I

Fifth stage

ENT

Lec-2

د.سنمار

15/11/2016

Epistaxis (nosebleed)

Although epistaxis (haemorrhage from the nose) is usually harmless, it may be life-

threatening disease. It affects all ages without sex predilection. Anterior epistaxis is more

common in child or young adult, while posterior nasal bleeding is more often seen in the

older adult with hypertension or arteriosclerosis. The incidence is higher during the winter

months when upper respiratory tract infections are more frequent.

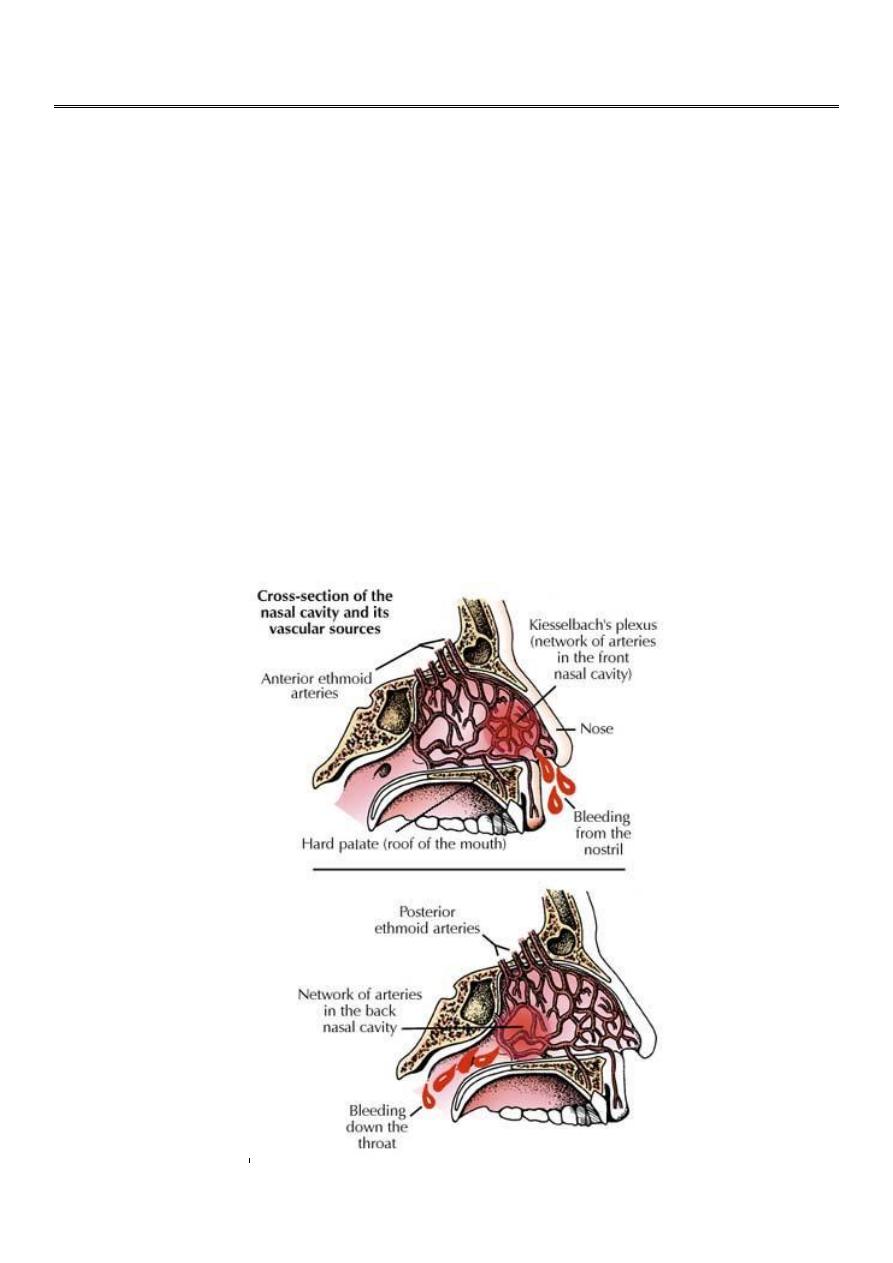

Sources of bleeding;

Bleeding from Kiesselbach`s plexus (Little area) forms about 90 % of cases. The mucosa in

this area is very fragile and is tightly adherent to the underlying cartilage and thus offers

little resistance to mechanical stress.

.

Sources of bleeding

II

Causes of epistaxis;

A. Local causes;

1) Idiopathic.

2) Trauma: Direct injury as nose picking, or nasal operations.

The two most common causes of recurrent epistaxis are idiopathy and trauma.

3) Inflammatory reactions

Local inflammatory reaction as a result of acute respiratory tract infection , allergic

disorders or sinusitis allow overgrowth of virulent bacteria and lead to dryness, crusting

,exposure and haemorrhage.

4) Anatomical and structural abnormalities

Septal deviation leads to abnormalities in airflow, causing certain areas of the mucosa to

be exposed to constant turbulent air currents, and causing the vessels to rupture with the

slightest traumatic insult such as rubbing.

5) Intranasal tumours, benign or malignant

These are rare causes of epistaxis but should not be forgotten (Unilateral obstruction with

haemorrhage in elderly patient may rise the suspicion of malignancy).

