1

Fifth stage

Medicine

Lec-1

د.عبد هللا

26/3/2017

Stroke

The main arterial supply of the brain comes from the internal carotid

arteries, which supply the anterior brain, and the vertebral and basilar

arteries (vertebrobasilarsystem), which provide the posterior circulation.

The anterior and middle cerebral arteries supply the frontal and parietal

lobes, while the posterior cerebral artery supplies the occipital lobe.

The vertebral and basilar arteries perfuse the brain stem, mid-brain and

cerebellum.

Communicating arteries provide connections between the anterior and

posterior circulations and between left and right hemispheres, creating

protective anastomotic connections that form the circle of Willis.

2

In health, regulatory mechanisms maintain a constant cerebral blood flow

across a wide range of arterial blood pressures to meet the high resting

metabolic activity of brain tissue; cerebral blood vessels dilate when

systemic blood pressure is lowered and constrict when it is raised , This

autoregulatory mechanism can be disrupted after stroke

Definition:

Cerebrovascular disease is the third most common cause of death in the

developed world after cancer and ischaemic heart disease, and is the most

common cause of severe physical disability.

Cerebrovascular diseases include: ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke,

and cerebrovascular anomalies such as (intracranial aneurysms and

arteriovenous malformations (AVMs)).

The incidence of cerebrovascular diseases increases with age.

It is define by its abrupt onset of a neurologic deficit that is attributable

to a focal vascular cause ,most commonly( a hemiplegia with or without

signs of focal higher cerebral dysfunction (such as aphasia), hemisensory

loss, visual field defect or brain-stem deficit)

Cerebral ischemia is caused by a reduction in blood flow that lasts longer

than several seconds.

Neurologic symptoms are manifest within seconds because neurons lack

glycogen, so energy failure is rapid.

If the cessation of flow lasts for more than a few minutes, infarction or

death of brain tissue results; When blood flow is quickly restored, brain

tissue can recover fully and the patient’s symptoms are only transient:

This is called a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

3

TIA requires that all neurologic signs and symptoms resolve within 24 ;

stroke has occurred if the neurologic signs and symptoms last for >24 h.

generalized reduction in cerebral blood flow due to systemic hypotension

(e.g., cardiac arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, or hemorrhagic shock)

usually produces syncope ;If low cerebral blood flow persists for a longer

duration, then infarction in the border zones between the major cerebral

artery distributions may develop ;In more severe instances, global

hypoxia-ischemia causes widespread brain injury is called hypoxic-

ischemic encephalopathy .

Focal ischemia or infarction, is usually caused by thrombosis of the

cerebral vessels themselves or by emboli from a proximal arterial source

or the heart.

