Bronchial Carcinoma

Part 1Cigarette smoking is by far the most important cause of lung cancer. It is thought to be directly responsible for at least 90% of lung carcinomas, the risk being proportional to the amount smoked and to the tar content of cigarettes.

The death rate from the disease in heavy smokers is 40 times that in non-smokers.

Risk falls slowly after smoking cessation, but remains above that in non-smokers for many years.It is estimated that 1 in 2 smokers dies from a smoking-related disease, about half in middle age.

The effect of ‘passive’ smoking is thought to be a factor in 5% of all lung cancer deaths.

Exposure to naturally occurring radon is another risk.

The incidence of lung cancer is slightly higher in urban than in rural dwellers, which may reflect differences in atmospheric pollution (including tobacco smoke) or occupation.

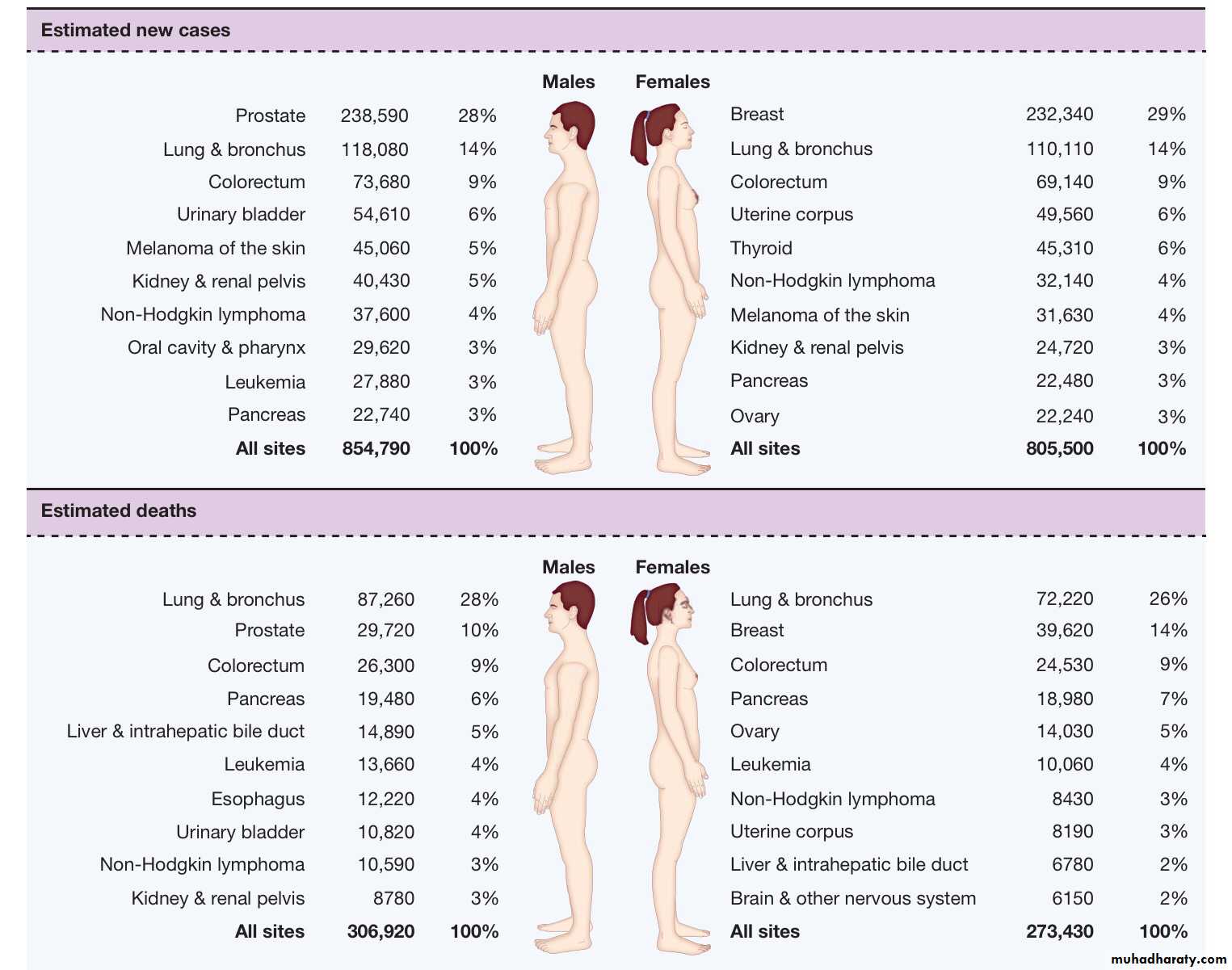

