Fifth stage

MedicineLec-3

د.بشار

13/11/2016

CNS INFECTIONSdepend on the location of the infection (the meninges or the parenchyma of the brain and spinal cord), the causative organism (virus, bacterium, fungus or parasite), and whether the infection is acute or chronic

Meningitis

Acute infection of the meninges presents with a characteristic combination of pyrexia, headache and meningism.

Meningism consists of headache, photophobia and stiffness of the neck, often accompanied by other signs of meningeal irritation, including Kernig’s sign (extension at the knee with the hip joint flexed causes spasm in the hamstring muscles) and Brudzinski’s sign (passive flexion of the neck causes flexion of the hips and knees

Bacterial meningitis

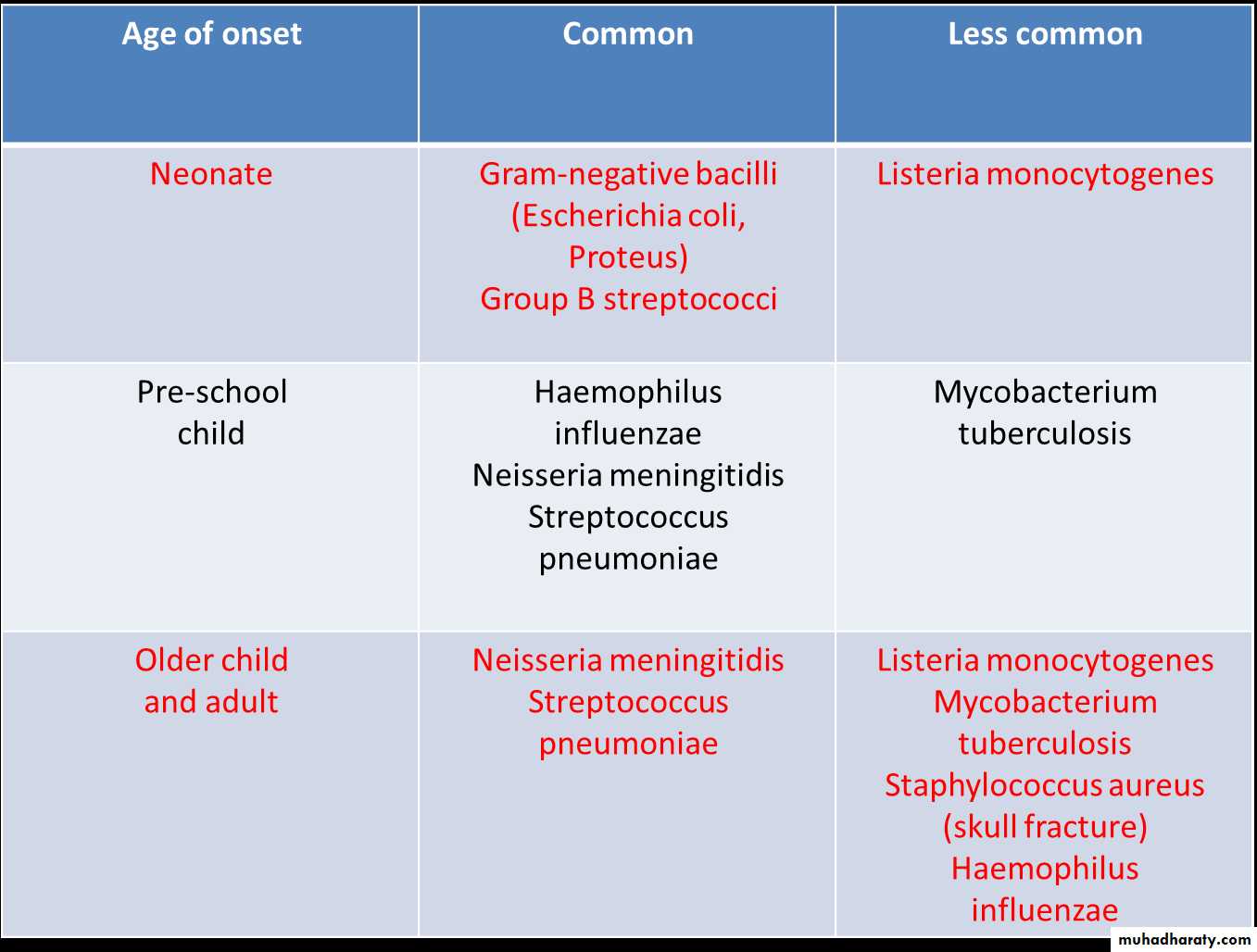

Many bacteria can cause meningitis but geographical patterns vary, as does age-related sensitivity

Bacterial causes of meningitis

Clinical features

Headache, drowsiness, fever and neck stiffness are the usual presenting features. In severe bacterial meningitis the patient may be comatose and later there may be focal neurological signs.

When accompanied by septicaemia, it may present very rapidly, with abrupt onset of obtundation due to cerebral oedema.

Complications of meningococcal septicaemia

MeningitisRash (morbilliform, petechial or purpuric)

Shock

Intravascular coagulation

Renal failure

Peripheral gangrene

Arthritis (septic or reactive)

Pericarditis (septic or reactive

In pneumococcal and Haemophilus infections there may be an associated otitis media.

Pneumococcal meningitis may be associated with pneumonia and occurs especially in older patients and alcoholics as well as those without functioning spleens

Listeria monocytogenes is an increasing cause of meningitis and brainstem encephalitis in the immunosuppressed, people with diabetes, alcoholics and pregnant women

Investigations

Lumbar puncture is mandatory unless there are contraindicationsIf the patient is drowsy and has focal neurological signs or seizures, is immunosuppressed, has undergone recent neurosurgery or has suffered a head injury, it is wise to obtain a CT to exclude a mass lesion (such as a cerebral abscess) before lumbar puncture because of the risk of coning.

This should not, however, delay treatment of a presumptive meningitis.

If lumbar puncture is deferred or omitted, it is essential to take blood cultures and to start empirical treatment