B. Systemic causes

1) Cardiovascular

Arteriosclerosis associated with hypertension is a common problem, particularly in the

elderly .The nasal mucosa is often atrophic and cracks easily. This eventually leads to

exposure of an elderly arteriosclerotic vessel, which can easily rupture during a hypertensive

episode, producing severe haemorrhage. Hypertension does not cause the epistaxis but

ensures continued haemorrhage once it starts.

III

2) Drugs: e.g.; warfarin, heparin, NSAIDs, methotrexate, alcohol, dipyridamole…etc.

3) Blood disorders

Leukemia, multiple myeloma, haemophilia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

(ITP) can lead to severe and persistent nosebleed.

4) Toxic agents: e.g. Heavy metals such as chromium, mercury and phosphorus.

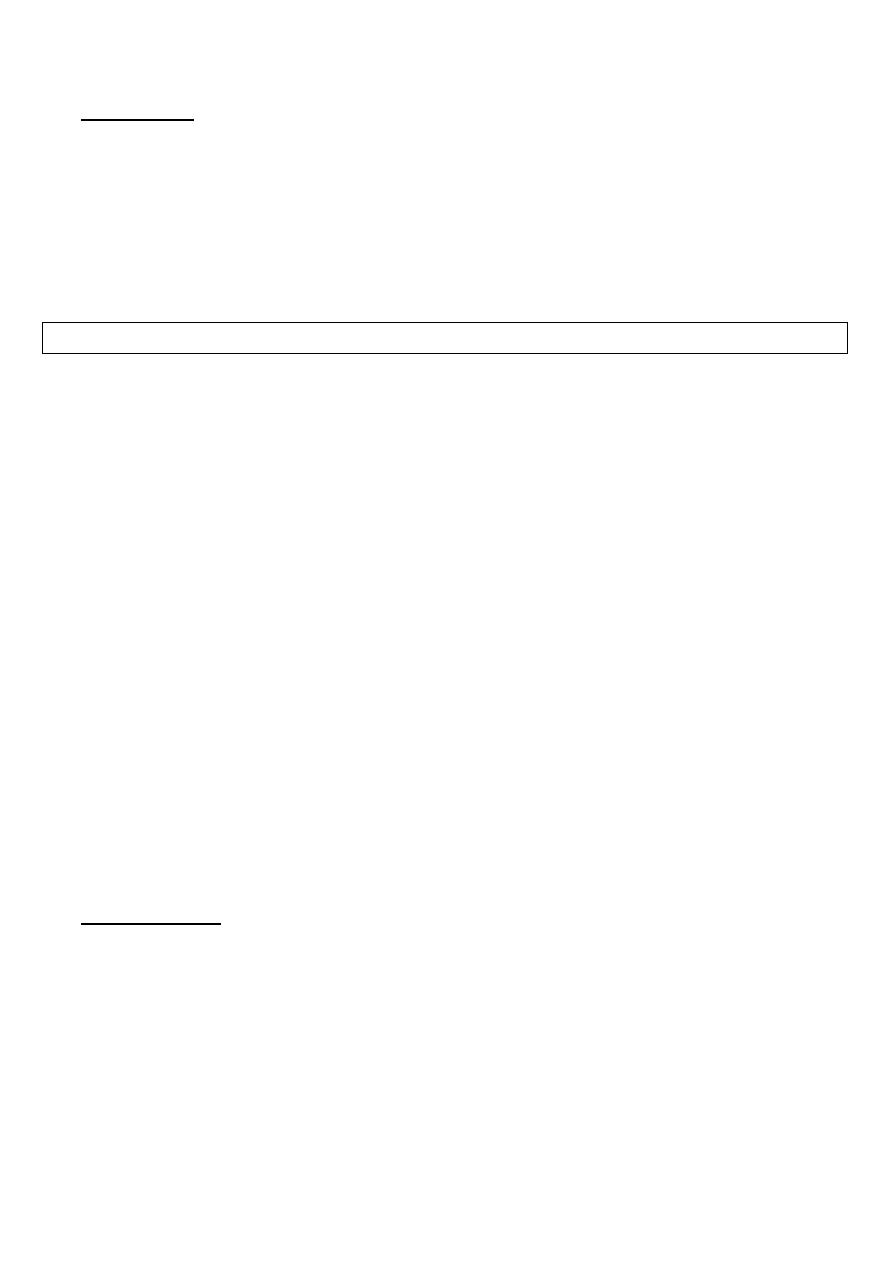

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease

5) Hereditary haemorrhagic

telangiectasia

This disease is also known as Osler-Weber-

Rendu disease and characterized by

abnormal capillaries, is a potent but

uncommon cause of recurrent epistaxis.

The disease can also cause haematuria,

melaena and cerebral haemorrhage.

Management;

