. It receives virtually all

lateral zones of the cerebellar hemispheres, lateral

. This consists of the large

3. The

fingers.

portions of the limbs, especially the hands and

sides of the vermis. It provides the circuitry for

. This consists of most of the

2. The

for most of the body’s equilibrium movements.

portions of the vermis. It provides neural circuits

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

704

Unit XI

lie under the posterior cerebellum) and adjacent

spinocerebellum

vermis of the posterior and anterior cerebellum

plus the adjacent intermediate zones on both

coordinating mainly movements of the distal

cerebrocerebellum

its input from the cerebral motor cortex and

adjacent premotor and somatosensory cortices of

in the upward direction back to the brain,

functioning in a feedback manner with the

cerebral cortical sensorimotor system to plan

planning these as much as tenths of a second in

to be performed.

Association with the Brain Stem and

Postural Movements

at about the same time that the vestibular apparatus

adjacent portions of the vermis of the cerebellum,

extreme disturbance of equilibrium and postural

vestibulocerebellum play in equilibrium that cannot

be provided by other neuronal machinery of the brain

turbed during performance of rapid motions than

involve

of movement and stimu-

vestibulocerebellum is especially important in con-

trolling balance between agonist and antagonist

during

in body positions as required by

One of the major problems in controlling balance is

the amount of time required to transmit position

signals and velocity of movement signals from the dif-

delay for transmission from the feet to the brain is still

rapidly can move as much as 10 inches during that

from the peripheral parts of the body to reach the

brain at the same time that the movements actually

when to stop a movement and to perform the next

the periphery tell the brain how rapidly and in which

function of the vestibulocerebellum to calculate in

advance from these rates and directions where the

that information from both the body periphery and the

vestibular apparatus is used in a typical feedback

control circuit to provide anticipatory correction of

postural motor signals necessary for maintaining equi-

rapidly changing directions of motion.

each cerebellar hemisphere receives two types of

mation from the cerebral motor cortex and from

for the next few

Motor cortex

Thalamus

Muscles

Red nucleus

Intermediate

zone of

cerebellum

Spinocerebellar

tract

Mesencephalon,

pons, and medulla

Corticospinal tract

Reticulospinal

and rubrospinal

tracts

especially the intermediate zone of the cerebellum.

Cerebral and cerebellar control of voluntary movements, involving

Figure 56–8

complex purposeful movements of the hands, fingers,

dentate nuclei, can lead to extreme incoordination of

bellar hemispheres along with their deep nuclei, the

Even so, destruction of the lateral zones of the cere-

the peripheral parts of the body. Also, almost all com-

speak. Yet the large lateral zones of the cerebellar

ment, especially with the hands and fingers, and to

enlarged. This goes along with human abilities to plan

In human beings, the lateral zones of the two cerebel-

Hemisphere to Plan, Sequence, and Time

Large Lateral Zone of the Cerebellar

Cerebrocerebellum—Function of the

for preplanned rapid ballistic movements. One also

fully organized to perform this biphasic, first excitatory

bellum as described earlier, one sees that it is beauti-

movement off. Thus, the automatism of ballistic move-

of the cerebellar circuit, the motor cortex has to think

beyond the intended mark. Therefore, in the absence

turn off, usually allowing the movement to go well

developed is weak, and (3) the movements are slow to

that the cerebellum usually provides, (2) the force

Three major changes occur: (1) The movements are

in a car.

ments of the eyes, in which the eyes jump from one

stop.Another important example is the saccadic move-

ballistic movements

over. These movements are called

fingers in typing, occur so rapidly that it is not possi-

movements of the body, such as the movements of the

control by the nervous system, the cerebellum pro-

damping circuits built into the mechanisms. For motor

This is the basic characteristic

as well as the tremor.

