Hip Disorders

DR. JAMAL AL SAIDY

M.B.CH.B…F.I.C.M.S

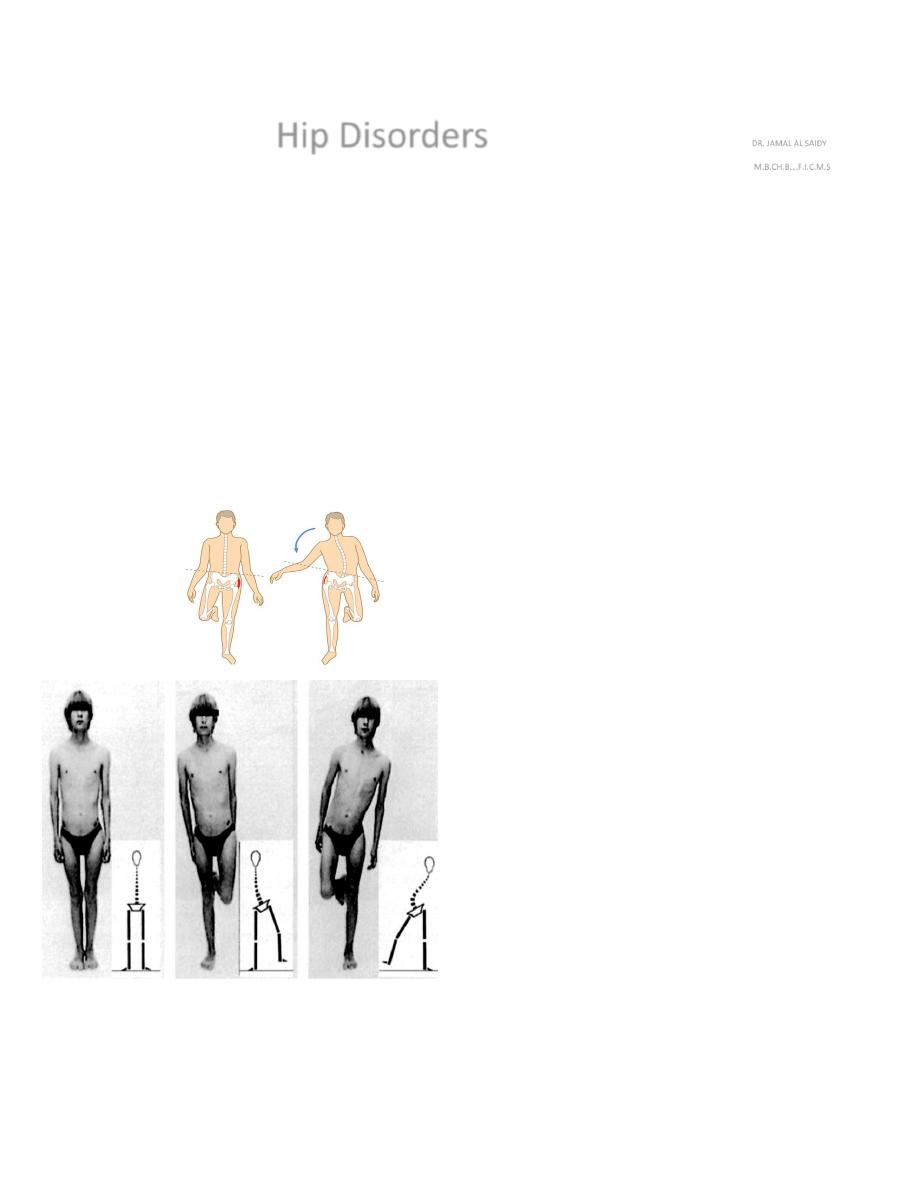

Trendelenburg’s Sign & Test

This is a test for postural stability when the patient stands on one leg. In normal two-legged stance the

body’s centre of gravity is placed midway between the two feet. Normally, in one-legged stance, the pelvis is

pulled up on the unsupported side and the centre of gravity is placed directly over the standing foot If the

weightbearing hip is unstable, the pelvis drops on the unsupported side

side; to avoid falling, the person has

to throw his body towards the loaded side so that the centre of gravity is again over that foot.

