Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

learning-topics

Rheumatology andbone disease

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Disorders of the musculoskeletal system affect all ages .

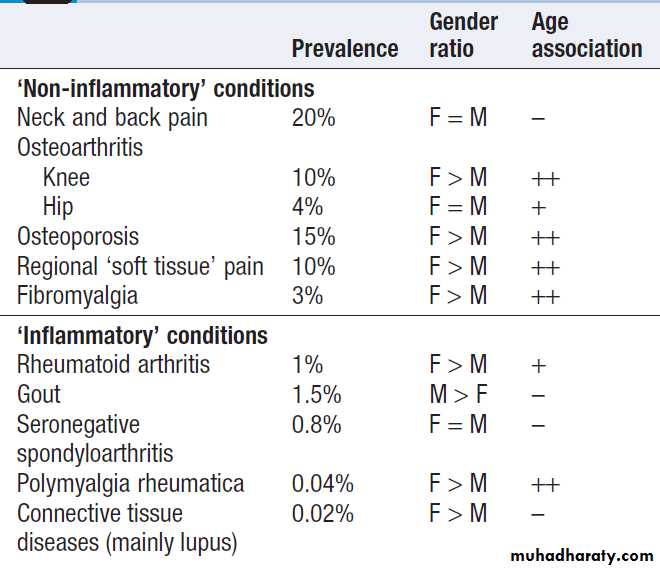

In the UK, about 25% of new consultations in general practice are for musculoskeletal symptoms. Arise from processes affecting bones, joints, muscles, or connective tissues such as skin and tendon. The principal manifestations are pain and impairment of locomotor function. It is more common in women and increase in frequency with increasing age. The two most common disorders are osteoarthritis and osteoporosis . Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis and affects up to 80% of people over the age of 75. Osteoporosis is the most common bone disease and affects 50% of women and 20% of men by their eighth decade. Account for one-third of physical disability at all ages.Relative prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders

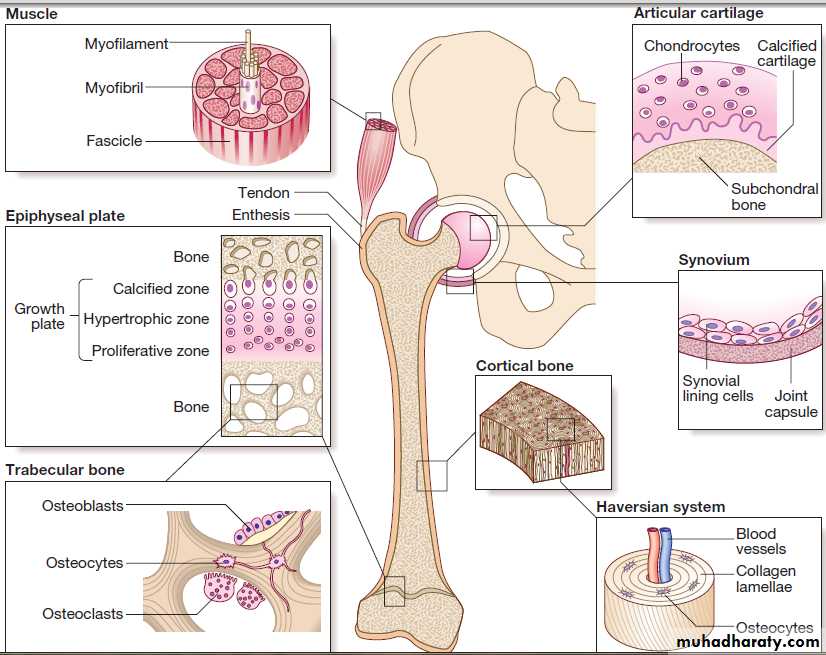

Structure of the major musculoskeletal tissues.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGYThe musculoskeletal system is responsible for movement of the body, protect internal organs, and acts as a reservoir for storage of calcium and phosphate in the regulation of mineral homeostasis.

Bone

Bones fall into two main types.

Flat bones, such as the skull, develop by intramembranous ossification, in which embryonic fibroblasts differentiate directly into bone within condensations of mesenchymal tissue during early fetal life.

Long bones, such as the femur and radius, develop

by endochondral ossification from a cartilage template.

During development, the cartilage is invaded by vascular

tissue containing osteoprogenitor cells and is gradually

replaced by bone from centres of ossification

situated in the middle and at the ends of the bone.

A thin remnant of cartilage called the growth plate or

epiphysis remains at each end of long bones, and

chondrocyte proliferation here is responsible for skeletal

growth during childhood and adolescence.

During puberty, the rise in levels of sex hormones halts cell division in the growth plate.

The cartilage remnant then disappears as the epiphysis fuses and longitudinal bone growth ceases.

The normal skeleton has two forms of bone tissue .

Cortical bone is formed from Haversian systems, comprising concentric lamellae of bone tissuesurrounding a central canal that contains blood vessels.

Cortical bone is dense and forms a hard envelope around

the long bones.

Trabecular or cancellous bone fills the centre of the bone and consists of an interconnecting meshwork of trabeculae, separated by spaces filled with bone marrow.

There are three main cell types in bone:

• Osteoclasts: multinucleated cells of haematopoieticorigin, responsible for bone resorption.

• Osteoblasts: mononuclear cells of mesenchymal

origin, responsible for bone formation.

• Osteocytes: these differentiate from osteoblasts during bone formation and become embedded in bone matrix. Osteocytes are responsible for sensing and responding to mechanical loading of the skeleton and play a critical role in regulating bone formation and bone resorption.

They also play a central role in regulating phosphate metabolism by producing the hormone fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), which acts on the kidney to promote phosphate excretion .

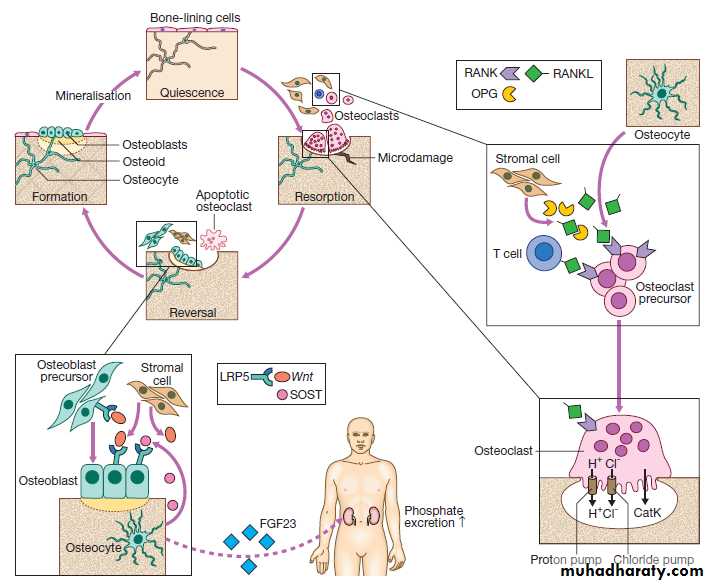

Fig. Regulation of bone remodelling. Bone is renewed and repaired during the bone remodelling cycle, in which old and damaged bone is removed by osteoclasts and replaced by osteoblasts. Osteocytes play a central role in bone remodelling by secreting RANKL, which promotes osteoclast differentiation and activity by binding to RANK. Osteocytes regulate bone formation by producing SOST, which binds to the LRP5 receptor and prevents its activation by members of the Wnt family.

Osteocytes also regulate phosphate homeostasis by producing fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), which is a circulating hormone that acts on the kidney to promote phosphate excretion. (CatK = cathepsin K; LRP5 = lipoprotein receptor protein 5; OPG = osteoprotegerin; RANK = receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B; RANKL = RANK ligand; SOST = sclerostin).

Bone matrix and mineral

The most abundant protein of bone is type I collagen,which is formed from two α1 peptide chains and one α2

chain wound together in a triple helix. Type I collagen

is proteolytically processed inside the cell before being

laid down in the extracellular space, releasing propeptide

fragments that can be used as biochemical markers

of bone formation .

Subsequently, the collagen fibrils become ‘cross-linked’ to one another by pyridinium molecules, a process that enhances bone strength.

When bone is broken down by osteoclasts, the crosslinks are released, providing biochemical markers of bone resorption.

Bone is normally laid down in an orderly fashion, but when bone turnover is high, as in Paget’s disease or severe hyperparathyroidism, it is laid down in a chaotic pattern, giving rise to ‘woven bone’, which is mechanically weak. Bone matrix also contains growth factors, other structural proteins and proteoglycans, thought to be involved in helping bone cells attach to bone matrix and in regulating bone cell activity. The other major component of bone is mineral, comprised of calcium and phosphate crystals deposited between the collagen fibrils in the form of hydroxyapatite [Ca10 (PO4)6 (OH)2]. Mineralisation is essential for bone’s rigidity and strength, but over-mineralisation can increase brittleness, which contributes to bone fragility in diseases like osteogenesis imperfecta .

Bone remodelling

Bone remodelling is required for renewal and repair ofthe skeleton throughout life . It starts with the attraction of osteoclast precursors in peripheral blood to the target site, probably by local release of chemotactic factors from areas of microdamage.

The osteoclast precursors differentiate into mature osteoclasts in response to RANKL, which is produced by

osteocytes, activated T cells and bone marrow stromal

cells. RANKL activates the RANK receptor, which is

expressed on osteoclasts and precursors. This is blocked

by osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor for RANKL

that inhibits osteoclast formation.

Mature osteoclasts attach to the bone surface by a tight sealing zone, and secrete hydrochloric acid and proteolytic enzymes such as cathepsin K into the space underneath. The acid dissolves the mineral and cathepsin K degrades collagen.

When resorption is complete, osteoclasts undergo programmed cell death, and bone formation begins with

the attraction of osteoblast precursors to the resorption

site. These differentiate into mature osteoblasts, which

deposit new bone matrix in the resorption lacuna, until

the hole is filled. Some osteoblasts become trapped in

bone matrix and differentiate into osteocytes. These act as biomechanical sensors and produce several molecules that influence bone remodelling and phosphate metabolism.

Bone formation is stimulated by Wnt proteins, which bind to and activate lipoprotein-related receptor protein 5 (LRP5), expressed on osteoblasts. This process is inhibited by SOST, which is produced by osteocytes .

Initially, the newly formed bone matrix (osteoid) is uncalcified but subsequently becomes mineralized to form mature bone. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), produced by osteoblasts, plays an important role in bone mineralisation by degrading pyrophosphate, an inhibitor of mineralisation.

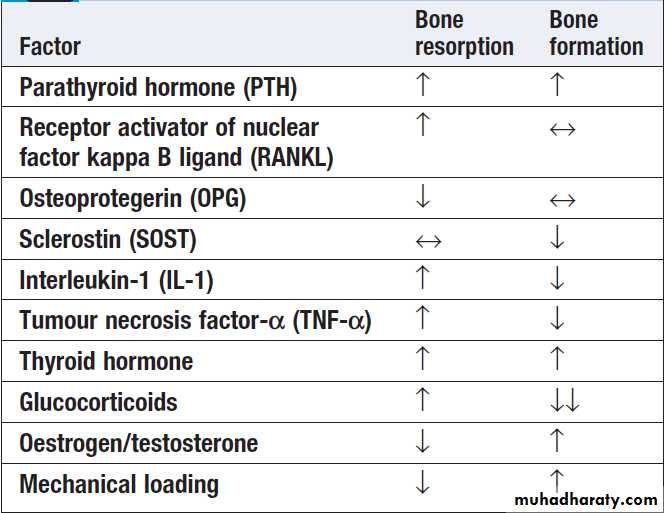

Bone remodelling is regulated by circulating hormones such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) and oestrogen, and locally produced factors such as cytokines .

Regulators of bone remodelling

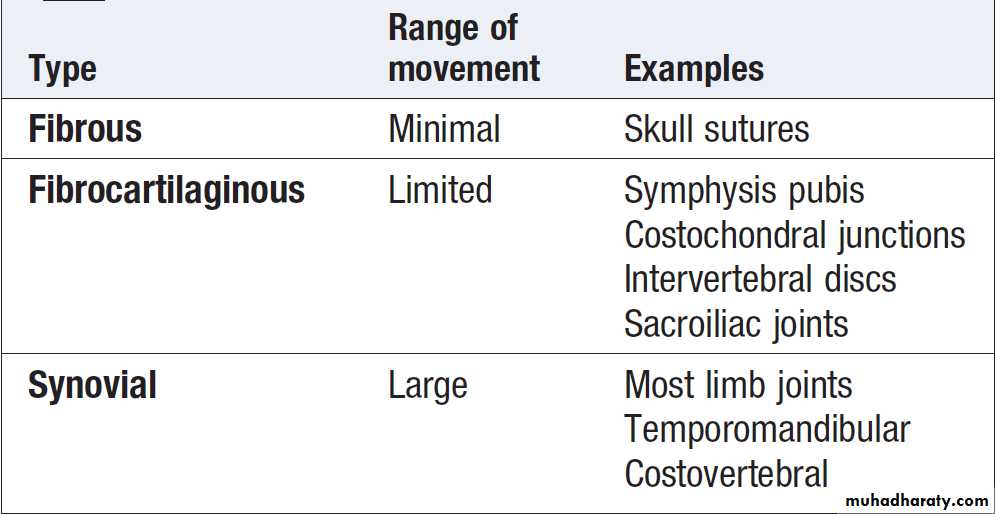

Types of joint

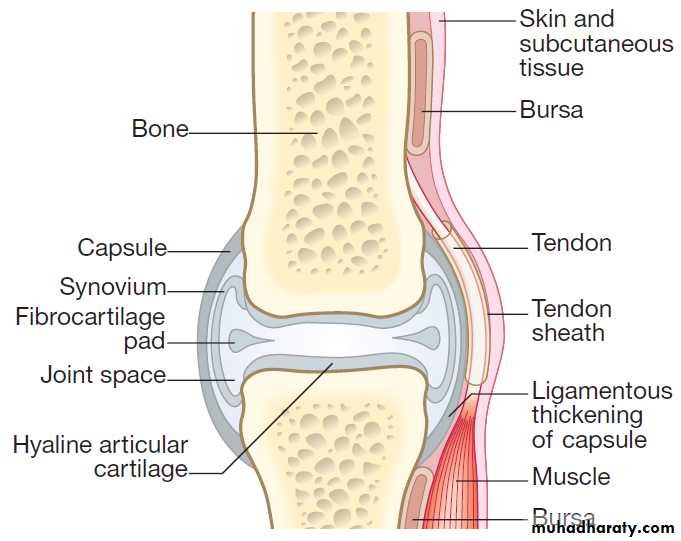

Structure of a synovial joint

Ultrastructure of articular cartilage

JointsBones are linked by joints. There are three main subtypes:

fibrous, fibrocartilaginous and synovial .

Fibrous and fibrocartilaginous joints

These comprise a simple bridge of fibrous or fibrocartilaginous tissue joining two bones together where there is little requirement for movement. The intervertebral disc is a special type of fibrocartilaginous joint in which an amorphous area, called the nucleus pulposus, lies in the centre of the fibrocartilaginous bridge. The nucleus has a high water content and acts as a cushion to improve the disc’s shock-absorbing properties.

Synovial joints

Complex structures containing several cell types, theseare found where a wide range of movement is needed.

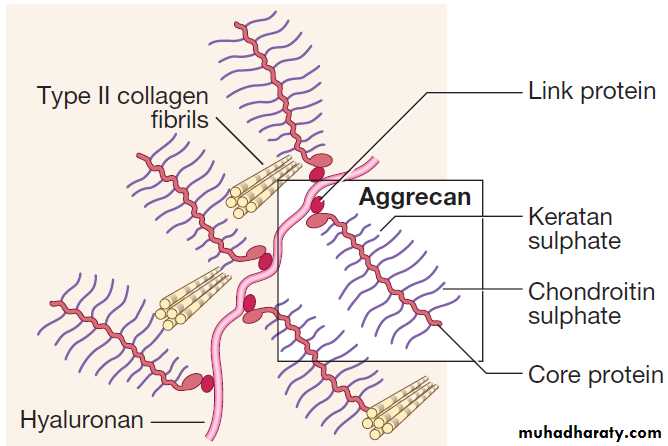

Articular cartilage

This avascular tissue covers the bone ends in synovial

joints. Cartilage cells (chondrocytes) are responsible for

synthesis and turnover of cartilage, which consists of a

mesh of type II collagen fibrils that extend through a

hydrated ‘gel’ of proteoglycan molecules. The most important proteoglycan is aggrecan, which consists of a

core protein to which several glycosaminoglycan (GAG)

side-chains are attached . The expansive force of the hydrated aggrecan, combined with the restrictive strength of the collagen mesh, gives articular cartilage excellent shock-absorbing properties.

With ageing, the concentration of chondroitin sulphate

decreases, whereas that of keratan sulphate

increases, resulting in reduced water content and shockabsorbing properties. These changes differ from those found in osteoarthritis , where there is abnormal

chondrocyte division, loss of proteoglycan from matrix

and an increase in water content. Cartilage matrix is

constantly turning over and in health there is a perfect

balance between synthesis and degradation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1)

and tumour necrosis factor (TNF), stimulate production

of aggrecanase and metalloproteinases, which contribute

to cartilage degradation in inflammatory arthritis.

Synovial fluid

The surfaces of articular cartilage are separated bya space filled with synovial fluid, a viscous liquid

that lubricates the joint. It is an ultrafiltrate of plasma,

into which synovial cells secrete hyaluronan and

proteoglycans.

Intra-articular discs

Some joints contain fibrocartilaginous discs within the

joint space that act as shock absorbers. The most clinically

important are the menisci of the knee. These are

avascular structures that remain viable by diffusion of

oxygen and nutrients from the synovial fluid.

The synovial membrane, joint capsule and bursae

The bones of synovial joints are connected by the

joint capsule, a fibrous structure richly supplied with

blood vessels, nerves and lymphatics, which encases the

joint. Ligaments are discrete, regional thickenings of

the capsule that act to stabilise joints . The inner surface of the joint capsule is the synovial membrane, comprising an outer layer of blood vessels and loose connective tissue that is rich in type I collagen, and an inner layer 1–4 cells thick consisting of two main cell types.

Type A synoviocytes are phagocytic cells derived from the monocyte/macrophage lineage and are responsible for removing particulate matter from the joint cavity; type B synoviocytes are fibroblast-like cells that secrete synovial fluid. Most inflammatory and degenerative joint diseases associate with thickening of the synovial membrane and infiltration by lymphocytes, polymorphs and macrophages.

Bursae are hollow sacs lined with synovium and

contain a small amount of synovial fluid.

They help tendons and muscles move smoothly in relation to bones and other articular structures.

Skeletal muscle

Skeletal muscles are responsible for body movementsand respiration. Muscle consists of bundles of cells

(myocytes) embedded in fine connective tissue containing

nerves and blood vessels. Myocytes are large,

elongated, multinucleated cells formed by fusion of

mononuclear precursors (myoblasts) in early embryonic

life. The nuclei lie peripherally and the centre of the cell

contains actin and myosin molecules, which interdigitate

with one another to form the myofibrils that are

responsible for muscle contraction.