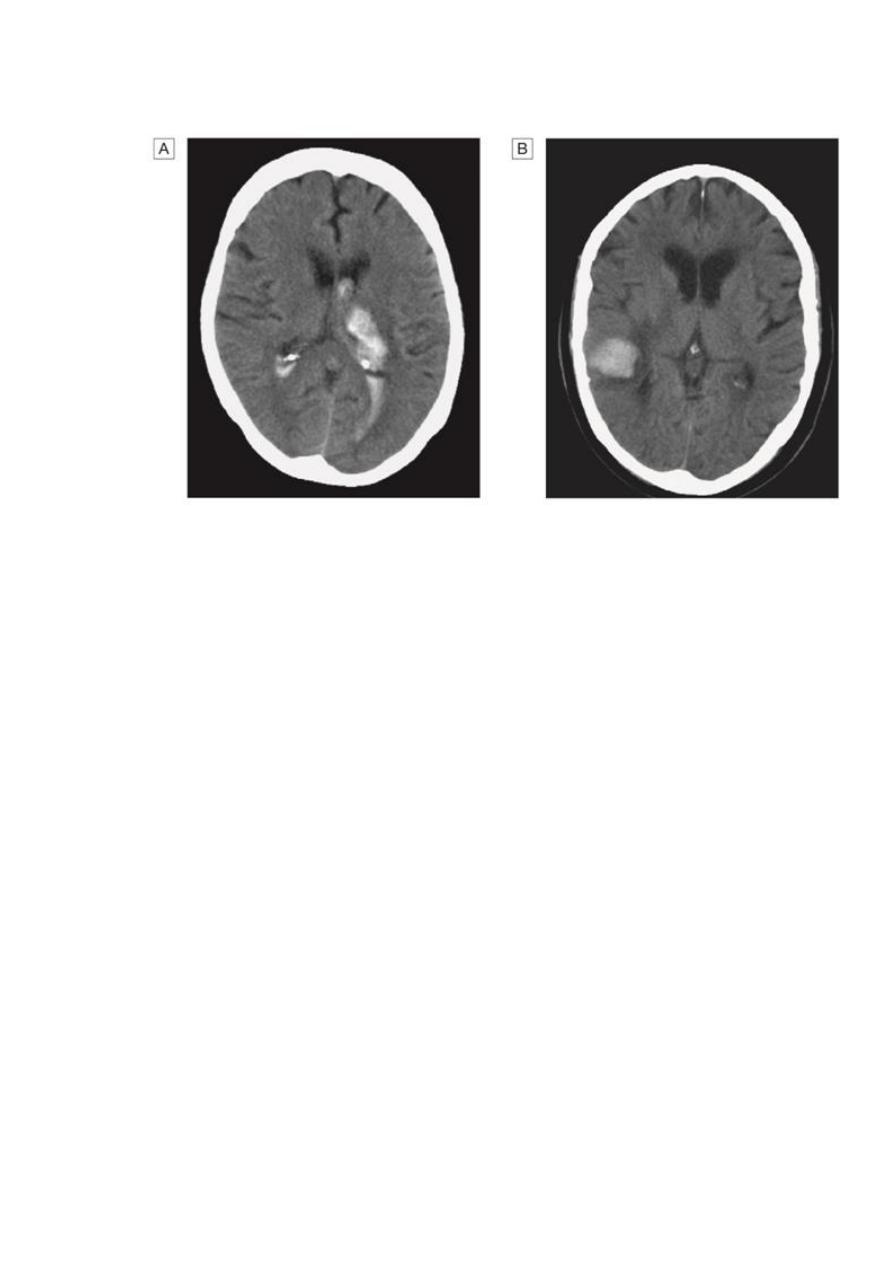

Intracranial hemorrhage is caused by bleeding directly into or around the

brain; it produces neurologic symptoms by producing a mass effect on

neural structures, from the toxic effects of blood itself, or by increasing

intracranial pressure.

Progressing stroke (or stroke in evolution): This describes a stroke in which

the focal neurological deficit worsens after the patient first presents. may be

due to increasing volume of infarction, haemorrhagic transformation or

increasing oedema.

Completed stroke: This describes a stroke in which the focal deficit persists

and is not progressing.

