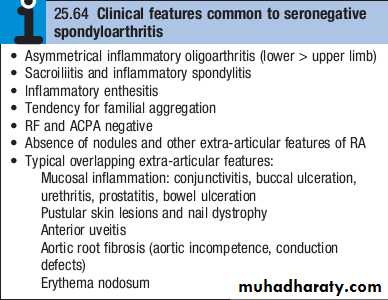

SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

DR. ALI A. YOUNISSERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

These comprise a group of related inflammatory jointdiseases, which show considerable overlap in their clinical features and a shared immunogenetic association with the HLAB27 antigen . They include:

• ankylosing spondylitis

• axial spondyloarthritis

• reactive arthritis, including Reiter’s syndrome

• psoriatic arthritis

• arthropathy associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

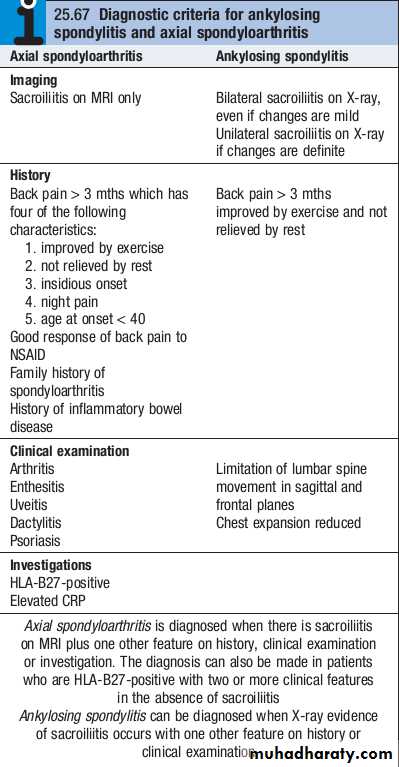

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is characterised by a chronic inflammatory arthritis predominantly affecting the sacroiliac joints and spine, which can progress to bony fusion of the spine.The onset is typically between the ages of 20 and 30, with a male preponderance of about 3 : 1.

In Europe, more than 90% of those affected are HLAB27 positive.

Even if severe ankylosis develops, functional limitation may not be marked as long as the spine is fused in an erect posture.

Pathophysiology

Ankylosing spondylitis is thought to arise from an as yet illdefined interaction between environmental pathogens and the host immune system in genetically susceptible individuals.

Increased faecal carriage of Klebsiella Aerogenes occurs in patients with established AS and may relate to exacerbation of both joint and eye disease.

Wider alterations in the human gut microbial environment are increasingly implicated, which could lead to increased levels of circulating cytokines such as IL23 that can activate enthesial or synovial T cells.

The HLAB27 molecule itself is implicated through its antigenpresenting function (it is a class I MHC molecule) or because of its propensity to form homodimers that activate leucocytes.

Clinical features

The cardinal feature is low back pain and early morning stiffness with radiation to the buttocks or posterior thighs.Symptoms are exacerbated by inactivity and relieved by movement.

The disease tends to ascend slowly, ultimately involving the whole spine, although some patients present with symptoms of the thoracic or cervical spine.

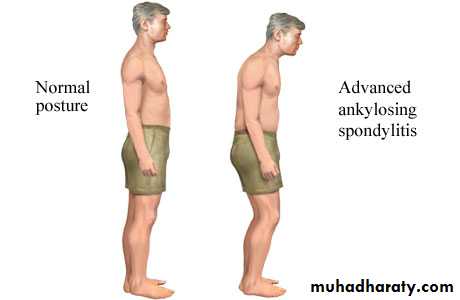

As the disease progresses, the spine becomes increasingly rigid as ankylosis occurs.

Secondary osteoporosis of the vertebral bodies frequently occurs, leading to an increased risk of vertebral fracture.

Clinical features

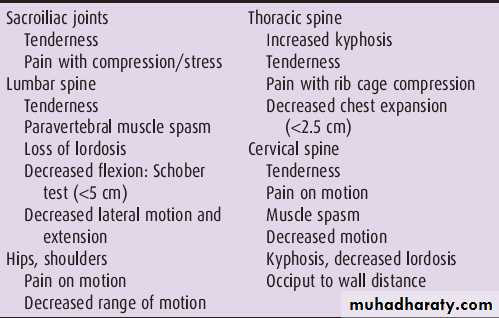

Early physical signs include a reduced range of lumbar spine movements in all directions and pain on sacroiliac stressing.As the disease progresses, stiffness increases throughout the spine and chest expansion becomes restricted.