The molecular Mechanisms of skeletal muscle contraction are the same as for cardiac muscle .

Myocytes contain many mitochondria that provide the large amounts of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) necessary for muscle contraction, and are rich in the protein myoglobin, which acts as a reservoir for oxygen during contraction.

Tendons are tough, fibrous structures that attach muscles to a point of insertion on the bone surface called the enthesis.

INVESTIGATION OF MUSCULOSKELETAL DISEASE

Clinical history and examination usually provide sufficientinformation for the diagnosis and management of most musculoskeletal diseases. Investigations are helpful in confirming the diagnosis, assessing disease activity and indicating prognosis.

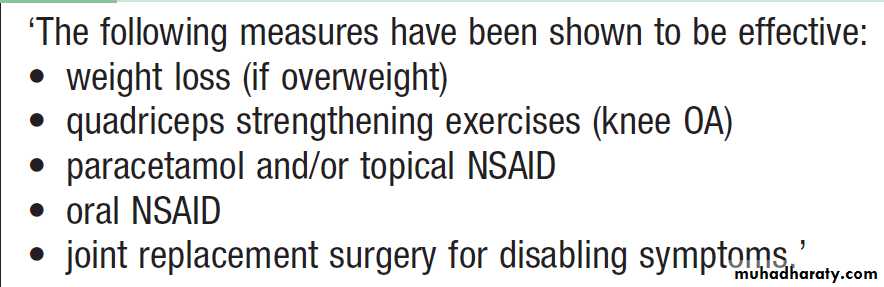

Joint aspiration

Joint aspiration with examination of synovial fluid (SF)

is pivotal in patients suspected of having septic arthritis,

crystal arthritis or intra-articular bleeding. It should be

done in all patients with acute monoarthritis, and samples sent for microbiology and clinical chemistry. It is possible to obtain SF by aspiration from most peripheral joints, and only a small volume is required for diagnostic purposes.

Normal SF is present in small volume, and is clear and either colourless or pale yellow with a high viscosity. It contains few cells. With joint inflammation, the volume increases, the cell count and the proportion of neutrophils rise (causing turbidity), and the viscosity reduces (due to enzymatic degradation of hyaluronan and aggrecan).

Turbid fluid with a high neutrophil count occurs in sepsis, crystal arthritis and reactive arthritis. High concentrations of urate crystals or cholesterol can make SF appear white. Non-uniform blood-staining usually reflects needle trauma to the synovium. Uniform blood-staining is most commonly due to a bleeding diathesis, trauma or pigmented villonodular synovitis , but can occur in severe synovitis.

A lipid layer floating above blood-stained

fluid is diagnostic of intra-articular fracture and iscaused by release of bone marrow fat into the joint.

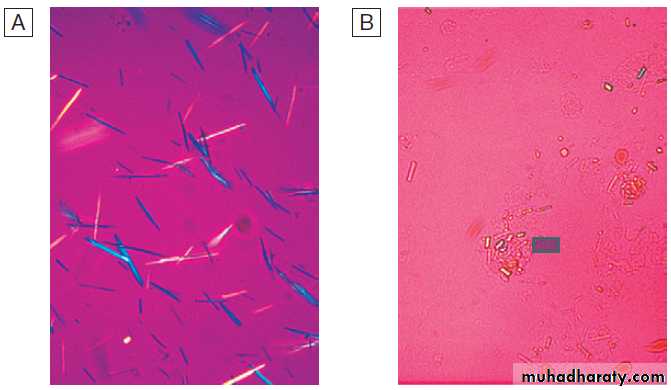

Crystals can be identified by compensated polarised

light microscopy of fresh SF (to avoid crystal dissolution

and post-aspiration crystallisation). Urate crystals are

long and needle-shaped, and show a strong light intensity

and negative birefringence . Calcium pyrophosphate crystals are smaller, rhomboid in shape

and usually less numerous than urate, and have weak

intensity and positive birefringence .

Compensated polarised light microscopy of synovial

fluids (× 400).A Monosodium urate crystals showing bright negative birefringence under polarised light and needle-shaped morphology.

B Calcium pyrophosphate crystals showing weak positive birefringence under polarised light and are few in number. They are more difficult to

detect than urate crystals.

Imaging

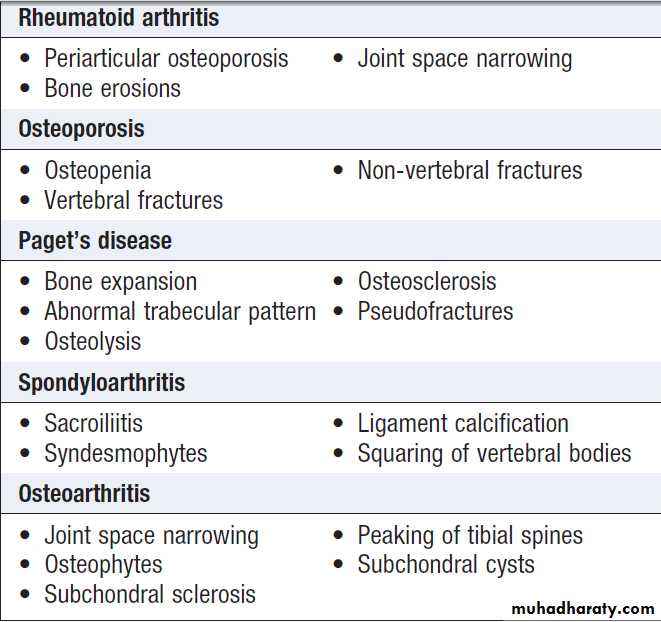

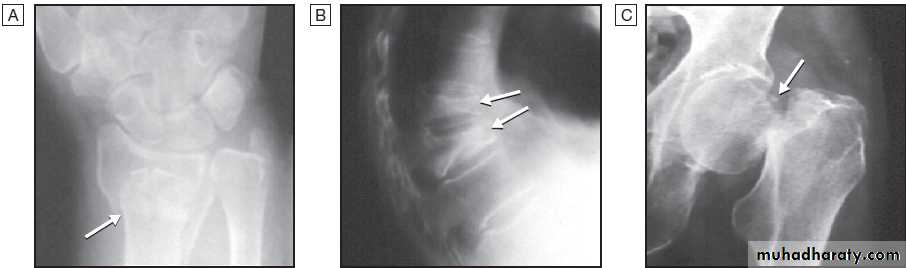

Plain radiographyShow changes of many bone and joint diseases . Radiographs are of diagnostic value in osteoarthritis

(OA), where they demonstrate joint space narrowing

that tends to be focal rather than widespread, as in

inflammatory arthritis. Other features of OA detected on

X-ray include osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, bone

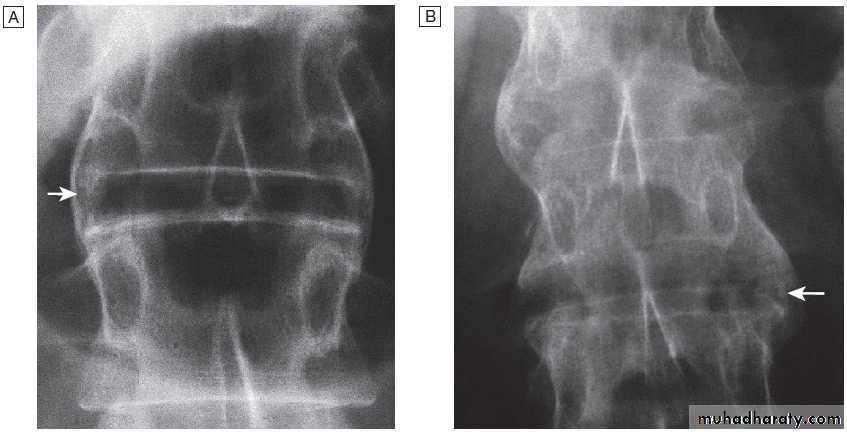

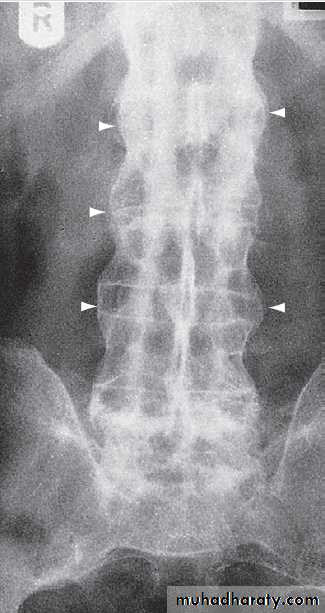

cysts and calcified loose bodies within the synovium . Radiographs may show erosions and sclerosis of the sacroiliac joints and syndesmophytes in the spine in seronegative spondyloarthritis. In peripheral joints, so-called proliferative erosions, associated with new bone formation and a periosteal reaction, may be observed.

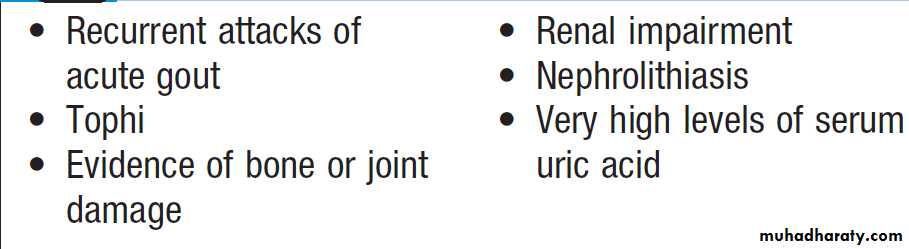

In tophaceous gout, well-defined punched-out erosions may occur .

Calcification of cartilage, tendons and soft tissues or muscle may occur in chondrocalcinosis , calcific periarthritis and connective tissue diseases. Radiographs are of limited value in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) since features such as erosions, joint space narrowing and periarticular osteoporosis may only be detectable after several months or even years.Early evidence of articular damage in RA is more usually obtained using MRI or ultrasonography.

X-ray abnormalities in selected

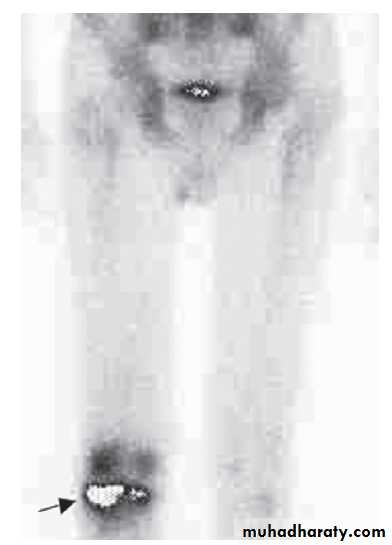

rheumatic diseasesRadionuclide bone scan

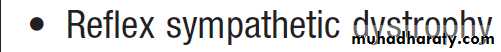

This is useful in patients suspected of having metastatic bone disease and Paget’s disease. It involves gamma-camera imaging following an intravenous injection of 99mTc-bisphosphonate. Early post-injection images reflect vascularity and can show increased perfusion of inflamed synovium, Pagetic bone, or primary or secondary bone tumours. Delayed images taken a few hours later reflect bone remodelling as the bisphosphonate localises to sites of active bone turnover. Scintigraphy has a high sensitivity for detecting important bone and joint pathology that is not apparent on plain X-rays . Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) combines radionuclide imaging with computed tomography. It can provide accurate anatomical localization of abnormal tracer uptake within the bone and is of particular value in the assessment of patients with chronic low back pain of unknown cause.Conditions detected by isotope bone scanning

Magnetic resonance imaging

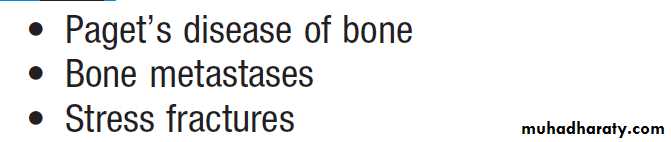

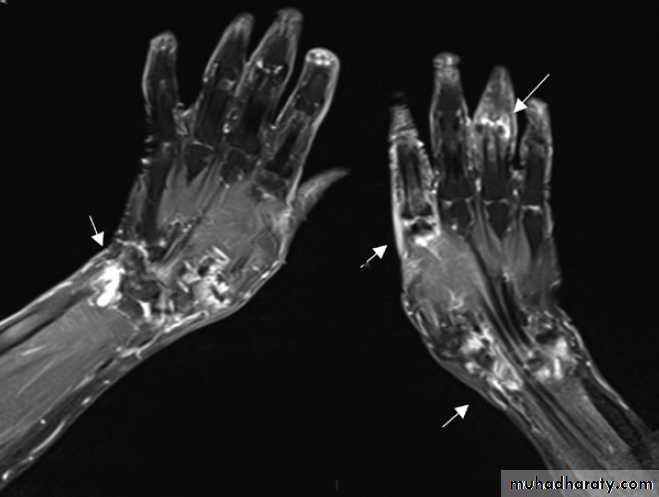

Gives detailed information on anatomy, allowing three-dimensional visualization of bone and soft tissues that cannot be adequately assessed by plain X-rays. The technique is valuable in the assessment and diagnosis of many musculoskeletal diseases . T1-weighted sequences are useful for defining anatomy, whereas T2-weighted sequences are useful for assessing tissue water content, which is often increased in synovitis and other inflammatory disorders . Contrast agents, such as gadolinium, can be administered to increase sensitivity in detecting erosions and synovitis.Conditions detected by magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance image showing synovitis. Coronal

fat-saturated post-contrast T1-weighted image shows extensiveenhancement consistent with synovitis (white areas, arrowed) in both wrists

and at the second metacarpophalangeal joint and proximal interphalangeal

joints of the right hand.

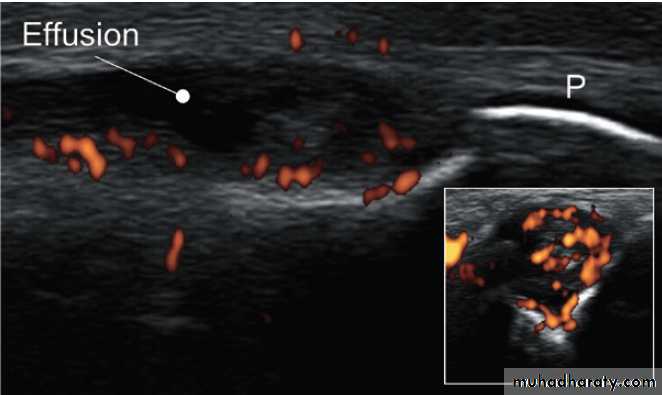

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a useful investigation for confirmationof small joint synovitis and erosion, for anatomical

confirmation of periarticular lesions, and for guided

aspiration and injection of joints and bursae. Ultrasound

is more sensitive than clinical examination for the

detection of early synovitis and is used increasingly

in the diagnosis and assessment of patients with suspected

inflammatory arthritis. In addition to locating

synovial thickening and effusions, ultrasound can detect

increased blood flow within synovium using power

Doppler imaging, an option that is available on most

modern ultrasound machines .

Ultrasound image showing synovitis. Lateral image of a metacarpophalangeal joint in inflammatory arthritis. The periosteum (P) of the phalanx shows as a white line. The dark, hypo-echoic area indicates

an effusion. The coloured areas demonstrated by power Doppler indicate

increased vascularity. The inset shows a transverse image of the same joint.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) can be used in the assessmentof patients with bone and joint disease but

has largely been superseded by MRI, which gives

better visualisation of soft tissue structures. CT may be

used when MRI is contraindicated, or for evaluation

of articular regions in which an adjacent joint replacement

creates image artefacts on MRI.

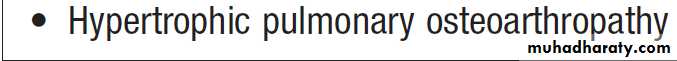

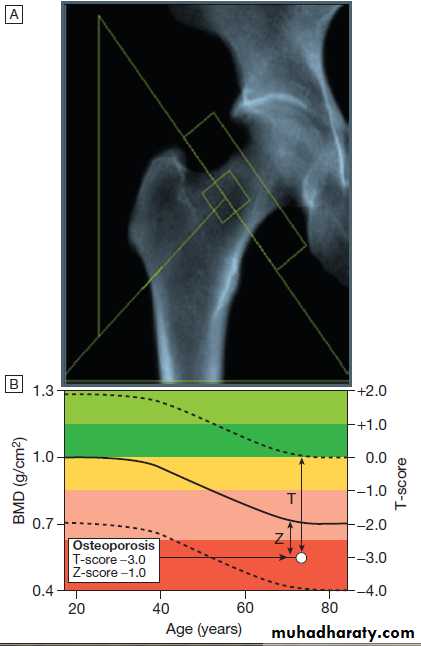

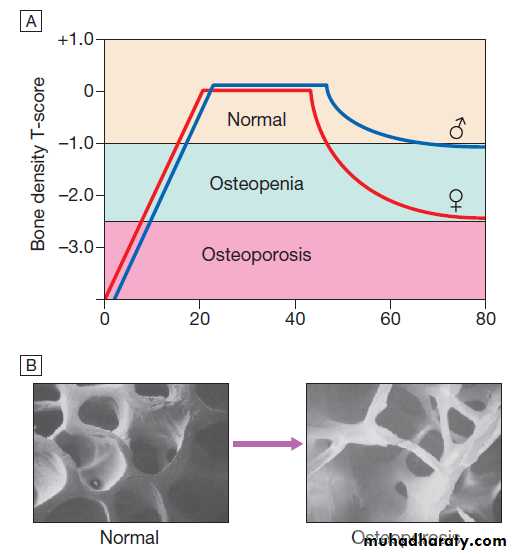

Bone mineral density (BMD)

BMD measurements play a key role in the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. The technique of choice is dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), which is usually performed at the lumbar spine and hip.This technique works on the principle that calcium in bone attenuates passage of X-ray beams through the

tissue in proportion to the amount of mineral present. The greater the amount of bone mineral present, the

higher the BMD value. Most DEXA scanners give a BMD

readout expressed as grams of hydroxyapatite/cm2, and

as a T-score and Z-score value. Osteoporosis is defined by a T-score value of 2.5 or below (shaded red in the figure), whereas osteopenia is diagnosed when the T-score lies between −1.0 and −2.5 (shaded pink).

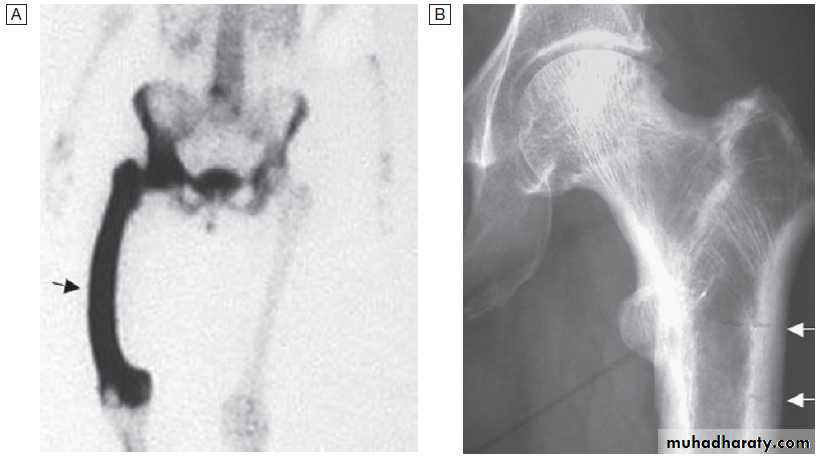

Fig. Typical output from a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

(DEXA) scanner.A DEXA scan of the hip.