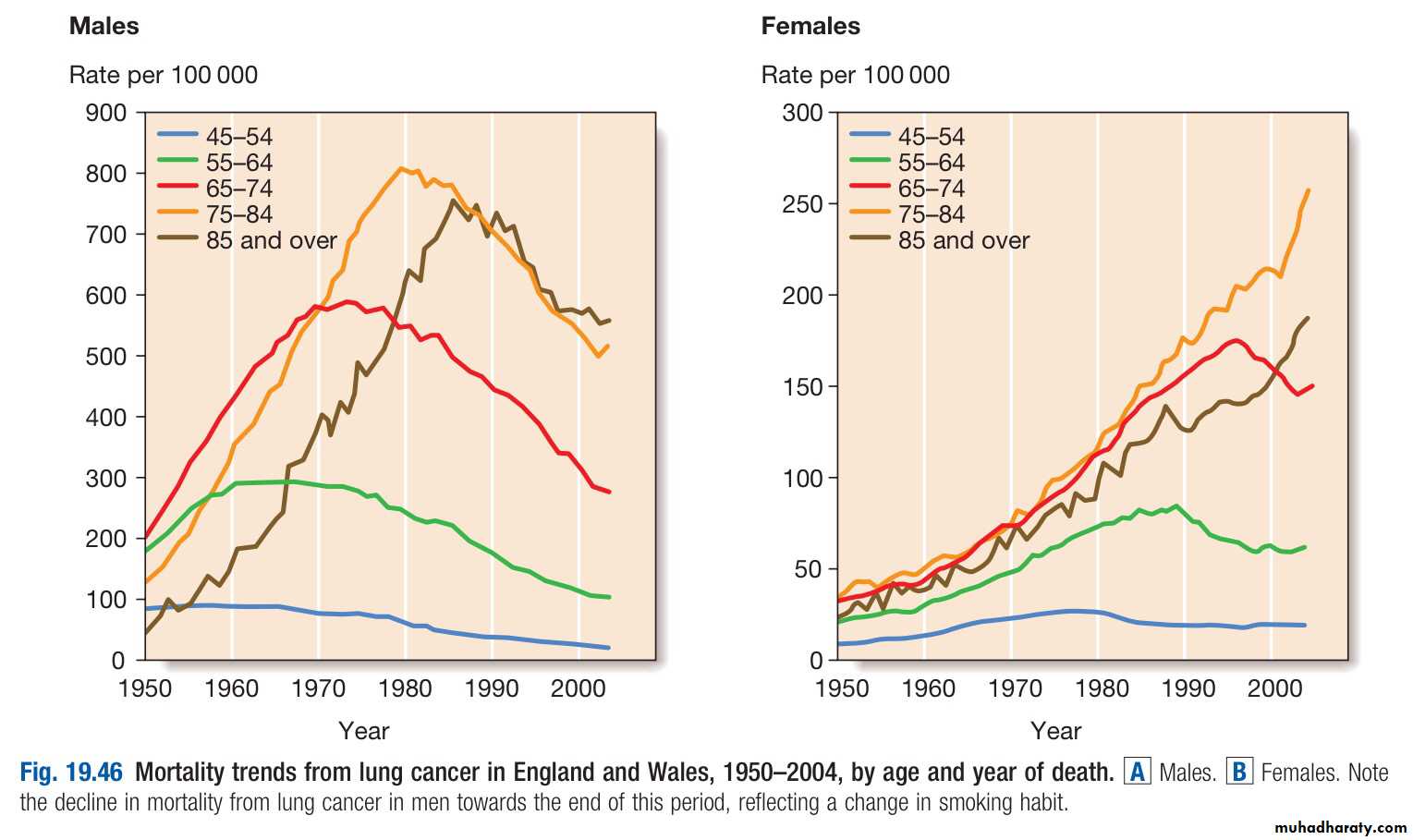

The incidence of bronchial carcinoma increased dramatically during the 20th century as a direct result of the tobacco epidemic.

In women, smoking prevalence and deaths from lung cancer continue to increase, and more women now die of lung cancer than breast cancer in the USA and the UK

Clinical features

Lung cancer presents in many different ways, reflecting local, metastatic or paraneoplastic tumour effects.Cough

This is the most common early symptom. It is often dry but secondary infection may cause purulent sputum.A change in the character of a smoker’s cough, particularly if associated with other new symptoms, should always raise suspicion of bronchial carcinoma

Haemoptysis

Haemoptysis is common, especially with central bronchial tumours.

Occasionally, central tumours invade large vessels, causing sudden massive haemoptysis that may be fatal