4

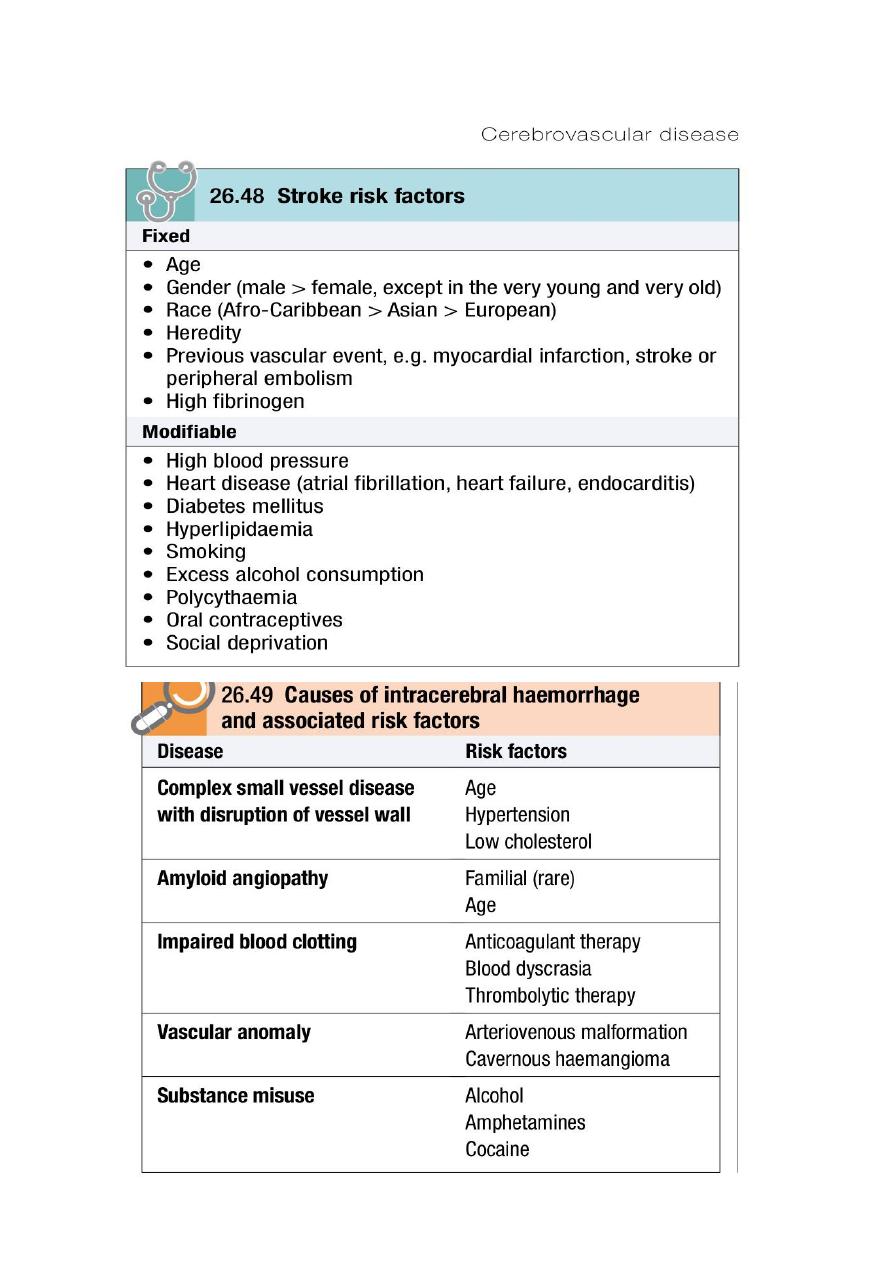

Pathophysiology:

Of patients with a stroke, 85% will have a cerebral infarction and the

remainder will have had an intracerebral haemorrhage.

Brain imaging is required to distinguish these pathologies and to guide

management.

The combination of severe headache and vomiting at the onset of the

focal neurological deficits increases the likelihood of a haemorrhagic

stroke.

Cerebral infarction

is mostly due to thromboembolic disease secondary to atherosclerosis in

the major extracranial arteries (carotid artery and aortic arch).

About 20% of infarctions are due to embolism from the heart, and a

further 20% are due to intrinsic disease of small perforating vessels

(lenticulostriate arteries), producing so-called ‘lacunar’ infarctions.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

This usually results from rupture of a blood vessel within the brain

parenchyma but may also occur in a patient with a subarachnoid

hemorrhage if the artery ruptures into the subarachnoid space.

Hemorrhage frequently occurs into an area of brain infarction.

The haemorrhage itself may expand over the first minutes or hours, or it

may be associated with a rim of cerebral oedema, which, along with the

haematoma, acts like a mass lesion to cause progression of the

neurological deficit. If big enough, this can cause shift of the intracranial

contents, producing transtentorial coning and sometimes rapid death.

If the patient survives, the haematoma is gradually absorbed, leaving a

haemosiderinlined slit in the brain parenchyma.

5

6

Clinical features

:

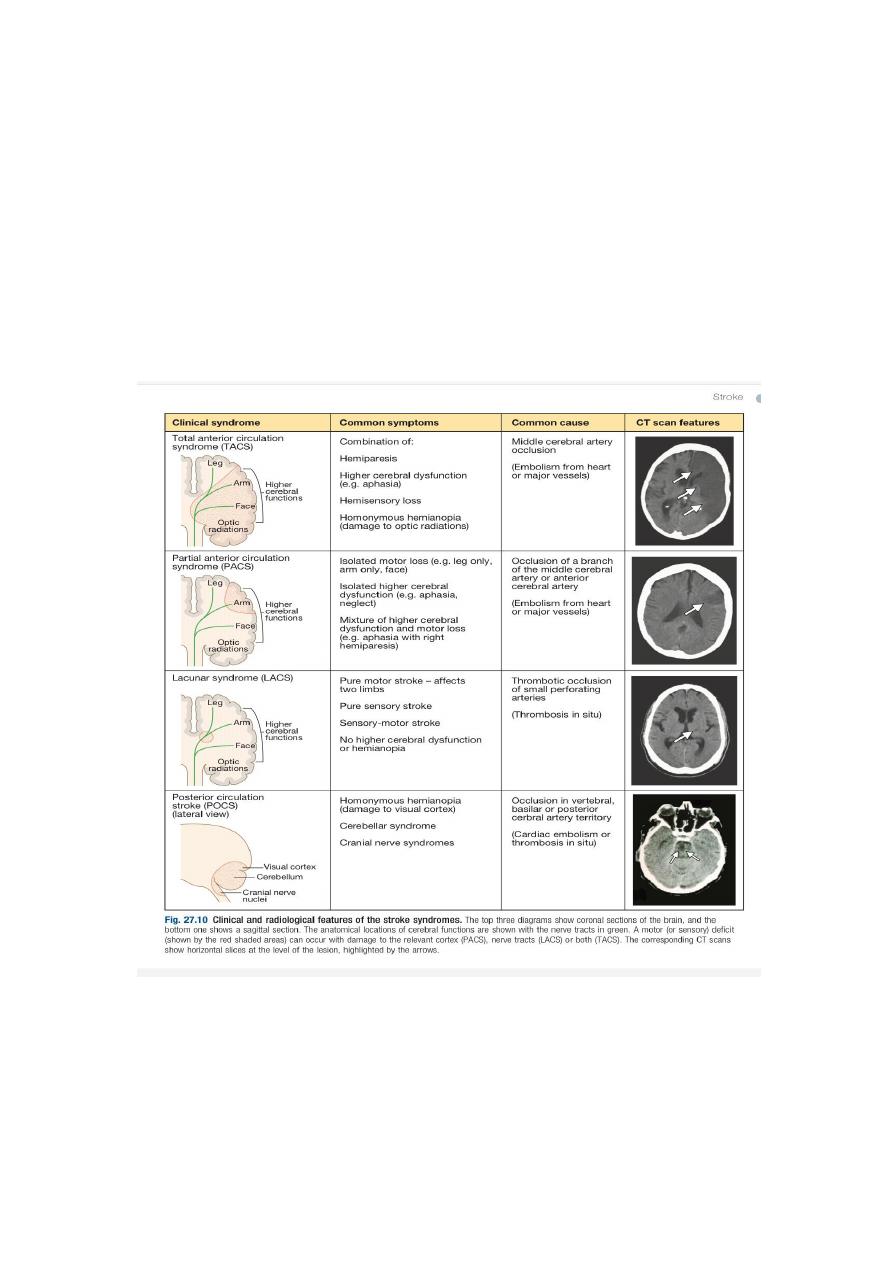

The clinical presentation of stroke depends upon which arterial territory is

involved and the size of the lesion.

The presence of a unilateral motor deficit, a higher cerebral function

deficit such as aphasia or neglect, or a visual field defect usually places the

lesion in the cerebral hemisphere.

Ataxia, diplopia, vertigo and/or bilateral weakness usually indicate a

lesion in the brain stem or cerebellum.

Reduced conscious level usually indicates a large volume lesion in the

cerebral hemisphere but may result from a lesion in the brain stem or

complications such as obstructive hydrocephalus, hypoxia or severe

systemic infection.

Clinical assessment of the patient with a stroke should also include a

general examination since this may provide clues to the cause of the

stroke, and identify important comorbidities and complications of the

stroke.

7

Investigations:

aims to confirm the vascular nature of the lesion, distinguish cerebral

infarction from haemorrhage and identify the underlying vascular disease

and risk factors

Initial investigation of all patients with stroke includes a range of simple

blood tests to detect common vascular risk factors and markers of rarer

causes, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and brain imaging. Where there is

uncertainty about the nature of the stroke, further investigations are

usually indicated

Neuroimaging :

Brain imaging with either CT or MRI should be performed in all patients

with acute stroke.

CT is the most practical and widely available method of imaging the brain.

It will usually exclude non- stroke lesions, including subdural haematomas

and brain tumours, and will demonstrate intracerebral haemorrhage

within minutes of stroke onset However, especially within the first few

hours after symptom onset, CT changes in cerebral infarction may be

completely absent or only very subtle.

MRI diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) can detect ischaemia earlier than

CT.