B Bone mineral density

(BMD) values plotted in g/cm2 (left axis) and as the T-score values (right axis). The solid line represents the population average plotted against age,

and the interrupted lines are ± 2 standard deviations from the average.

The patient shown, aged 72, has an osteoporotic T-score of −3.0 but a Z-score of −1.0, which is within the ‘normal range’ for that age, reflecting the fact that bone is lost with age.

Blood tests

HaematologyAbnormalities in the full blood count (FBC) often occur

in inflammatory rheumatic diseases but changes are

usually non-specific. Examples include neutrophilia in

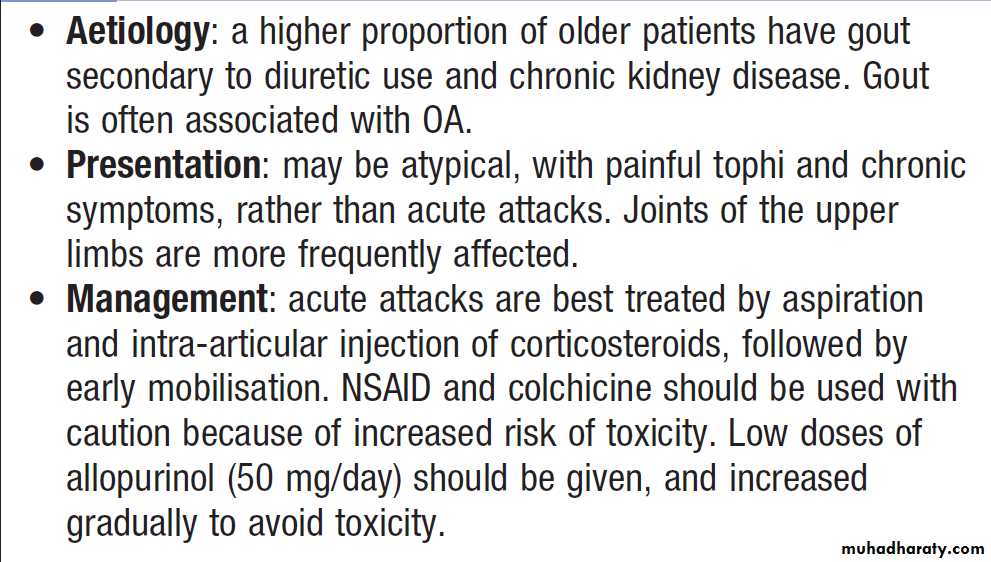

vasculitis, acute gout and sepsis; neutropenia in lupus;

and a raised ESR in many inflammatory diseases. Reduced levels of haemoglobin are a common and important finding in a range of rheumatological disorders. Many disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) cause marrow toxicity and require regular monitoring of the FBC.

Biochemistry

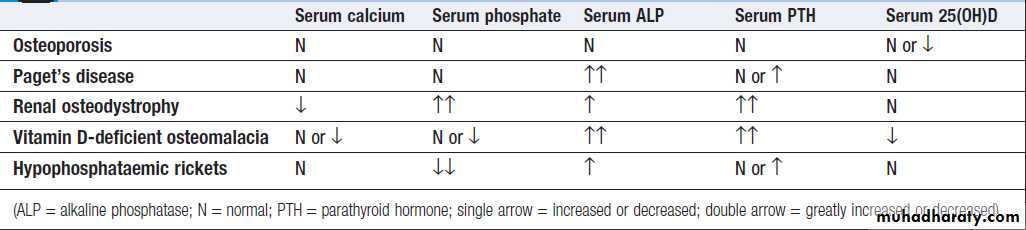

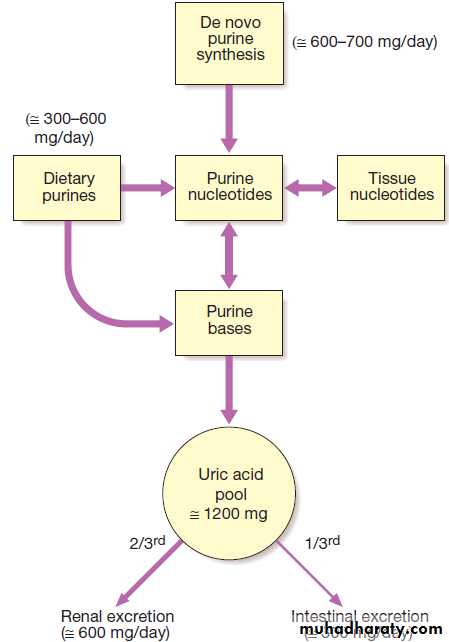

Routine biochemistry is useful for assessing metabolicbone disease, muscle diseases and gout. Several bone

diseases, including Paget’s disease, renal bone disease

and osteomalacia, give a characteristic pattern that can

be helpful diagnostically (Box). Serum levels of uric

acid are usually raised in gout but a normal level does

not exclude it, especially during an acute attack, when

urate levels temporarily fall. Equally, an elevated serum

uric acid does not confirm the diagnosis, since most

Hyperuricaemic people never develop gout. Levels of

C-reactive protein (CRP) are a useful marker of infection

and inflammation, and are more specific than the ESR.

An exception is in connective tissue diseases such as

systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis,

where CRP may be normal but ESR raised in active

inflammatory disease. Accordingly, an elevated CRP in

a patient with lupus or scleroderma suggests an Intercurrent illness such as sepsis rather than active disease.

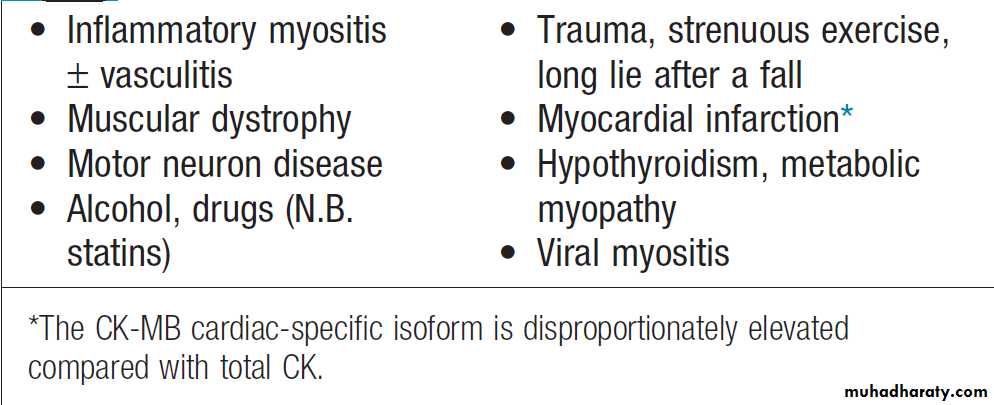

Serum creatine kinase (CK) levels are useful in the diagnosis of myopathy or myositis, but specificity and sensitivity are poor and raised levels may occur in some conditions . Biochemical monitoring of renal and hepatic function is important in patients on DMARD therapy.

Biochemical abnormalities in bone disease

Causes of an elevated serum creatine kinase

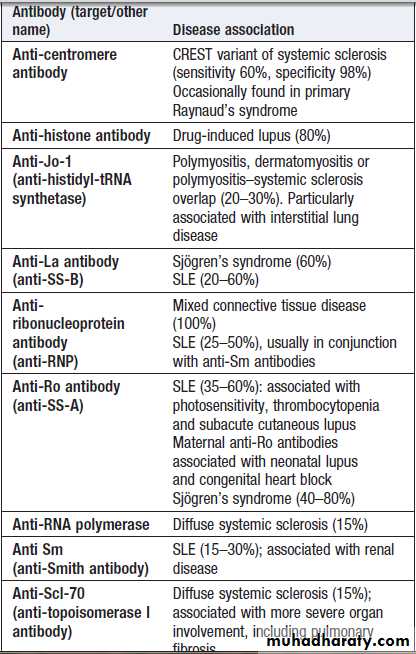

AutoantibodiesAutoantibody tests are widely used in the diagnosis of

rheumatic diseases. False-positive results are common

but high antibody titres or concentrations are generally

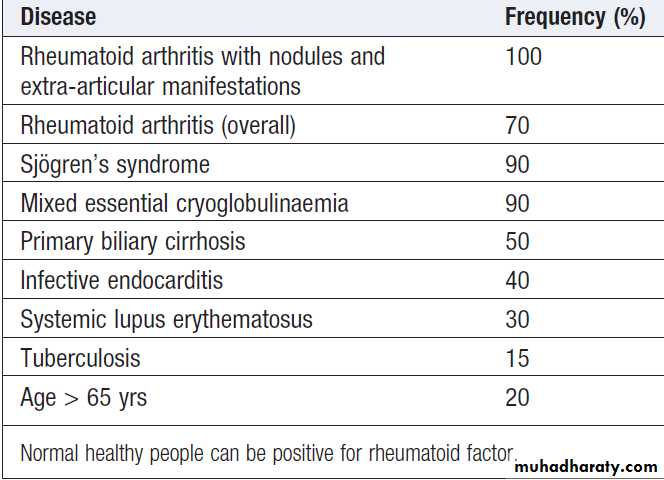

of greater clinical significance. Whatever test is used, the results must be interpreted in light of the clinical picture. Rheumatoid factor (RF)

Antibody directed against the Fc fragment of human immunoglobulin. IgM RF is usually measured, although different methodologies allow measurement of IgG and IgA RFs too. Positive RF occurs in a wide variety of diseases and some normal particularly with increasing age. Although the specificity is poor, about 70% with RA test positive. High RF titres are associated with more severe disease and extra-articular disease.

Conditions associated with a positive rheumatoid factor

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA)ACPA have similar sensitivity to RF for RA (70%) but much higher specificity (> 95%), and are increasingly being used in preference to RF in the diagnosis of RA. ACPA are associated with more severe disease progression, and can be detected in asymptomatic patients several years before the development of RA. Their pathological role is still debated but it is likely that they amplify the synovial response at an inflammatory stimulus.

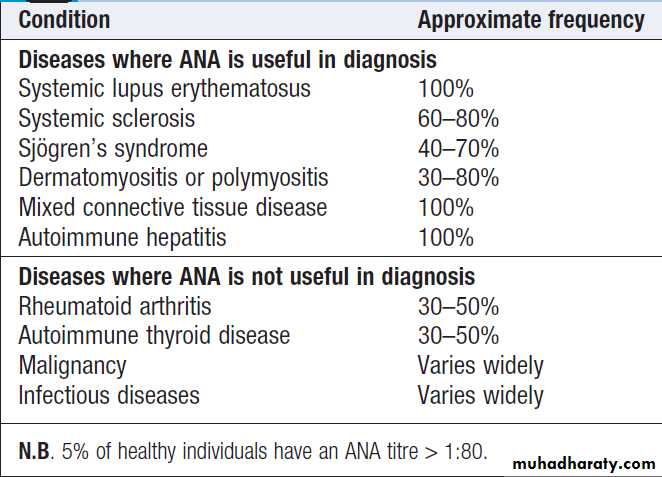

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

Directed against one or more components of the cell nucleus. They occur in many inflammatory rheumatic diseases but are also found at low titre in normal individuals and in other diseases.

High titres of ANA are of greater diagnostic significance but circulating levels are not associated with disease severity or activity. The most common indication for ANA testing is in patients suspected of SLE or connective tissue diseases. ANA has high sensitivity for SLE (virtually 100%) but low specificity (10– 40%). A negative ANA virtually excludes SLE but a positive result does not confirm it. Anti-DNA antibodies bind to double-stranded DNA and are highly specific for SLE (95%) but sensitivity is poor (30%). They can be useful in disease monitoring

since very high titres are associated with more severe

disease. Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) act as markers for certain CT diseases and some complications of SLE, but poor sensitivity and specificity.

For example, antibodies to Sm are found in a minority of SLE patients but are associated with renal involvement.

Antibodies to Ro occur in SLE and in Sjِgren’s syndrome (in association with anti-La antibodies), and are associated with a photosensitive rash and congenital heart block. Antibodies to ribonuclear protein (RNP) occur in SLE

and also in mixed connective tissue disease, where

features of lupus, myositis and systemic sclerosis

coexist.

Anti-topoisomerase 1 (also termed Scl-70) antibodies occur in diffuse systemic sclerosis, whereas anti-centromere antibodies are more specific for limited systemic sclerosis.

Conditions associated with a positive antinuclear antibody

Conditions associated with antibodies to

extractable nuclear antigensAntiphospholipid antibodies

Bind to a number of phospholipid binding proteins, but the most clinically relevant are those that target beta2-glycoprotein 1 (β2GP1). They may be detected in SLE and other CT diseases or can be present in isolation or in the antiphospholipid antibody syndromeAntineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are IgG

antibodies directed against the cytoplasmic constituents

of granulocytes and are useful in the diagnosis and

monitoring of systemic vasculitis. These antibodies are not specific for vasculitis and positive results may be found in autoimmune liver disease, malignancy, infection (bacterial and HIV), inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE and pulmonary fibrosis.

Tissue biopsy

Synovial biopsy can be useful in chronic inflammatory monoarthritis or tenosynovitis to rule out chronic infectious causes, especially mycobacterial infections. Characteristic changes on MRI can obviate the need for biopsy in many cases of suspected tumour. synovial biopsy can be obtained arthroscopically (by conventional meansor via use of needle arthroscope) or using ultrasound

guidance under local anaesthetic. Temporal artery biopsy can be of value in suspected of having temporal arteritis, but a negative result does not exclude the diagnosis. Biopsies of affected tissues, such as skin, lung, nasopharynx, gut, kidney and muscle, can be of value in the diagnosis of systemic vasculitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis).

Muscle biopsy plays an important role in the investigation

of myopathy and inflammatory myositis. It is usually taken from the quadriceps or deltoid through a small skin incision under local anaesthetic. Since myositis can be patchy in nature, MRI is sometimes used to localise the best site. Repeat biopsies are sometimes used to monitor the response to treatment. Bone biopsy is occasionally required where noninvasive tests give inconclusive and in the diagnosis of infiltrative disorders, chronic infections and malignancy. If osteomalacia, is suspected, the biopsy can be taken from the iliac crest using trephine needle under local anaesthetic. For focal lesions, the biopsy

should be taken under X-ray guidance or at open

surgery, from an affected site.

Electromyography

Electromyography is of value in the investigationof suspected myopathy and inflammatory myositis,

when it shows the diagnostic triad of:

• spontaneous fibrillation

• short-duration action potentials in a polyphasic

disorganised outline

• repetitive bouts of high-voltage oscillations on

needle contact with diseased muscle.

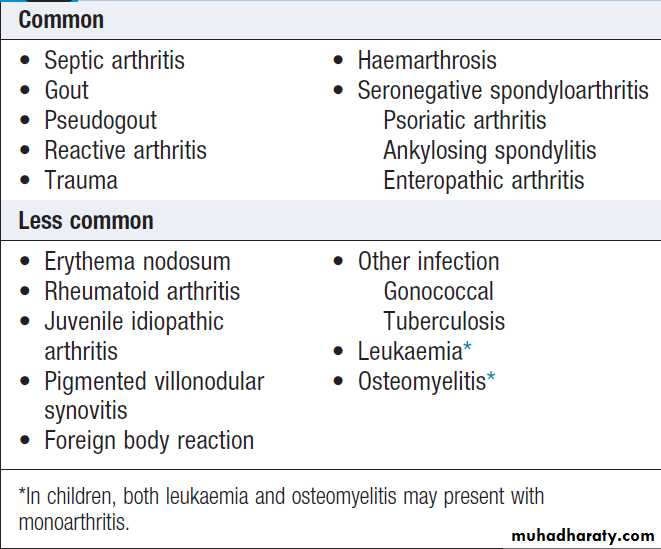

Causes of acute monoarthritis

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN MUSCULOSKELETAL DISEASEAcute monoarthritis

Sudden pain and swelling in a single joint. The most important are crystal, sepsis and reactive arthritis.

Clinical assessment

The clinical history, pattern of joint involvement, speed

of onset, and age and gender of the patient all give clues

to the most likely diagnosis. Reactive arthritis is the most common cause in young men, gout in middle-aged

men and pseudogout in older women.

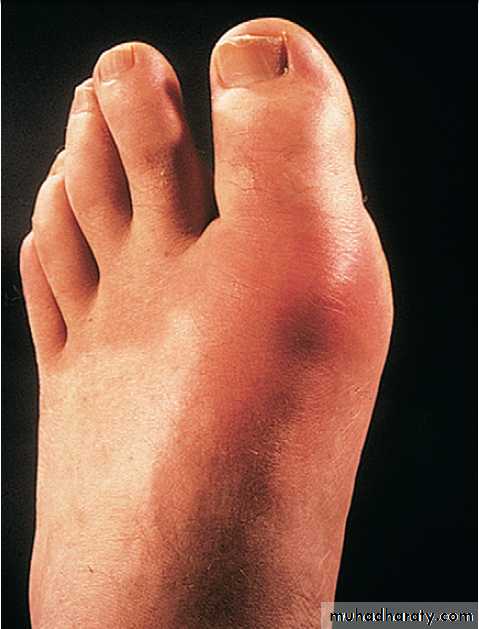

Gout classically affects the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, whereas the wrist and shoulder are typical sites for pseudogout.

A very rapid onset (6–12 hours) is suggestive of gout or pseudogout; joint sepsis develops more slowly and continues to progress until treated. Haemarthrosis typically causes a large effusion, in the absence of periarticular swelling or skin change.A previous diarrhoeal illness or recent sexual contact suggests reactive, whereas intercurrent illness, dehydration or surgery may act as a trigger for crystal-induced arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis seldom presents with monoarthritis

and a sudden increase in pain and swelling involving

a single joint in pre-existing RA is strongly suggestive of sepsis. Osteoarthritis can present with pain and stiffness affecting a single joint, but the onset is gradual and there is seldom evidence of significant joint swelling.

Investigations

Aspiration of the affected joint is mandatory. The fluidshould be sent for culture and Gram stain to seek the

presence of organisms, and should be checked by microscopy for crystals. Blood cultures should also be

taken in patients suspected of having septic arthritis.

CRP levels and ESR are raised in sepsis, crystal arthritis

and reactive arthritis, and this can be useful in assessing

the response to treatment.

Serum uric acid measurements may be raised in gout but a normal level does not exclude the diagnosis.

Management

If there is any suspicion of sepsis,IV antibiotics should be given promptly, pending the results of cultures. Otherwise, management should be directed towards the cause.