In the classical

Trendelenburg test the examiner stands behind the patient and looks at the buttockfolds. Normally in one-

legged stance the buttock on the opposite side rises as the person lifts that leg; in a positive (abnormal) test

the opposite buttock-fold drops.

It is associated with Trendelenburg`s gait.

Causes of a positive Trendelenburg sign are:-

(1) pain on weightbearing

(2) weakness of the hip abductors

(3) shortening of the femoral neck

(4) dislocation or subluxation of the hip.

a b c

Trendelenburg’s sign (a) Standing normally on two legs. (b) Standing on the right leg which has a normal hip whose abductor muscles ensure correct weight transference. (c) Standing

on the left leg whose hip is faulty, and so abduction cannot be achieved; the pelvis drops on the unsupported side and the shoulder swings over to the left.

Developmental Dysplasia Of The Hip (DDH)

The terminology used to describe abnormalities of the paediatric hip.

The term ‘congenital dislocation of the hip’ (CDH) has been largely superseded by developmental dysplasia

of the hip (DDH)

The DDH comprises a spectrum of disorders including acetabular dysplasia without displacement, subluxation

and dislocation and the teratological forms of malarticulation leading to dislocation are also included.

It is dynamic disorder gets worse with growth and better with proper management.

There is a wide geographic variation(1-20 / 1000), uncommon in China & Africa , common in the Middle

East.

Girls : boys

7 : 1, Left hip > right hip & 25 % bilateral.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

……

Not fully understood

o Genetic factors :- play a part in the aetiology, two heritable features which could predispose to hip instability:

generalized joint laxity (a dominant trait), and shallow acetabula (a polygenic trait).

o Hormonal factors:- (e.g. high levels of maternal oestrogen, progesterone and relaxin in the last few weeks of

pregnancy) may aggravate ligamentous laxity in the infant. This could account for the rarity of instability in

premature babies, born before the hormones reach their peak.

o Intrauterine malposition (especially a breech position with extended legs) favours dislocation; Unilateral

dislocation usually affects the left hip; this fits with the usual vertex presentation (left occiput anterior) in which

the left hip is adjacent to the mother’s sacrum, placing it in an adducted position.

Oligohydramnios also

regarded one of intrauterine predisposing factor.

o Postnatal child handling :- may contribute to persistence of neonatal instability and acetabular

maldevelopment, ( e.g. the dislocation is common in those people who swaddle their babies and carry them

with legs together, hips and knees fully extended, and is rare in who carry their babies astride their backs with

legs widely abducted.

Pathology

At birth the hip, though unstable, is probably normal in shape but the capsule is often stretched and

redundant.

During infancy a number of changes develop:-

o primary dysplasia of the acetabulum and/or the proximal femur.

o The cartilaginous socket is shallow and anteverted.

o The cartilaginous femoral head is normal in size but the bony nucleus appears late and

its ossification is delayed throughout infancy.

o The capsule is stretched and the ligamentum teres becomes elongated and hypertrophied.

o Superiorly the acetabular labrum and its capsular edge may be pushed into the socket by the

dislocated femoral head; this fibrocartilaginous limbus may obstruct any attempt at closed reduction

of the femoral head.

After weightbearing, these changes are intensified. Both the acetabulum and the femoral neck remain anteverted and the

pressure of the femoral head induces a false socket to form above the shallow acetabulum. The capsule, squeezed

between the edge of the acetabulum and the psoas muscle, develops an hourglass appearance. In time the surrounding

muscles become adaptively shortened.

Clinical features

Every newborn child should be examined for signs of hip instability. Where there is a family history of congenital instability,

and with breech presentations or signs of other congenital abnormalities.

