Dr. Ahmed Saleem

FICMS

TUCOM / 3rd Year / 2015

PRINCIPLES OF ONCOLOGY

As the population ages, oncology is becoming a larger portion of surgical practice. The surgeon often is

responsible for the initial diagnosis and management of solid tumors. Knowledge of cancer epidemiology,

etiology, staging, and natural history is required for initial patient assessment, as well as to determination

of the optimal surgical therapy.

Definitions

Metaplasia: Reversible transformation of one type of terminally differentiated cell into another fully

differentiated cell type.

Dysplasia: Potentially premalignant condition characterized by increased cell growth, atypical morphology,

and altered differentiation.

Neoplasia: Autonomous abnormal growth of cells which persists after the initiating stimulus has been

removed.

A neoplasm (Tumor): is a lesion resulting from neoplasia.

Cancer: The name ‘cancer’ comes from the Greek and Latin words for a crab, and refers to the claw-like

blood vessels extending over the surface of an advanced breast cancer.

Benign tumors: Slow growing, usually encapsulated, do not metastasize, do not recur if completely

excised, and rarely endanger life. Effects are due to size and site. Histology: well differentiated, low

mitotic rate, resemble tissue of origin.

Malignant tumors (Cancer): These expand and infiltrate locally, encapsulation is rare, metastasize

to other organs via blood, lymphatics or body spaces, endanger life if untreated. Histology: varying

degrees of differentiation from tissue of origin, pleomorphic (variable cell shapes), high mitotic rate.

Cancer Biology

Cancer cells are psychopaths. They have no respect for the biological principles of normal cellular

organization. Their proliferation is uncontrolled; their ability to spread is unbounded. Their relentless

progress destroys first the tissue and then the person. In order to behave in such an unprincipled fashion,

cells have to acquire a number of characteristics before they are fully malignant. It has been proposed that

there are six essential alterations in cell physiology that dictate malignant growth: self-sufficiency of growth

signals, insensitivity to growth-inhibitory signals, evasion of apoptosis (programmed cell death), potential

for limitless replication, angiogenesis, and invasion and metastasis.

Invasion: is the most important single criterion for malignancy and is also responsible for clinical

signs and prognosis as well as dictating surgical management. Factors that enable tumors to

invade tissues include:

Increased cellular motility.

Loss of contact inhibition of migration and growth.

Secretion of proteolytic enzymes, such as collagenase, which weakens normal connective

tissue bonds.

Decreased cellular adhesion.

Page 1 of 8

Metastasis: is a consequence of the invasion property and is the process by which malignant

tumors spread from their site of origin (primary tumor) to form secondary tumors at distant

sites. The routes of metastasis are:

Hematogenous: via the bloodstream.

Lymphatic: to local, regional, and systemic nodes.

Transcelomic: across pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities.

Implantation: during surgery or along biopsy tracks.

Genetic abnormalities in tumors:

Two genetic mechanisms of carcinogenesis are proposed:

Oncogenes: Enhanced expression of stimulatory dominant genes.

Tumor suppressor genes: Inactivation of recessive inhibitory genes.

Examples include BRCA1, p53, k-ras, APC, DCC.

Malignant transformation:

The characteristics of the cancer cell arise as a result of mutation. Only very rarely is a single

mutation sufficient to cause cancer; multiple mutations are usually required. Cancer is usually

regarded as a clonal disease. Once a cell has arisen with all the mutations necessary to make it fully

malignant, it is capable of giving rise to an infinite number of identical cells, each of which is fully

malignant. These cells divide, invade, metastasize and destroy but, ultimately, each is the direct

descendant of that original, primordial, transformed cell.

Tumor growth:

Tumor doubling time depends on cell cycle time, growth function, and cell loss fraction. In tumors

such as leukemia, the doubling time remains remarkably constant: the cell mass increases

proportionally with time. This is exponential growth. In solid tumors, doubling time slows as size

increases. This is referred to as Gompertzian growth.

Etiology of Cancer

Both inheritance and environment are important determinants of cancer development. Although

environmental factors have been implicated in more than 80 per cent of cases, this still leaves plenty of

scope for the role of genetic inheritance (Inherited cancer syndromes).