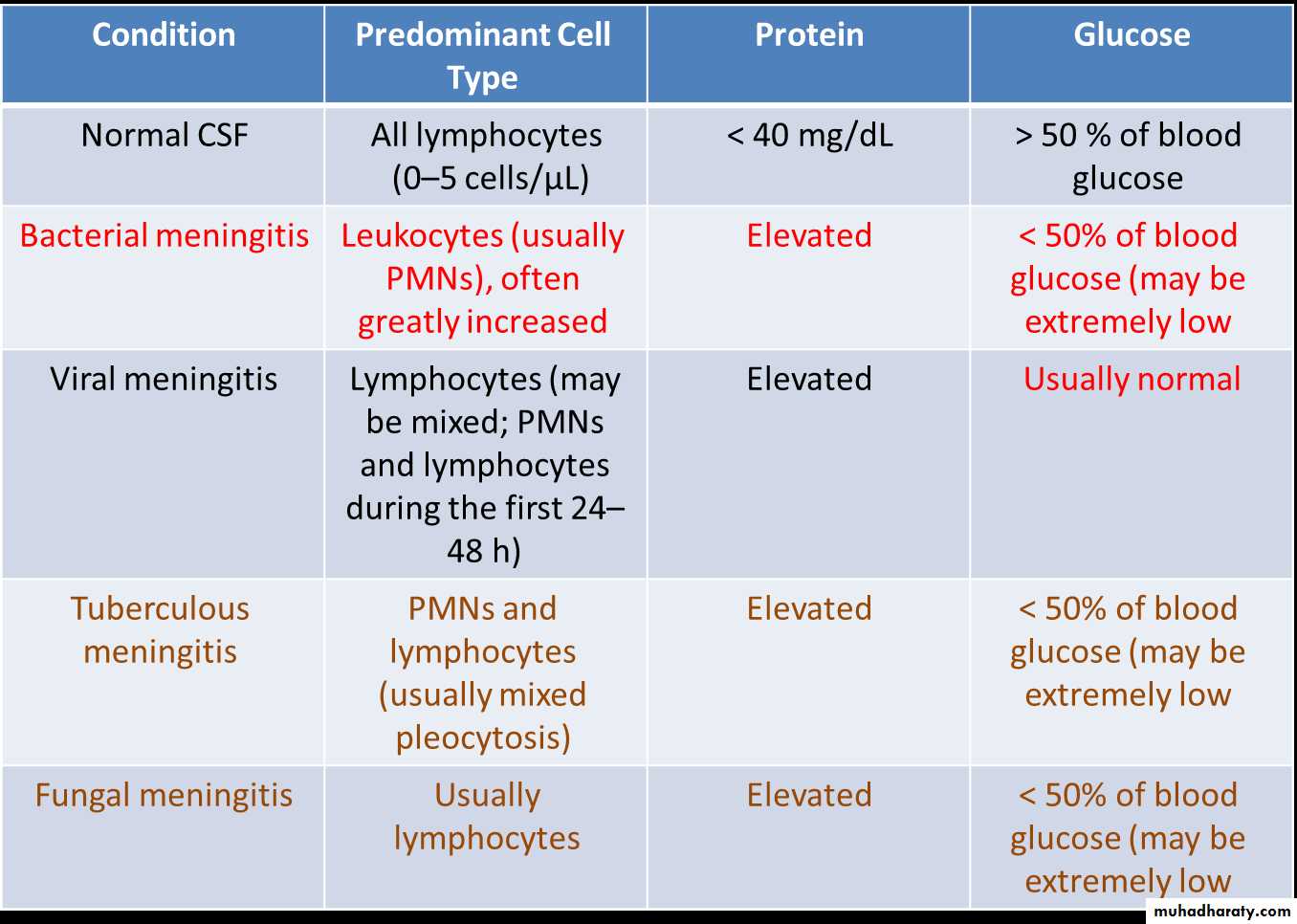

CSF Findings in Meningitis

Management

There is an untreated mortality rate of around 80%, so action must be swift.If bacterial meningitis is suspected, the patient should be given parenteral benzylpenicillin immediately (intravenous is preferable) and prompt hospital admission should be arranged. The only contraindication is a history of penicillin anaphylaxis.

Treatment of pyogenic meningitis of unknown cause

1. Adults aged 18–50 yrs with or without a typical meningococcal rash• Cefotaxime 2 g IV 4 times daily or

• Ceftriaxone 2 g IV twice daily

2. Patients in whom penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infection is suspected, or in areas with a significant incidence of penicillin resistance in the community

As for (1) but add:

• Vancomycin 1 g IV twice daily or

• Rifampicin 600 mg IV twice daily

3. Adults aged > 50 yrs and those in whom Listeria monocytogenes infection is suspected (brainstem signs, immunosuppression, diabetic, alcoholic)

As for (1) but add:

• Ampicillin 2 g IV 6 times daily or

• Co-trimoxazole 50 mg/kg IV daily in two divided doses

4. Patients with a clear history of anaphylaxis to β-lactams

• Chloramphenicol 25 mg/kg IV 4 times daily plus

• Vancomycin 1 g IV twice daily

5. Adjunctive treatment

• Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg 4 times daily for 2–4 days

• Corticosteroids significantly reduce hearing loss and neurological sequelae, but do not reduce overall mortality