the intended point, thereby preventing the overshoot

But, if the cerebellum is intact, appropriate learned,

, or

on its mark. This effect is called an

intended point for several cycles before it finally fixes

tuted. Thus, the arm oscillates back and forth past its

tum, overshoots once more in the opposite direction,

intended position. But the arm, by virtue of its momen-

destroyed, the conscious centers of the cerebrum even-

. If overshooting

overshoot

ments have a tendency to

stopped. Because of momentum, all pendular move-

moved, momentum develops, and the momentum

body are “pendular.” For instance, when an arm is

ably, the olivary-Purkinje cell system along with pos-

olivary complex; if the signals do not compare favor-

dorsal spinocerebellar tract. We learned earlier that

ceptor sensory organs, transmitted principally in the

neurons, and this, too, is integrated with the signals

to the cerebellum an “efference” copy of the actual

back to the cerebellum from the periphery. In fact,

by the respective parts of the body, as transmitted

corticopontocerebellar tract, with the “performance”

higher levels of the motor control system, as transmit-

cerebellum seems to compare the “intentions” of the

forming acute purposeful patterned movements. The

vides smooth, coordinate movements of the agonist

This part of the cerebellar motor control system pro-

of the limbs, particularly the hands and fingers.

gray matter, the neurons that control the distal parts

The rubrospinal tract in turn joins

magnocellular portion

movements, the deep nuclear cells of the interposed

actual movements

the distal proprioceptors of the limbs, telling the cere-

from the peripheral parts of the body, especially from

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

705

bellum what

result.

After the intermediate zone of the cerebellum has

compared the intended movements with the actual

nucleus send corrective output signals (1) back to the

cerebral motor cortex through relay nuclei in the thal-

amus and (2) to the

(the lower

portion) of the red nucleus that gives rise to the

rubrospinal tract.

the corticospinal tract in innervating the lateral most

motor neurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord

and antagonist muscles of the distal limbs for per-

ted to the intermediate cerebellar zone through the

the ventral spinocerebellar tract even transmits back

motor control signals that reach the anterior motor

arriving from the muscle spindles and other proprio-

similar comparator signals also go to the inferior

sibly other cerebellar learning mechanisms eventually

corrects the motions until they perform the desired

function.

Function of the Cerebellum to Prevent Overshoot of Movements

and to “Damp” Movements.

Almost all movements of the

must be overcome before the movement can be

does occur in a person whose cerebellum has been

tually recognize this and initiate a movement in the

reverse direction attempting to bring the arm to its

and appropriate corrective signals must again be insti-

action tremor

intention tremor.

subconscious signals stop the movement precisely at

of a damping system. All control systems regulating

pendular elements that have inertia must have

vides most of this damping function.

Cerebellar Control of Ballistic Movements.

Most rapid

ble to receive feedback information either from the

periphery to the cerebellum or from the cerebellum

back to the motor cortex before the movements are

,

meaning that the entire movement is preplanned and

set into motion to go a specific distance and then to

position to the next when reading or when looking at

successive points along a road as a person is moving

Much can be understood about the function of the

cerebellum by studying the changes that occur in these

ballistic movements when the cerebellum is removed.

slow to develop and do not have the extra onset surge

extra hard to turn ballistic movements on and again

has to think hard and take extra time to turn the

ments is lost.

If one considers once again the circuitry of the cere-

and then delayed inhibitory function that is required

sees that the built-in timing circuits of the cerebellar

cortex are fundamental to this particular ability of the

cerebellum.

Complex Movements

lar hemispheres are highly developed and greatly

and perform intricate sequential patterns of move-

hemispheres have no direct input of information from

munication between these lateral cerebellar areas and

the cerebral cortex is not with the primary cerebral

motor cortex itself but instead with the premotor area

and primary and association somatosensory areas.