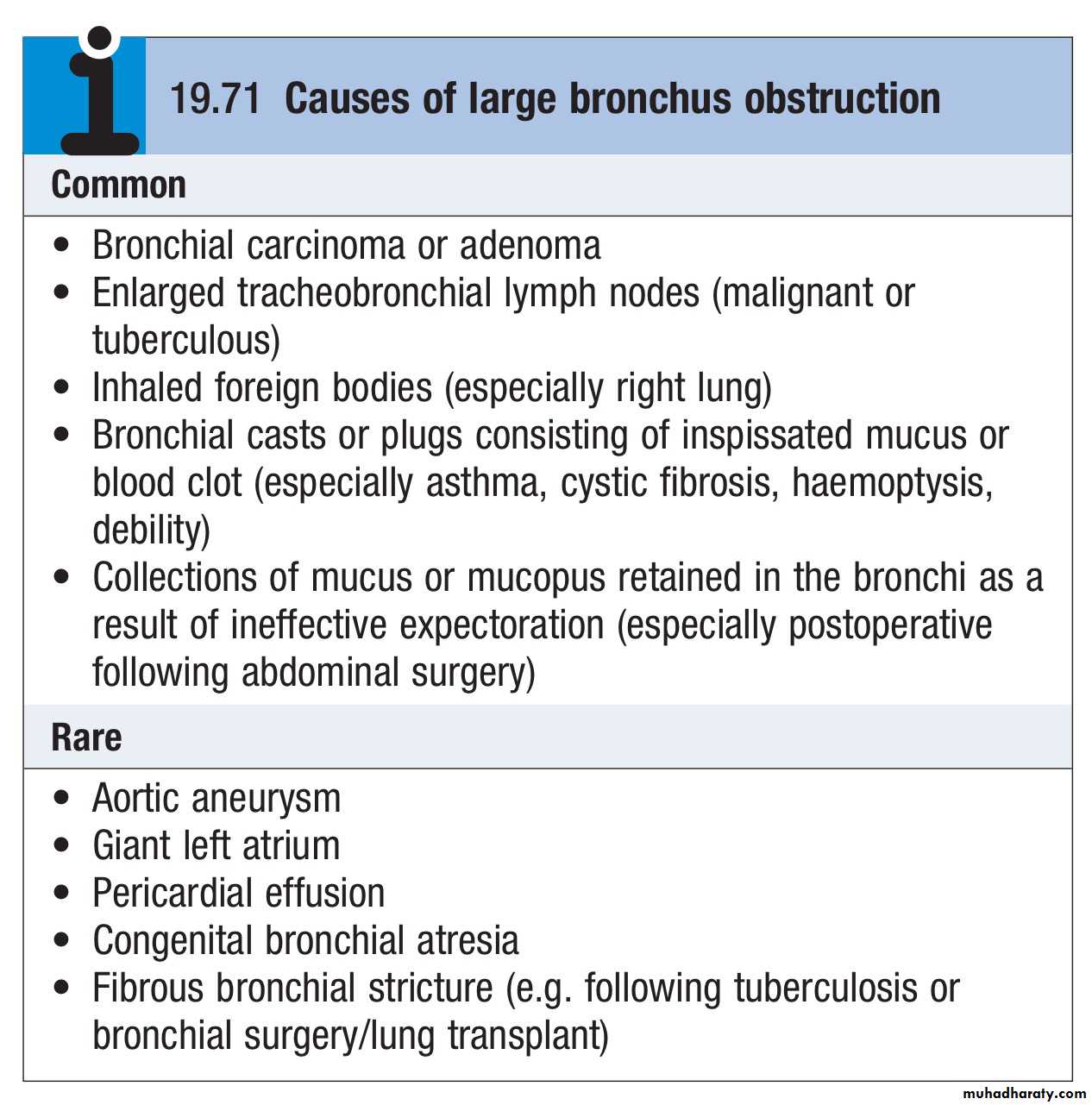

Bronchial obstruction

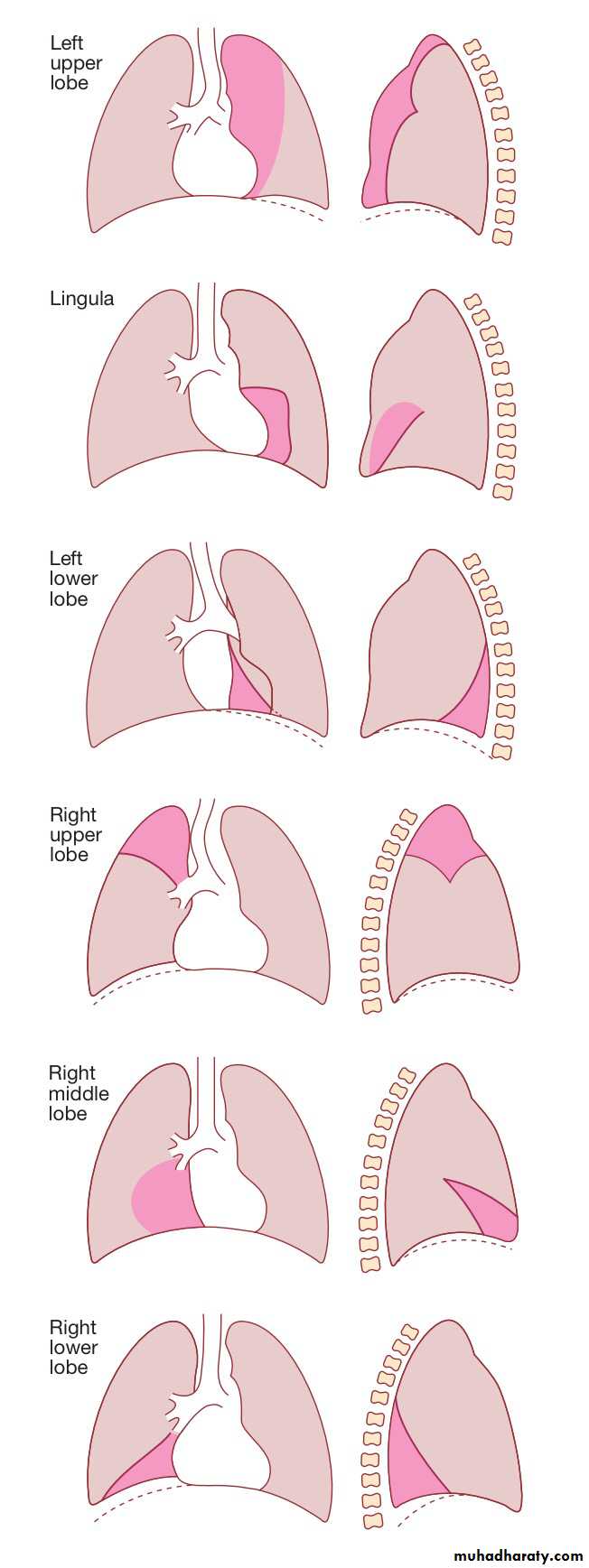

This is another common presentation, and the clinical and radiologicalmanifestations depend on the site and extent of the obstruction, any secondary infection, and the extent of coexisting lung disease.