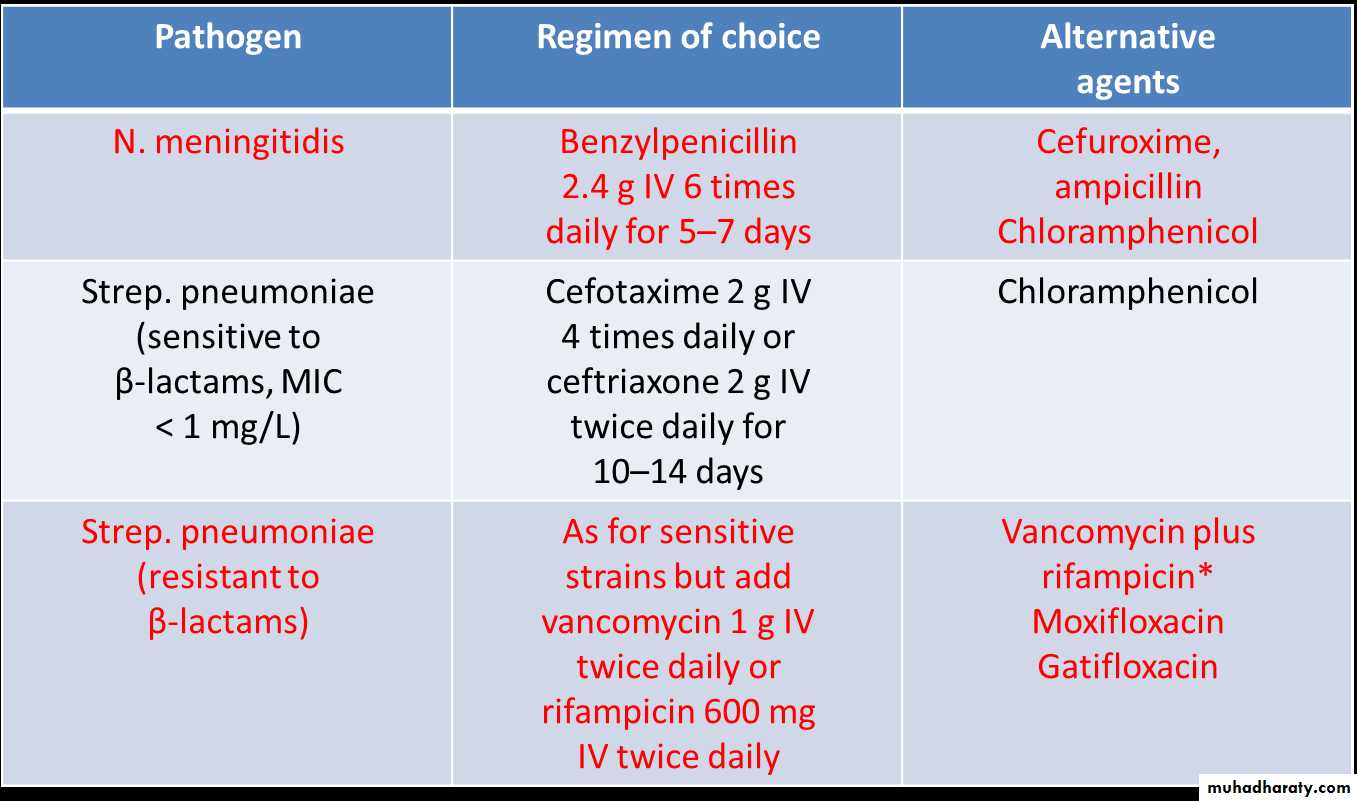

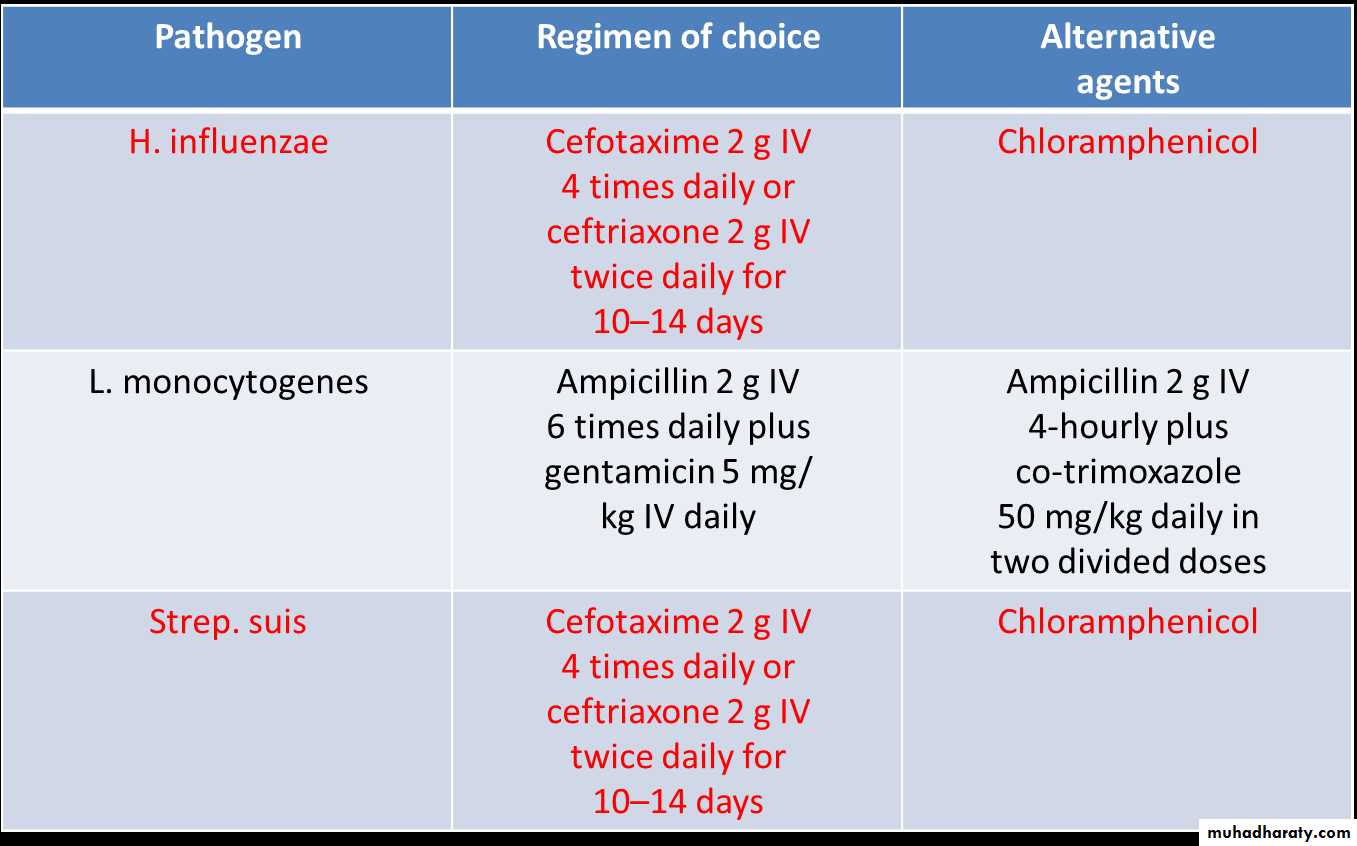

Chemotherapy of bacterial meningitis when the cause is known

Adverse prognostic features include

hypotensive shock,a rapidly developing rash,

a haemorrhagic diathesis,

multisystem failure

and age over 60 years.

Prevention of meningococcal infection

Close contacts of patients with meningococcal infection should be given 2 days of oral rifampicin.In adults, a single dose of ciprofloxacin is an alternative.

If not treated with ceftriaxone, the index case should be given similar treatment to clear infection from the nasopharynx before hospital discharge.

Vaccines are available for most meningococcal subgroups but not group B, which is among the most common serogroup isolated in many countries.