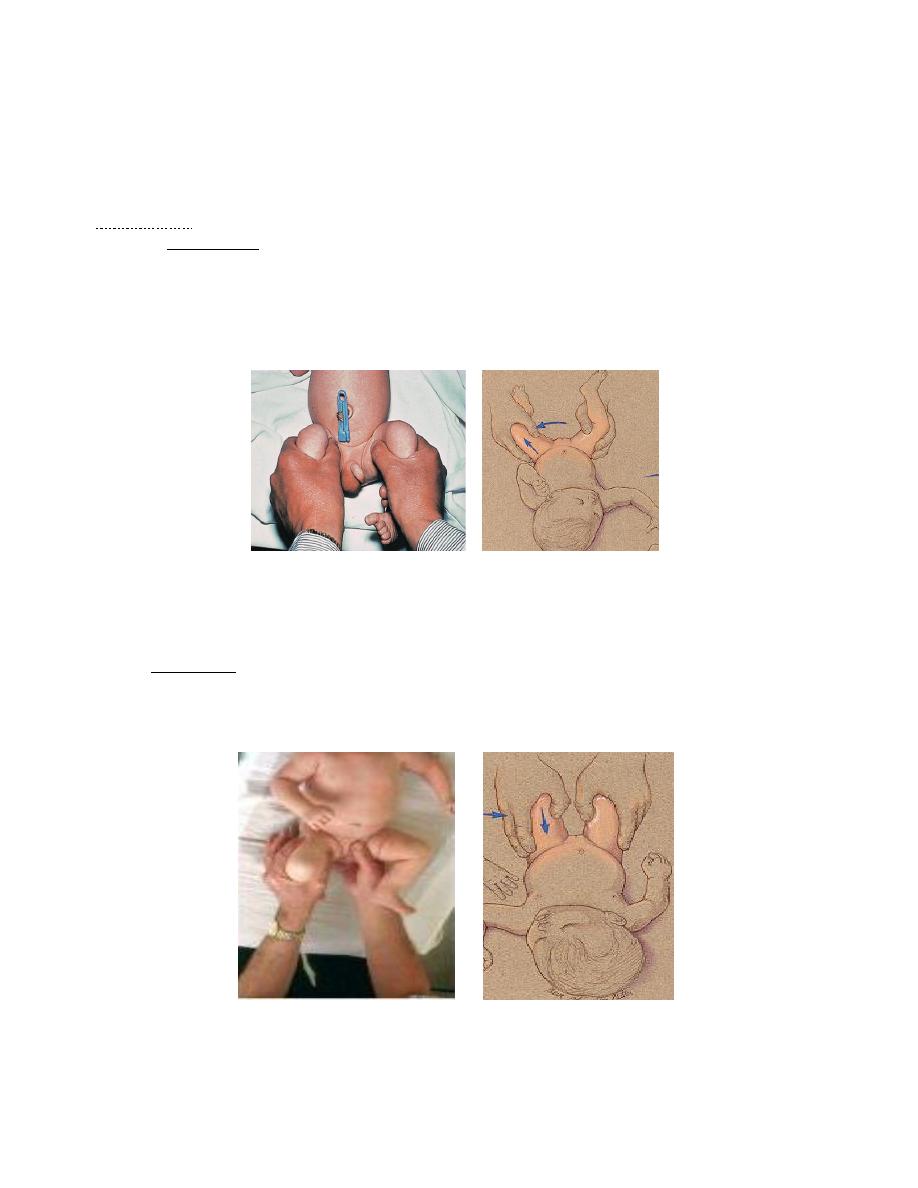

In the neonate

…( Limited abduction : normal 90°)…There are several ways of testing for instability:-

o In Ortolani’s test, the baby’s thighs are held with the thumbs medially and the fingers resting on

the greater trochanters; the hips are flexed to 90 degrees and gently abducted. Normally there is

smooth abduction to almost 90 degrees. In congenital dislocation the movement is usually impeded, but

if pressure is applied to the greater trochanter there is a soft

‘clunk’ as the dislocation reduces, and then the hip abducts

fully (the

‘jerk of entry’). If abduction stops halfway and there is no jerk of entry, there may

be an irreducible dislocation.