begun; if the cerebellum is not available to do this, the

beyond the point of intention. This results from the

of the cerebellum, a person ordinarily moves the hand

Past pointing

pensatory movement.This effect is called

predict how far movements will go. Therefore, the

lum, the subconscious motor control system cannot

pointed out previously, in the absence of the cerebel-

Two of the most important symp-

, or

tion of the cerebellum, the cerebellar lesion usually

Therefore, to cause serious and continuing dysfunc-

. Thus, the remaining portions of the motor

slowly

as long as the animal performs all movements

bellar nuclei are not removed along with the cortex, the

side of the brain has been removed, if the deep cere-

ties in motor function. In fact, several months after as

Clinical Abnormalities of

rapidly changing

can be compared; it is often stated that the cerebellum

base,” perhaps using time-delay circuits, against which

is quite possible that the cerebellum provides a “time-

extramotor predictive functions of the cerebellum. It

We are only now beginning to learn about these

tions of the cerebellum in monkeys. Such a monkey

approaching an object. A striking experiment that

pation. As an example, a person can predict from

the brain, but both of these require cerebellar partici-

body. For instance, the rates of progression of both

helps to “time” events other than movements of the

The cerebrocerebellum (the large lateral lobes) also

smooth progression of movements

required for writing, running, or even talking) to

too late. Therefore, lesions in the lateral zones of the

ceeding movement may begin too early or, more likely,

tial movement needs to begin. As a result, the suc-

given time. Without this timing capability, the person

ment. In the absence of these cerebellar zones, one

Timing Function.

disturbed for rapid movements.

the cerebellar hemispheres, this capability is seriously

succession. In the absence of the large lateral zones of

of normal motor function is one’s ability to progress

To summarize, one of the most important features

seconds later.

movement

present movement is still occurring. Thus, the lateral

between cerebellum and cerebral cortex, appropriate

lar hemispheres. Then, amid much two-way traffic

tor areas of the cerebral cortex, and from there the

basal ganglia. It seems that the “plan” of sequential

The planning of

movements.

tial movements and (2) the “timing” of the sequential

aspects of motor control: (1) the planning of sequen-

the primary motor cortex. However, experimental

and feet and of the speech apparatus. This has been

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

706

Unit XI

difficult to understand because of lack of direct com-

munication between this part of the cerebellum and

studies suggest that these portions of the cerebellum

are concerned with two other important but indirect

Planning of Sequential Movements.

sequential movements requires that the lateral zones

of the hemispheres communicate with both the pre-

motor and the sensory portions of the cerebral cortex,

and it requires two-way communication between these

cerebral cortex areas with corresponding areas of the

movements actually begins in the sensory and premo-

plan is transmitted to the lateral zones of the cerebel-

motor signals provide transition from one sequence of

movements to the next.

An exceedingly interesting observation that sup-

ports this view is that many neurons in the cerebellar

dentate nuclei display the activity pattern for the

sequential movement that is yet to come while the

cerebellar zones appear to be involved not with what

movement is happening at a given moment but with

what will be happening during the next sequential

a fraction of a second or perhaps even

smoothly from one movement to the next in orderly

Another important function of the

lateral zones of the cerebellar hemispheres is to

provide appropriate timing for each succeeding move-

loses the subconscious ability to predict ahead of time

how far the different parts of the body will move in a

becomes unable to determine when the next sequen-

cerebellum cause complex movements (such as those

become incoordinate and lacking ability to progress in

orderly sequence from one movement to the next.

Such cerebellar lesions are said to cause failure of

.

Extramotor Predictive Functions of the Cerebrocerebellum.

auditory and visual phenomena can be predicted by

the changing visual scene how rapidly he or she is

demonstrates the importance of the cerebellum in this

ability is the effects of removing the large lateral por-

occasionally charges the wall of a corridor and literally

bashes its brains because it is unable to predict when

it will reach the wall.

signals from other parts of the central nervous system

is particularly helpful in interpreting

spatiotemporal relations in sensory information.

the Cerebellum

An important feature of clinical cerebellar abnormali-

ties is that destruction of small portions of the lateral

cerebellar cortex seldom causes detectable abnormali-

much as one half of the lateral cerebellar cortex on one

motor functions of the animal appear to be almost

normal

control system are capable of compensating tremen-

dously for loss of parts of the cerebellum.

must involve one or more of the deep cerebellar

nuclei—the dentate, interposed

fastigial nuclei.

Dysmetria and Ataxia.

toms of cerebellar disease are dysmetria and ataxia. As

movements ordinarily overshoot their intended mark;

then the conscious portion of the brain overcompen-

sates in the opposite direction for the succeeding com-

dysmetria, and

it results in uncoordinated movements that are called

ataxia. Dysmetria and ataxia can also result from lesions

in the spinocerebellar tracts because feedback informa-

tion from the moving parts of the body to the cerebel-

lum is essential for cerebellar timing of movement

termination.