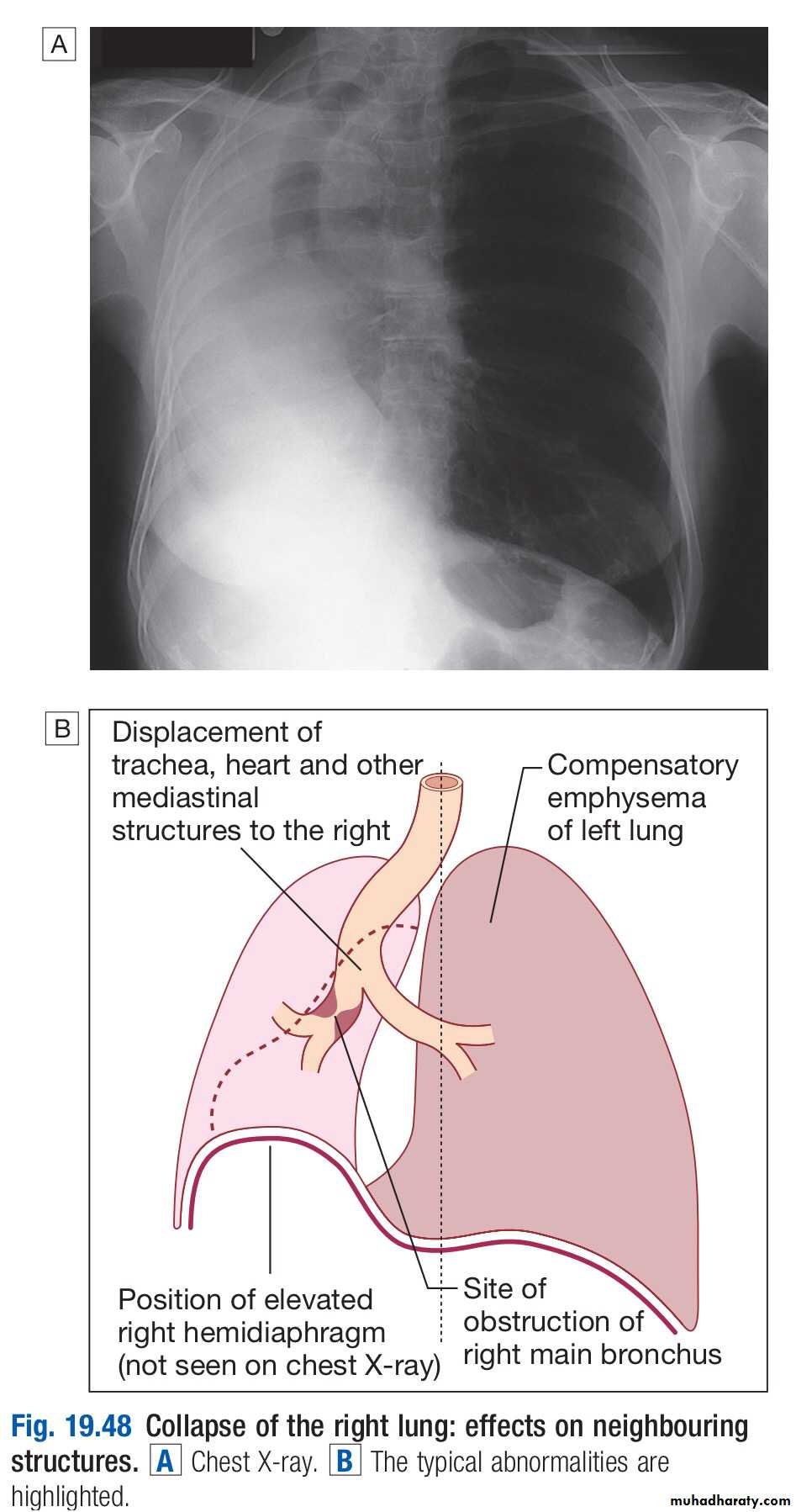

Complete obstruction causes collapse of a lobe or lung, with breathlessness, mediastinal displacement and dullness to percussion with reduced breath sounds.

Partial bronchial obstruction may cause a monophonic, unilateral wheeze that fails to clear with coughing, and may also impair the drainage of secretions to cause pneumonia or lung abscess as a presenting problem.

Pneumonia that recurs at the same site or responds slowly to treatment,

particularly in a smoker, should always suggest an underlying bronchial carcinoma.Stridor (a harsh inspiratory noise) occurs when the larynx, trachea or a main bronchus is narrowed by the primary tumour or by compression from malignant enlargement of the subcarinal and paratracheal lymph nodes.

Radiological features of lobar collapse caused by bronchial obstruction.

The dotted line in the drawings represents thenormal position of the diaphragm.

The dark pink area represents the extent

of shadowing seen on the X-ray.

Breathlessness

Breathlessness may be caused by collapse or pneumonia, or by tumour causing a large pleural effusion or compressing a phrenic nerve and leading to diaphragmatic paralysisPain and nerve entrapment

Pleural pain usually indicates malignant pleural invasion, although it can occur with distal infection. Intercostal nerve involvement causes pain in the distribution of a thoracic dermatome.Carcinoma in the lung apex may cause Horner’s syndrome (ipsilateral partial ptosis, enophthalmos, miosis and hypohidrosis of the face ) due to involvement of the sympathetic chain at or above the stellate ganglion.

Pancoast’s syndrome (pain in the inner aspect of the arm, sometimes with small muscle wasting in the hand) indicates malignant destruction of the T1 and C8 roots in the lower part of the brachial plexus by an apical lung tumour.