MRI is more sensitive than CT in detecting strokes affecting the brain stem

and cerebellum.

CT and MRI may reveal clues as to the nature of the arterial lesion. For

example, there may be a small, deep lacunar infarct indicating small-

vessel disease, or a more peripheral infarct suggesting an extracranial

source of embolism.

In a haemorrhagic lesion, the location might indicate the presence of an

underlying vascular malformation, saccular aneurysm or amyloid

angiopathy

8

Cardiac investigations:

Approximately 20% of ischaemic strokes are due to embolism from the

heart. The most common causes are atrial fibrillation, prosthetic heart

valves, other valvular abnormalities and recent myocardial infarction.

These can often be identified by clinical examination and ECG.

A transthoracic or transoesophageal echocardiogram can be useful, either

to confirm the presence of cardiac source or to identify an unsuspected

source such as endocarditis, atrial myxoma, intracardiac thrombus or

patent foramen ovale. Such findings may lead on to specific treatment .

Vascular imaging:

Many ischaemic strokes are caused by atherosclerotic thromboembolic

disease of the major extracranial vessels(arterial to arterial emboli).

Detection of extracranial vascular disease can help establish why the

patient has had an ischaemic stroke and may lead to specific treatments

including carotid endarterectomy to reduce the risk of further stroke.

Extracranial arterial disease can be non-invasively identified with duplex

ultra sound, MR angiography (MRA) or CT angiography.

Management:

is aimed at minimizing the volume of brain that is irreversibly damaged,

preventing complications

reducing the patient’s disability and handicap through rehabilitation,

and reducing the risk of recurrent episodes

9

The patient’s neurological deficits may worsen during the first few hours

or days after their onset. This is may be due to extension of the area of

infarction, hemorrhage into it, or the development of oedema with

consequent mass effect.

It is important to distinguish such patients from those who are

deterioratin as a result of complications such as hypoxia, sepsis, epileptic

seizures or metabolic abnormalities which can be easily reversed .

11

Management of acute stroke

:

Airway

Perform bedside swallow screen and keep patient nil by mouth if

swallowing unsafe or aspiration occurs.

Breathing

Check respiratory rate and oxygen saturation and give oxygen if

saturation < 95%.

Circulation

Check peripheral perfusion, pulse and blood pressure and treat

abnormalities with fluid replacement, antiarrhythmics and inotropic drugs

as appropriate.

Hydration

If signs of dehydration, give fluids parenterally or by nasogastric tube

11

Nutrition.

Assess nutritional status and provide nutritional supplements if necessary

If dysphagia persists for > 48 hrs, start feeding via a nasogastric tube.

Blood pressure

• Unless there is heart or renal failure, evidence of hypertensive

encephalopathy or aortic dissection, do not lower blood pressure in first

week as it may reduce cerebral perfusion. Blood pressure often returns

towards patient’s normal level within first few days.

Blood glucose

• Check blood glucose and treat when levels are ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (200

mg/dL)

• Monitor closely to avoid hypoglycemia.

Temperature

• If pyrexic, investigate and treat underlying cause

• Control with antipyretics, as raised brain temperature may increase

infarct volume

Incontinence

Check for constipation and urinary retention; treat appropriately

Avoid urinary catheterisation unless patient is in acute urinary retention or

incontinence is threatening pressure areas

12

treatments in acute stroke:

Thrombolysis:

Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen

activator (rt-PA) increases the risk of haemorrhagic transformation

of the cerebral infarct with potentially fatal results. However, if it is

given within 4.5 hours of symptom onset to carefully selected

patients, the haemorrhagic risk is offset by an improvement in

overall outcome

The earlier treatment is given, the greater the benefit.

Aspirin:

In the absence of contraindications, aspirin (300 mg daily) should be

started immediately after an ischaemic stroke unless rt-PA has been

given, in which case it should be withheld for at least 24 hours.

Aspirin reduces the risk of early recurrence and has a small but

clinically worthwhile effect on long-term outcome

it may be given by rectal suppository or by nasogastric tube in

dysphagic patients.

Heparin:

routine use of heparin does not result in better long-term out-

comes, and therefore it should not be used in the routine

management of acute stroke.

heparin might provide benefit in selected patients, such as those

with recent myocardial infarction, arterial dissection or progressing

strokes. Intracranial haemorrhage must be excluded on brain

imaging before considering anticoagulation.