Spinal fusion varies in its extent and in most cases does not cause a gross flexion deformity, but a few patients develop marked kyphosis of the dorsal and cervical spine that may interfere with forward vision.

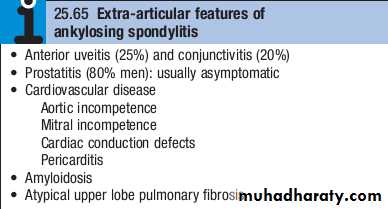

Pleuritic chest pain aggravated by breathing is common and results from costovertebral joint involvement.

Plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis and tenderness over bony prominences such as the iliac crest and greater trochanter may all occur, reflecting inflammation at the sites of tendon insertions (enthesitis).

Describe six physical examination tests used to assess sacroiliac joint tenderness or progression of spinal disease in AS.

Occiput-to-wall test. Assesses loss of cervical range of motion. Normally with the heels and scapulae touching the wall, the occiput should also touch the wall. Any distance from the occiput to the wall represents a forward stoop of the neck secondary to cervical spine involvement with AS. The tragus-to-wall test could also be used.

Chest expansion. Detects limited chest mobility. Measured at the fourth intercostal space in men and just below the breasts in women, normal chest expansion is approximately 5 cm. Chest expansion less than 2.5 cm is abnormal.

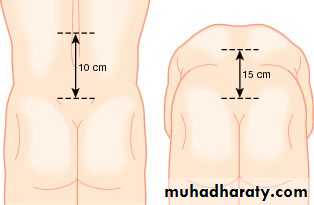

Schober test (modified).Detects limitation of forward flexion of the lumbar spine. Place a mark at the level of the posterior superior iliac spine (dimples of Venus) and another 10 cm above in the midline. With maximal forward spinal flexion with locked knees, the measured distance should increase from 10 cm to at least 15 cm .

Describe six physical examination tests used to assess sacroiliac joint tenderness or progression of spinal disease in AS

Other spinal mobility tests will show that lateral flexion and spinal rotation are also diminished, establishing that the patient has a global loss of spinal mobility.

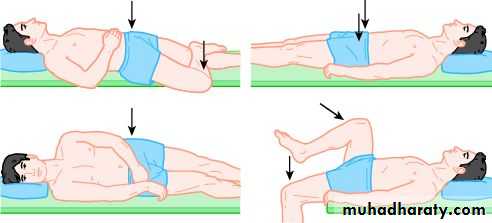

Pelvic compression. With the patient lying on one side, compression of the pelvis should elicit sacroiliac joint pain.

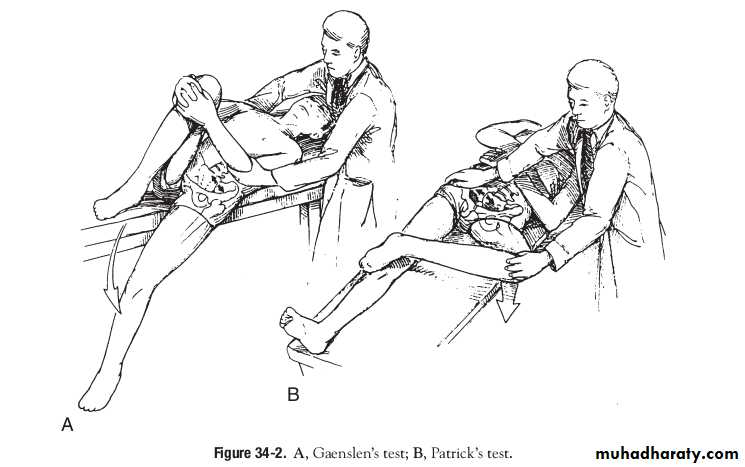

Gaenslen’s test. With the patient supine, a leg is allowed to drop over the side of the examination table while the patient draws the other leg toward the chest. This test should elicit sacroiliac joint pain on the side of the dropped leg .

Patrick’s test.With the patient’s heel placed on the opposite knee, downward pressure on the flexed knee with the hip now in flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) should elicit sacroiliac joint tenderness.