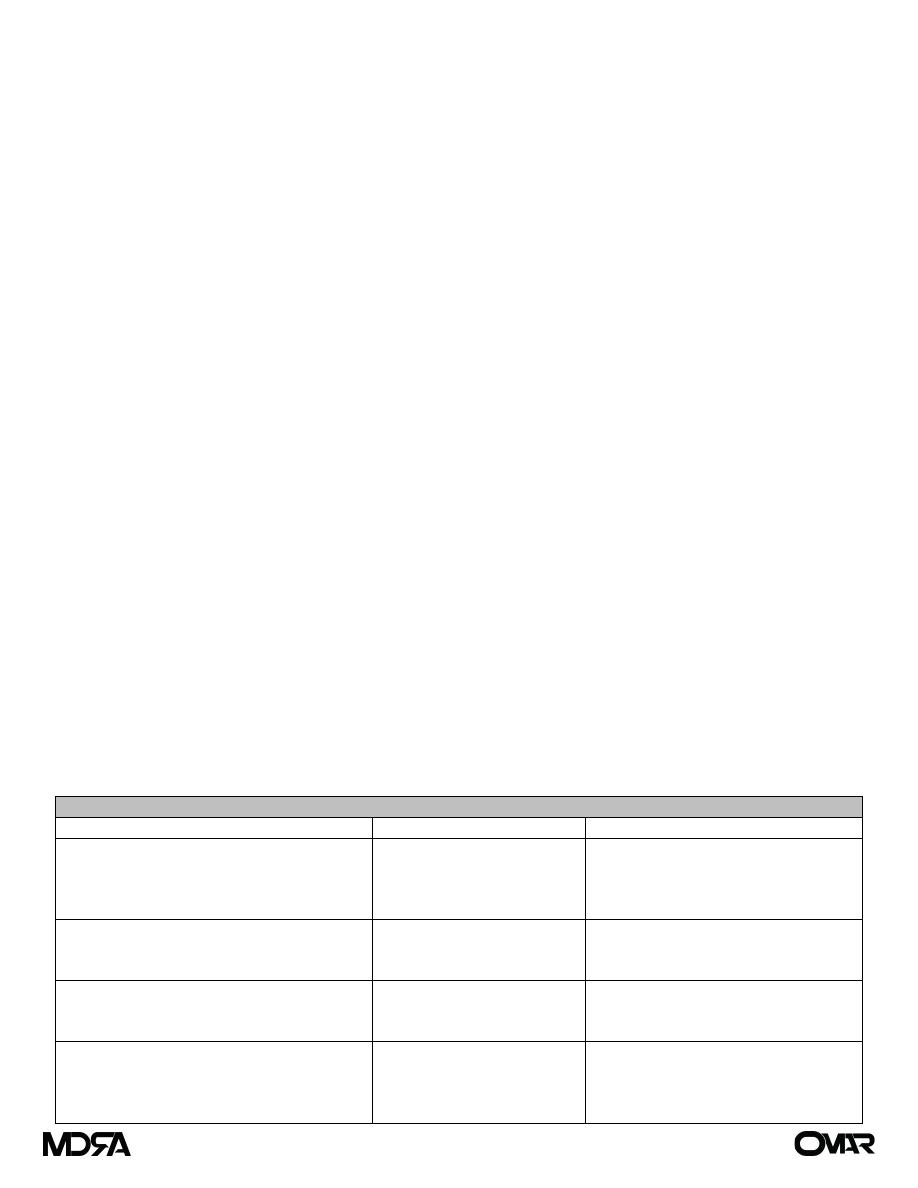

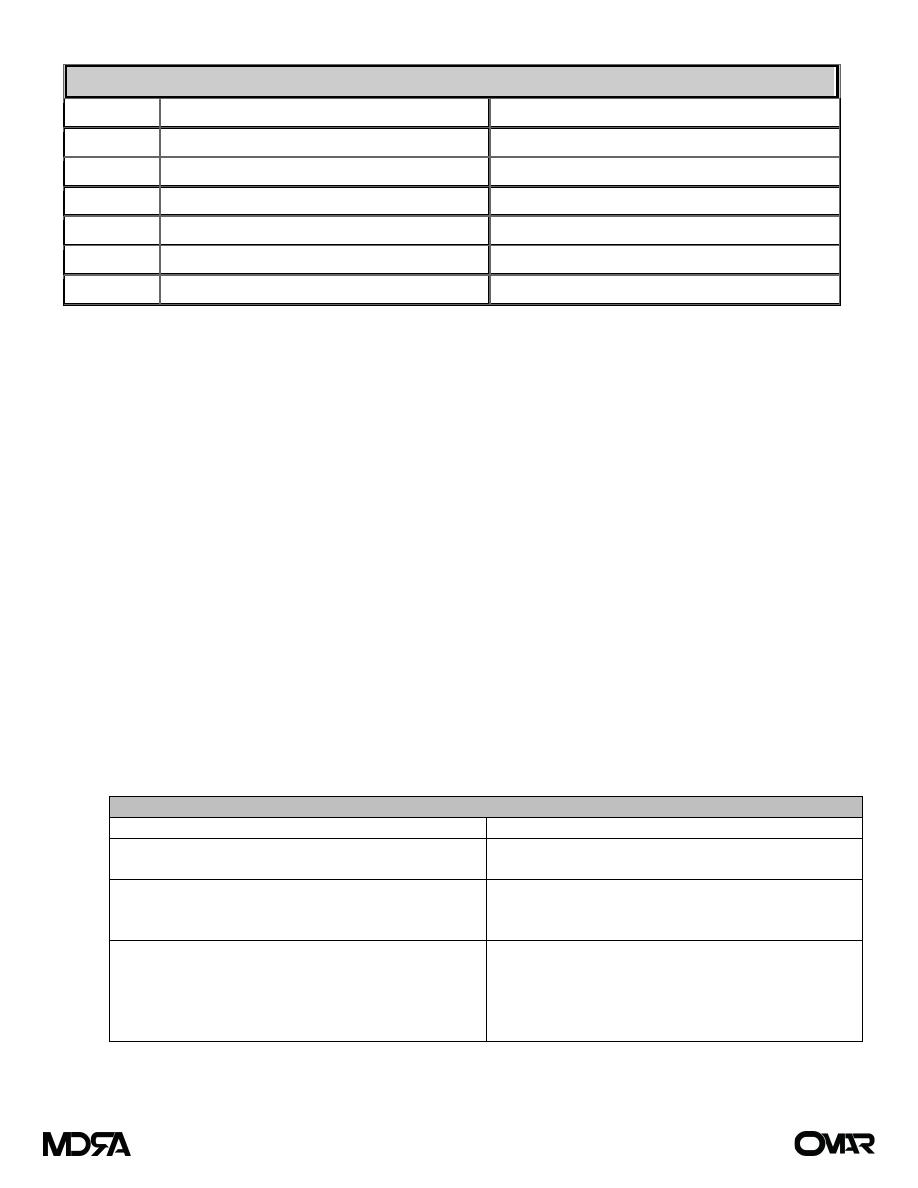

Examples of Inherited syndromes associated with cancer

Syndrome

Gene(s) implicated

Associated tumors

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

APC gene

Colorectal cancer under the age of 25

years, Papillary carcinoma of the

thyroid, Cancer of the ampulla of

Vater, Hepatoblastomas

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

(HNPCC)

DNA mismatch repair genes

(MLH1, MSH2, MSH6)

Colorectal cancer (typically in the 40s

and 50s) Endometrium, stomach,

hepatobiliary

Li–Fraumeni syndrome

p53

Sarcomas, Leukemia, Osteosarcomas

Brain tumors,

Adrenocortical carcinomas

Familial breast cancer

BRCA1, BRCA2

Breast cancer, Ovarian cancer

Papillary serous carcinoma of the

peritoneum

Prostate cancer

Page 2 of 8

Carcinogenesis is the process that results in malignant neoplasm formation. Usually more than one

carcinogen is necessary to produce a tumor, a process which may occur in several steps (Multistep

hypothesis).

Initiators: produce a permanent change in the cells, but do not themselves cause cancer, e.g.

ionizing radiation: this change may be in the form of gene mutation.

Promoters: stimulate clonal proliferation of initiated cells, e.g. dietary factors and hormones: they

are not mutagenic.

Latency: is the time between exposure to carcinogen and clinical recognition of tumor due to:

Time taken for clonal proliferation to produce a significant cell mass.

Time taken for exposure to multiple necessary carcinogens.

Persistence: is when clonal proliferation no longer requires the presence of initiators or promoters

and the tumor cells exhibit autonomous growth.