Ortolani

’s test.

o Barlow’s test is performed in a similar manner, but here the examiner’s thumb is placed in the groin and,by

grasping the upper thigh, an attempt is made to lever the femoral head in and out of the acetabulum during

abduction and adduction. If the femoral head is normally in the reduced position, but can be made to slip out of the

socket and back in again, the hip is classed as

‘dislocatable’ (i.e. unstable).

Barlow

’s test

After neonatal period & a Late features :-

o difficulty in applying the napkin because of limited abduction, and may observe a clicking hip.

o Asymmetrical creases and the leg is slightly short and externally rotated in unilateral dislocation.

o a thumb in the groin may feel that the femoral head is missing.

o With bilateral dislocation there is an abnormally wide perineal gap.

o Delayed walking by 18 months, the dislocation must be excluded.

o Trendelenburg gait, or a waddling gait.

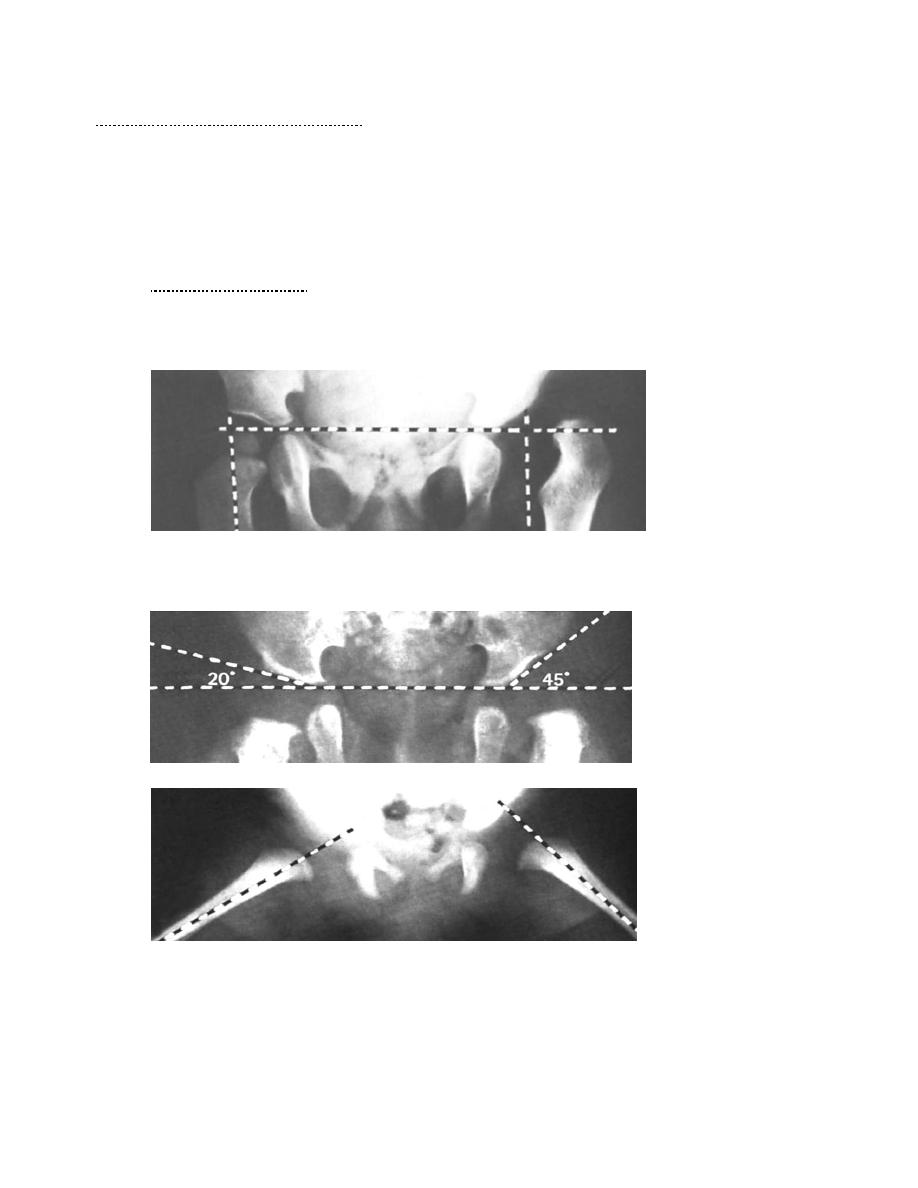

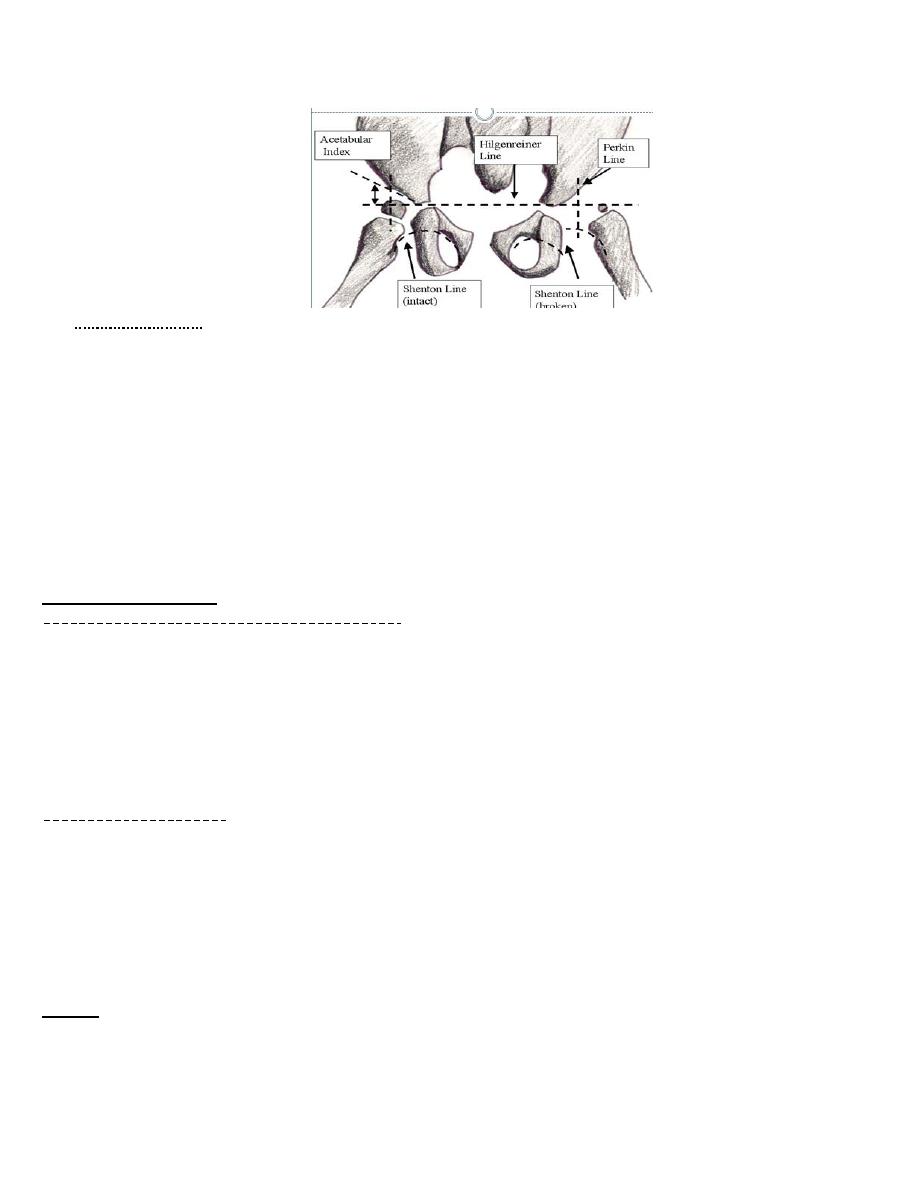

Imaging

o

Plain x-rays X-rays:

of infants are difficult to interpret and in the newborn they can be frankly misleading. This

is because the acetabulum and femoral head are largely (or entirely) cartilaginous and therefore not visible on x-