13

Coagulation abnormalities:

In those with intracerebral haemorrhage, coagulation abnormalities

should be reversed as quickly as possible to reduce the likelihood of

the haematoma enlarging. This most commonly arises in those on

warfarin therapy.

Management of risk factors:

Patients with ischaemic events should be put on long- term

antiplatelet drugs and statins to lower cholesterol.

For patients in atrial fibrillation, the risk can be reduced by about

60% by using oral anticoagulation to achieve an INR of 2–3.

The risk of recurrence after both ischaemic and haemorrhagic

strokes can be reduced by blood pressure reduction, even for those

with relatively normal blood pressures

Carotid endarterectomy and angioplasty:

Surgery is most effective in patients with more severe stenoses (70–

99%) and in those in whom it is performed within the first couple of

weeks after the TIA or ischaemic stroke.

Patients with cerebellar haematomas or infarcts with mass effect

may develop obstructive hydrocephalus and some will benefit from

insertion of a ventricu- lar drain and/or decompressive surgery.

Some patients with large haematomas or infarction with massive

oedema in the cerebral hemispheres may benefit from anti-oedema

agents, such as mannitol or artificial ventilation, and surgical

decompression to reduce intracranial pressure should be

considered in appropriate patients.

14

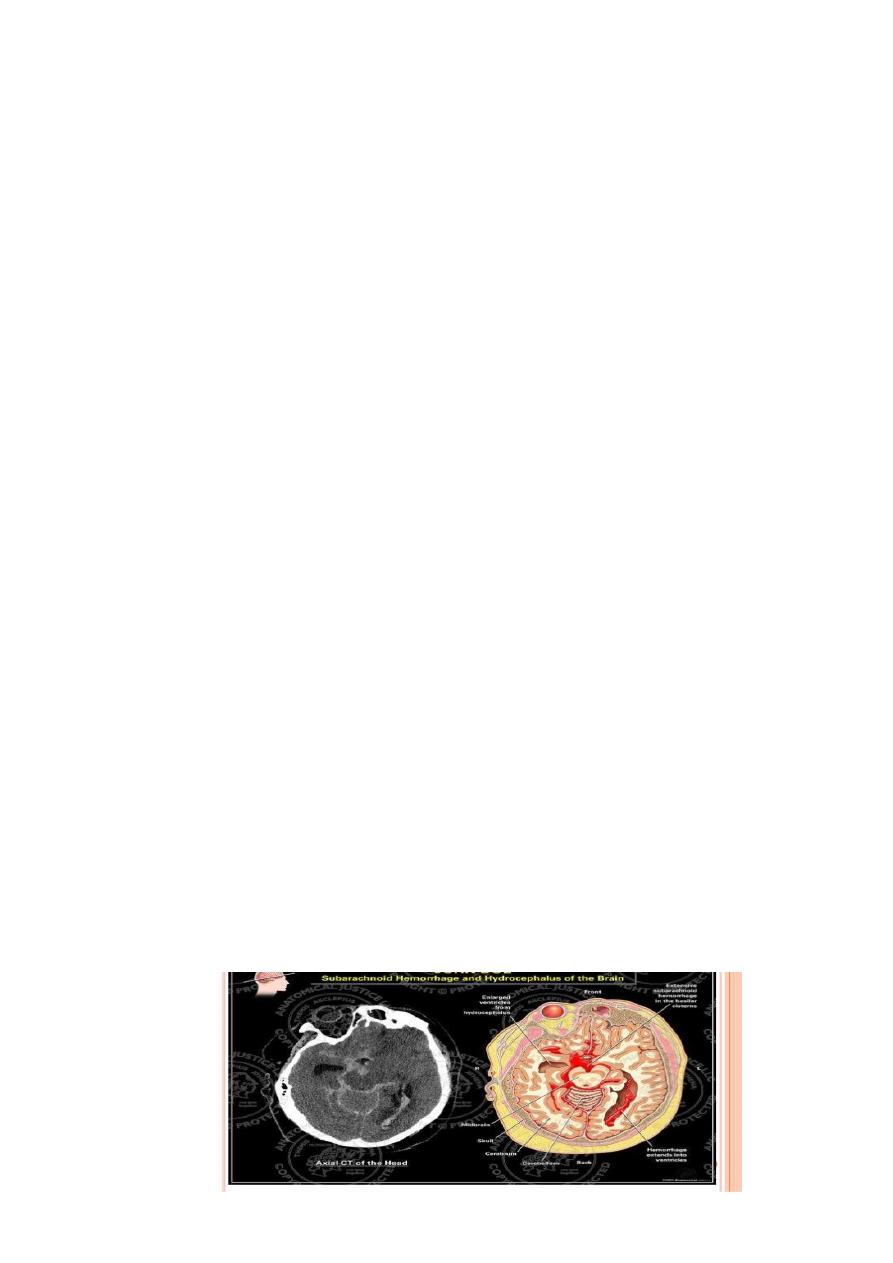

SUBARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE :

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is less common than ischaemic

stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage.

Women are affected more commonly than men and the condition

usually presents before the age of 65.

The immediate mortality of aneurysmal SAH is about 30%; survivors

have a recurrence (or rebleed) rate of about 40% in the first 4

weeks and 3% annually thereafter.

85% of SAH are caused by saccular or ‘berry’ aneurysms arising from

the bifurcation of cerebral arteries , particularly in the region of the

circle of Willis.

There is an increased risk in first-degree relatives of those with

saccular aneurysms, and in patients with polycystic kidney disease

and congenital connective tissue defects such as Ehlers– Danlos

syndrome.

In about 10% of cases, SAH are non-aneurysmal haemorrhages (so-

called peri- mesencephalic haemorrhages).