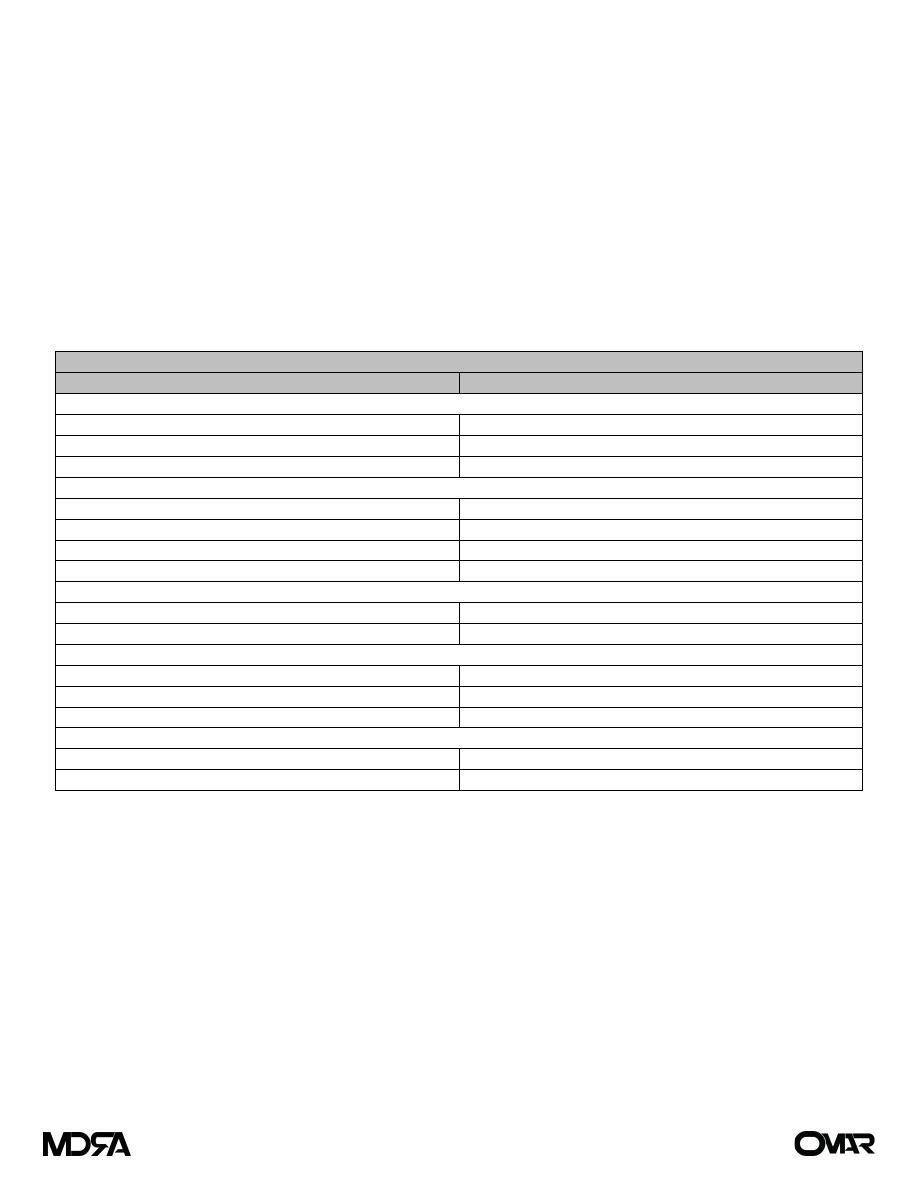

Common carcinogens

Known carcinogen

Type of cancer

Chemicals

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons

Lung cancer (smoking), skin cancers

Aromatic amines

Bladder cancer (rubber and dye workers)

Alkylating agents

Leukemia

Viruses

HIV

Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphoma

Epstein-Barr virus

Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal cancer

Human papilloma virus

Squamous papilloma (wart), cervical cancer

Hepatitis B virus

Liver cell carcinoma

Radiation

UV light

Malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma

Ionizing radiation

Particularly breast, bone, thyroid, marrow

Biological agents

Hormones, e.g. estrogens

Breast and endometrial cancer

Mycotoxins, e.g. aflatoxins

Liver cell carcinoma

Parasites, e.g. schistosoma

Bladder cancer

Miscellaneous

Asbestos

Mesothelioma and lung cancer

Nickel

Nasal and lung cancer

Management of Cancer

The traditional approach to cancer concentrates on diagnosis and active treatment. This is a very limited

view that, once active treatment is complete, there is little more do be done. Prevention is forgotten and

rehabilitation ignored.