ray. X-ray examination is more useful after the first 6 months, and assessment is helped by drawing lines on the x-

ray plate to define three geometric indices :

The left hip is dislocated, the femoral head is underdeveloped and the acetabular roof slopes Upwards much more steeply than on the right side. In this case the features

are very obvious but lesser changes can be gauged by geometrical tests. The epiphysis should lie medial to a vertical line which defines the outer edge of the

acetabulum (Perkins

’ line) and below a horizontal line which passes through the triradiate cartilages (Hilgenreiner’s line).

The acetabular roof angle should not exceed 30

°.

Von Rosen

’s lines: with the hips abducted 45° the femoral shafts should point into the

acetabula. In each case the left side is shown to be abnormal.

o Ultrasonography Ultrasound scanning has replaced radiography for imaging hips in the newborn. The

radiographically ‘invisible’ acetabulum and femoral head can, with practice, be displayed with static

and dynamic ultrasound.

Screening

Neonatal screening has led to a marked reduction in missed cases of DDH. Risk factors such as family

history, breech presentation, oligohydramnios and the presence of other congenital abnormalities are

taken into account in selecting newborn infants for special examination and ultrasonography, but

ideally all neonates should be examined.

Management :-

90 % of DDH cases normalize spontaneously in first 6 w

…….

THE FIRST 3

–6 MONTHS

Where facilities for ultrasound scanning are available

:

all newborn infants with a high-risk background or a suggestion of hip instability are examined by

ultrasonography.

If this shows that the hip is reduced and has a normal cartilaginous outline, no treatment is required

but the child is kept under observation for 3–6 months.

In the presence of acetabular dysplasia or hip instability, the hip is splinted in a position of flexion

and abduction (see below) and ultrasound scanning is repeated at intervals until stability and

normal anatomy are restored or a decision is made to abandon in favour of more aggressive

treatment.

If ultrasound is not available

:

the simplest policy is to regard all infants with a high-risk background or a positive Ortolani or

Barlow test, as ‘suspect’ and to nurse them in double napkins or an abduction pillow for the first

6 weeks.

At that stage they are re-examined: those with stable hips are left free but kept under observation

for at least 6 months; those with persistent instability are treated by more formal abduction

splintage (see below) until the hip is stable and x-ray shows that the acetabular roof is developing

satisfactorily (usually 3–6 months).