Past Pointing.

means that in the absence

or some other moving part of the body considerably

fact that normally the cerebellum initiates most of the

motor signal that turns off a movement after it is

movement ordinarily goes beyond the intended mark.

hemispheres. Note also that almost all motor and

lateral to and surrounding the thalamus, occupying a

. They are located mainly

side of the brain, these ganglia consist of the

basal ganglia to other structures of the brain. On each

Figure 56–9 shows the anatomical relations of the

cortex and corticospinal motor control system. In fact,

The basal ganglia, like the cerebellum, constitute

the side of the cerebellar lesion. The hypotonia results

larly of the dentate and interposed nuclei, causes

Loss of the deep cerebellar nuclei, particu-

lar cerebellum from the semicircular ducts.

lar lobes of the cerebellum are damaged; in this instance

cerebellum. It occurs especially when the flocculonodu-

movements of the eyes rather than steady fixation, and

off-center type of fixation results in rapid, tremulous

fixate the eyes on a scene to one side of the head. This

motor movements.

ing and failure of the cerebellar system to “damp” the

action tremor,

mark. This reaction is called an

mark, first overshooting the mark and then vibrating

to oscillate, especially when they approach the intended

bellum performs a voluntary act, the movements tend

When a person who has lost the cere-

Intention Tremor.

ble. This is called

intervals, and resultant speech that is often unintelligi-

weak, some held for long intervals, some held for short

jumbled vocalization, with some syllables loud, some

piratory system. Lack of coordination among these and

vidual muscle movements in the larynx, mouth, and res-

dysdiadochokine-

and downward motions. This is called

result, a series of stalled attempted but jumbled move-

the hand during any portion of the movement. As a

“loses” all perception of the instantaneous position of

and downward at a rapid rate. The patient rapidly

can occur. One can demonstrate this readily by having

too late, so that no orderly “progression of movement”

during rapid motor movements. As a result, the suc-

be at a given time, it “loses” perception of the parts

When the motor control system

Therefore, past pointing is actually a manifestation of

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

707

dysmetria.

Failure of Progression

Dysdiadochokinesia.

fails to predict where the different parts of the body will

ceeding movement may begin much too early or much

a patient with cerebellar damage turn one hand upward

ments occurs instead of the normal coordinate upward

sia.

Dysarthria.

Another example in which failure of pro-

gression occurs is in talking because the formation of

words depends on rapid and orderly succession of indi-

inability to adjust in advance either the intensity of

sound or duration of each successive sound causes

dysarthria.

back and forth several times before settling on the

intention tremor or an

and it results from cerebellar overshoot-

Cerebellar Nystagmus.

Cerebellar nystagmus is tremor of

the eyeballs that occurs usually when one attempts to

it is another manifestation of failure of damping by the

it is also associated with loss of equilibrium because of

dysfunction of the pathways through the flocculonodu-

Hypotonia.

decreased tone of the peripheral body musculature on

from loss of cerebellar facilitation of the motor cortex

and brain stem motor nuclei by tonic signals from the

deep cerebellar nuclei.

Basal Ganglia—Their Motor

Functions

another accessory motor system that functions usually

not by itself but in close association with the cerebral

the basal ganglia receive most of their input signals

from the cerebral cortex itself and also return almost

all their output signals back to the cortex.

caudate

nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, substantia nigra,

and subthalamic nucleus

large portion of the interior regions of both cerebral

Longitudinal fissure

Caudate nucleus

Tail of caudate

LATERAL

Fibers to and from

spinal cord in

internal capsule

Putamen and

globus pallidus

POSTERIOR

ANTERIOR

Thalamus

and Physiology. Philadelphia: WB

AC: Basic Neuroscience: Anatomy

sional view. (Redrawn from Guyton

thalamus, shown in three-dimen-

ganglia to the cerebral cortex and

Anatomical relations of the basal

Figure 56–9

Saunders Co, 1992.)