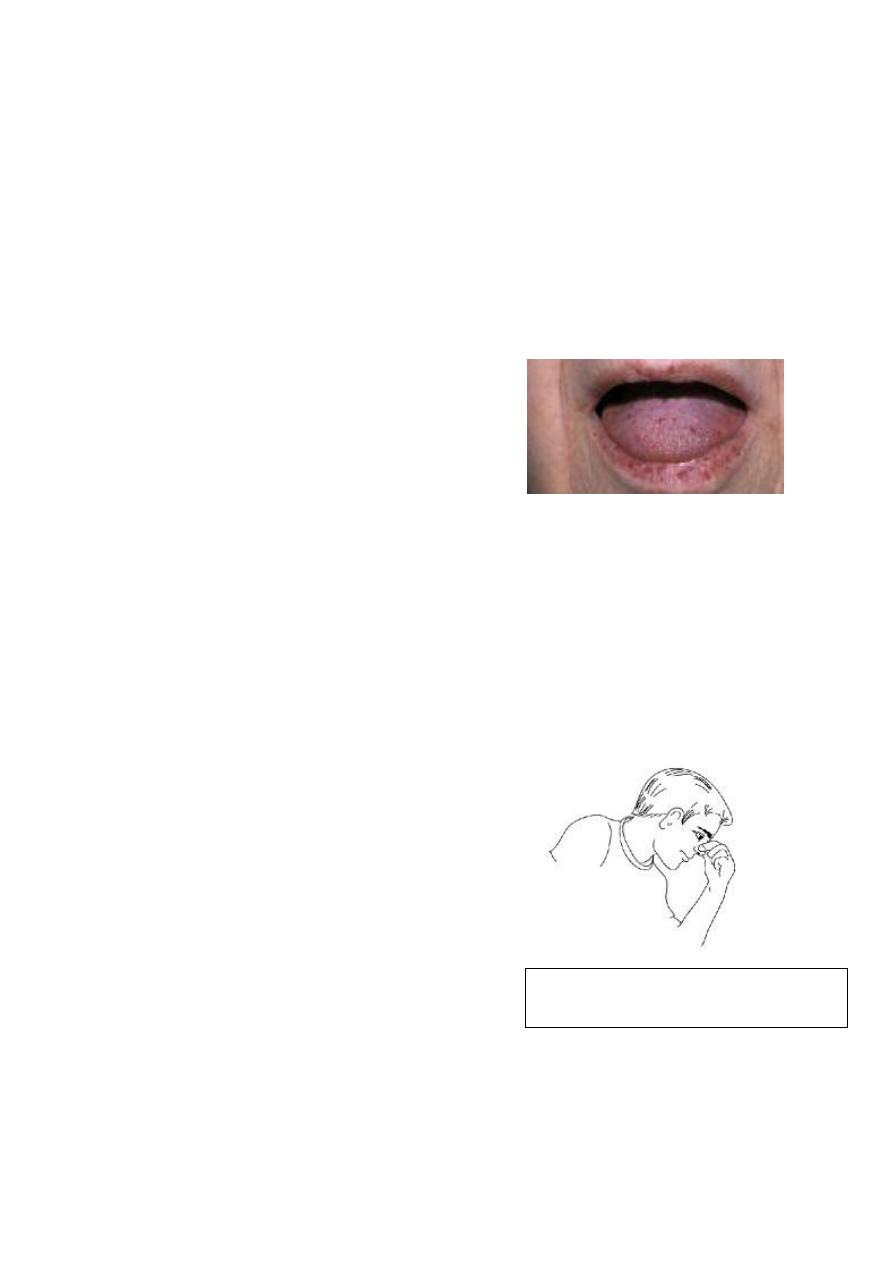

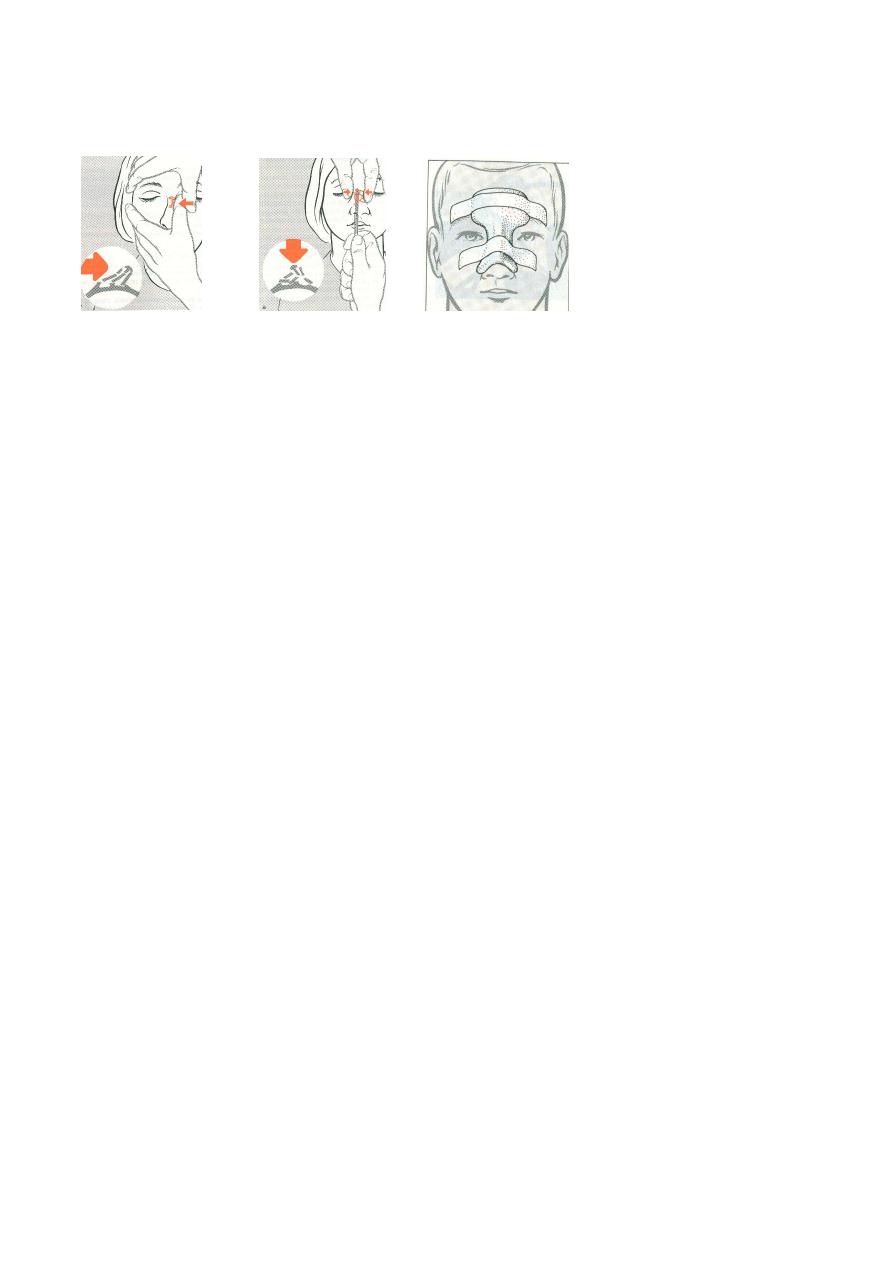

A. First aid management;

1. Arrest of haemorrhage;

Sit upright, lean forward and pinch

the nostrils.

Calming the patient (if necessary

with medication).

The nostrils should be pinched

together (compressing the bony

bridge is useless).

The patient should sit upright to

lower to blood pressure and lean

forward slightly over a container

so as not to swallow blood.

2. Assessment of blood loss;

Recording the pulse and blood pressure.

Look for signs of shock; pallor, raising pulse and sweating.

In severe blood loss;

IV

IV line should be inserted.

Blood taken for cross match.

Administration of suitable plasma expander.

3. Determination of cause;

A. History; trauma (surgical or non surgical), bleeding tendency (Haemophilia,

hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, ITP ...etc), liver disease, renal disease

and use of anticoagulant.

B. Hb, full blood count and clotting screen should be requested in all cases of

severe nosebleed.

4. Determination of site;

This requires removal of clots by suction or by asking the patient to blow his nose

gently. A cotton-wool pledglet soaked in vasoconstrictor (e.g. 1:1000 adrenaline) is very

useful technique. A search is then made in the clean dry nose for the responsible vessel.

B. Control of bleeding;

o Most nosebleeds stop spontaneously or after the simple measures mentioned above.

o If an active bleeding site is identified then cauterization (electrical or chemical-by silver

nitrate or trichloracetic acid) under local anaesthesia is required. Sometimes posterior

bleed is visualized by rigid endoscope and also controlled by cautery.

o

Cauterization

o If these measures fail, when the blood vessel cannot be seen or cauterized, then

physical pressure on the blood vessel is necessary to occlude it. This is achieved by

V

packing and clotting mechanism will occlude the blood vessel while the pack in place.

The pack requires to remain in situ for at least 48 hours to allow reasonable clotting.