Tuberculous meningitis

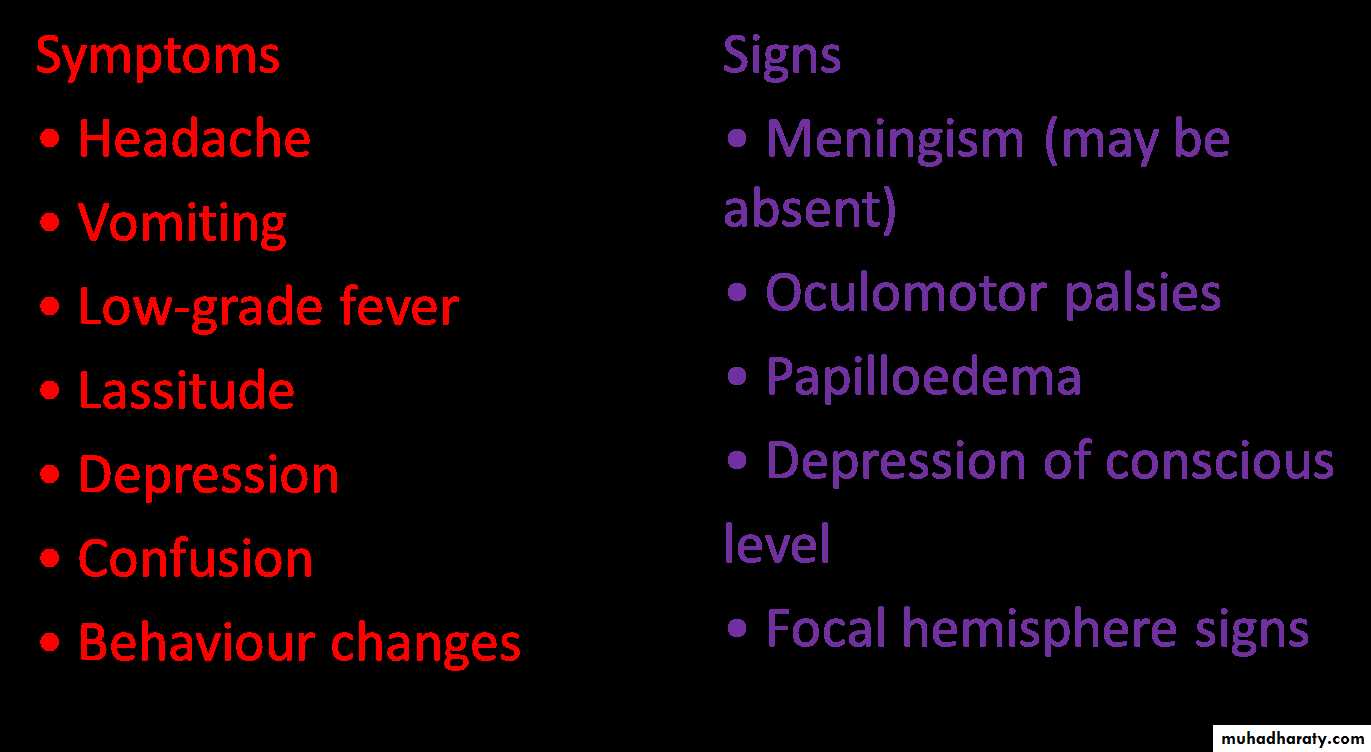

Tuberculous meningitis most commonly occurs shortly after a primary infection in childhood or as part of miliary tuberculosisClinical features of tuberculous meningitis

Onset is much slower than in other bacterial meningitis over 2–8 weeks.

If untreated, it is fatal in a few weeks but complete recovery is usual if treatment is started early.When treatment is initiated later, the rate of death or serious neurological deficit may be as high as 30%.

The tubercle bacillus may be detected in a smear of the centrifuged deposit from the CSF but a negative result does not exclude the diagnosis.

The CSF should be cultured but, as this result will not be known for up to 6 weeks, treatment must be started without waiting for confirmation.

Brain imaging may show hydrocephalus, brisk meningeal enhancement on enhanced CT or MRI, and/or an intracranial tuberculoma.

Management

As soon as the diagnosis is made or strongly suspected, chemotherapy should be started using one of the regimens that include pyrazinamide.The use of corticosteroids in addition to anti-tuberculous therapy has been controversial. Recent evidence suggests that it improves mortality, especially if given early, but not focal neurological damage.