primary motor cortex. Thus,

the thalamus, and finally return to the cerebral primary

to the internal portion of the globus pallidus, next to

putamen (mainly bypassing the caudate nucleus), then

areas of the sensory cortex. Next they pass to the

They begin mainly in the premotor and supplementary

Figure 56–11

most of them performed subconsciously.

eyes, and virtually any other of our skilled movements,

aspects of vocalization, controlled movements of the

ing a baseball, the movements of shoveling dirt, most

a basketball through a hoop, passing a football, throw-

cutting paper with scissors, hammering nails, shooting

time how to write.

becomes crude, as if one were learning for the first

longer provide these patterns. Instead, one’s writing

ganglia, the cortical system of motor control can no

alphabet. When there is serious damage to the basal

. An example is the writing of letters of the

Executing Patterns of Motor Activity—

Function of the Basal Ganglia in

cially on two major circuits, the

basal ganglia.

cuitry of the basal ganglia system, showing the tremen-

and cerebellar circuitry. To the right is the major cir-

the motor cortex, thalamus, and associated brain stem

complex, as shown in Figure 56–10. To the left is shown

The anatomical

Neuronal Circuitry of the Basal Ganglia.

of the brain. It is important for our

. This space is called

between the major masses of the basal ganglia, the

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

708

Unit XI

sensory nerve fibers connecting the cerebral cortex

and spinal cord pass through the space that lies

caudate nucleus and the putamen

the internal capsule

current discussion because of the intimate association

between the basal ganglia and the corticospinal system

for motor control.

connections between the basal ganglia and the other

brain elements that provide motor control are

dous interconnections among the basal ganglia

themselves plus extensive input and output pathways

between the other motor regions of the brain and the

In the next few sections we will concentrate espe-

putamen circuit and the

caudate circuit.

The Putamen Circuit

One of the principal roles of the basal ganglia in motor

control is to function in association with the corti-

cospinal system to control complex patterns of motor

activity

Other patterns that require the basal ganglia are

Neural Pathways of the Putamen Circuit.

shows the principal pathways through the basal

ganglia for executing learned patterns of movement.

areas of the motor cortex and in the somatosensory

the ventroanterior and ventrolateral relay nuclei of

motor cortex and to portions of the premotor and sup-

plementary cerebral areas closely associated with the

the putamen circuit has its

Motor cortex

Thalamus

Muscles

Globus

pallidus

Inferior olive

Reticular formation

Cerebellum

Putamen

Caudate

nucleus

Premotor and

supplemental motor

association areas

Subthalamus

Substantia nigra

Red nucleus

cerebellar system for movement control.

Relation of the basal ganglial circuitry to the corticospinal-

Figure 56–10

Caudate

Subthalamus

Substantia nigra

Premotor and

supplemental Primary motor

Prefrontal

Ventroanterior and

ventrolateral

nuclei of thalamus

Putamen

Globus

pallidus

internal/external

Somatosensory

cution of learned patterns of movement.

Putamen circuit through the basal ganglia for subconscious exe-

Figure 56–11

write a small “a” on a piece of paper or a large “a” on

the letter “a” slowly or rapidly. Also, he or she may

the movement will be. For instance, a person may write

Two important capabilities of the brain in controlling

Intensity of Movements

Change the Timing and to Scale the

Function of the Basal Ganglia to

a complex goal that might itself last for many seconds.

determines subconsciously, and within seconds, which

appropriately. Thus, cognitive control of motor activity

thinking for too long a time, to respond quickly and

might not have the instinctive knowledge, without

a tree. Without the cognitive functions, the person

(2) beginning to run, and (3) even attempting to climb

ual muscle movements.

primary motor cortex. Instead, the returning signals go

motor areas of the cerebral cortex, but with almost

back to the prefrontal, premotor, and supplementary

ventroanterior and ventrolateral thalamus, and finally

internal globus pallidus, then to the relay nuclei of the

the caudate nucleus, they are next transmitted to the

patterns.

of the cerebral cortex overlying the caudate nucleus,

poral lobes. Furthermore, the caudate nucleus receives

curving forward again like the letter “C” into the tem-

through the parietal and occipital lobes, and finally

riorly in the frontal lobes, then passing posteriorly

extends into all lobes of the cerebrum, beginning ante-

is that the caudate nucleus, as shown in Figure 56–9,

those of the putamen circuit. Part of the reason for this

shown in Figure 56–12, are somewhat different from

The neural connections between the caudate

role in this cognitive control of motor activity.