Causes of polyarthritis

Causes of polyarthritis – cont’d

Less common

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Symmetrical, small and large joints, upper and lower limbs

Chronic gout Affects distal more than proximal joints, history of acute attacks

Chronic sarcoidosis

Symmetrical, small and large joints

Polymyalgia rheumatic

Symmetrical, small and large joints

Rare

Systemic sclerosis and polymyositis

Small and large joints

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

Small joints, clubbing

Haemochromatosis

Small and large joints

Acromegaly

Mainly large joints and spine

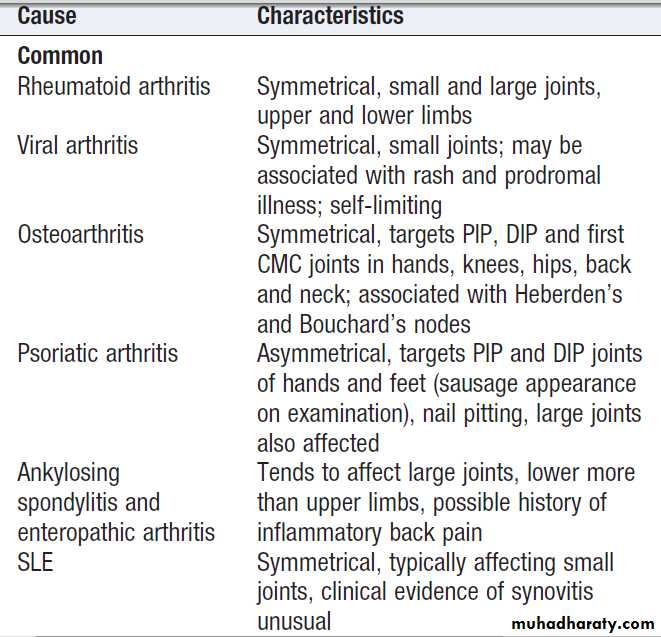

Polyarthritis

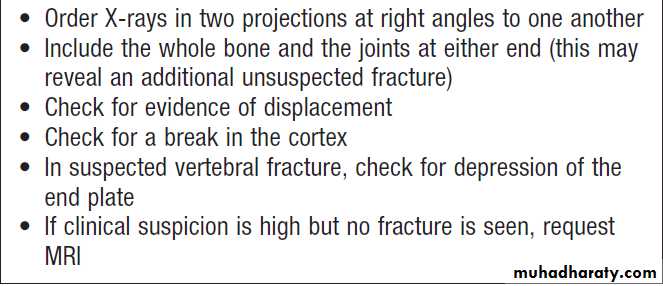

This term is used to describe pain and swelling affecting five or more joints or joint groups.Clinical assessment

The hallmarks of inflammatory arthritis are early morning stiffness and worsening of symptoms with inactivity, along with synovial swelling and tenderness on

examination. The most important diagnosis to consider is rheumatoid arthritis, which is characterised by symmetrical involvement of the small joints of the hands and feet, often in association with other joints. Viral arthritis should also be considered. This presents with an acute symmetrical inflammatory polyarthritis affecting small and large joints of upper and lower limbs, often with a rash.

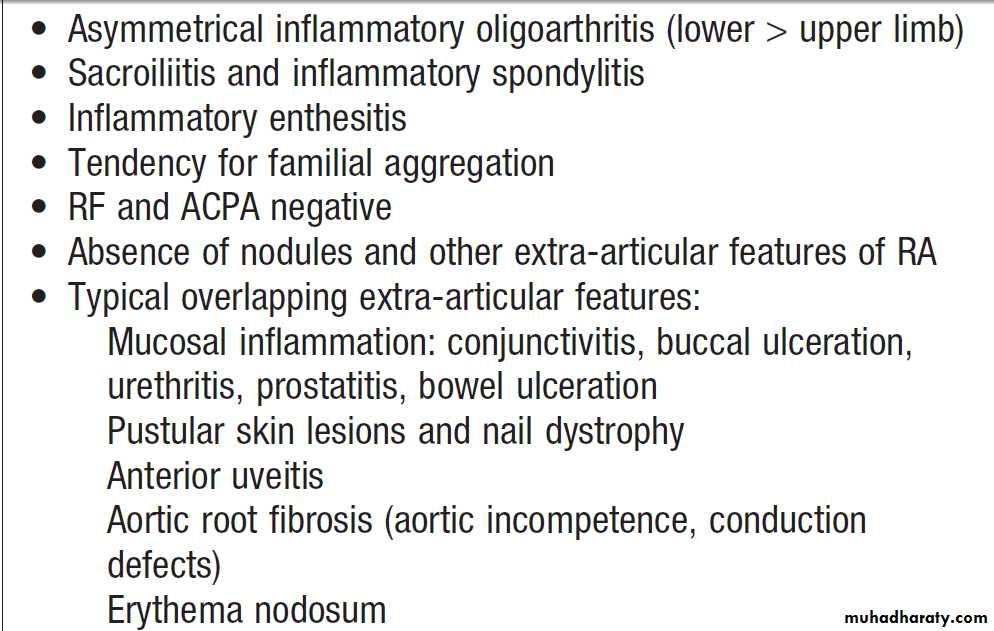

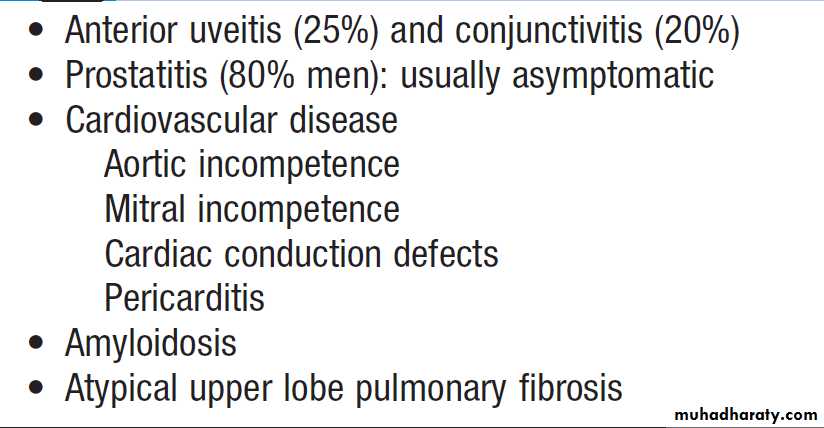

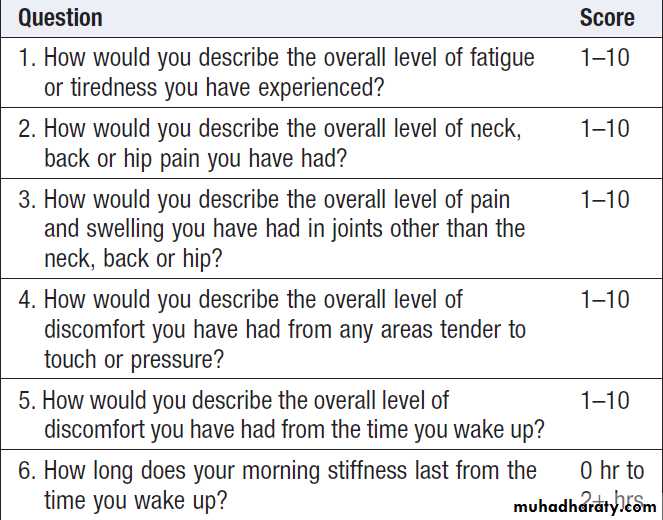

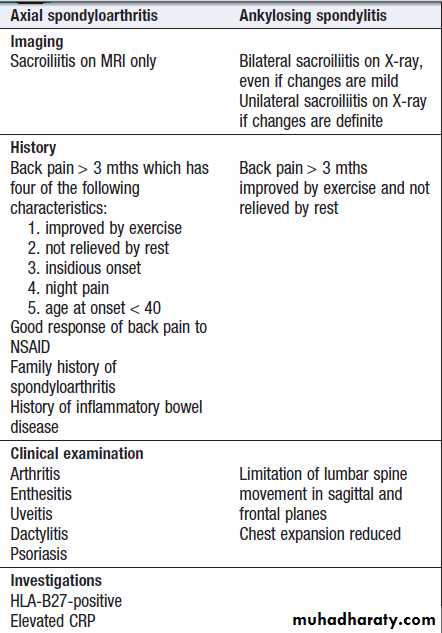

The pattern of involvement can be helpful in reaching a diagnosis . Asymmetry, lower limb predominance and greater involvement of large joints are characteristic of seronegative spondyloarthritis. Other extra-articular features may also be present, giving a clue to the diagnosis. In psoriatic arthritis, the small joints of the hand and feet are often affected, with involvement of the proximal and distal interphalangeal (PIP and DIP) joints, as opposed to the MCP and PIP joints in RA.

The pattern of involvement also tends to be asymmetrical in psoriatic arthritis, and other clues such as nail pitting and a rash may be present.

SLE can be associated with polyarthritis but more usually causes polyarthralgia and tenosynovitis .

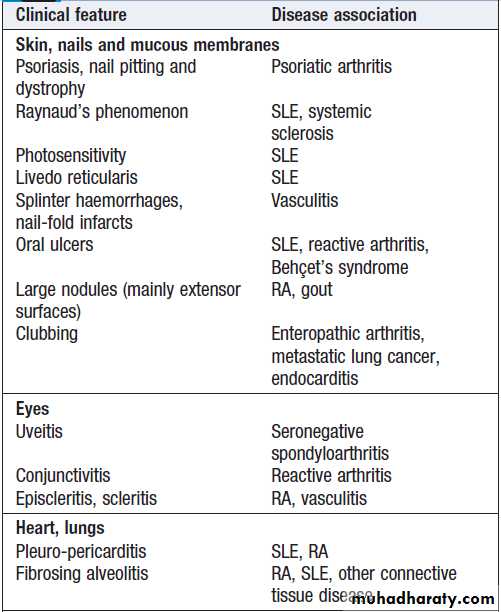

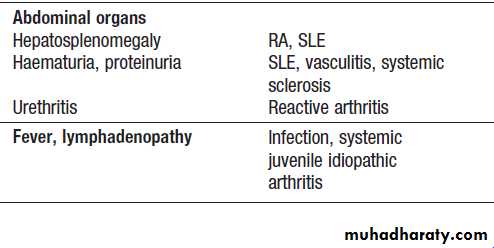

Extra-articular features of inflammatory arthritis

Fig. Patterns of joint involvement in different forms of polyarthritis.

A Rheumatoid arthritis typically targets the etacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and metatarsophalangeal joints of the feet, as well as other joints, in a symmetrical pattern.B Psoriatic arthritis targets proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the hands and larger joints in an asymmetrical pattern. Sacroiliitis (often asymmetrical) may occur.

C Ankylosing spondylitis targets the spine, sacroiliac joints and large peripheral joints in an asymmetrical pattern.

D Osteoarthritis targets the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the hands, first carpometacarpal joint at the base of the thumb, knees, hips, lumbar and cervical spine.

Investigations

Blood samples should be taken for routine haematology,

biochemistry, ESR, CRP, viral serology and an

immunological screen, including ANA, RF and ACPA.

Ultrasound examination or MRI may be required to

confirm the presence of synovitis if this is not obvious

clinically.

Management

should be directed at the underlying condition, but treatment with NSAIDs and analgesics may be required for symptom control until a diagnosis has been made.

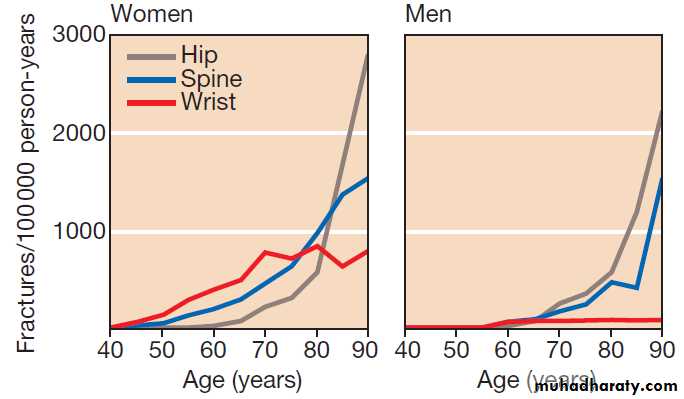

Fracture

Fractures are a common presenting symptom of osteoporosis, but they also occur in other bone diseases, in osteopenia and in some patients with normal bone.Clinical assessment

The presentation is with localised bone pain, which is worsened by movement of the affected limb or region.

There is usually a history of trauma but spontaneous fractures can occur in the absence of trauma in those with severe osteoporosis. The main differential diagnosis is soft tissue injury, but fracture should be suspected when there is marked pain and swelling, abnormal movement of the affected limb, crepitus or deformity. Femoral neck fractures typically produce a shortened, externally rotated leg that is painful to move.

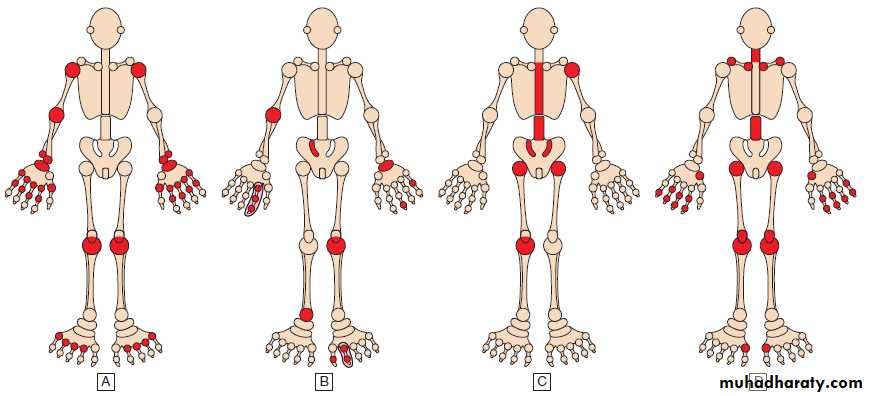

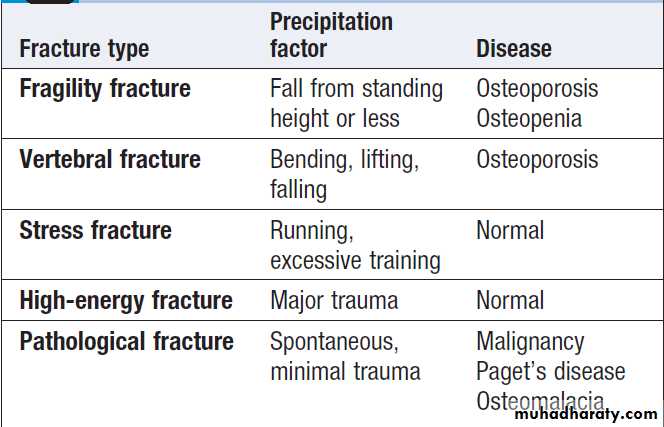

Characteristics of different fracture types

How to investigate a suspected fracture

Investigations

Radiographs of the affected site should be taken in atleast two planes and examined for discontinuity of the

cortical outline . In addition to demonstrating the fracture, X-rays may also show evidence of an underlying disorder, such as osteoporosis, Paget’s disease or osteomalacia. If the X-ray fails to show evidence of a

fracture but clinical suspicion remains high, MRI should

be performed, since this can demonstrate fractures that

are radiographically occult. Patients who are over the

age of 50 and present with fragility fractures should be

screened for the presence of osteoporosis by DEXA.

Management

Management of fracture in the acute stage requiresadequate pain relief, with opiates if necessary, reduction

of the fracture to restore normal anatomy, and immobilization of the affected limb to promote healing. This can be achieved either by the use of an external cast or splint or by internal fixation. Femoral neck fractures present a special management problem since non-union and avascular necrosis are common. This is especially true with intracapsular hip fractures, which should be treated by joint replacement surgery.

Following the fracture, rehabilitation is required with physiotherapy and a supervised exercise programme (this is especially important in older patients to prevent muscle-wasting and loss of mobility).

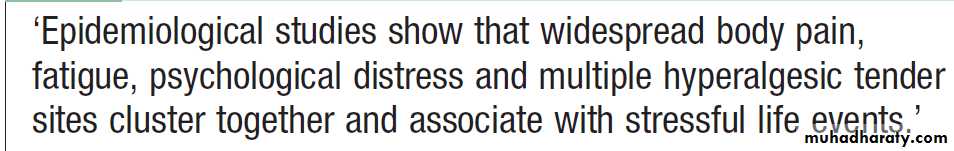

Generalised musculoskeletal pain

Clinical assessmentClinical history and examination can often indicate the underlying cause . Relentlessly progressive pain occurring in association with weight loss suggests malignant disease with bone metastases. Generalised bone pain may also occur in Paget’s disease if the disease is widespread, but Pagetic pain is usually more focal and

localised to the site of involvement . Widespread pain can occur in OA but this also tends to be localised to sites of involvement, such as the lumbar spine, hips, knees and hands. Signs of OA may be apparent on clinical examination. Osteomalacia can cause generalised bone pain that is associated with bone tenderness and limb girdle weakness.

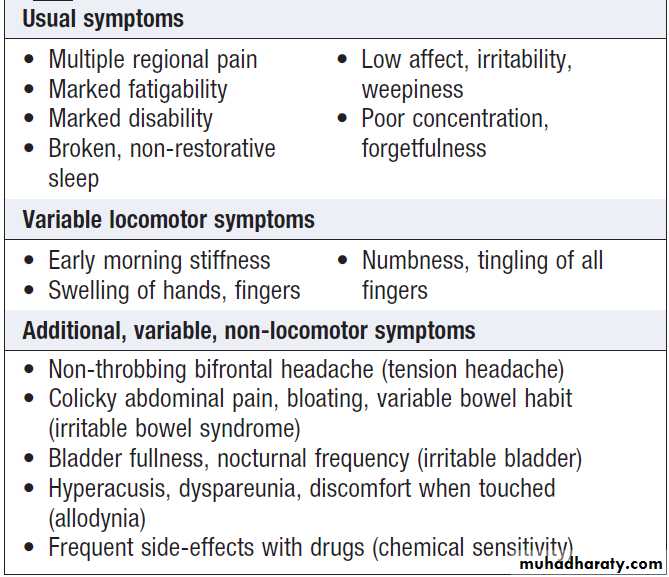

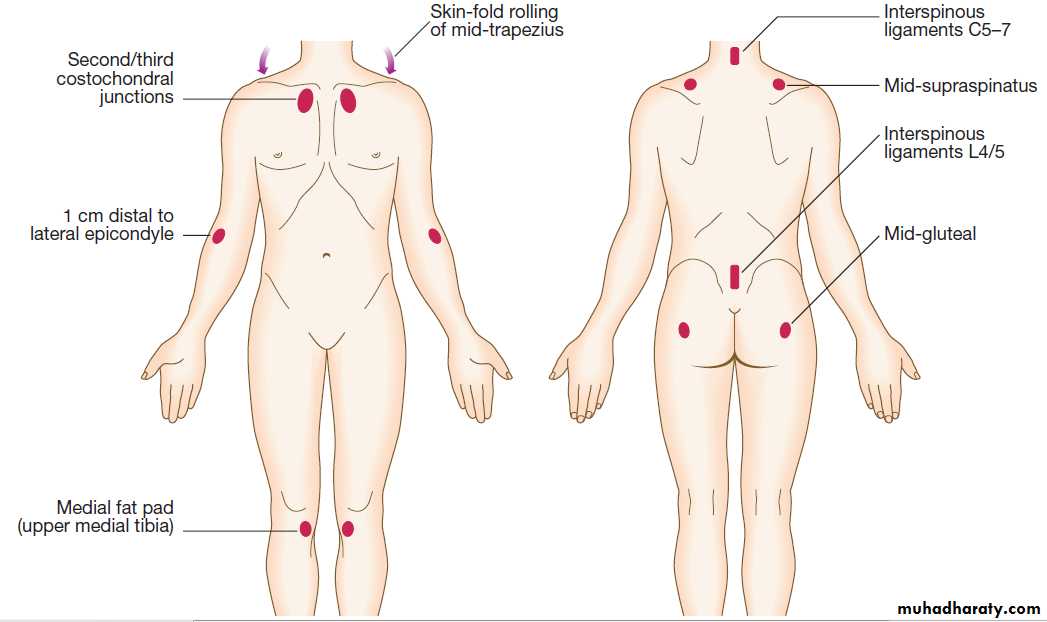

Fibromyalgia can present with generalised pain particularly affecting the trunk, back and neck. Accompanying features include fatigue, poor concentration and focal areas of hyperalgesia.