Surgical ventricular drainage may be needed if obstructive hydrocephalus develops.

Viral meningitis

Viruses are the most common cause of meningitis, usually resulting in a benign and self-limiting illness requiring no specific therapy.A number of viruses can cause meningitis, the most common being enteroviruses.

Clinical features

Viral meningitis occurs mainly in children or young adults, with acute onset of headache and irritability and the rapid development of meningism. The headache is usually the most severe feature. There may be a high pyrexia but focal neurological signs are rare.

The diagnosis is made by lumbar puncture.

Management

There is no specific treatment and the condition is usually benign and self-limiting.

The patient should be treated symptomatically in a quiet environment. Recovery usually occurs within days

Viral encephalitis

Clinical features

Viral encephalitis presents with acute onset of headache, fever, focal neurological signs (aphasia and/or hemiplegia, visual field defects) and seizures. Disturbance of consciousness ranging from drowsiness to deep coma supervenes early and may advance dramatically.

Meningism occurs in many patients.

Investigations

Imaging by CT scan may show low-density lesions in the temporal lobes but MRI is more sensitive in detecting early abnormalities.Lumbar puncture should be performed once imaging has excluded a mass lesion. The CSF usually contains excess lymphocytes but polymorphonuclear cells may predominate in the early stages. The CSF may be normal in up to 10% of cases.

Some viruses, including the West Nile virus, may cause a sustained neutrophilic CSF. The protein content may be elevated but the glucose is normal.

The EEG is usually abnormal in the early stages, especially in herpes simplex encephalitis, with characteristic periodic slow-wave activity in the temporal lobes.

Virological investigations of the CSF, including PCR for viral DNA, may reveal the causative organism but treatment initiation should not await this.

Management

Optimum treatment for herpes simplex encephalitis (aciclovir 10 mg/kg IV 3 times daily for 2–3 weeks) hasreduced mortality from 70% to around 10%. This should be given early to all patients suspected of suffering from viral encephalitis.Some survivors will have residual epilepsy or cognitive impairment.

Anticonvulsant treatment may be needed and raised intracranial pressure may indicate the need for dexamethasone.

Cerebral abscess

Bacteria may enter the cerebral substance through penetrating injury, by direct spread from paranasal sinuses or the middle ear, or secondary to septicaemia. The site of abscess formation and the likely causative organism are both related to the source of infection.Initial infection leads to local suppuration followed by loculation of pus within a surrounding wall of gliosis, which in a chronic abscess may form a tough capsule.

Haematogenous spread may lead to multiple abscesses.

Clinical features

A cerebral abscess may present acutely with fever, headache, meningism and drowsiness, but more commonly presents over days or weeks as a cerebral mass lesion with little or no evidence of infection.

Seizures, raised intracranial pressure and focal hemisphere signs occur alone or in combination. Distinction from a cerebral tumour may be impossible on clinical grounds.

Investigations

Lumbar puncture is potentially hazardous in the presence of raised intracranial pressure and CT should always precede it.

CT reveals single or multiple lowdensity areas, which show ring enhancement with contrast and surrounding cerebral oedema.

There may be an elevated white blood cell count and ESR in patients with active local infection.

Management and prognosis

Antimicrobial therapy is indicated once the diagnosis is made. The likely source of infection should guide the choice of antibiotic.Surgical drainage by burr-hole aspiration or excision may be necessary, especially where the presence of a capsule may lead to a persistent focus of infection.

Epilepsy frequently develops and is often resistant to treatment.

Despite advances in therapy, the mortality rate remains at 10–20% and this may partly relate to delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

Include a number of veterinary and medical conditions that are characterised by the histopathological triad of cortical spongiform change, neuronal cell loss and gliosis. Associated with these changes, there is deposition of amyloid made up of an altered form of a normally occurring protein, the prion protein.Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker disease, fatal familial insomnia and kuru