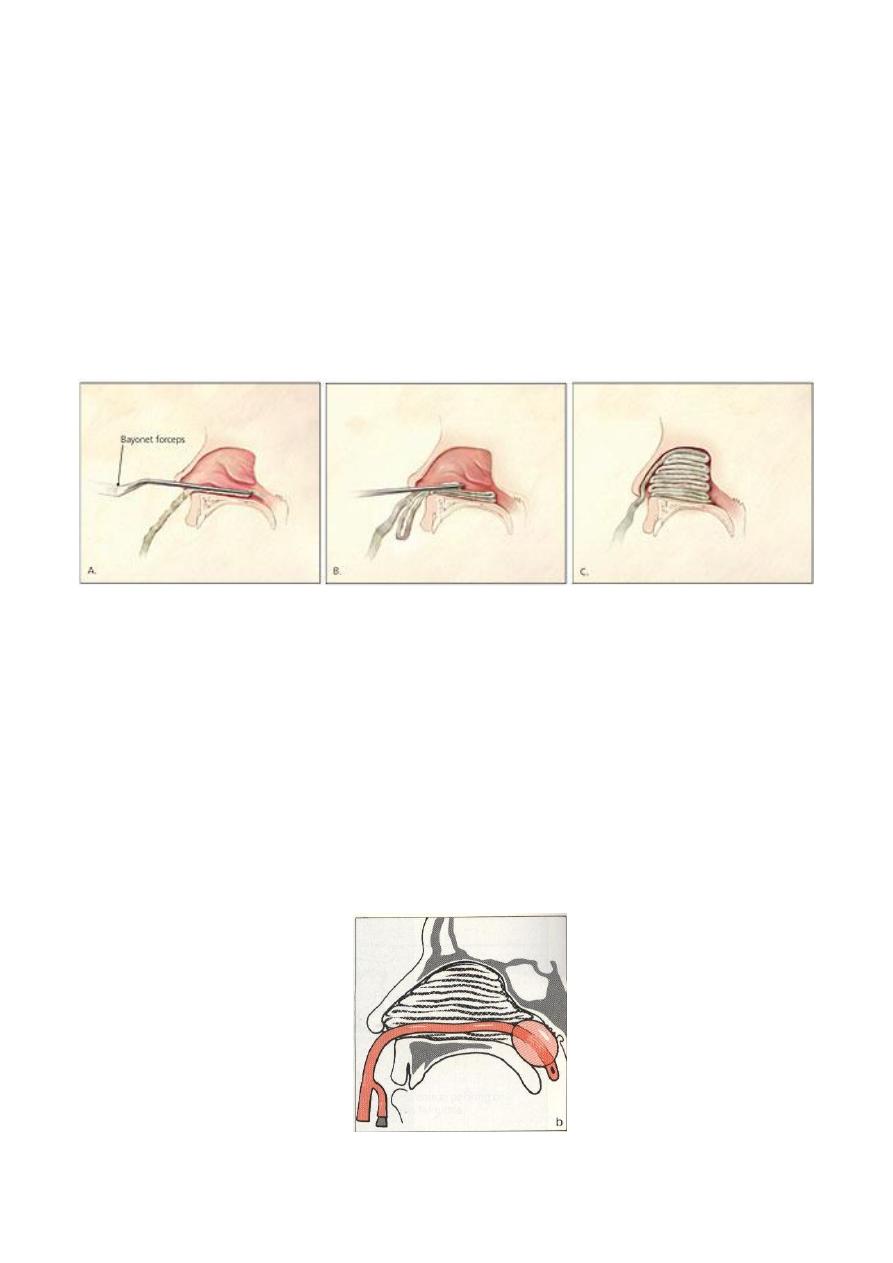

In anterior packing the best pack used is made up of a 0.5 in (1.25cm) is soaked in a

mixture of bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP). This substance is antiseptic and can

be left in the nose for a considerable time. It is important that the packing should be

built up in layers, starting on the flour of the nose and going as far back as possible,

then gradually building up toward the roof. Vaseline gauze and commercially produced

sponge` tampons` are alternatively used. Prophylactic antibiotics are important to

manage sinusitis from blockage of sinus ostea and to prevent toxic shock syndrome

secondary to toxin producing staphylococcus aureus.

Method of anterior packing

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

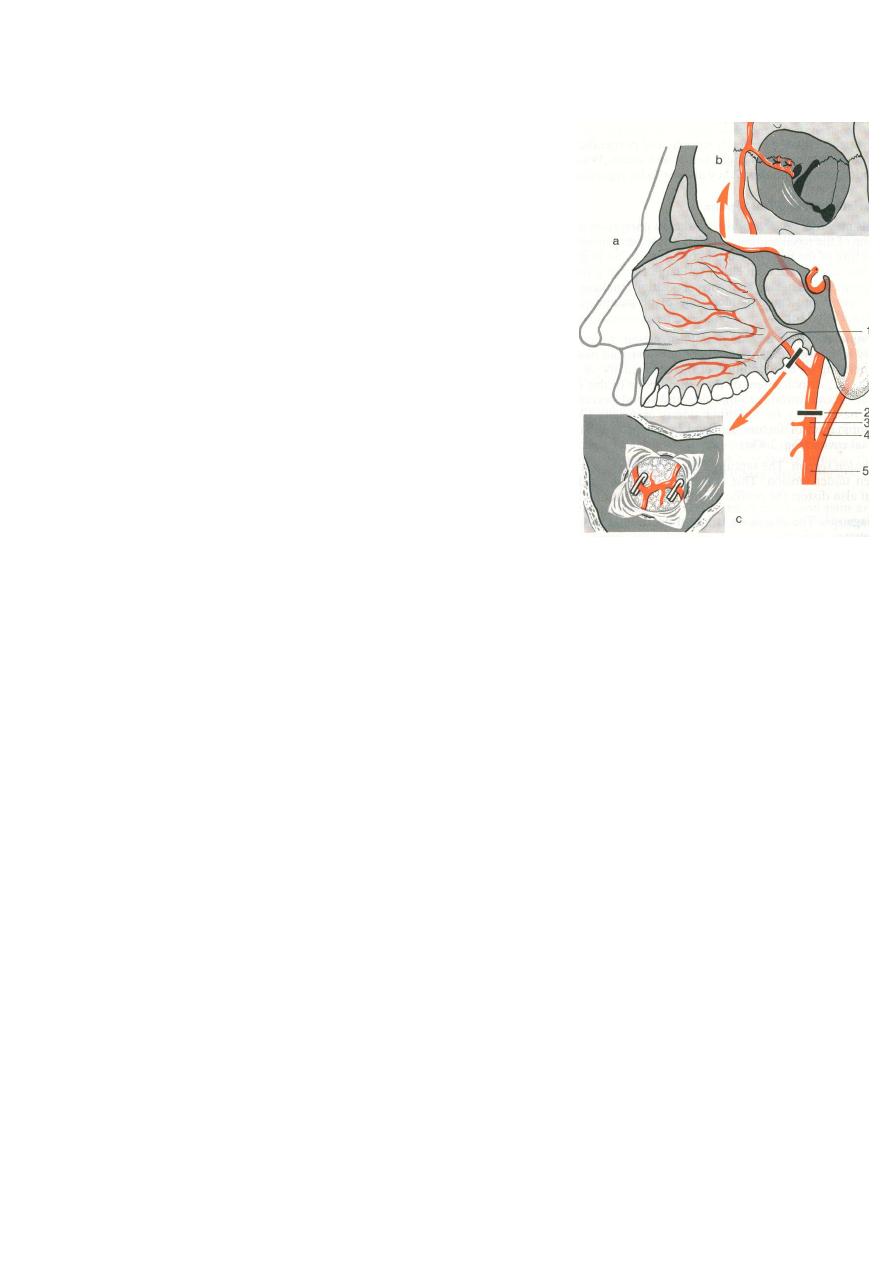

Continued haemorrhage despite anterior pack is probably a result of bleeding from the

posterior branches of sphenopalatine artery and will necessitate the insertion of a postnasal

pack. A simple post nasal pack is a Foley catheter which is inflated once correctly positioned.