Mediastinal spread

Involvement of the oesophagus may cause dysphagia.If the pericardium is invaded, arrhythmia or pericardial effusion may occur.

Superior vena cava obstruction by malignant nodes causes swelling of the neck and face, conjunctival oedema, headache and dilated veins on the chest wall, and is most commonly due to bronchial carcinoma.

Involvement of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve by tumours at the left hilum causes vocal cord paralysis, voice alteration and a ‘bovine’ cough (lacking the normal explosive character).

Supraclavicular lymph nodes may be palpably enlarged or identified using ultrasound; if so, a needle aspirate may provide a simple means of cytological diagnosis

Metastatic spread

This may lead to focal neurological defects, epileptic seizures, personality change, jaundice, bone pain or skin nodules. Lassitude, anorexia and weight loss usually indicate metastatic spread

Finger clubbing.

Overgrowth of the soft tissue of the terminal phalanx, leading to increased nail curvature and nail bed fluctuation, is often seenHypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA)

This is a painful periostitis of the distal tibia, fibula, radius and ulna, with local tenderness and sometimes pitting oedema over the anterior shin. X-rays reveal subperiosteal new bone formation.While most frequently associated with bronchial carcinoma, HPOA can occur with other tumours

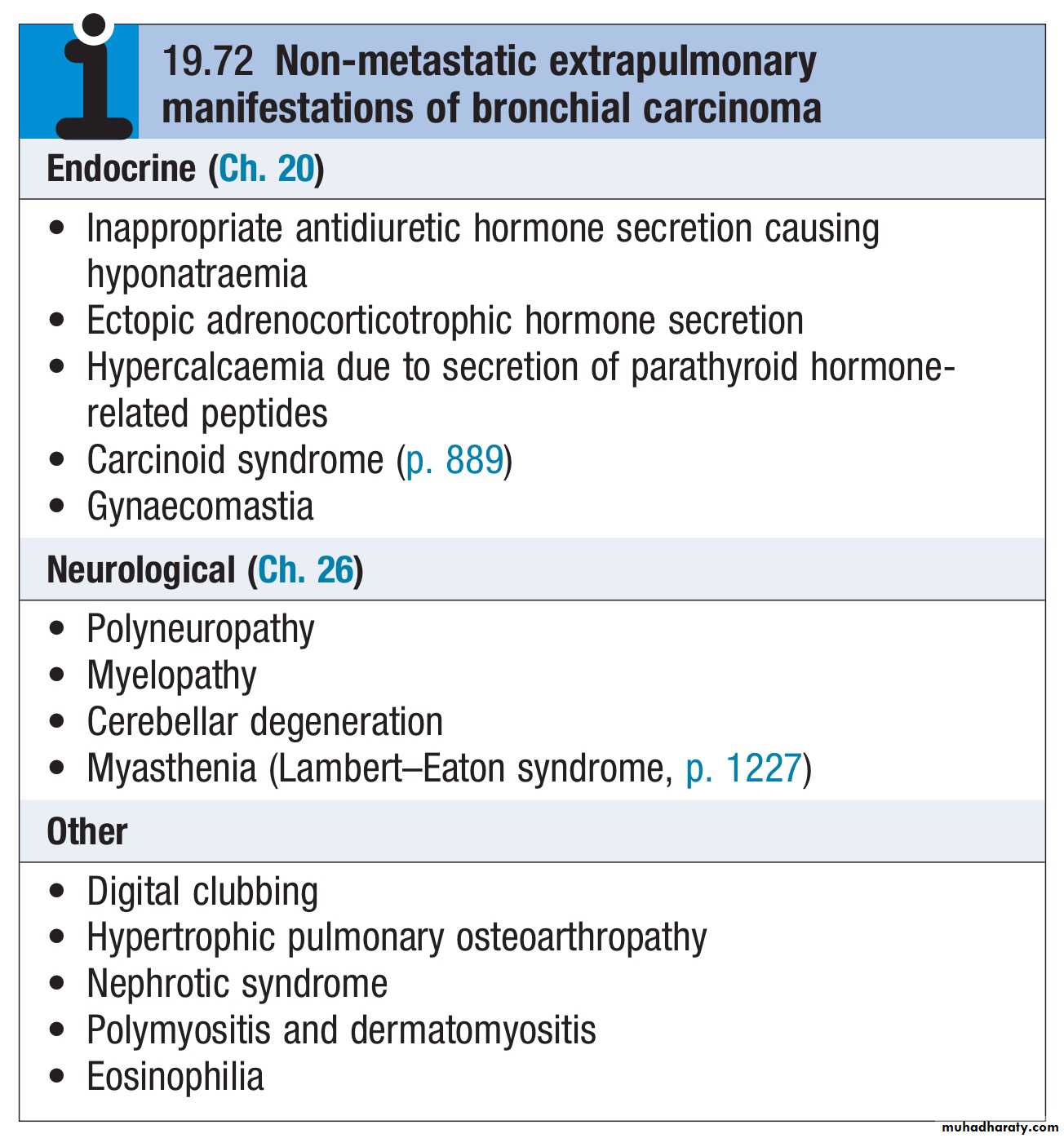

Non-metastatic extrapulmonary effects

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion and ectopic adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion are usually associated with small-cell lung cancer.Hypercalcaemia may indicate malignant bone destruction or production of hormone-like peptides by a tumour.