Causes of generalised pain

• Metastatic bone disease

• Fibromyalgia

• Joint hypermobility

• Osteomalacia

• Osteoarthritis

• Paget’s disease

• Polymyalgia rheumatica

• Myositis

Investigations

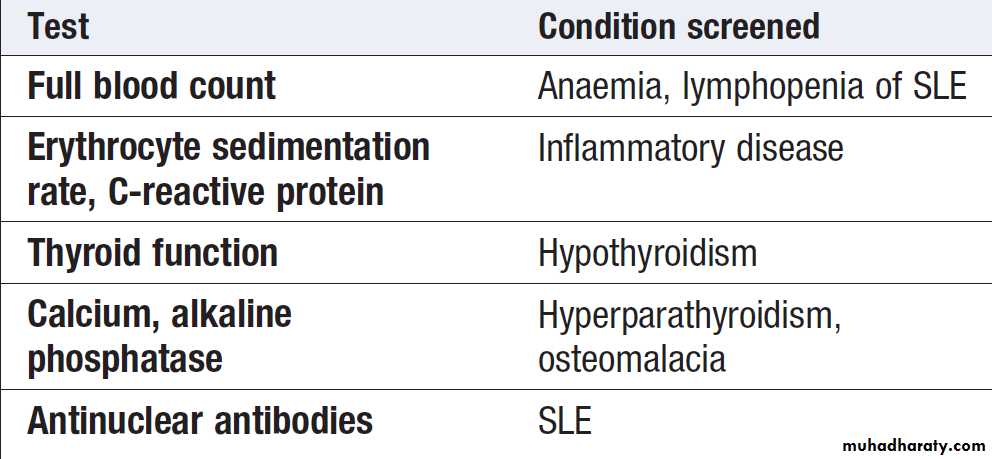

Radionuclide bone scanning is of value in patients suspected of having bone metastases and Paget’s disease. Myeloma should be excluded by plasma and urinary protein electrophoresis. If these results are positive, a radiological skeletal survey should be performed, since the isotope bone scan may be normal in myeloma.Routine biochemistry, vitamin D levels and PTH measurement should be performed if osteomalacia is suspected. In Paget’s disease, ALP may be elevated but can be normal in localised disease. Laboratory investigations are normal in patients with fibromyalgia and benign hypermobility.

Management

Management should be directed towards the underlyingcause. Chronic pain of unknown cause and that associated

with fibromyalgia responds poorly to analgesics

and NSAID, but may respond partially to antineuropathic

agents such as amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin

and pregabalin.

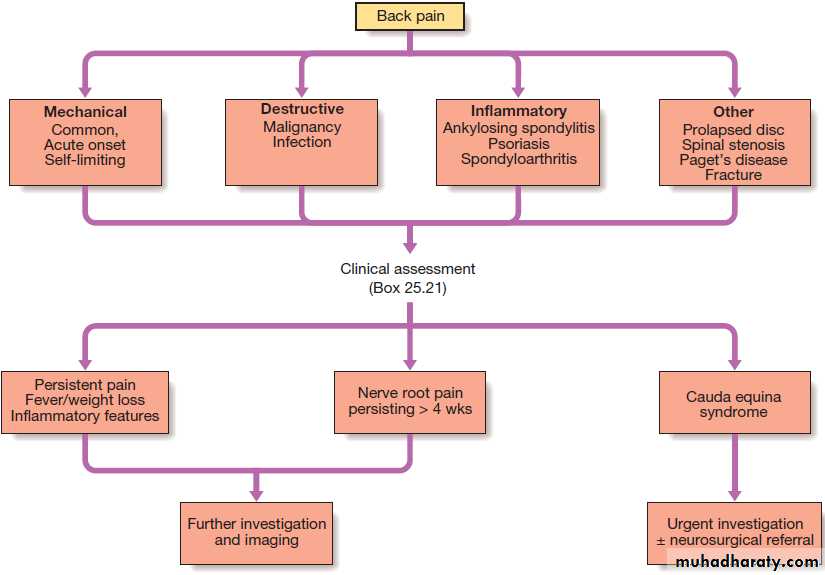

Back pain

A common symptom that affects 60–80% of people at some time in their lives.

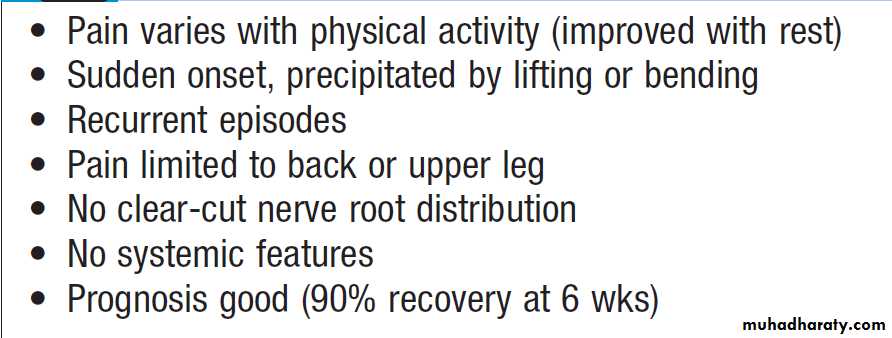

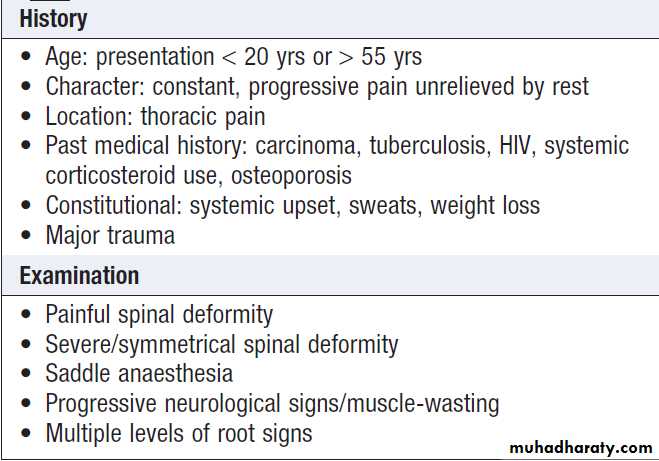

Clinical assessment

Mechanical back pain is the most common cause of acute back pain in people aged 20–55,accounts for > 90% of episodes, and is usually acute and associated with heavy lifting , twisting or bending. It is exacerbated by activity and is generally relieved by rest. Usually confined to the lumbar–sacral region, buttock or thigh, is asymmetrical, and does not radiate beyond the knee (which would imply nerve root irritation). On examination, there may be asymmetric local paraspinal muscle spasm and tenderness, and painful restriction of some movements.

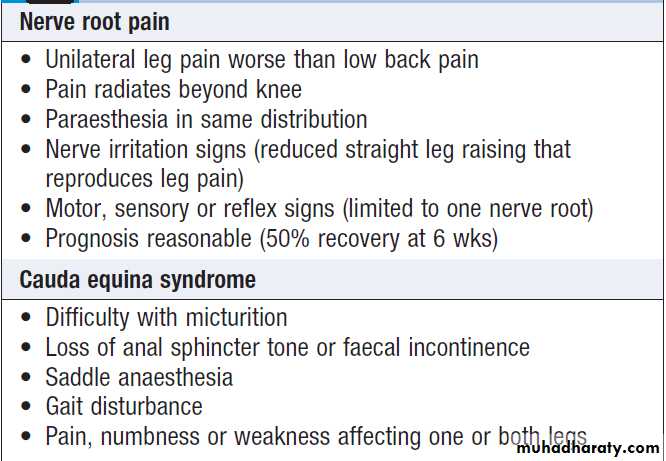

After 2 days, 30% are better and 90% have recovered by 6 weeks .Recurrences of pain may occur and about 10–15% go on to develop chronic back pain that may be difficult to treat. Psychological elements, such as job dissatisfaction, depression and anxiety, are important risk factors for the transition to chronic pain and disability. If there is clinical evidence of spinal cord or nerve root compression, or a cauda equina lesion , urgent investigation is needed.

Spinal stenosis presents with leg discomfort on walking that is relieved by rest (pseudoclaudication). Bending forwards or walking uphill may also relieve the pain.

Common causes include Paget, in which enlargement of the vertebrae may encroach on the spinal canal, and OA of the spine, in which osteophytes can have the same effect. Patients may adopt a characteristic simian posture, with a forward stoop and slight flexion at hips and knees.

Degenerative disc disease is a common cause of

chronic low back pain. Prolapse of an intervertebral

disc presents with nerve root pain, which can be accompanied by a sensory deficit, motor weakness, and asymmetrical reflexes. Examination may reveal a positive

sciatic or femoral stretch test. About 70% improve by 4 weeks. Inflammatory back pain due to seronegative spondyloarthritis has a gradual onset and almost always occurs before the age of 40.

It is associated with morning stiffness and improves with movement.

Spondylolisthesis may cause back pain that is typically aggravated by standing and walking. Occasionally,diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH )

can cause back pain but it is usually asymptomatic.

Arachnoiditis is a rare cause of chronic severe low

back pain.

It is due to chronic inflammation of the nerve root sheaths in the spinal canal and can complicate meningitis, spinal surgery, or myelography with oil-based contrast agents.

Causes of low back pain

• Mechanical back pain

• Prolapsed intervertebral disc

• Osteoarthritis

• Vertebral fracture

• Spinal stenosis

• Paget’s disease

• Spondylolysis

• Bone metastases

• Spondylolisthesis

• Arachnoiditis

• Scheuermann’s disease

Initial triage assessment of back pain.

Features of mechanical low back pain

Red flags for possible spinal pathology

Clinical features of radicular pain

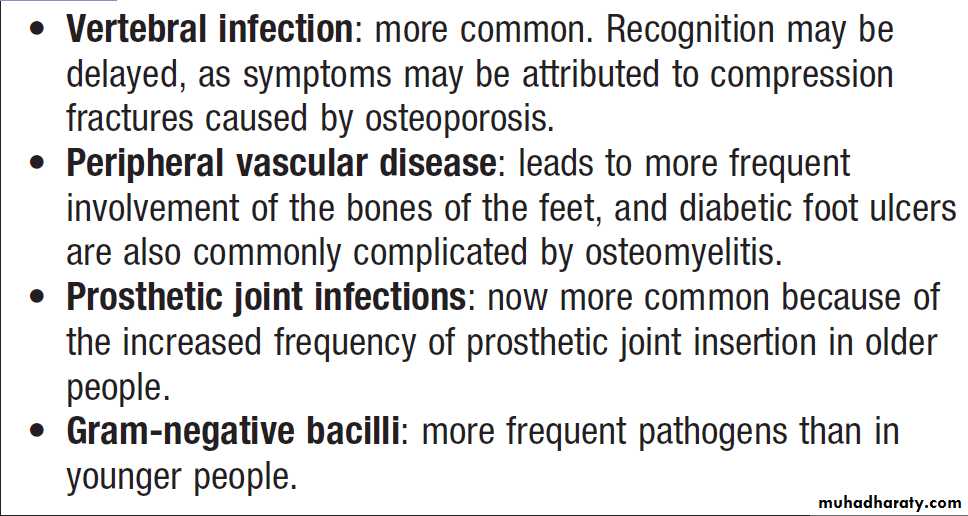

InvestigationsAre not required in acute mechanical back pain. Those with persistent pain (> 6 weeks) or red flags should undergo further investigation. MRI is the investigation of choice since it can demonstrate spinal stenosis, cord or nerve root compression, as well as inflammatory changes and infectious causes such as spinal abscess. Plain radiographs in suspected of having vertebral compression fractures, OA and degenerative disc disease. If metastatic disease is suspected, bone scan or SPECT should be considered. Additional investigations that may be required include ESR and CRP (to screen for sepsis and inflammatory disease), protein and urinary electrophoresis (for myeloma) and prostate specific antigen (for prostate carcinoma).

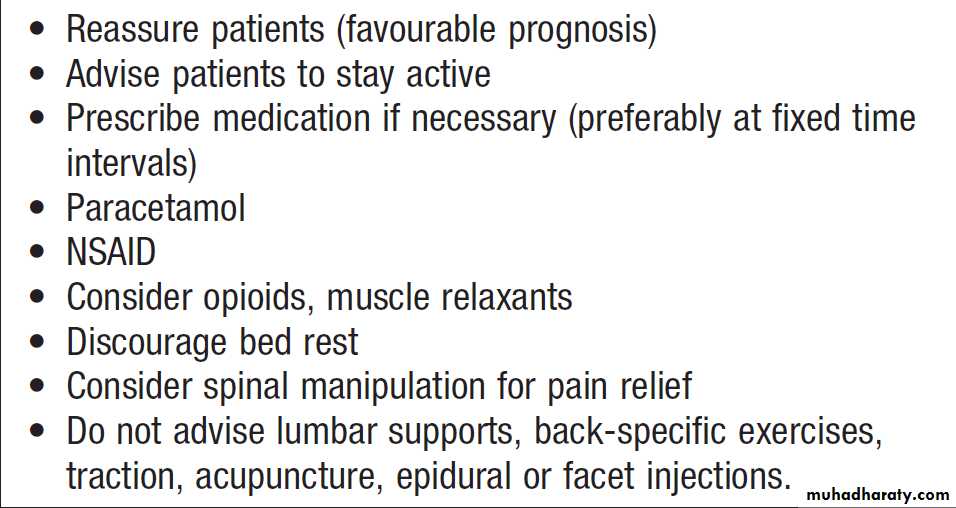

Management

Education is important in patients with mechanical backpain. It should emphasise the self-limiting nature of the

condition and the fact that exercise is helpful rather than

damaging. Regular analgesia and/or NSAIDs may be

required to improve mobility and facilitate exercise.

Return to work and normal activity should take place as

soon as possible. Bed rest is not helpful and may increase

the risk of chronic disability.

Referral for physiotherapy or manipulation should be considered if a return to normal activities has not been achieved by 6 weeks. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressant drugs may help pain, sleep and mood.

Other treatment modalities that are occasionally used

include epidural and facet joint injection, traction and

lumbar supports, though there is little evidence to

support their use. Malignant disease, osteoporosis,

Paget’s disease and spondyloarthropathies

require specific treatment of the underlying condition.

Surgery is required in less than 1% of patients with

low back pain but may be needed in spinal stenosis, in

spinal cord compression and in some patients with

nerve root compression.

Management of low back pain

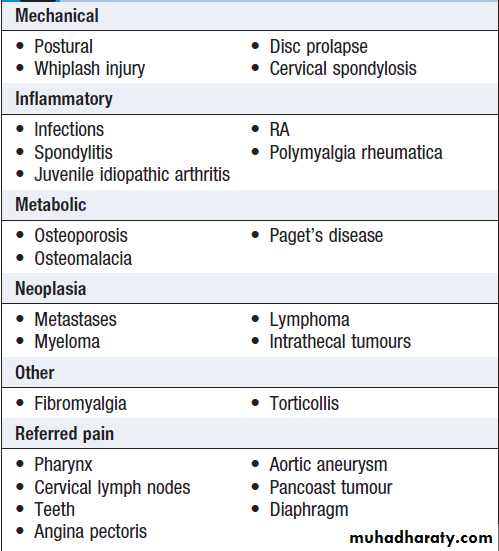

Neck painNeck pain is a common symptom that can occur following

injury (for example, whiplash), after falling asleep in

an awkward position, as a result of stress, or in association

with OA of the spine.

Most cases resolve spontaneously or with a short

course of NSAID or analgesics, and a soft collar. Patients

with persistent pain that follows a nerve root distribution

and those with neurological signs and symptoms

should be investigated by MRI scan, and if necessary

referred for a neurosurgical opinion.

Causes of neck pain

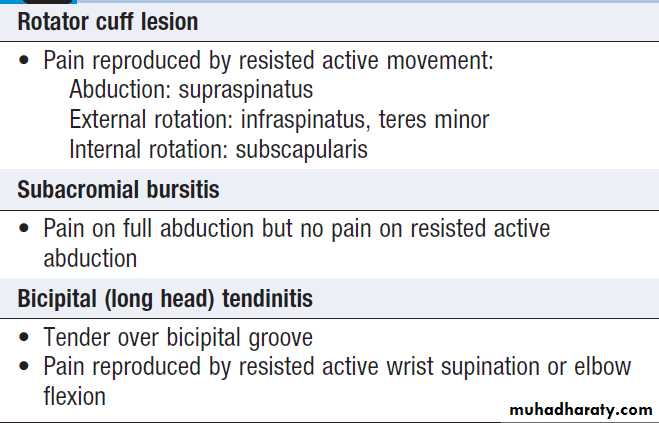

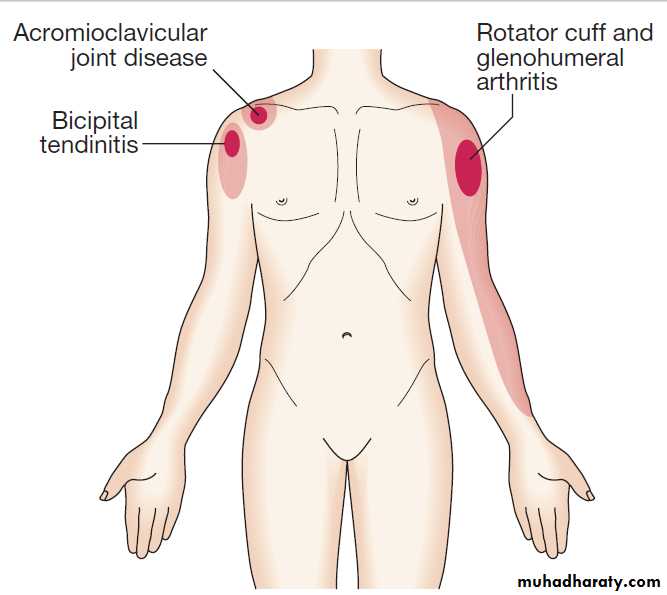

Shoulder painShoulder pain is a common complaint in both genders

> 40, and is most often due to degenerative disease of tendons in the rotator cuff .