. The caudate nucleus plays a major

erated in the mind, a process called

information already stored in memory. Most of our

the brain, using both sensory input to the brain plus

The term

Cognitive Control of Sequences of

Role of the Basal Ganglia for

discuss in more detail later.

, which we

Parkinson

, and

chorea

the body, called

in the hands, face, and other parts of

ing movements

flick-

of an entire limb, a condition called

flailing movements

athetosis.

a hand, an arm, the neck, or the face—movements

writhing movements

movement become severely abnormal. For instance,

the circuit is damaged or blocked, certain patterns of

answer is poorly known. However, when a portion of

tion to help execute patterns of movement? The

to the motor cortex by way of the thalamus.

thalamus, and the substantia nigra—finally returning

putamen through the external globus pallidus, the sub-

cortex. Func-

primary motor cortex itself. Then its outputs do go

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

709

inputs mainly from those parts of the brain adjacent to

the primary motor cortex but not much from the

mainly back to the primary motor cortex or closely

associated premotor and supplementary

tioning in close association with this primary putamen

circuit are ancillary circuits that pass from the

Abnormal Function in the Putamen Circuit: Athetosis, Hemibal-

lismus, and Chorea.

How does the putamen circuit func-

lesions in the globus pallidus frequently lead to spon-

taneous and often continuous

of

called

A lesion in the subthalamus often leads to sudden

hemiballismus.

Multiple small lesions in the putamen lead to

.

Lesions of the substantia nigra lead to the common

and extremely severe disease of rigidity, akinesia

tremors known as

’s disease

Motor Patterns—The Caudate Circuit

cognition means the thinking processes of

motor actions occur as a consequence of thoughts gen-

cognitive control

of motor activity

nucleus and the corticospinal motor control system,

large amounts of its input from the association areas

mainly areas that also integrate the different types of

sensory and motor information into usable thought

After the signals pass from the cerebral cortex to

none of the returning signals passing directly to the

to those accessory motor regions in the premotor and

supplementary motor areas that are concerned with

putting together sequential patterns of movement

lasting 5 or more seconds instead of exciting individ-

A good example of this would be a person seeing a

lion approach and then responding instantaneously

and automatically by (1) turning away from the lion,

patterns of movement will be used together to achieve

movement are (1) to determine how rapidly the move-

ment is to be performed and (2) to control how large

Caudate

Subthalamus

Substantia nigra

Premotor and

supplemental Primary motor

Prefrontal

Ventroanterior and

ventrolateral

nuclei of thalamus

Putamen

Globus

pallidus

internal/external

Somatosensory

of sequential and parallel motor patterns to achieve specific con-

Caudate circuit through the basal ganglia for cognitive planning

Figure 56–12

scious goals.

inhibitory agent. Therefore, GABA neurons in the

the neurotransmitter GABA always functions as an

For the present, it should be remembered that

we discuss behavior, sleep, wakefulness, and functions

basal ganglia, as well as in subsequent chapters when

inhibitory transmitters. We will have more to say about

especially by the dopamine, GABA, and serotonin

tamate pathways

the cerebrum. In addition to all these are

, and several other neurotrans-

nucleus and putamen, and (4) multiple general path-

choline

the globus pallidus and substantia nigra, (3)

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

and putamen, (2)

within the basal ganglia, showing (1)

Figure 56–14 demonstrates the interplay of several

Functions of Specific

circuit. However, our understanding of function in the

her right body for the performance of tasks, almost not

or her right arm, right hand, or other portions of his or

Also, such a person will try always to avoid using his

another human being, providing proper proportions

Figure 56–13 shows the way in which a person lacking

tion of the body and its parts to all its surroundings.