Five percent of SAH are due to arteriovenous malformations and

vertebral artery dissection.

15

Clinical features:

SAH typically presents with a sudden, severe, ‘thunderclap’

headache (often occipital), which lasts for hours or even days, often

accompanied by vomiting, raised blood pressure and neck stiffness

or pain. It commonly occurs on physical exertion, straining and

sexual excitement

There may be loss of consciousness at the onset, so SAH should be

considered if a patient is found comatose.

On examination, the patient is usually distressed and irritable, with

photophobia. There may be neck stiffness due to subarachnoid

blood but this may take some hours to develop. Focal hemisphere

signs, such as hemiparesis or aphasia, may be present at onset if

there is an associated intracerebral haematoma.

A third nerve palsy may be present due to local pressure from an

aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery, but this is rare.

Investigations;

CT brain scanning and lumbar puncture are required.

The diagnosis of SAH can be made by CT, but a negative result does

not exclude it, since small amounts of blood in the subarachnoid

space cannot be detected by CT.

Lumbar puncture should be performed 12 hours after symptom

onset if possible, to allow detection of xanthochromia , If either of

these tests is posi- tive, cerebral angiography is required to

determine the optimal approach to prevent recurrent bleeding.

16

Management:

Good control of blood pressure < 160 systolic

Good hydration

Strong analgesia

Avoid constipation

Nimodipine (30–60 mg tab for 21 days to prevent delayed

ischaemia in the acute phase.

Insertion of coils into an aneurysm (via an endovascular procedure)

or surgical clipping of the aneurysm neck reduces the risk of both

early and late recurrence.

Arteriovenous malformations can be managed either by surgical

removal, by ligation of the blood vessels that feed or drain the

lesion, or by injection of material to occlude the fistula or draining

veins.

Treatment may also be required for complications of SAH, which

include non obstructive hydrocephalus (that may require drainage

via a shunt),

delayed cerebral ischaemia due to vasospasm (which may be

treated with vasodilators),

hyponatraemia (best managed by fluid restriction) and systemic

complications associated with immobility, such as chest infection

and venous thrombosis.