Management is symptomatic, with analgesics, NSAID, local corticosteroid injections and physiotherapy aimed at restoring normal movement and function. Surgery may be required in debilitating symptoms in association with rotator cuff tears. Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) presents with upper arm pain that can progress over 4–10 weeks before subsiding over a similar time course. Restriction of glenohumeral movement is characteristic. In the early phase, there is marked anterior joint/ capsular tenderness and stress pain in a capsular pattern; later there is painless restriction, of movements.

Frozen shoulder is more common in diabetes mellitus,

but may also be triggered by a rotator cuff tear, localtrauma, myocardial infarction or hemiplegia.

Treatment in the early stage is with analgesia, intra- and extracapsular steroid injection, and regular ‘pendulum’ exercises of the arm to prevent the capsule from over-tightening.

Mobilising and strengthening exercises are the sole

treatment in the painless ‘frozen’ stage. The natural history is for slow but complete recovery, sometimes

taking up to 2 years.

Clinical findings in shoulder pain

Pain patterns around the shoulder. The dark shading indicates sites of maximum pain.

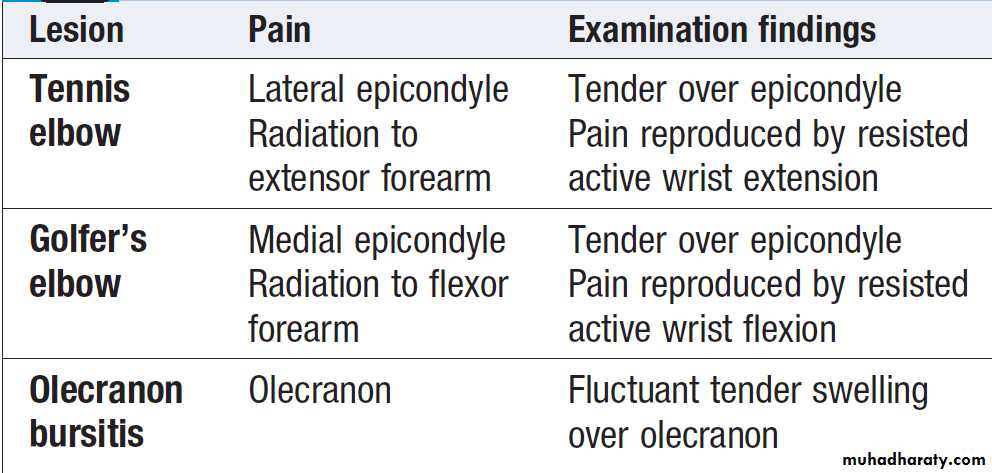

Elbow painThe most common causes are repetitive strain injury

affecting the lateral epicondyle (tennis elbow) and

medial epicondyle (golfer’s elbow) .

Management

is by rest, analgesics and topical or systemic

NSAID. Symptoms may also respond to local application

of glyceryl trinitrate patches. Local corticosteroid

injections may be required in resistant cases. Olecranon

bursitis can also follow local repetitive trauma but other

causes include infections, gout and RA.

Local causes of elbow pain

Hand and wrist pain

Pain from hand or wrist joints is well localised to the affected joint, except for pain from the first metacarpal joint, commonly targeted by OA; although maximal at the thumb base, the pain often radiates down the thumb and to the radial aspect of the wrist.Non-articular causes of hand pain include:

• Tenosynovitis: flexor or extensor (pain and swelling, with or without fine crepitus on volar or extensor aspect).

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis involves the tendon sheaths of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, and produces pain maximal over the radial aspect of the distal forearm and wrist. It usually occurs as the result of a repetitive strain injury.

There is tenderness (with or without warmth, linear swelling and fine crepitus) over the distal radius and marked pain on forced ulnar deviation of the wrist with the thumb held across the patient’s palm (Finkelstein’s sign).

• Raynaud’s phenomenon .

• C8/T1 radiculopathy.

• Reflex sympathetic dystrophy .

Hip pain

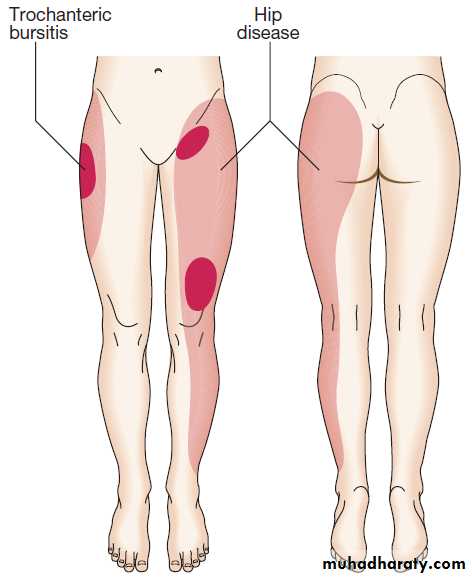

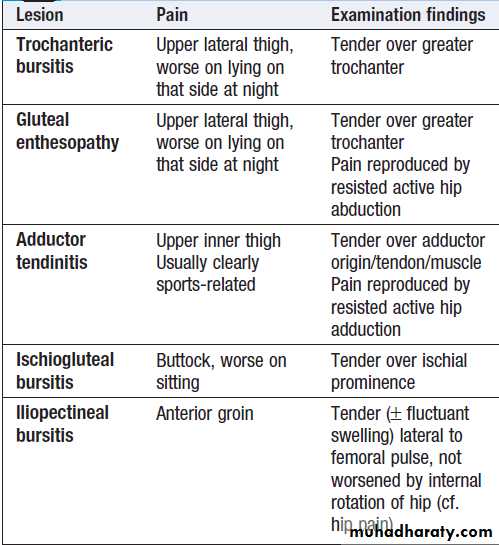

Pain from the hip joint is usually maximal deep in the anterior groin, with variable radiation to the buttock, anterolateral thigh, knee or shin . Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause , typically affecting obese women, and occurring in isolation or secondary to an abnormal gait, such as in hip or knee OA. Pain in the hip region may also be referred from the back. Root entrapment can cause pain in the lateral thigh (T12–L1) or the inguinal region and lateral thigh (L2–4), but is worsened by coughing and straining more than by movement and is often accompanied by sensory disturbance.Other less common causes include psoas abscess, retroperitoneal haemorrhage or pelvic inflammation, which can cause inguinal and lateral thigh pain that is aggravated by resisted hip flexion.

Pain patterns of hip disease and trochanteric bursitis.

The dark shading indicates sites of maximum pain.Local causes of hip pain

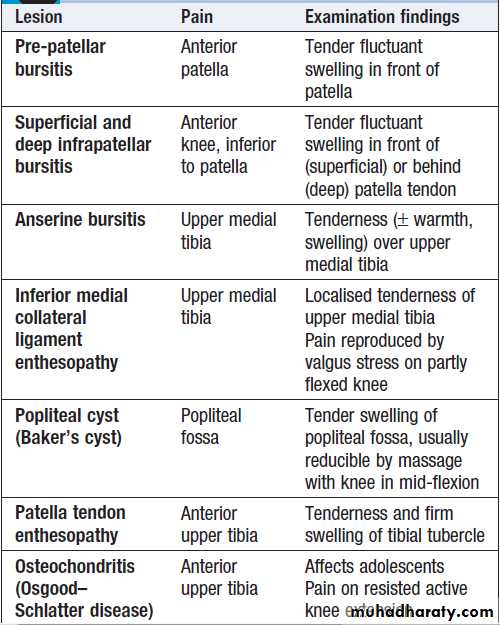

Knee painThe most common cause of knee pain is OA. Pain that is associated with locking of the knee (sudden painful inability to extend fully) is usually due to a meniscal tear or osteochondritis dissecans. Referred pain from the hip may present at the knee and is reproduced by hip not knee movement. Pain from periarticular lesions is well localised to the involved structure . Anterior knee pain may be due to bursitis occurring as the result of repetitive occupational kneeling, as well as infection and gout. Rarely, anterior knee pain may be the result of chondromalacia patellae, in which degenerative changes of the articular cartilage occur.

Local causes of knee pain

Ankle and foot painPain from the mortice joint of the ankle (the tibiofibular–

talar joint) is felt between the malleoli and is worse on

weight-bearing. Pain from the subtalar joint is also worse

on weight-bearing on uneven surfaces. The mortice joint

is commonly affected by OA, whereas RA tends to affect

the subtalar joint. Pain under the heel can arise from

plantar fasciitis or subcalcaneal bursitis. Pain affecting

the back of the heel may be due to Achilles tendinitis or

bursitis. Patients with seronegative spondyloarthritis

may develop enthesopathy affecting this region, resulting

in plantar fasciitis, which presents with pain and tenderness under the heel, or as Achilles enthesitis, which presents with pain at the tendon insertion into the calcaneus.

The MTP joints of the feet are commonly involved in RA. The presentation is with pain on walking below the metatarsal heads, often described as ‘walking

on marbles’. Patients with active inflammation of the

MTP joints have pain when the forefoot is squeezed .

Involvement of the first MTP joint is common in OA and is associated with a valgus deformity (hallux valgus). This joint is also a classical target in acute gout.

Claw foot (pes cavus) can be associated with anterior foot pain and is characterised by a high arch and clawing of the toes. It may be an isolated phenomenon or secondary to neurological disorders such as Friedreich’s ataxia

or spina bifida .

Management

Bursitis and enthesitis resistant to standard measures mayrespond to local steroid injections. Morton’s neuroma is

the name given to an entrapment neuropathy of the

interdigital nerves of the feet, which presents with shooting

pain that is usually located between the third and

fourth metatarsal heads. Women are most commonly

affected. Local sensory loss and a palpable tender swelling between the metatarsal heads may be detected. Footwear adjustment, with or without a local corticosteroid

injection, often helps but surgical decompression may be

required if symptoms persist.

Muscle pain and weakness

Muscle pain and weakness can arise from a variety ofcauses. It is important to distinguish between a subjective

feeling of generalised weakness or fatigue, and an

objective weakness with loss of muscle power and function.

Clinical assessment

Proximal muscle weakness suggests the presence of a

myopathy or myositis, which typically causes difficulty

with standing from a seated position, squatting and

lifting overhead. Worsening of symptoms on exercise and post-exertional cramps suggest a metabolic myopathy, such as glycogen storage disease . A strong family history and onset in childhood or early adulthood suggests muscular dystrophy .

Alcohol excess can cause an inflammatory myositis and atrophy of type 2 muscle fibres.

Proximal myopathy may be a complication of corticosteroid therapy and of osteomalacia. Myopathy and myositis can also occur in association with statin use and viral infections, including HIV infection, when it may be due to HIV itself or treatment with zidovudine.

Clinical examination should document the presence, pattern and severity of muscle weakness, and the latter should be assessed using the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale, in which muscle strength is graded on a six-point scale ranging from no power (0) to full power (5).

Investigations

Investigations should include routine biochemistry andhaematology. ESR and CRP, may be raised in inflammatory myositis and CK. Serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels and PTH should be checked in suspected osteomalacia. Raised CK levels suggest muscle pathology but do not establish the cause. Muscle biopsy and electromyography (EMG) are usually required to make the diagnosis, but MRI can be used to identify focal areas of muscle abnormality and increase the diagnostic yield from muscle biopsies.

Management

Management is determined by the cause but all patients

with muscle disease may benefit from physiotherapy

and graded exercises to maximise muscle function.

Inflammatory

• Polymyositis • Dermatomyositis • Inclusion body myositis • Polymyalgia rheumaticaEndocrine

• Hypothyroidism • Hyperthyroidism • Cushing’s syndrome • Addison’s disease

Metabolic

• Myophosphorylase deficiency • Phosphofructokinase deficiency • Hypokalaemia • Carnitine deficiency • Myoadenylate deaminase deficiency • Osteomalacia

Drugs/toxins

• Alcohol • Cocaine • Fibrates • Statins • Penicillamine • Zidovudine

Infections

• Viral (HIV, CMV, rubella, Epstein–Barr, echo) • Parasitic (schistosomiasis, cysticercosis, toxoplasmosis)

• Bacterial (Clostridium perfringens, staphylococci, TB , Mycoplasma)

Causes of proximal muscle pain or weakness

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Although management of musculoskeletal disease

depends on the underlying diagnosis, certain aspects of

management are common to many disorders. The

general aims of management are to:

• educate the patient

• control pain

• optimise function

• modify the disease process where this is possible

• identify and treat related comorbidity.

The management plan should be individualised and patient-centred, should involve all necessary members of the multidisciplinary team.

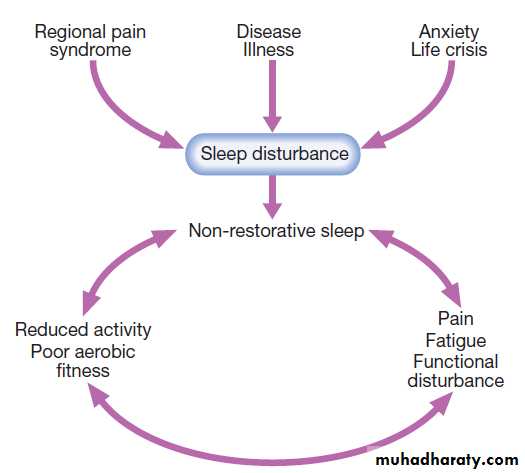

It must also take into account:

• the person’s daily activity requirements, and work

and recreational aspirations

• risk factors and associations of the musculoskeletal

condition (obesity, muscle weakness, nonrestorative sleep)

• the person’s perceptions and knowledge of the

condition

• medications and strategies already tried by the patient

• comorbid disease and its therapy

• the availability, costs and logistics of appropriate

evidence-based interventions.

Simple and safe interventions should be tried first.

Symptoms and signs will change with time, so the plan

requires regular review and re-adjustment. Effective

management may require the expertise of a variety of

health professionals, with a coordinated multidisciplinary

team approach.

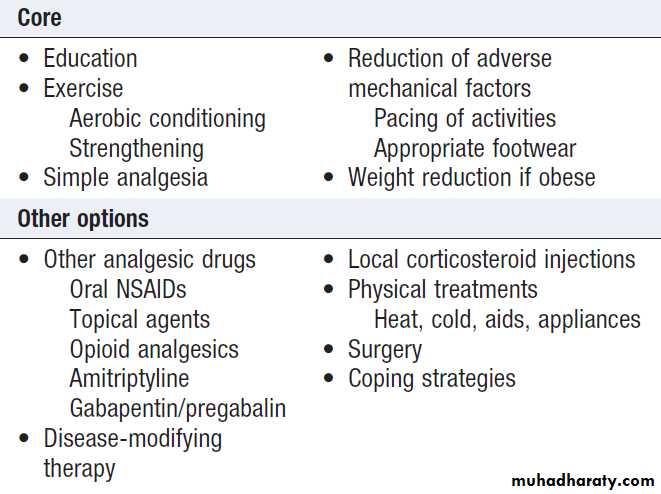

Core interventions that should be considered for

everyone with a painful musculoskeletal condition

are listed in Box .

There are also other nonpharmacological and drug options, the choice depending largely on the nature and severity of the diagnosis.

Core interventions for patients with

rheumatic diseasesEducation and lifestyle interventions

EducationPatients must always be informed about the nature of

their condition and its investigation, treatment and

prognosis, as education can improve outcome. Information

and therapist contact can reduce pain and disability,

improve self-efficacy and reduce the health-care costs . Education can be provided through one-to-one

discussion, written literature, patient-led group education

classes and interactive computer programs. Inclusion of the patient’s partner or carer is often appropriate.

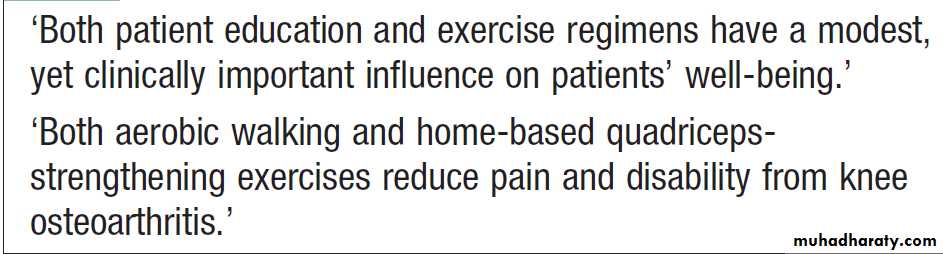

Exercise

• Aerobic fitness training can produce long-term reduction in pain and disability. It improves well-being, encourages restorative sleep and benefits common comorbidity such as obesity, diabetes, chronic heart failure and hypertension.

• Local strengthening exercise for muscles that act

over compromised joints also reduces pain and disability, with improvements in the reduced muscle strength, proprioception, coordination and balance that associate with chronic arthritis.

Education and exercise in the management of arthritis

Joint protectionExcessive impact-loading and adverse repetitive use of

a compromised joint or periarticular tissue can often be

reduced: for example, cessation of contact sports, or

altered use of machinery or tools at the workplace.

Simple ‘pacing’ of activities – dividing physically

onerous tasks into shorter segments with brief breaks in

between – is helpful. Use of shock-absorbing footwear

with thick soft soles can reduce impact-loading through

feet, knees, hips and back, and improve symptoms at

these sites. A walking stick held on the contralateral side

takes the weight off a painful hip, knee or foot.

Weight loss

Obesity aggravates pain at most sites of the body

through increased mechanical strain and is a risk factor

for more rapid progression of joint damage in patients

with arthritis. This should be explained to obese patients and strategies offered on how to lose and then maintain an appropriate weight .

Pharmacological treatment

Analgesics

Paracetamol (1 g up to 4 times daily) is the oral analgesic

of first choice and, if successful, the preferred long-term

oral analgesic. It inhibits prostaglandin synthesis in the

brain but has less effect on peripheral prostaglandin

production. It is generally well tolerated and has few

adverse effects and drug interactions.

There is a possible increased risk of both GI events and CVD with chronic usage, but it is uncertain whether this is due to the underlying disease or the drug itself.

If paracetamol fails, it can be used in combination with opioids such as codeine and dihydrocodeine in compound analgesic preparations like co-codamol (codeine and paracetamol) or co-dydramol (dihydrocodeine and paracetamol).

Although these are more effective than paracetamol, side-effects include constipation, headache and confusion, especially in the elderly. The centrally acting analgesics tramadol and meptazinol may be useful for temporary control of severe pain unresponsive to other measures. Both may cause nausea, bowel upset, dizziness and somnolence, and withdrawal symptoms after chronic use.

The non-opioid analgesic nefopam (30–90 mg 3 times daily) can help moderate pain, though side-effects (nausea, anxiety, dry mouth) often limit its use. Patients with severe or intractable pain may require stronger opioid analgesics such as oxycodone and morphine.