This can be performed without general anaesthesia. The post nasal pack must be associated

with anterior pack.

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

Postnasal pack by Foley's catheter

o

o

o

o

o

o

VI

If bleeding continues despite anterior and posterior packing, then we have to go through

the following steps;

1. Examination under general anaesthesia. Any

septal deviation which might hide bleeding

points or prevent adequate packing is dealt

with. Nasal endoscopy may help to locate the

offending blood vessel. If, despite a thorough

search, no obvious bleeding site can be found,

a more thorough packing of anterior and

posterior nasal fossae should then be

performed.

2. If, despite anterior and posterior packing under

general anaesthesia the bleeding continue or

recurs, surgical ligation of the arterial supply of

the nose may be necessary. Three main surgical

procedures are described ;

1) Anterior ethmoidal artery ligation.

2) Maxillary artery ligation.

3) External carotid artery ligation.

Arterial ligation

Nasal Fractures

Usually caused by a blunt trauma to the nose and occasionally by penetrating wounds.

This

can occur in isolation or in combination with fractures of the maxilla or zygomatic arch.

We should not forget that the patient may also have received a head injury.

Clinical Picture

1. Deformity, black eye and swelling.

2. Pain and headache.

3. Epistaxis.

4. Nasal obstruction due to septal haematoma or septal dislocation.

5. Crepitus and nasal mobility.

Remember to inquire regarding preexisting deformity.

Investigations

X.ray is important medicolegally but of little value clinically.

Treatment

Early (hours): Before swelling appear----- immediate reduction (Open fracture or

septal haematoma requires immediate treatment.).

VII

Intermediate (Days): When oedema obscures the deformity -----Wait 5-6 days till the

swelling subside.

Late ( months or years): Septorhinoplasty for persistent deformity

Reduction of fracture and dorsal splint

A protective dorsal splint is placed for about 7 days. Intranasal packing is used to

prevent depression of unstable bone fragments. Treatment becomes more difficult

after 10-14 days in adult and 7-10 days in children, as the bones begin to set.

Foreign bodies in the Nose

They are much more common in children. The F.B. may be organic or inorganic. An

inflammatory reaction follows accompanied by nasal discharge.

Clinical Picture

1. Unilateral foul smelling nasal discharge. In a child, unilateral purulent discharge is

pathognomonic of foreign body.

2. Epistaxis.

3. Pain.

.

Investigations

X – ray if the foreign body is radiopaque.

Treatment

Removal of the FB by a probe, hook or forceps, sometimes G.A. is required.

Rhinolith

Hard masses in the nasal cavity consist of deposits of phosphate, and carbonate of

calcium and magnesium around a central nucleus called the nidus.

Aetiology

The nidus may be

1. F.B.

VIII

2. Dried blood and pus.

Clinical Picture

1. Unilateral offensive nasal discharge.

2. Unilateral nasal obstruction.

3. If it is long standing, it leads to atrophy of the nasal mucosa.

Examination; Probe --- hard mass can be felt.

Investigations; X - ray

Treatment; Removal under G.A.