association with the cerebral cortex. One especially

ganglia do not function alone; they function in close

sometimes they are nonexistent. Here again, the basal

these timing and scaling functions are poor; in fact,

same.

a chalkboard. Regardless of the choice, the propor-

The Nervous System: C. Motor and Integrative Neurophysiology

710

Unit XI

tional characteristics of the letter remain nearly the

In patients with severe lesions of the basal ganglia,

important cortical area is the posterior parietal cortex,

which is the locus of the spatial coordinates for motor

control of all parts of the body as well as for the rela-

a left posterior parietal cortex might draw the face of

for the right side of the face but almost ignoring the

left side (which is in his or her right field of vision).

knowing that these parts of his or her body exist.

Because the caudate circuit of the basal ganglial

system functions mainly with association areas of the

cerebral cortex such as the posterior parietal cortex,

presumably the timing and scaling of movements are

functions of this caudate cognitive motor control

basal ganglia is still so imprecise that much of what is

conjectured in the last few sections is analytical deduc-

tion rather than proven fact.

Neurotransmitter Substances in the

Basal Ganglial System

specific neurotransmitters that are known to function

dopamine path-

ways from the substantia nigra to the caudate nucleus

pathways from the caudate nucleus and putamen to

acetyl-

pathways from the cortex to the caudate

ways from the brain stem that secrete norepinephrine,

serotonin, enkephalin

mitters in the basal ganglia as well as in other parts of

multiple glu-

that provide most of the excitatory

signals (not shown in the figure) that balance out

the large numbers of inhibitory signals transmitted

some of these neurotransmitter and hormonal systems

in subsequent sections when we discuss diseases of the

of the autonomic nervous system.

feedback loops from the cortex through the basal

nates of the right field of vision are stored.

damage in his or her left parietal cortex where the spatial coordi-

Typical drawing that might be made by a person who has severe

Figure 56–13

Caudate nucleus

From cortex

From brain stem

Substantia

nigra

1. Norepinephrine

2. Serotonin

3. Enkephalin

Putamen

Globus

pallidus

Dopamine

GABA

Ach

Neuronal pathways that secrete different types of neurotransmit-

Figure 56–14

ter substances in the basal ganglia. Ach, acetylcholine; GABA,

gamma-aminobutyric acid.

loss of acetylcholine-secreting neurons, perhaps espe-

not result from the loss of GABA neurons but from the

The dementia in Huntington’s disease probably does

the distortional movements.

globus pallidus and substantia nigra. This loss of inhibi-

of the GABA neurons normally inhibit portions of the

neurons in many parts of the brain. The axon terminals

bodies of the GABA-secreting neurons in the caudate

The abnormal movements of Huntington’s disease

dementia develops along with the motor dysfunctions.

movements of the entire body. In addition, severe

usually begins causing symptoms at age 30 to 40 years.

Huntington’s disease is a hereditary disorder that

Huntington’s Disease (Huntington’s Chorea)

results.

amus have been used, sometimes with surprisingly good

with Parkinson’s disease, lesions placed in the subthal-

sometimes serious neurological damage. In monkeys

rior nuclei of the thalamus, which blocked part of the

these signals surgically. For a number of years, surgical

abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease, multiple attempts

in the Basal Ganglia.

Treatment by Destroying Part of the Feedback Circuitry

would become the treatment of the future.

months. If persistence could be achieved, perhaps this

However, the cells do not live for more than a few

short-term success to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Transplantation of dopamine-secreting cells (cells

Treatment with Transplanted Fetal Dopamine Cells.

of one of these drugs alone.

neurons in the substantia nigra. Therefore, appropriate

In addition, for reasons not understood, this treatment

remains in the basal ganglial tissues for a longer time.

secreted. Therefore, any dopamine that is released

inhibits monoamine oxidase, which is responsible for

-deprenyl. This drug

Parkinson’s disease is the drug

Treatment with l-Deprenyl.