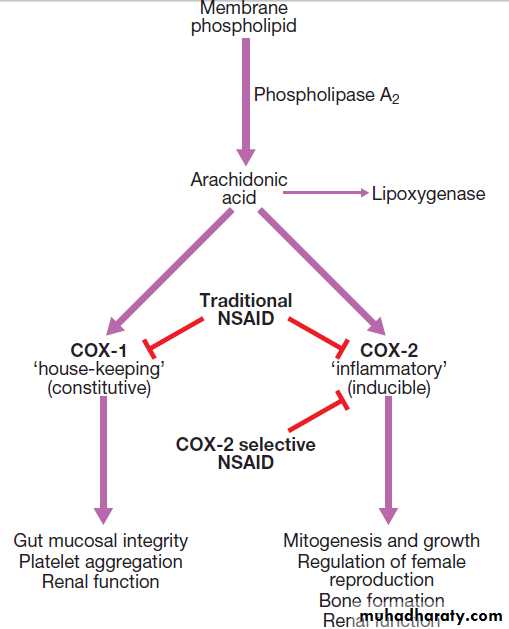

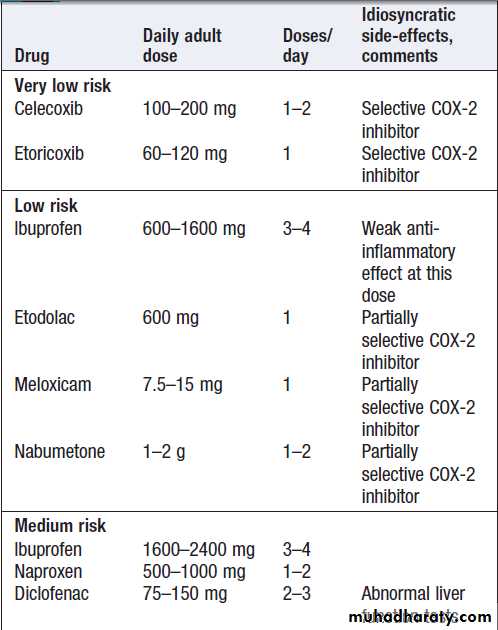

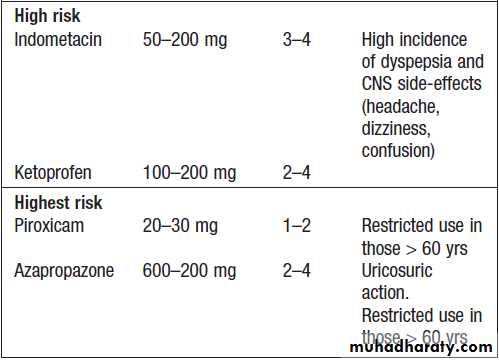

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

These are among the most widely prescribed drugs, but their use has declined over recent years because of concerns about an increased risk of CVD. Oral NSAIDs are particularly useful in the management of pain that has an inflammatory component, and a long-acting NSAID taken in the evening may help reduce early morning stiffness. There is marked variability in individual tolerance and response; patients who do not respond to one NSAID may still gain relief from another. The mechanism of action is through inhibition of prostaglandin H synthase and cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes.

Arachidonic acid,derived from membrane phospholipids, is metabolized to produce prostaglandins and leukotrienes by the COX and 5-lipoxygenase pathways respectively .

There are two isoforms of COX, encoded by different

genes. COX-1 is expressed and fulfils a ‘housekeeping’ function in the gastric mucosa, platelets and kidneys. The COX-2 enzyme is largely induced at sites of inflammation, producing prostaglandins that cause local pain and inflammation, but COX-2 is also up-regulated in the CNS, where it plays a role in the central mediation of pain and fever. Traditional NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen, inhibit both COX enzymes, whereas newer celecoxib and etoricoxib, selectively inhibit COX-2.

Whilst NSAIDs have anti-inflammatory activity,

they are not thought to have a disease-modifying effectin either OA or inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

Non-selective NSAIDs can damage the gastric and

duodenal mucosal barrier and are associated with

an increased risk of upper GI ulceration, bleeding and perforation.

Dyspepsia is a poor guide to the presence of NSAID-associated ulceration and bleeding .

Co-prescription of omeprazole (20 mg daily) or misoprostol (200 μg twice or 3 times daily) reduces but does not eliminate NSAID-induced ulceration and bleeding, but H2-antagonists in standard doses are ineffective.

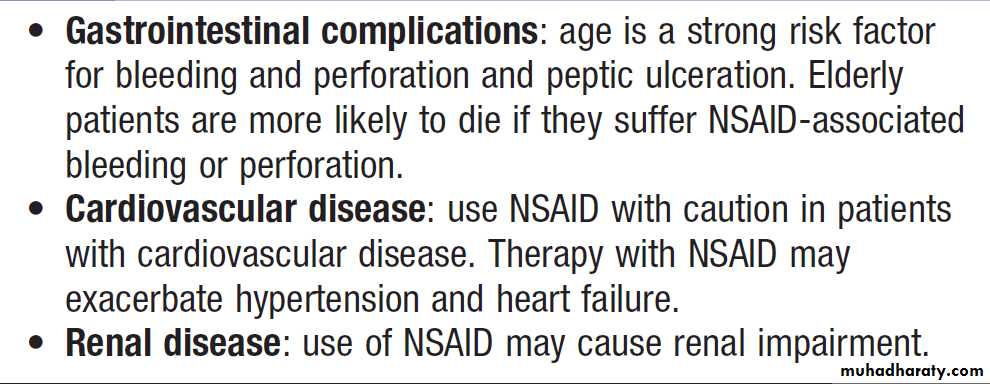

The selective COX-2 inhibiter are much less likely to cause gastrointestinal toxicity but benefit is attenuated in patients on low dose aspirin. In the UK, NICE guidelines advise that PPI should be co-prescribed with all NSAIDs, including COX-2 selective NSAIDs, even though the risk of GI events with these is low. Since chronic PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of hip fracture, the merits of giving PPI therapy with a COX-2 selective drug need to be weighed up carefully. Other SE include fluid retention and renal impairment due to inhibition of renal prostaglandin production, non-ulcer-associated dyspepsia, abdominal pain and altered bowel habit, and rashes. Interstitial nephritis, asthma and anaphylaxis can also occur but are rare. Because of the risk of adverse effects, NSAIDs should be used with great care in the elderly .

COX-1 and COX-2 pathways.

Commonly used NSAIDs and their relative

risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and perforationRisk factors for NSAID-induced ulcers

• Age > 60 yrs*• Past history of peptic ulcer*

• Past history of adverse event with NSAID

• Concomitant corticosteroid use

• High-dose or multiple NSAID

• High-risk NSAID

*The most important risk factors.

Use of oral NSAID in old age

Recommendations for the use of NSAID• Use with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease

• Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible to control symptoms

• Avoid NSAID in patients on warfarin

• Allow 2–3 weeks to assess efficacy. If response is

inadequate, consider trial of another NSAID

• Never prescribe more than one NSAID at a time

• Co-prescribe proton pump inhibitor for patients with risk

factors for gastrointestinal adverse effects

Topical agents

Topical NSAID creams and gels and capsaicin cream can help in the treatment of OA and superficial periarticular lesions affecting hands, elbows and knees. They may be used as monotherapy or as an adjunct to oral analgesics. Topical NSAIDs can penetrate superficial tissues and even reach the joint capsule. Initial application causes a burning sensation but continued use depletes presynaptic substance P, with subsequent pain reduction that is optimal after 1–2 weeks.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Physical and occupational therapyLocal heat, ice packs, wax baths and other local external

applications can induce muscle relaxation and temporary

relief of symptoms in a range of rheumatic diseases.

Hydrotherapy induces muscle relaxation and facilitates

Enhanced movement in a warm, pain-relieving

environment without the restraints of gravity and

normal load-bearing. Various manipulative techniques

may also help improve restricted movement. Splints can give temporary rest and support for painful joints and periarticular tissues, and prevent harmful involuntary postures during sleep.

Prolonged rest, however, must be avoided.

Orthoses are more permanent appliances used to

reduce instability and excessive abnormal movement.They include working wrist splints, knee orthoses, and

iron and T-straps to control ankle instability. Aids and appliances can provide dignity and independence to patients with respect to activities of daily living. Common examples are a raised toilet seat, raised chair height, extended handles on taps, a shower instead of a bath, thick-handled cutlery, and extended ‘hands’ to pull on tights and socks. Full assessment and advice from an occupational therapist maximise the benefits of these.

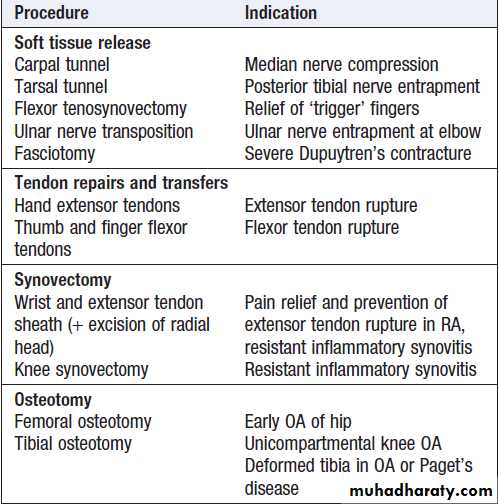

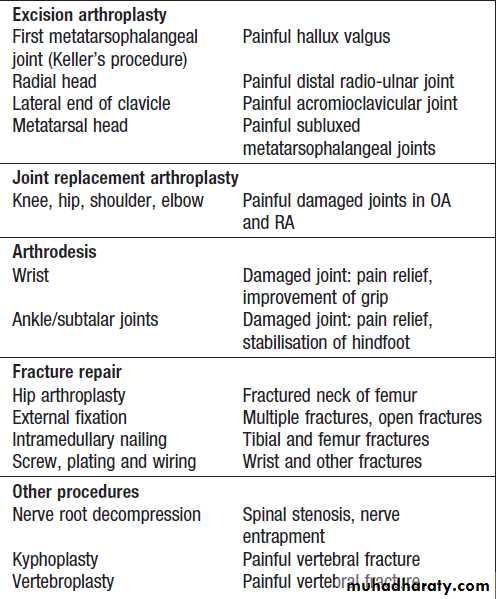

Surgery

A variety of surgical interventions can relieve pain and conserve or restore function in patients with bone, joint and periarticular disease .Soft tissue release ,tenosynovectomy may reduce inflammatory symptoms, improve function.Synovectomy of joints does not prevent disease progression but may be indicated for pain relief when drugs, physical therapy and intra-articular injections have provided insufficient relief. The main approaches for damaged joints are osteotomy (cutting bone to alter joint mechanics and load transmission), excision arthroplasty (removing part or all of the joint), joint replacement and arthrodesis (joint fusion). Surgical fixation of fractures.Surgical procedures in rheumatology and

bone diseaseSelf-help and coping strategies

These help patients to cope better with, and adjust to,chronic pain and disability. They may be useful at any stage but are particularly so for patients with incurable

problems, who have tried all available treatment options.

The aim is to increase self-management through self-assessment and problem-solving, so that patients can

recognise negative but potentially remediable aspects of

their mood (stress, frustration, anger or low self-esteem)

and their situation (physical, social, financial). Involvement of the spouse or partner in mutual goal setting can improve partnership adjustment. Such approaches are often an element of group education and pain clinics, but may require more formal clinical psychological input.

Self-help and coping strategies

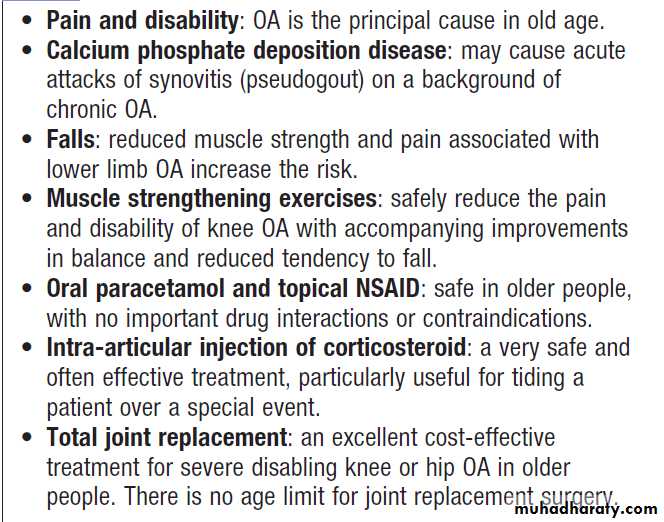

OSTEOARTHRITIS (OA)

OA is by far the most common form of arthritis. It is strongly associated with ageing and is a major cause of pain and disability in older people. Osteoarthritis is characterised by focal loss of articular cartilage, subchondral osteosclerosis, osteophyte formation at the joint margin, and remodelling of joint contour with enlargement of affected joints. Inflammation can occur but is not a prominent feature.Joint involvement in OA follows a characteristic distribution, mainly targeting the hips, knees, PIP and DIP joints of the hands, neck and lumbar spine .

The prevalence of OA rises progressively with age. Symptoms attributable to OA are more prevalent in women, except at the hip, men are equally affected.

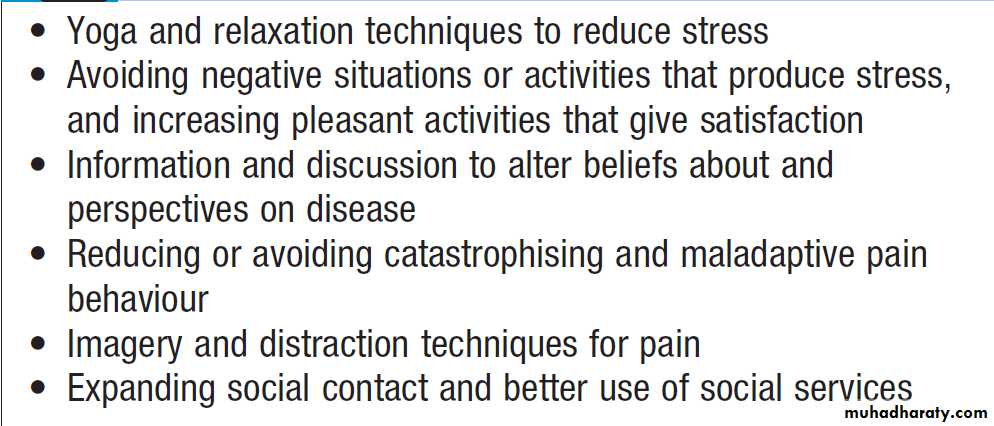

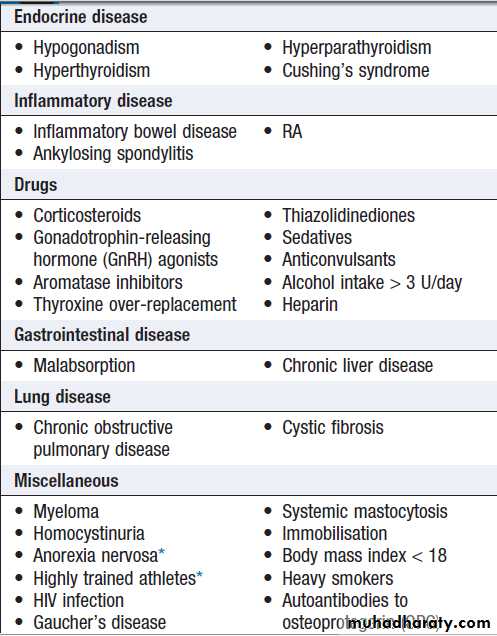

Pathophysiology

OA is a complex disorder with both genetic and environmental components . Repetitive adverse loading of joints during occupation or competitive sports is also an important predisposing factor in farmers (hip OA), miners (knee OA) and elite or professional athletes (knee OA). Congenital abnormalities, such as slipped femoral epiphysis, are also associated with a high risk, and this is also thought to be the explanation for the increased risk of OA in Paget’s disease of bone.

Obesity is another strong risk factor. Although this

is likely to be due in part to increased mechanical loadingof the joints, it has been speculated that cytokines

released from adipose tissue may also play a role. The

increased incidence of OA in women has led to speculation

that sex hormones may play a causal role.

Some studies have shown a lower prevalence of OA in women who use hormone replacement therapy (HRT), as compared with non-users.

Genetic factors play a key role in the pathogenesis of OA, and family-based studies have estimated that the heritability of OA ranges between about 43% at the knee to between 60% and 65% at the hip and hand, respectively.

Risk factors for the development of osteoarthritis.

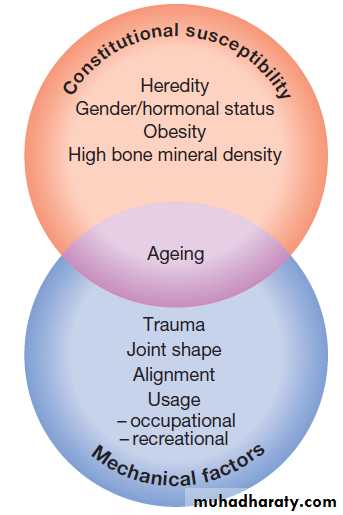

Pathological changes in osteoarthritis.

A Abnormalnests of proliferating chondrocytes (arrows) interspersed with matrix devoid

of normal chondrocytes.

B Fibrillation of cartilage in OA.

C Radiograph

of knee joint affected by OA, showing osteophytes at joint margin (white arrows), subchondral sclerosis (black arrows) and subchondral cyst (open arrow).

Clinical features

The main presenting symptoms are pain and functionalrestriction in a patient over the age of 45, but more

often over 60 years. The causes of pain in OA are not

completely understood but may relate to increased

pressure in subchondral bone (mainly causing night

pain), trabecular microfractures, capsular distension and

low-grade synovitis, or may result from bursitis and

enthesopathy secondary to altered joint mechanics.

Radiological evidence of OA is very common in

middle-aged and older people, and may coexist with other conditions, so it is important to remember that pain in a patient with OA may be due to another cause.

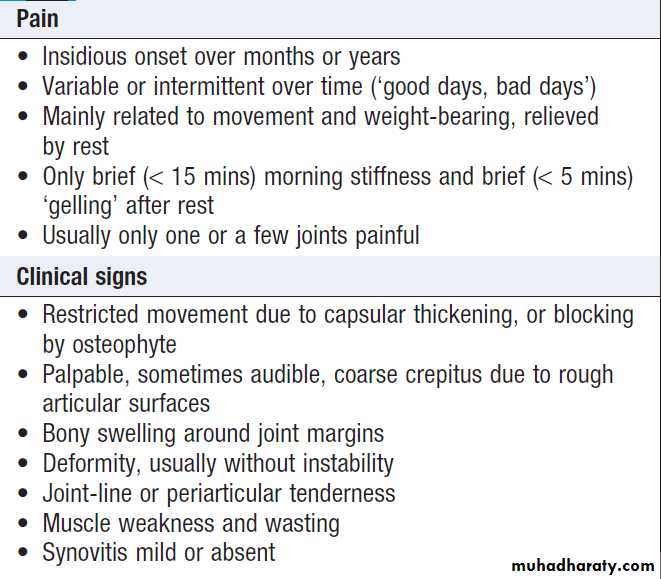

Symptoms and signs of osteoarthritis

Generalised nodal OASome patients are asymptomatic whereas others develop pain, stiffness and swelling of one or more PIP joints of the hands from the age of about 40 years onward. Gradually, these develop posterolateral swellings on each side of the extensor tendon that slowly enlarge and harden to become Heberden’s (DIP) and Bouchard’s (PIP) nodes. Typically, each joint goes through a phase of episodic symptoms (1–5 years) while the node evolves and OA develops. Once OA is fully established, symptoms may subside and hand function often remains good. Affected joints are enlarged as the result of osteophyte formation and often show characteristic lateral deviation, reflecting the asymmetric focal cartilage loss of OA .