Disorders of nasal septum

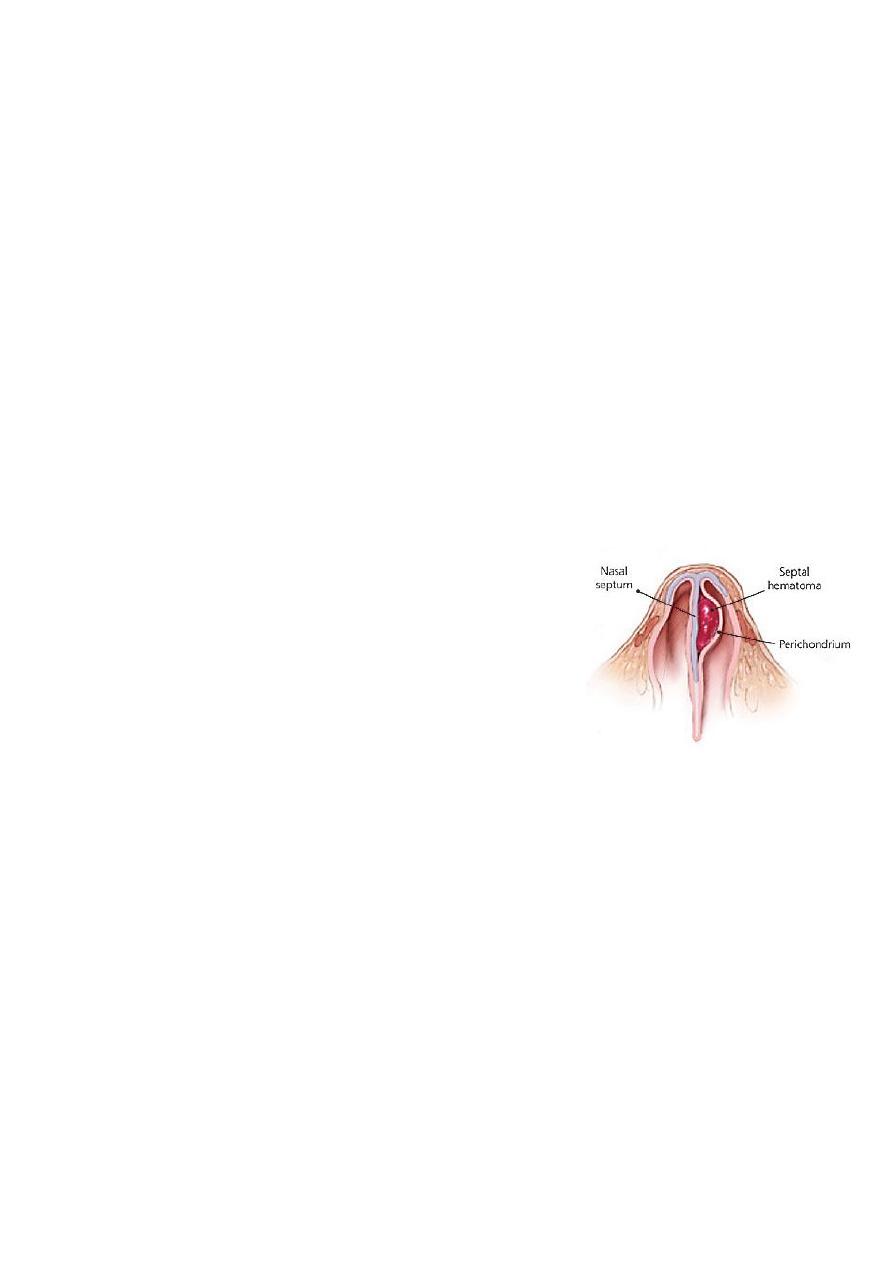

1. Septal haematoma:

Collection of blood beneath the mucoperichondrium or

mucoperiosteum of the nasal septum.

Therefore

haematoma. separate the cartilage from its blood supply

may cause cartilaginous atrophy and necrosis.

Aetiology

1.

Trauma to the nose. 2. Septal surgery. 3. Blood dyscrasia.

Clinical Picture

1. Nasal obstruction 2. Septal swelling.

Complications

1. Infection of the haematoma with septal abscess ,cartilage necrosis and perforation.

2. External deformity (Saddle-nose)

IX

Treatment; The haematoma must be incised and drained followed by application of a pack

in the nasal cavity with antibiotic cover.

2. Septal Abscess:

Is collection of pus beneath the mucoperichondrium or the mucoperiostium.

Aetiology

1. Complication of haematoma. Blood provide excellent bacterial medium and result in

septal abscess

2. May follow furunculosis, measles or scarlet fever.

Clinical Picture

Nasal obstruction, fever, pain and tenderness over the nasal bridge.

Examination

Symmetrical swelling of the nasal septum.

Complications

1. Cartilage necrosis leading to perforation and external deformity.

2. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis.

Treatment

1. Drainage+packing+antibiotics.

2. Plastic surgery for external nasal deformities.

3. Septal deviation:

Generally a few adults have a complete straight septum. Only gross deflections causing

symptoms require treatment.

Aetiology

1- Trauma: Either birth trauma or external injury.

X

2- Developmental errors: The developing septum buckles because it grows faster than its

surrounding skeletal framework.

Symptoms

1- Nasal obstruction which may be unilateral or bilateral.

2- Recurrent sinus infection due to interference with sinus ventilation and drainage.

3- Headache due to malventilation of the frontal sinus (vacuum headache).

4- Epistaxis result from a prominent vessel over a bony spur.

Examination

1. External nasal deformity.

2. The deviation may be S or C shaped.

3. Signs of sinus infection.

Treatment;

1- Mild no Rx.

2- Symptomatic:

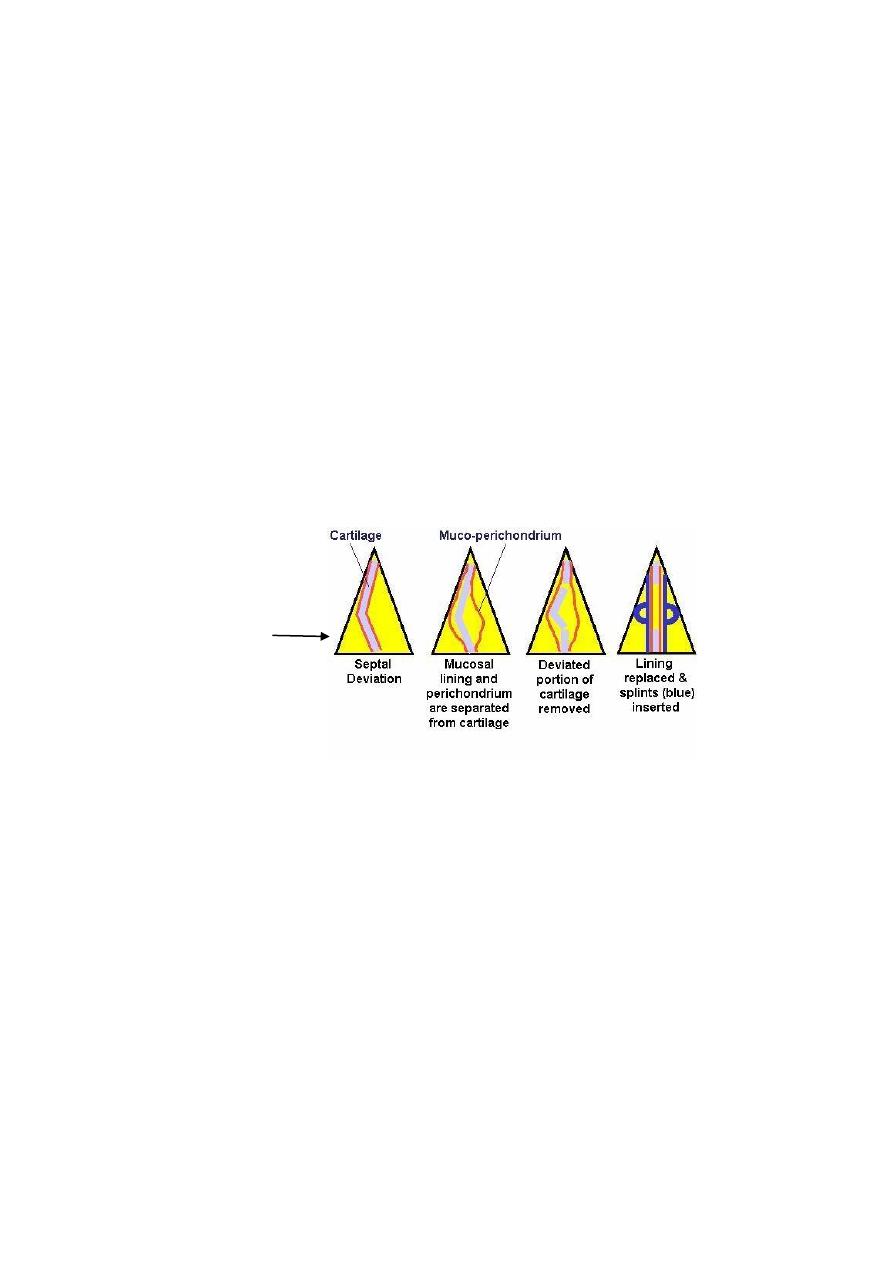

a) Submucous resection SMR

b) Septoplasty: i.e.;

4. Ulceration and perforation of the septum:

Aetiology;

1) Trauma; surgical, repeated cautery, digital trauma(nose picking)

2) Malignant disease.

3) Chronic inflammation; TB, syphilis

4) Poisons; industrial, cocaine addicts, topical corticosteroid, topical decongestants.

5) Idiopathic.

If small the perforation may produce an irritating whistling noise with respiration and if

larger it produces a considerable crusting with subsequent bleeding.

Treatment;

1. Treat the cause.

2. Medical: alkaline nasal douche + 25% glucose in glycerine.

3. Surgical closure but with poor success rate.

Repositioning of the

deviated cartilage with

minimal resection

XI

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Rhinorrhoea

Aetiology

1- Trauma: fracture of the base of the skull e.g. the cribriform plate and the posterior wall

of the frontal sinus

2- Spontaneous: Destructive lesion involving the floor of the anterior cranial fossa

Clinical Picture

1- Watery fluid drips from the nose which increase in bending forward.

2- Meningitis.

Examination

1- Handkerchief test: The fluid associated with rhinitis contains mucous which stiffens a

handkerchief while CSF does not.

2- Nasal endoscope to see the site of the lesion.

Investigations

1- Identification of glucose in the secretion.

2- Injection of radioactive material into CSF via

lumber puncture.

3- CT. scan of the base of the skull.

Treatment

1- Medical

a- Bed rest in head up position.

b- Systemic antibiotics.

c- Avoidance of nose blowing and avoidance of nasal packing.

d- Reduction of CSF production rate by drugs ( acetazolamide , frusemide ) or by

repeated lumber puncture.

2- Surgical: if no response to medical treatment after 10-14 days, then;

a- Treat the cause.

XII

b- Craniotomy and fascial graft of the leaking site.

Oroantral fistula

A fistula that communicates the oral cavity with the maxillary sinus.

Aetiology

1- Dental extraction , particularly of the 1

st

upper molar teeth.

2- Malignant tumours of the antrum.

3- Penetrating wound.

4- Fistula following Caldwell-Luc operation.

Clinical Picture

1- Foul sinusitis and discharge of pus into the mouth.

2- Regurgitation of food particles and air into the nose.

Examination

1- Leakage of air from the fistula when the patient blows with a closed nose and open

mouth.

2- A probe can be passed from the mouth to the antrum.

Treatment

1- Immediate following dental extraction

suturing.

2- Late

Remove any retained food particles, control infection and then closure using a

mucoperiosteal flap.

Choanal Atresia

Congenital atresia of the posterior nares due to persistence of the bucconasal

membrane, usually unilateral but bilateral cases can occur and observed at birth because the

neonate is obligate nasal breather.

XIII

The obstruction either composed of bone (most commonly) or membrane.

The condition occurs in 1 out of every 7,000 to 8,000 live births.

Clinical Picture

Females are commonly affected than males.

Bilateral

Neonatal emergency leads to asphyxia because the infant is obligate nasal

breather and commonly associated with other congenital anomalies.

Unilateral-(60%) with a right-sided predominance

nasal obstruction and excessive nasal

discharge in the affected side which may be not noticed for some years.

Examination

1. Total absence of nasal air flow by mirror test and cotton test.

2. Plastic catheter or probe can’t be passed through the affected side to the nasopharynx.

3. Fibroptic endoscopy.

Investigations

Contrast radiography by instillation of radioopaque substance in the affected side.

CT scan to see the thickness of a bony atresia.

Treatment

Unilateral elective perforation of the occlusion usually prior starting of school.

Bilateral

oral airway

surgical intervention.

XIV