Clinical features

Up to 40% of patients also have peripheral arthritis. This is usually asymmetrical, affecting large joints such as the hips, knees, ankles and shoulders.In about 10% of cases, involvement of a peripheral joint may antedate spinal symptoms.

In a further 10%, symptoms begin in childhood, as in the syndrome of oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Fatigue is a major complaint and may result from both chronic interruption of sleep due to pain, and chronic systemic inflammation with direct effects of inflammatory cytokines on the brain.

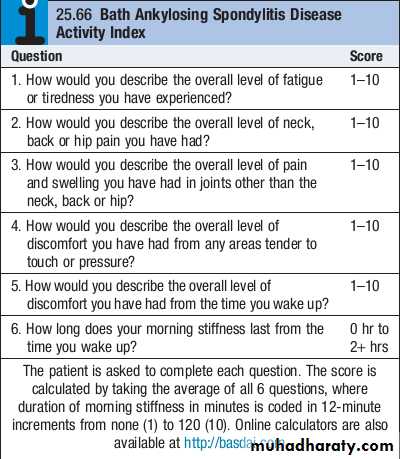

Assessment of disease activity

Disease activity in AS can be assessed by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), a questionnaire in which patients and their physician rate severity of various symptomsThis is important in assessing eligibility for biological treatment.

Investigations

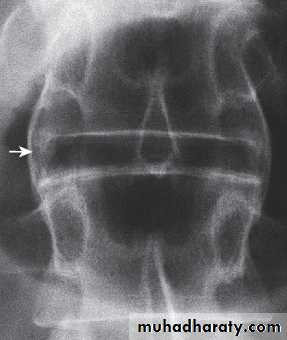

In established AS, radiographs of the sacroiliac joint show irregularity and loss of cortical margins, widening of the joint space and subsequently sclerosis, joint space narrowing and fusion.

Lateral thoracolumbar spine Xrays may show anterior ‘squaring’ of vertebrae due to erosion and sclerosis of the anterior corners and periostitis of the waist.

Bridging syndesmophytes may also be seen. These are areas of calcification that follow the outermost fibres of the annulus

Investigations

In advanced disease, ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament and facet joint fusion may also be visible. The combination of these features may result in the typical ‘bamboo’ spine.

Erosive changes may be seen in the symphysis pubis, the ischial tuberosities and peripheral joints.

Osteoporosis and atlantoaxial dislocation can occur as late features.

Patients with early disease can have normal Xrays, and if clinical suspicion is high, MRI should be performed. This is much more sensitive for detection of early sacroiliitis than Xray and can also detect inflammatory changes in the lumbar spine.

Investigations

The ESR and CRP are usually raised in active disease but may be normal.Testing for HLAB27 can be helpful, especially in patients with back pain suggestive of an inflammatory cause, when other investigations have yielded equivocal results.

Autoantibodies such as RF, ACPA and ANA are negative.

Management

The aims of management are to relieve pain and stiffness, maintain a maximal range of skeletal mobility and avoid the development of deformities.Education and appropriate physical activity are the cornerstones of management.

Early in the disease, patients should be taught to perform daily back extension exercises, including a morning ‘warmup’ routine, and to punctuate prolonged periods of inactivity with regular breaks. Swimming is ideal exercise. Poor posture must be avoided.

Management

NSAIDs and analgesics are often effective in relieving symptoms and may alter the underlying course of the disease. A longacting NSAID at night is helpful for alleviation of morning stiffness.Peripheral arthritis can be treated with methotrexate or sulfasalazine, but these drugs have no effect on axial disease.

AntiTNF therapy should be considered in patients who are inadequately controlled on standard therapy with a BASDAI score of ≥4.0 and a spinal pain score of ≥4.0.

AntiTNF therapy frequently improves symptoms but has not been shown to prevent ankylosis or alter natural history of the disease.

Other biological interventions using agents developed for RA have been disappointing, suggesting fundamental differences in disease pathogenesis.

Management

Local corticosteroid injections can be useful for persistent plantar fasciitis, other enthesopathies and peripheral arthritis.

Oral corticosteroids may be required for acute uveitis but do not help spinal disease.

Severe hip, knee or shoulder restriction may require surgery. Total hip arthroplasty has largely removed the need for difficult spinal surgery in those with advanced deformity.