17

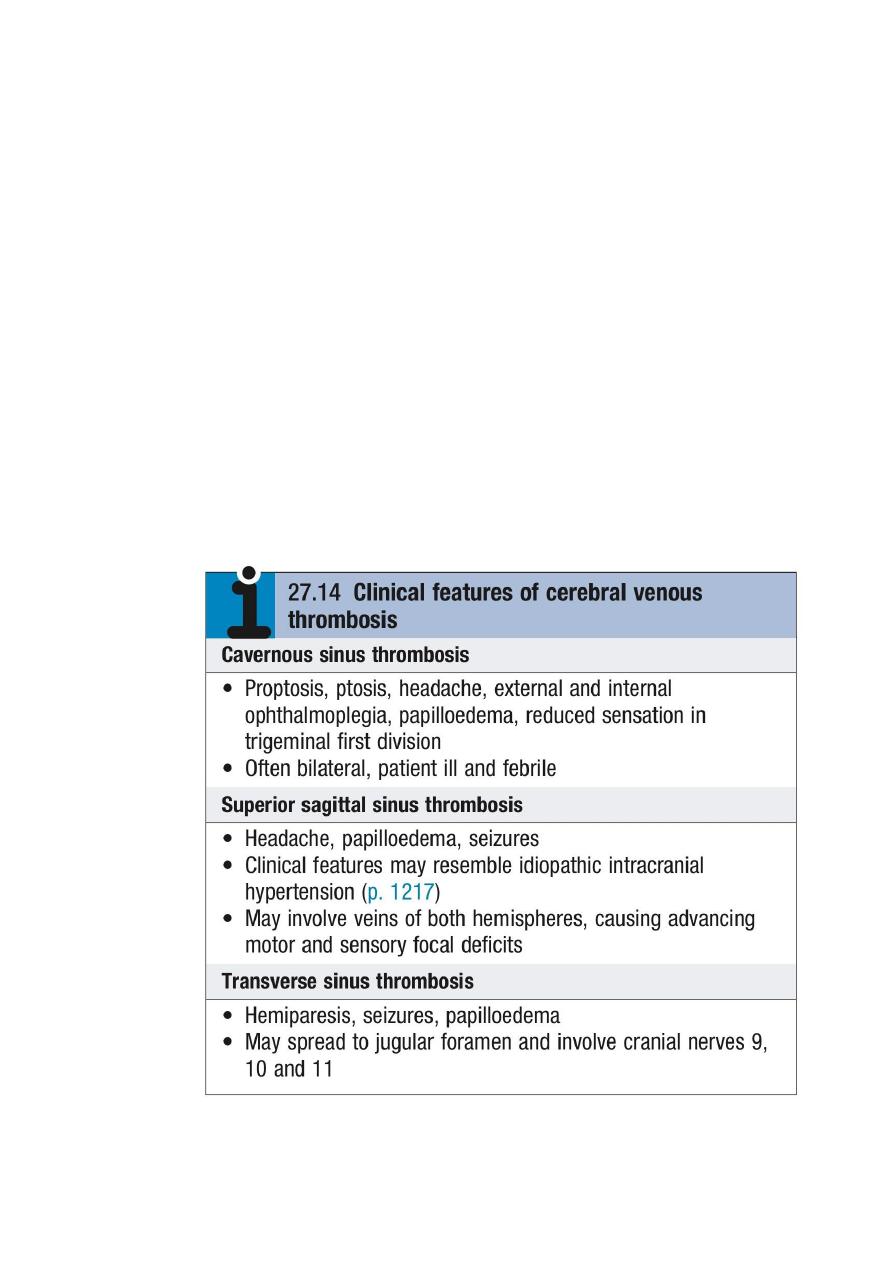

CEREBRAL VENOUS DISEASE:

Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and venous sinuses (cerebral

venous thrombosis) is much less common than arterial thrombosis.

Clinical features

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis usually presents with symptoms

of raised intracranial pressure, seizures and focal neurological

symptoms.

The clinical features vary according to the sinus involved , Cortical

vein thrombosis presents with focal cortical deficits such as aphasia

and hemiparesis (depending on the area affected), and epilepsy

(focal or generalised).

The deficit can increase if spreading thrombophlebitis occurs.

18

Causes of cerebral venous thrombosis:

Predisposing systemic causes:

• Dehydration

• Thrombophilia

• Pregnancy

• Hypotension

• eh et’s disease

• Oral contraceptive use

Local causes:

• Paranasal sinusitis

• Facial skin infection

• Meningitis, subdural empyema

• Otitis media, mastoiditis

• Skull fracture

• Penetrating head and eye wounds

19

Investigations and management:

MR venography demonstrates a filling defect in the affected vessel.

Anticoagulation, initially with heparin followed by warfarin, is

usually beneficial, even in the presence of venous haemorrhage.

In selected patients, the use of endovascular thrombolysis has been

advocated. Management of underlying causes and complications,

such as persistently raised intracranial pressure, is also important.

About 10% of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, particularly

cavernous sinus thrombosis, is associated with infection (most

commonly Staphylococcus aureus), which necessitates antibiotic

treatment.