Prevention: Cancer prevention can be divided into three categories: (a) primary prevention (i.e.,

prevention of initial cancers in healthy individuals), (b) secondary prevention (i.e., prevention of

cancer in individuals with premalignant conditions), and (c) tertiary prevention (i.e., prevention of

second primary cancers in patients cured of their initial disease).

The systemic or local administration of therapeutic agents to prevent the development of

cancer, called chemoprevention, e.g. Tamoxifin in breast cancer.

Page 3 of 8

In selected circumstances, the risk of cancer is high enough to justify surgical prevention. These

high-risk settings include hereditary cancer syndromes such as hereditary breast-ovarian cancer

syndrome, as well as some nonhereditary conditions such as chronic ulcerative colitis.

Screening

Screening involves the detection of disease in an asymptomatic population in order to improve

outcomes by early diagnosis.

Criteria for screening:

The disease

Recognizable early stage

Treatment at an early stage more effective than at a later stage

Sufficiently common to warrant screening

The test

Sensitive and specific

Acceptable to the screened population

Safe

Inexpensive

The program

Adequate diagnostic facilities for those with a positive test

High-quality treatment for screen-detected disease to minimize morbidity and mortality

Screening repeated at intervals if the disease is of insidious onset

Benefit must outweigh physical and psychological harm

Diagnosis and histopathological classification

Precise diagnosis is crucial to the choice of correct therapy; the wrong operation, no matter how

superbly performed, is useless. An unequivocal diagnosis is the key to an accurate prognosis. Only

rarely can a diagnosis of cancer confidently be made in the absence of tissue for pathological or

cytological examination. Cancer is a disease of cells and, for accurate diagnosis, the abnormal cells

need to be seen, then can be classified according to the following:

Tissue of origin: Organ and tissue type.

Behavior: Benign or malignant.

Primary or secondary.

Grading: is the process of assessing the degree of differentiation of a malignant tumor.

Staging is the process of assessing the extent of local and systemic spread of a malignant tumor or

the identification of features which are risk factors for spread.

The objectives of staging a tumor are:

To plan appropriate treatment (loco-regional and/or systemic) for the individual patient.

To give an estimate of the prognosis.

To compare similar cases when assessing outcomes or designing clinical trials.

The commonest system is the internationally agreed TNM (tumor, nodes, metastases) classification.

The International Union against Cancer (UICC) is responsible for it, and is compatible with, and

relates to, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system for stage grouping of cancer.

Specific staging systems also exist for some tumors (e.g. Duke’s staging in colorectal cancer).