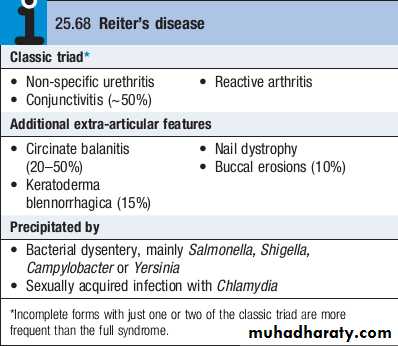

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis (previously known as Reiter’s disease) is predominantly a disease of young men, with a male preponderance of 15 : 1.It is the most common cause of inflammatory arthritis in men aged 16–35 but may occur at any age.

Reactive arthritis may present with triad of non-specific urethritis, reactive arthritis,and conjunctivitis, but many patients present with arthritis only.

Clinical features

The onset is typically acute, with an inflammatory oligoarthritis that is asymmetrical and targets lower limb joints, such as the knees, ankles, midtarsal and MTP joints.It occasionally presents with single joint involvement and no clear history of an infectious trigger.

There may be considerable systemic disturbance, with fever and weight loss.

Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis may also be present.

The first attack of arthritis is usually selflimiting, but recurrent or chronic arthritis develops in more than 60% of patients, and about 10% still have active disease 20 years after the initial presentation.

Low back pain and stiffness are common and 15–20% of patients develop sacroiliitis.

Investigations

The diagnosis is usually made clinically but joint aspiration may be required to exclude crystal arthritis and articular infection.Synovial fluid is leucocyterich and may contain multinucleated macrophages (Reiter’s cells).

ESR and CRP are raised during an acute attack.

Urethritis may be confirmed in the ‘twoglass test’ by demonstration of mucoid threads in the firstvoid specimen that clear in the second.

High vaginal swabs may reveal Chlamydia on culture.

Except for postSalmonella arthritis, stool cultures are usually negative by the time the arthritis presents, but serum agglutinin tests may help confirm previous dysentery.

RF, ACPA and ANA are negative.

Investigations

In chronic or recurrent disease, Xrays show periarticular osteoporosis, joint space narrowing and proliferative erosions.

Another characteristic feature is periostitis, especially of metatarsals, phalanges and pelvis, and large, ‘fluffy’ calcaneal spurs.

In contrast to AS, radiographic sacroiliitis is often asymmetrical and sometimes unilateral, and syndesmophytes are predominantly coarse and asymmetrical, often extending beyond the contours of the annulus (‘nonmarginal’)

Xray changes in the peripheral joints and spine are identical to those in psoriasis.

Management

The acute attack should be treated with rest, oral NSAIDs and analgesics.Intraarticular steroids may be required in patients with severe synovitis.

Nonspecific chlamydial urethritis is usually treated with a short course of doxycycline or a single dose of azithromycin, and this may reduce the frequency of arthritis in sexually acquired cases.

Treatment with DMARDs should be considered for patients with persistent marked symptoms, recurrent arthritis or severe keratoderma blennorrhagica.

Anterior uveitis is a medical emergency requiring topical, subconjunctival or systemic corticosteroids.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) occurs in 7–20% of patients with psoriasis and in up to 0.6% of the general population.The onset is usually between 25 and 40 years of age.

Most patients (70%) have preexisting psoriasis but in 20% the arthritis predates the occurrence of skin disease. Occasionally, the arthritis and psoriasis develop synchronously.

Clinical features

The presentation is with pain and swelling affecting the joints and entheses.

Several patterns of joint involvement are recognised but the course is generally one of intermittent exacerbation followed by varying periods of complete or nearcomplete remission.

Destructive arthritis and disability are uncommon, except in the case of arthritis mutilans.

PATTERNS OF PsA

Asymmetrical inflammatory oligoarthritis affects about 40% of patients and often presents abruptly with a combination of synovitis and adjacent periarticular inflammation.This occurs most characteristically in the hands and feet, when synovitis of a finger or toe is coupled with tenosynovitis, enthesitis and inflammation of intervening tissue to give a ‘sausage digit’ or dactylitis.

Large joints, such as the knee and ankle, may also be involved, sometimes with very large effusions.

PATTERNS OF PsA

Symmetrical polyarthritis occurs in about 25% of cases.It predominates in women and may strongly resemble RA, with symmetrical involvement of small and large joints in both upper and lower limbs.