Associated neurological syndromes may occur with any type of bronchial carcinoma

Investigations

The main aims of investigation are :

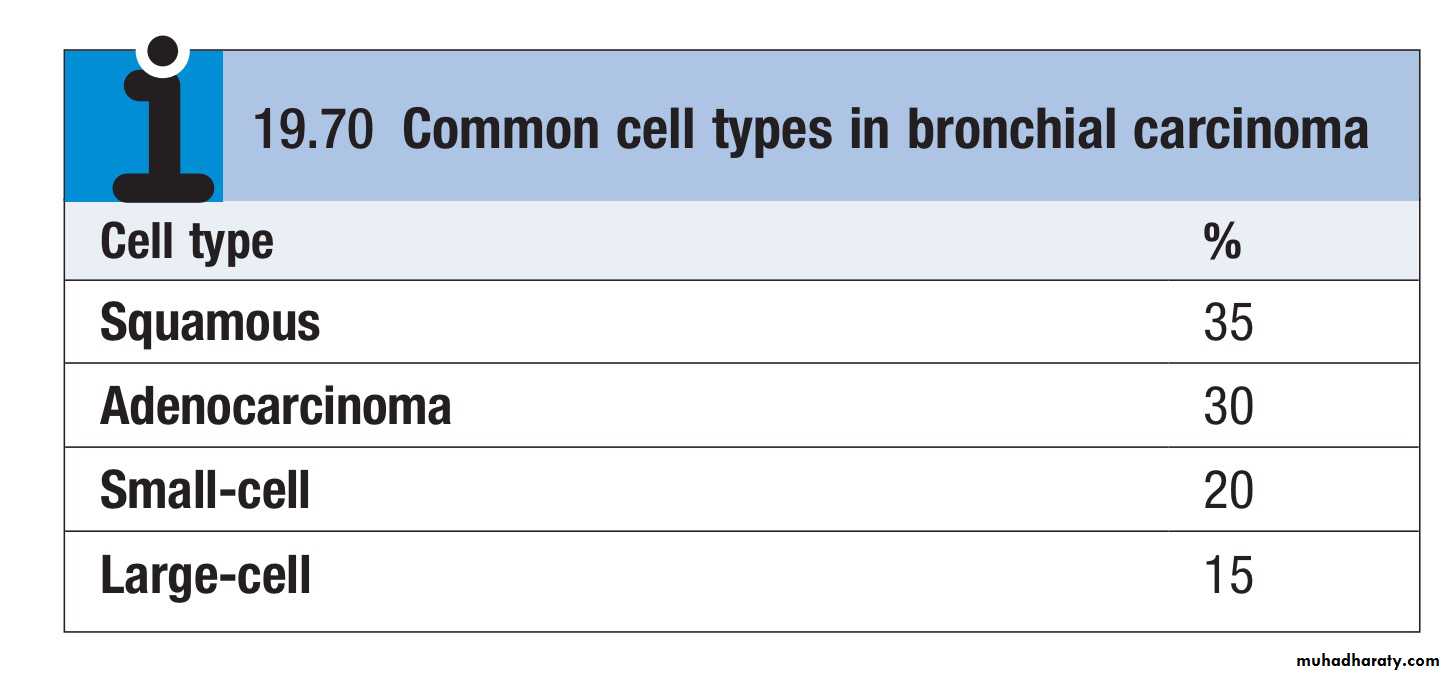

To confirm the diagnosisTo establish the histological cell type

To define the extent of the disease

Imaging

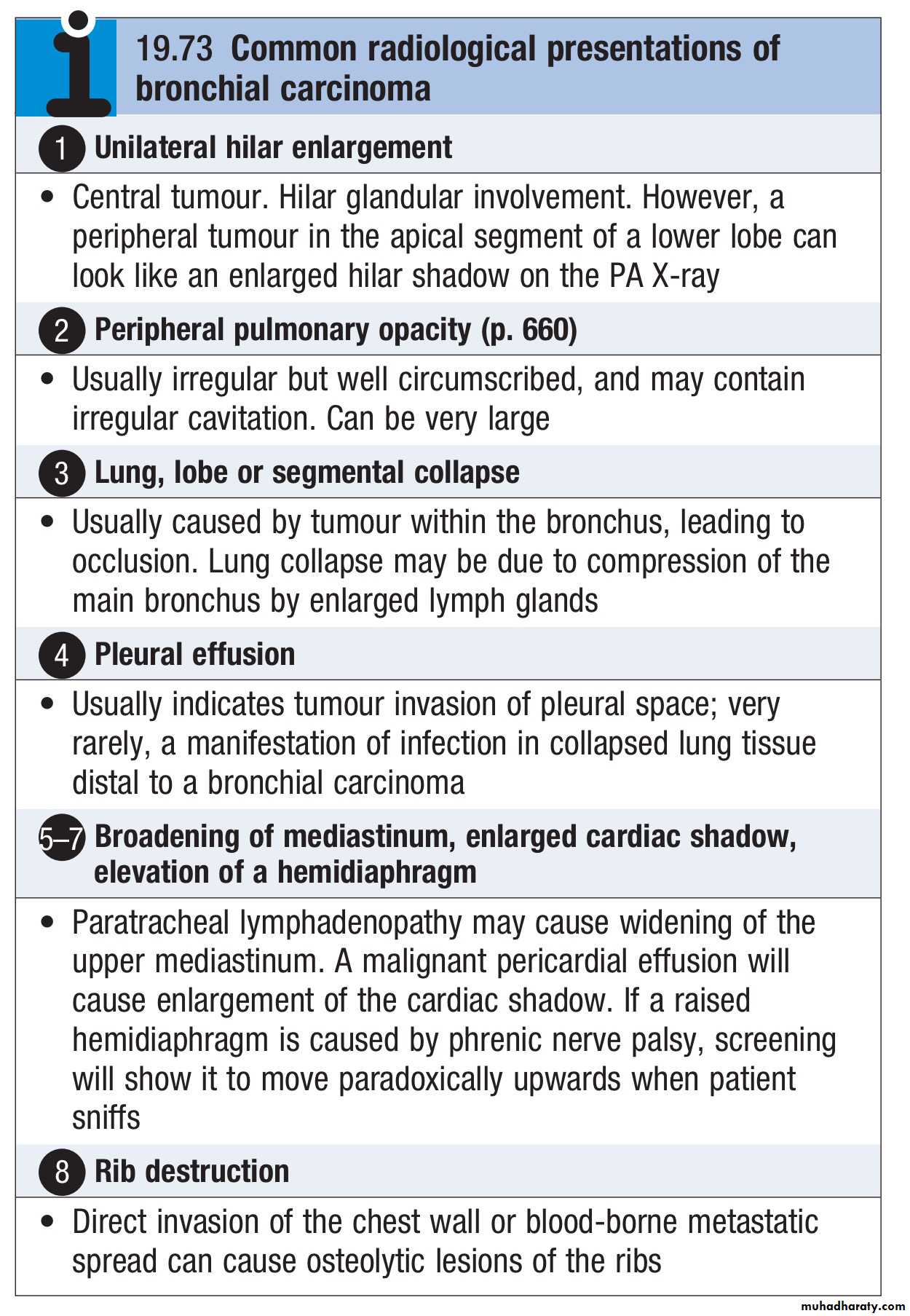

Bronchial carcinoma produces a range of appearances on chest X-ray, from lobar collapse to mass lesions, effusion or malignant rib destructionCT should be performed early as it may reveal mediastinal or metastatic spread and is helpful for planning biopsy procedures

Biopsy and histopathology

Around three-quarters of primary lung tumours can be visualised and sampled directly by biopsy and brushing using a flexible bronchoscope.Bronchoscopy also allows an assessment of operability, from the proximity of central tumours to the main carina

For tumours which are too peripheral to be accessible by bronchoscope, the yield of ‘blind’ bronchoscopic washings and brushings from the radiologically affected area is low, and percutaneous needle biopsy under CT or ultrasound guidance is a more reliable way to obtain a histological diagnosis.