Page 4 of 8

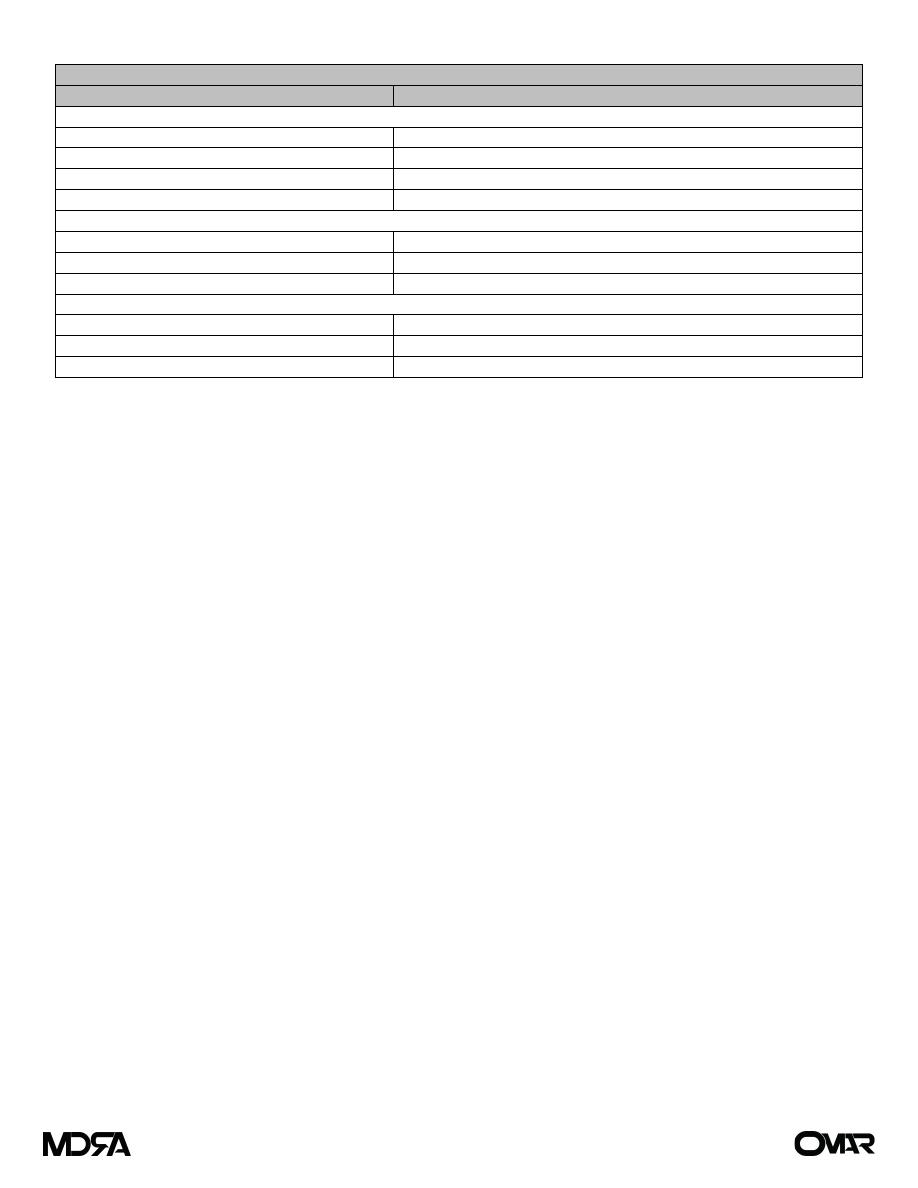

Basic form of TNM classification

Classification

Interpretation

Primary tumor (T)

TX

Primary tumor cannot be evaluated

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Tumor in situ

T1, T2, T3, T4

Size and extent of primary tumor

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated

N0

No regional lymph node involvement

N1, N2, N3

Number and location of involved lymph nodes

Distant metastasis (M)

MX

Distant metastasis cannot be evaluated

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

Tumor markers

Tumor markers are complex molecules, often proteins that can be detected by a variety of techniques,

including chemical, immunological, or bioactivity testing. Most are molecules normally produced by normal

cells in small amounts, but which may be produced in increased amounts by tumor cells due to changes in

cellular function (e.g. increased production, increased gene expression, decreased degradation, increased

release).

Testing

is most commonly via serum measurements or testing tissue specimens.

Common uses include:

Screening (detection of subclinical disease).

Diagnosis (including differentiation of tumor origin in metastatic disease).

Monitoring response to treatment.

Monitoring for development of recurrence.

Non-tumor related elevations in tumor marker levels (reducing the specificity of these tests for tumors)

may occur due to:

Increased production/release due to inflammation, infection, trauma, or surgery.

Decreased removal/destruction due to renal or liver disease.

Common examples include:

AFP (alpha-fetoprotein).

β-HCG (beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin).

CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen).

LDH (lactic dehydrogenase).

PSA (prostate-specific antigen).

Surgical treatment of cancer

For most solid tumors, surgery remains the definitive treatment and the only realistic hope of cure.

However, surgery has several roles in cancer treatment including diagnosis, removal of primary

disease, removal of metastatic disease, palliation, prevention and reconstruction.

Page 5 of 8

Non-surgical treatment of cancer

The principles underlying the non-surgical management of cancer:

First, the spatial distribution of the effects of therapies has to be considered: surgery and

radiotherapy are local or, at best, loco-regional treatments; chemotherapeutic drugs offer a

therapy that is systemic.

Second, the intent underlying the treatment. Occasionally, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or the

combination of the two may be used with curative intent. More usually, chemotherapy or

radiotherapy is used to lower the risk of recurrence after primary treatment with surgery, so-

called adjuvant therapy.

Radiation therapy:

Physical Basis:

Radiation therapy is delivered primarily as high-energy photons (gamma rays and x-rays) and

charged particles (electrons). Gamma rays are photons that are released from the nucleus of a radioactive

atom. X-rays are photons that are created electronically, such as with a clinical linear accelerator. Currently,

high-energy radiation is delivered to tumors primarily with linear accelerators. X-rays traverse the tissue,

depositing the maximum dose beneath the surface, and thus spare the skin. Gamma rays typically are

produced by radioactive sources used in brachytherapy. The dose of radiation absorbed correlates with the

energy of the beam. The basic unit is the amount of energy absorbed per unit of mass (joules per kilogram)

and is known as a gray (Gy). One gray is equivalent to 100 rads, the unit of radiation measurement used in

the past.