Nodules and other extraarticular features of RA are absent and arthritis is generally less extensive and more benign.

Much of the hand deformity often results from tenosynovitis and soft tissue contractures.

PATTERNS OF PsA

Distal IPJ arthritisis an uncommon but characteristic pattern affecting men more often than women. It targets finger DIP joints and surrounding periarticular tissues, almost invariably with accompanying nail dystrophy.Psoriatic spondylitis presents a similar clinical picture to AS but with less severe involvement. It may occur alone or with any of the other clinical patterns described above and is typically unilateral or asymmetric in severity.

PATTERNS OF PsA

Arthritis mutilansis a deforming erosive arthritis targeting the fingers and toes that occurs in 5% of cases of PsA. Prominent cartilage and bone destruction results in marked instability. The encasing skin appears invaginated and ‘telescoped’ and the finger can be pulled back to its original length.Extra-articular features

Nail changes include pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis and horizontal ridging. They are found in 85% of those with PsA and only 30% of those with uncomplicated psoriasis, and can occur in the absence of skin disease.The characteristic rash of psoriasis may be widespread, or confined to the scalp, natal cleft and umbilicus, where it is easily overlooked.

Conjunctivitis can occur, whereas uveitis is mainly confined to HLAB27positive individuals with sacroiliitis and spondylitis.

Investigations

The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds.Autoantibodies are generally negative and acute phase reactants, such as ESR and CRP, are raised in only a proportion of patients with active disease.

Xrays may be normal or show erosive change with joint space narrowing. Features that favour PsA over RA include the characteristic distribution of proliferative erosions with marked new bone formation, absence of periarticular osteoporosis and osteosclerosis.

Imaging of the axial skeleton often reveals features similar to those in chronic reactive arthritis, with coarse, asymmetrical, nonmarginal syndesmophytes and asymmetrical sacroiliitis.

MRI and ultrasound with power Doppler are increasingly employed to detect synovial inflammation and inflammation at the entheses.

Management

Therapy with NSAID and analgesics may be sufficient to control symptoms in mild disease.Intraarticular steroid injections can control synovitis in problem joints.

Splints and prolonged rest should be avoided because of the tendency to fibrous and bony ankylosis.

Patients with spondylitis should be prescribed the same exercise and posture regime as in AS.

Management

Therapy with DMARDs should be considered for persistent synovitis unresponsive to conservative treatment. Methotrexate is the drug of first choice since it may also help skin psoriasis, but other DMARDs may also be effective, including sulfasalazine, ciclosporin and leflunomide.DMARD monitoring should take place with particular attention to liver function since abnormalities are common in PsA.

Hydroxychloroquine is generally avoided, as it can cause exfoliative skin reactions.

AntiTNF treatment should be considered for patients with active synovitis who respond inadequately to standard DMARDs. This is effective for both PsA and psoriasis.

Other biological treatments, such as ustekinumab, are emerging, which target the IL12/23 receptor. Ustekinumab is highly effective in the treatment of psoriatic skin disease and is often effective in PsA.

Management

The retinoid acitretin is effective for skin lesions and, anecdotally, may also help arthritis, but it is teratogenic so must be avoided in young women. It also causes mucocutaneous sideeffects, hyperlipidaemia, myalgias and extraspinal calcification.Photochemotherapy with methoxypsoralen and longwave ultraviolet light (psoralen +UVA, PUVA) is primarily used for skin disease, but can also help those with synchronous exacerbations of inflammatory arthritis.

Enteropathic arthritis

An acute inflammatory oligoarthritis occurs in around 10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% of those with Crohn’s disease. It predominantly affects the large lower limb joints (knees, ankles, hips) but wrists and small joints of the hands and feet can also be involved. The arthritis usually coincides with exacerbations of the underlying bowel disease, and sometimes is accompanied by aphthous mouth ulcers, iritis and erythema nodosum.

It improves with effective treatment of the bowel disease, and can be cured by total colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Enteropathic arthritis

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease may also develop sacroiliitis (16%) and AS (6%), which are clinically and radiologically identical to classic AS. These can predate or follow the onset of bowel disease and there is no correlation between activity of the spondylitis and bowel disease.The arthritis often remits with treatment of the bowel disease but DMARD and biological treatment is occasionally required.