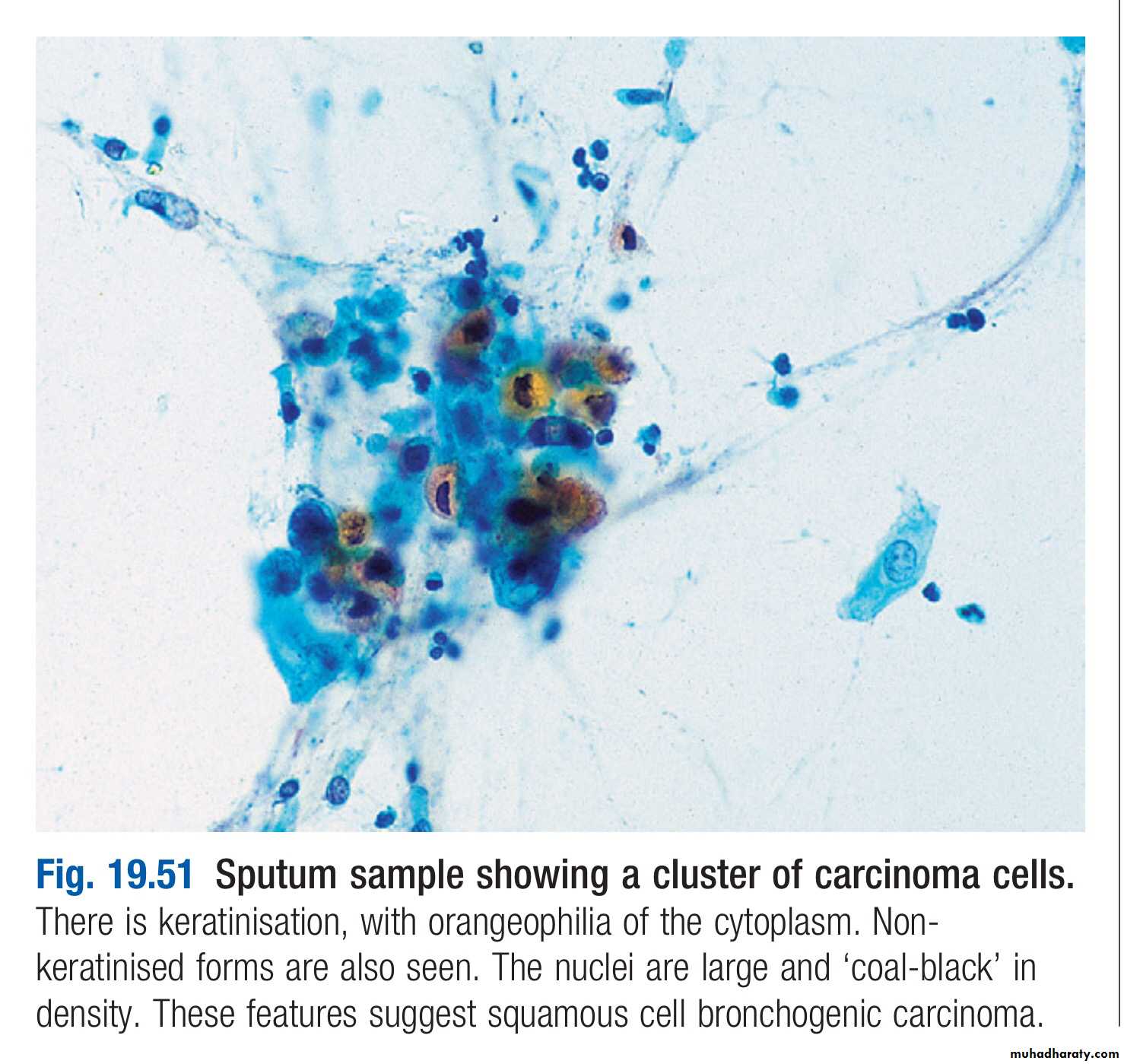

In patients who are unfit for invasive investigation, sputum cytology can reveal malignant cells although the yield is low

In patients with pleural effusions, pleural aspiration and biopsy is the preferred investigation.

Where facilities exist, thoracoscopy increases yield by allowing targeted biopsies under direct vision.

In patients with metastatic disease, the diagnosis can often be confirmed by needle aspiration or biopsy of affected lymph nodes, skin lesions, liver or bone marrow

Staging to guide treatment

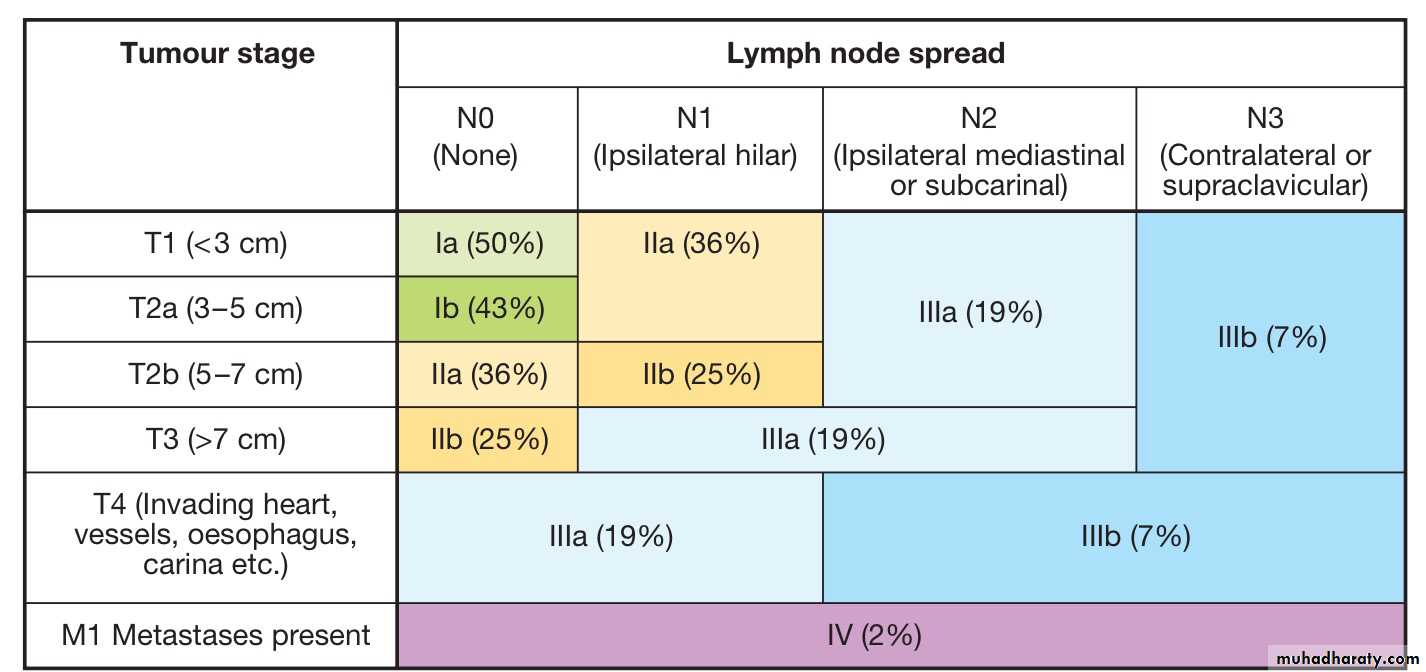

The propensity of small-cell lung cancer to metastasise early dictates that patients with this are usually not suitable for surgical intervention.In patients with non-small-cell cancer, appropriate treatment and prognosis are determined by disease extent, so careful staging is required.

CT scanning is used early to detect obvious local or distant spread.

Enlarged upper mediastinal nodes may be sampled using a bronchoscope equipped with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) or by mediastinoscopy. Nodes in the lower mediastinum can be sampled through the oesophageal wall using endoscopic ultrasound.

Combined CT and PET imaging is used increasingly to detect metabolically active tumour metastases.

Head CT, radionuclide bone scanning, liver ultrasound and bone marrow biopsy are generally reserved for patients with clinical, haematological or biochemical evidence of tumour spread to these sites.

• Information on tumour size and nodal and metastatic spread is then collated to assign the patient to one of seven staging groups that determine optimal management and prognosis

• Detailed physiological testing is required to assess whether the patient’s respiratory and cardiac function is sufficient to allow aggressive treatment