Biologic Basis: Until about 20 years ago, it was assumed that the biological effects of radiation

resulted from radiation induced damage to the DNA of dividing cells. Nowadays, it is known that,

although this undoubtedly explains some of the biological effects of radiation, it does not provide a

full explanation. Radiation can, both directly and indirectly, influence gene expression: over 100

radiation-inducible effects on gene expression have now been described. These changes in gene

expression are responsible for a considerable proportion of the biological effects of radiation upon

tumors and normal tissues. In this sense, radiotherapy is a precisely targeted form of gene therapy

for cancer.

Radiation Therapy Planning:

Define the target to treat.

Design the optimal technical set up to provide uniform irradiation of that target.

Choose that schedule of treatment that delivers radiation to that target so as to maximize the

therapeutic ratio. One of the main problems with assessing a therapeutic ratio for a given

schedule of radiation is that there is dissociation between the acute effects on normal tissues

and the late damage. The acute reaction is not a reliable guide to the adverse consequences of

treatment in the longer term.

Page 6 of 8

Effects of Radiation

Organ

Acute Changes (2 to 3 weeks)

Chronic Changes (weeks to years)

Skin

Erythema, wet or dry desquamation, epilation

Telangiectasia, subcutaneous fibrosis, ulceration

GI tract

Nausea, diarrhea, edema, ulceration, hepatitis Stricture, ulceration, perforation, hematochezia

Kidney

—

Nephropathy, renal insufficiency

Bladder

Dysuria

Hematuria, ulceration, perforation

Gonads

Sterility

Atrophy, ovarian failure

Eye

Conjunctivitis

Cataract, keratitis, optic nerve atrophy

Chemotherapy

Cytotoxic drugs kill rapidly-growing cells by damaging their DNA and/or by interfering with DNA synthesis or

cell division.

The relationship between dose and response and the principle of selective toxicity:

Cytotoxic drugs show no intrinsic specificity for cancer cells versus normal tissues: in addition to

killing tumor cells, they damage normal tissues that are rapidly dividing, including the normal bone

marrow, gut lining and hair follicles. An element of selectivity can be introduced by careful

adjustment of dose and schedule to maximize damage to the tumor while allowing recovery of

normal tissues.

Classification of chemotherapeutic drugs:

Chemotherapeutic agents can be classified according to the phase of the cell cycle during which they

are effective. Cell-cycle phase–nonspecific agents (e.g., alkylating agents) have a linear dose-

response curve, such that the fraction of cells killed increases with the dose of the drug. In contrast,

the cell-cycle phase–specific drugs have a plateau with respect to cell killing ability, and cell kill will

not increase with further increases in drug dose.

Chemotherapeutic Agents

Mechanism of action

Examples

Drugs that interfere with mitosis

Vincristine

Taxanes

Drugs that interfere with DNA synthesis

(anti-metabolites)

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)

Methotrexate

6-Mercaptopurine

Drugs that directly damage DNA or

interfere with its function

Mitomycin C

Cisplatinum

Doxorubicin

Cyclophosphamide

Etoposide

Page 7 of 8

Combination Chemotherapy:

To maximize the chance that a tumor will respond to therapy, cytotoxic drugs are often used in

combination. The principles of combination chemotherapy are that the selected drugs should:

Be active against the tumor when used alone.

Have different mechanisms of action, to maximize tumor cell kill.

Have a different spectrum of side-effects, to minimize toxicity to the patient.

Toxicity of Chemotherapy:

The dose of chemotherapeutic drugs is limited by its toxic effects on normal tissues. Some of these

effects are manifest acutely, within minutes to weeks of administration, and may necessitate

adjustment of dose or schedule. Some effects may be delayed for months or years, in some cases

long after completion of the therapy that caused them, that is, when it is too late for dose

modification or cessation of treatment.

Acute toxicity

Extravasation of the drug and tissue damage

Bone marrow toxicity (Sepsis and Bleeding)

Gastrointestinal toxicity

Alopecia

Neuropathy

Long-term toxicity

Cardiotoxicity

Pulmonary toxicity

Carcinogenesis

Gonadal damage

Page 8 of 8