-dopa does allow it to pass.

brain barrier, even though the slightly different struc-

putamen. Administration of dopamine itself does not

-dopa is converted in the brain into dopamine, and the

and akinesia. The reason for this is believed to be that

liorates many of the symptoms, especially the rigidity

to patients with Parkinson’s disease usually ame-

Treatment with l-Dopa.

drive for motor activity so greatly that akinesia results.

decreased along with its decrease in the basal ganglia. It

, is often

system, especially in the

ulative. However, dopamine secretion in the limbic

instead of smooth. The cause of this akinesia is still spec-

occur, they are usually stiff and staccato in character

the patient’s willpower. Then, when the movements do

The mental effort, even mental anguish, that is necessary

even the simplest movement in severe parkinsonism, the

toms of muscle rigidity and tremor, because to perform

that occurs in Parkinson’s disease is often

The

intention tremor.

bellar tremor, which occurs only when the person per-

, in contradistinction to cere-

of Parkinson’s disease. This

bition, leading to the

rigidity.

many or all of the muscles of the body, thus leading to

control system. These signals could overly excite

ter; therefore, destruction of the dopaminergic neurons

unknown. However, the dopamine secreted in the

The causes of these abnormal motor effects are

second, and (3) serious difficulty in initiating movement,

person is resting at a fixed rate of 3 to 6 cycles per

ity of much of the musculature of the body, (2) invol-

and putamen. The disease is characterized by (1) rigid-

Parkinson’s disease, known also as

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.

eases result from damage in the basal ganglia. These are

globus pallidus and subthalamus, two other major dis-

, which have

under some conditions.

so that it, too, undoubtedly functions as a stabilizer

motor control systems. Dopamine also functions as an

positive feedback loops, thus lending stability to the

, rather than

negative feedback loops

Chapter 56

Contributions of the Cerebellum and Basal Ganglia to Overall Motor Control

711

ganglia and then back to the cortex make virtually

all these loops

inhibitory neurotransmitter in most parts of the brain,

Clinical Syndromes Resulting from

Damage to the Basal Ganglia

Aside from athetosis and hemiballismus

already been mentioned in relation to lesions in the

paralysis agitans,

results from widespread destruction of that portion of

the substantia nigra (the pars compacta) that sends

dopamine-secreting nerve fibers to the caudate nucleus

untary tremor of the involved areas even when the

called akinesia.

caudate nucleus and putamen is an inhibitory transmit-

in the substantia nigra of the parkinsonian patient the-

oretically would allow the caudate nucleus and putamen

to become overly active and possibly cause continuous

output of excitatory signals to the corticospinal motor

Some of the feedback circuits might easily oscillate

because of high feedback gains after loss of their inhi-

tremor

tremor is quite different from that of cerebellar disease

because it occurs during all waking hours and therefore

is an involuntary tremor

forms intentionally initiated movements and therefore

is called

akinesia

much more distressing to the patient than are the symp-

person must exert the highest degree of concentration.

to make the desired movements is often at the limit of

nucleus accumbens

has been suggested that this might reduce the psychic

Administration of the drug

L

-

dopa

L

dopamine then restores the normal balance between

inhibition and excitation in the caudate nucleus and

have the same effect because dopamine has a chemical

structure that will not allow it to pass through the blood-

ture of

L

Another treatment for

L

destruction of most of the dopamine after it has been

helps to slow destruction of the dopamine-secreting

combinations of

L

-dopa therapy along with

L

-deprenyl

therapy usually provide much better treatment than use

obtained from the brains of aborted fetuses) into the

caudate nuclei and putamen has been used with some

Because abnormal signals from

the basal ganglia to the motor cortex cause most of the

have been made to treat these patients by blocking

lesions were made in the ventrolateral and ventroante-

feedback circuit from the basal ganglia to the cortex;

variable degrees of success were achieved—as well as

It is characterized at first by flicking movements in indi-

vidual muscles and then progressive severe distortional

are believed to be caused by loss of most of the cell

nucleus and putamen and of acetylcholine-secreting

tion is believed to allow spontaneous outbursts of

globus pallidus and substantia nigra activity that cause

cially in the thinking areas of the cerebral cortex.

situation, such as planning one’s immediate motor

cerebral and basal ganglia circuit, beginning in the

thus controlling dimensions of the patterns.