Clinically, it may be detected by the presence of crepitus on joint movement, and squaring of the thumb base.

Generalised nodal OA has a very strong genetic component: the daughter of an affected mother has a 1 in 3 chance of developing nodal OA herself. People with

nodal OA are at increased risk of OA at other sites,

especially the knee.

Characteristics of generalised nodal OA

Nodal osteoarthritis. Heberden’s nodes and lateral (radial/ ulnar) deviation of distal interphalangeal joints, with mild Bouchard’s nodes at the proximal IP joints.

X-ray appearances in hand osteoarthritis. There is

marked loss of joint space at all of the distal interphalangeal joints, with osteophyte formation most marked at the first and second DIP joints. The

fifth proximal interphalangeal joint also shows loss of joint space with osteophyte formation.

Knee OA

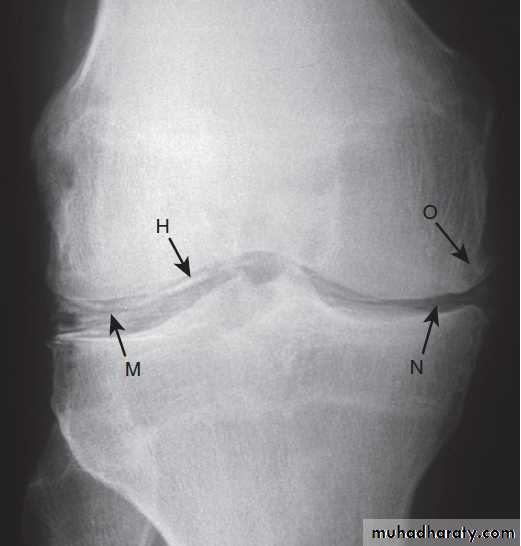

OA principally targets the patello-femoral and medialtibio-femoral compartments at this site but eventually

spreads to affect the whole of the joint (Fig.). It may

be isolated or occur as part of generalised nodal OA.

Most patients, particularly women, have bilateral and

symmetrical involvement. With men, trauma is a more

important risk factor and may result in unilateral OA.

The pain is usually localised to the anterior or medial

aspect of the knee and upper tibia. Patello-femoral pain

is usually worse going up and down stairs or inclines.

Posterior knee pain suggests the presence of a complicating popliteal cyst (Baker’s cyst). Prolonged walking, rising from a chair, getting in or out of a car, or bending to put on shoes and socks may be difficult. Local examination findings may include:

• a jerky, asymmetric (antalgic) gait with less time

weight-bearing on the painful side

• a varus less commonly valgus, and/or fixed flexion deformity

• joint-line and/or periarticular tenderness

(secondary anserine bursitis and medial ligament

enthesopathy causing tenderness of the upper medial tibia)

• weakness and wasting of the quadriceps muscle

• restricted flexion/extension with coarse crepitus

• bony swelling around the joint line.

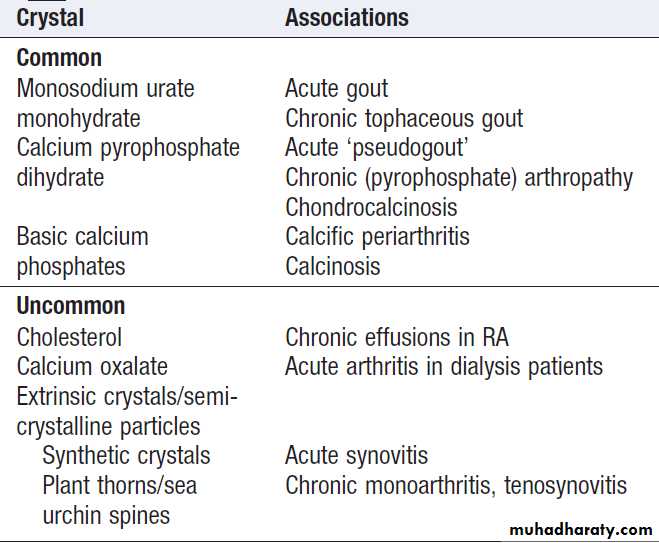

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystal

deposition in association with OA is most common

at the knee.

This may result in a more overt inflammatory component (stiffness, effusions) and super-added acute attacks of synovitis (‘pseudogout’), which may predict more rapid radiographic and clinical progression.

X-ray appearances in knee osteoarthritis. There is almost complete loss of joint space affecting both compartments,

And sclerosis of subchondral bone.

Typical varus deformity resulting from marked medial

tibio-femoral osteoarthritis.Hip OA

Hip OA most commonly targets the superior aspect ofthe joint . This is often unilateral at presentation,

frequently progresses with superolateral migration

of the femoral head, and has a poor prognosis. The less

common central (medial) OA shows more central cartilage

loss and is largely confined to women.

It is often bilateral at presentation and may associate with generalised nodal OA.

It has a better prognosis than superior hip OA and progression to axial migration of the femoral

head is uncommon.

The hip shows the best correlation between symptoms

and radiographic change. Hip pain is usually

maximal deep in the anterior groin, with variable radiation to the buttock, anterolateral thigh, knee or shin.

Lateral hip pain, worse on lying on that side with tenderness over the greater trochanter, suggests secondary trochanteric bursitis.

Common functional difficulties are the same as for knee OA; in addition, restricted hip abduction in women may cause pain on intercourse.

Examination may reveal:

• an antalgic gait• weakness and wasting of quadriceps and gluteal muscle

• pain and restriction of internal rotation with the hip

flexed – the earliest and most sensitive sign of hip

OA; other movements may subsequently be restricted and painful

• anterior groin tenderness just lateral to the femoral

pulse

• fixed flexion, external rotation deformity of the hip

• ipsilateral leg shortening with severe joint attrition

and superior femoral migration.

Although obesity is not a major risk factor for development

of hip OA, it is associated with more rapid progression.

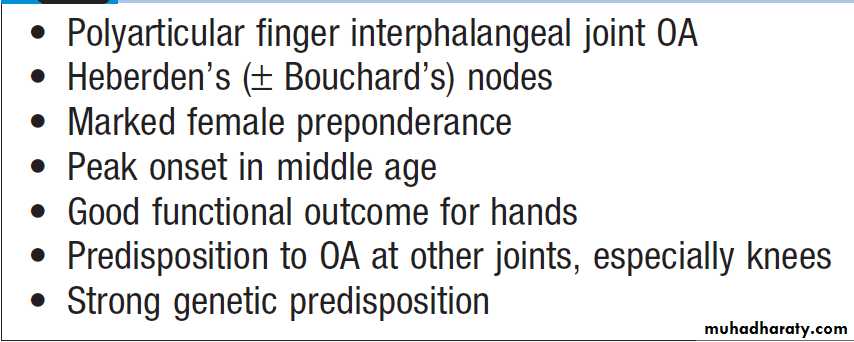

X-ray of hip showing changes of osteoarthritis. Note

the superior joint space narrowing (N), subchondral sclerosis (S), marginalosteophytes (white arrows) and cysts (C).

Spine OA

The cervical and lumbar spine are predominantly targeted, then referred to as cervical spondylosis and lumbar spondylosis, respectively . Spine OA may occur in isolation or as part of generalised OA. The typical presentation is with pain localised to the low back region or the neck, although radiation of pain to the arms, buttocks and legs may also occur due to nerve root compression. The pain is typically relieved by restand worse on movement. On physical examination, the

range of movement may be limited and loss of lumbar

lordosis is typical. The straight leg-raising test or femoral

stretch test may be positive and neurological signs may

be seen in the legs where there is complicating spinal

stenosis or nerve root compression.

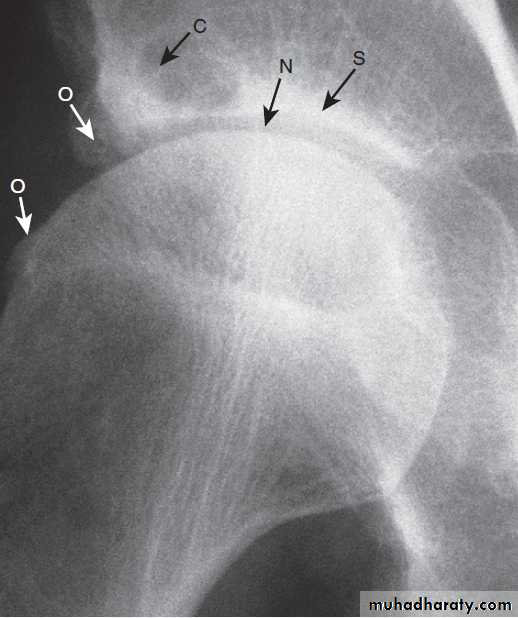

X-ray of spine showing typical changes of

osteoarthritis. Cervical spondylosis showing disc space narrowingbetween C6 and C7, osteophytes at the anterior vertebral body margins (arrows) and osteosclerosis at the apophyseal joints.

Early-onset OA

Unusually, typical symptoms and signs of OA may

present before the age of 45. In most cases, a single joint

is affected and there is a clear history of previous trauma.

However, specific causes of OA need to be considered

in people with early-onset disease affecting several

joints, especially those not normally targeted by OA,

rare causes need to be considered . Kashin–

Beck disease is a rare form of OA that occurs in children,

typically between the ages of 7 and 13, in some regions of China. The cause is unknown but suggested predisposing

factors are selenium deficiency and contamination

of cereals with mycotoxin-producing fungi.

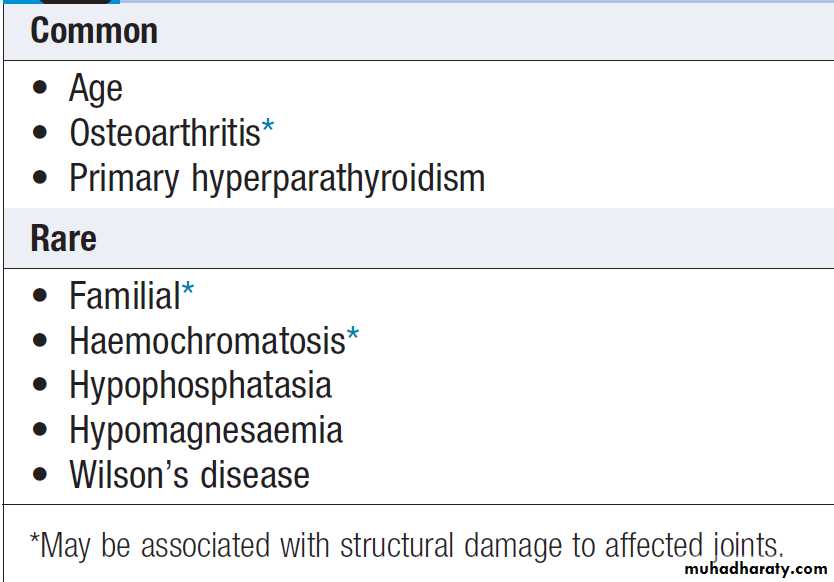

Causes of early-onset osteoarthritis

Monoarticular• Previous trauma, localised instability

Pauciarticular or polyarticular

• Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

• Metabolic or endocrine disease Haemochromatosis ,

Ochronosis , Acromegaly

• Spondylo-epiphyseal dysplasia

• Late avascular necrosis

• Neuropathic joint

• Kashin–Beck disease

Erosive OA

This term is used to describe rare patients with hand OA

who have a more prolonged symptom phase, more overt

inflammation, more disability and worse outcome than

those with nodal OA. Distinguishing features include

preferential targeting of PIP joints, subchondral erosions

on X-rays, occasional ankylosis of affected joints and

lack of association with OA elsewhere.

It is unclear whether erosive OA is part of the spectrum of hand OA or a discrete subset.

Investigations

A plain X-ray will show one or more of the typical featuresof OA . In addition to providing diagnostic information, X-rays are used to assess the severity of structural change, which is useful if joint replacement surgery is being considered. Non-weight-bearing postero-anterior views of the pelvis are adequate for assessing hip OA. Patients with suspected knee OA should have standing antero-posterior radiographs taken to assess tibio-femoral cartilage loss, and a flexed skyline view to assess patello-femoral involvement. Spine OA can often be diagnosed on plain X-ray, which typically shows evidence of disc space narrowing

and osteophytes. If nerve root compression or spinal

stenosis is suspected, MRI should be performed.

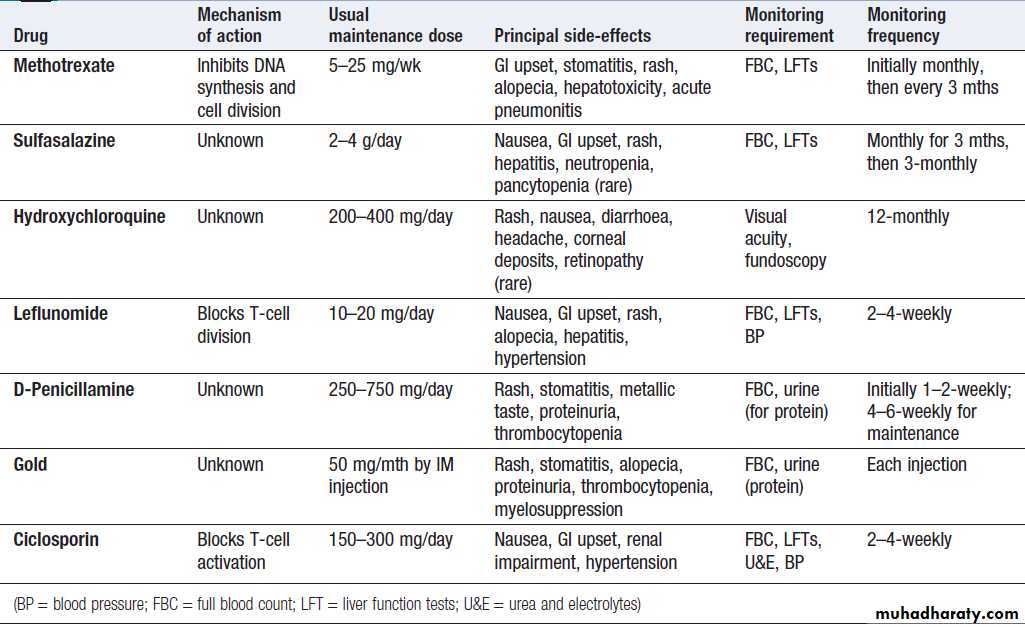

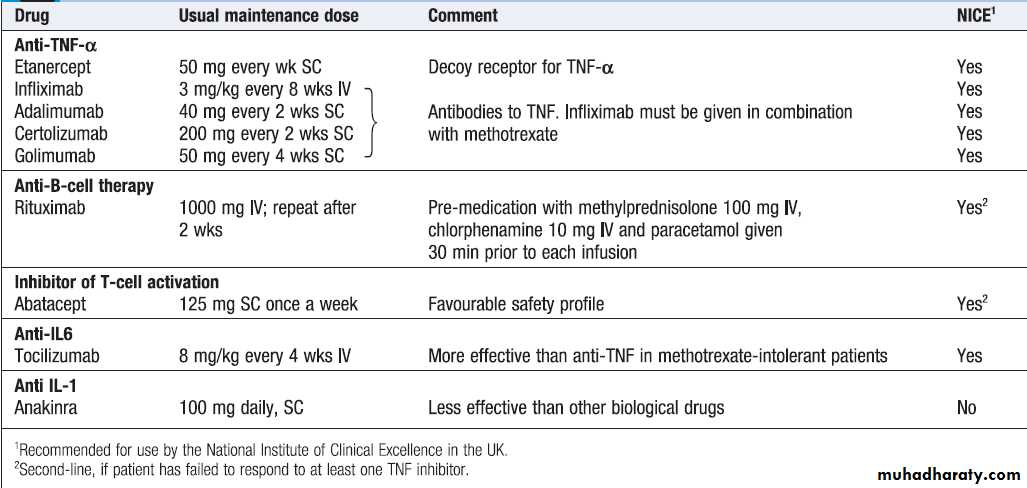

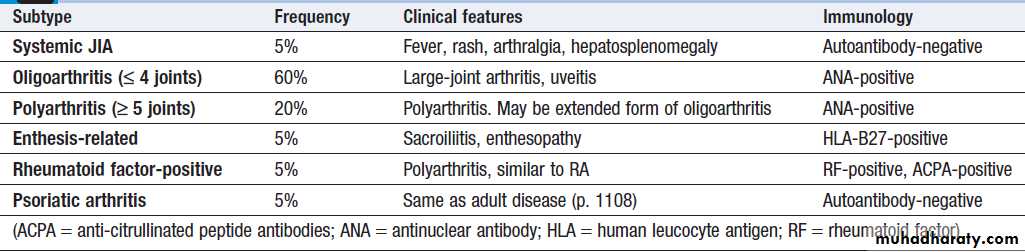

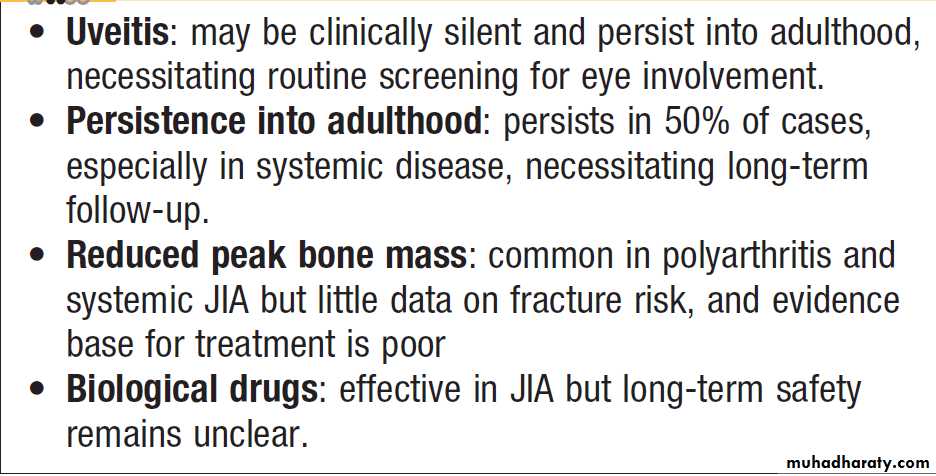

Routine biochemistry, haematology and autoantibody