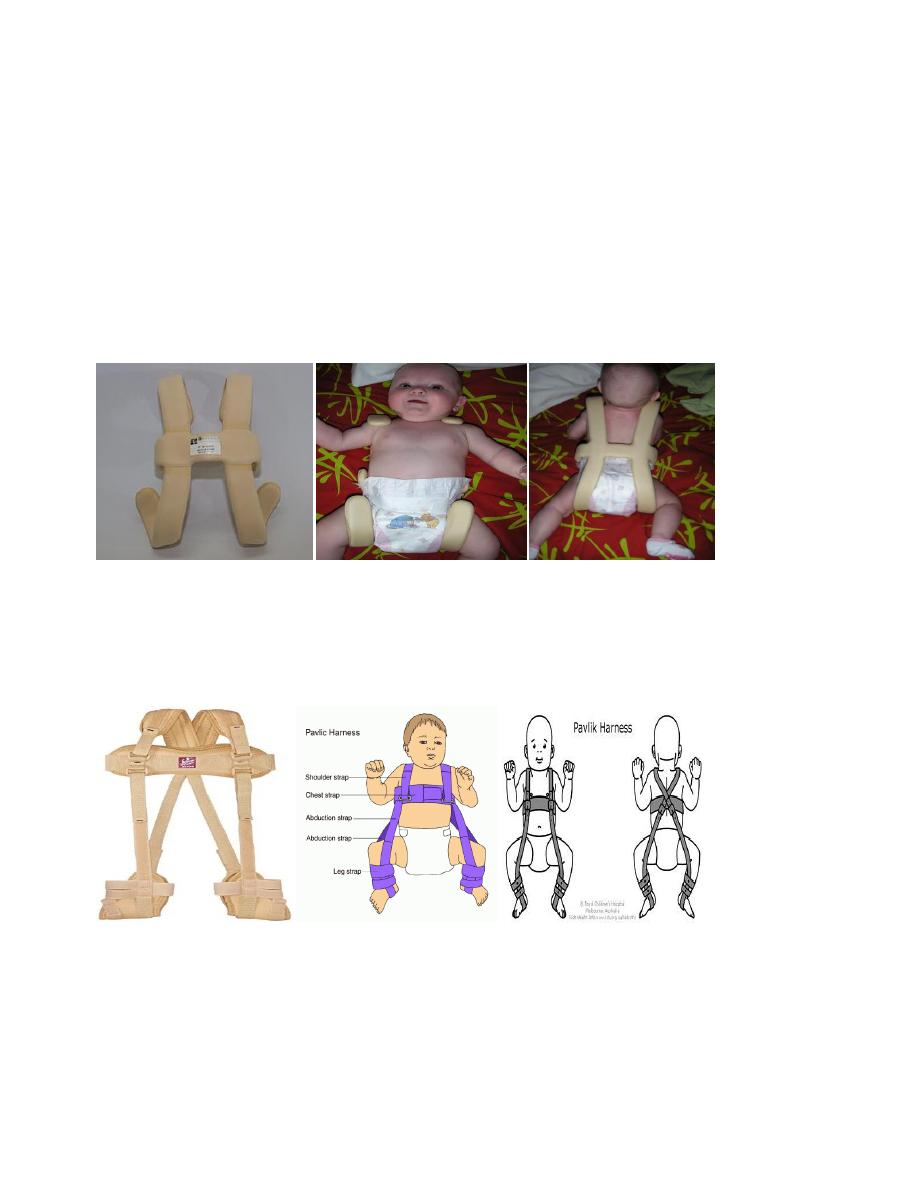

Splintage

:-

The object of splintage is to hold the hips somewhat flexed and abducted.

Von Rosen’s splint is an H-shaped malleable splint that has being easy to apply and easy to take

off.

The Pavlik harness is more difficult to apply but gives the child more freedom while still maintaining

position.

The three golden rules of splintage are:

(1) the hip must be properly reduced before it is splinted.

(2) extreme positions must be avoided.

(3) the hip should be allowed some movement in the splint.

if the hip fails to locate, splintage should be abandoned in favour of closed or operative reduction at

a later date.

Von Rosen’s splint

Pavlik harness Splint

Follow-up : Whatever policy is adopted, follow-up is continued until the child is walking. Sometimes,

even with the most careful treatment, the hip may later show some degree of acetabular dysplasia.

PERSISTENT DISLOCATION: 6

–18 MONTHS

If, after early treatment, the hip is still incompletely reduced, or if the child presents late with a ‘

missed dislocation, the hip must be reduced – preferably by closed methods but if necessary by

operation – and held reduced until acetabular development is satisfactory.

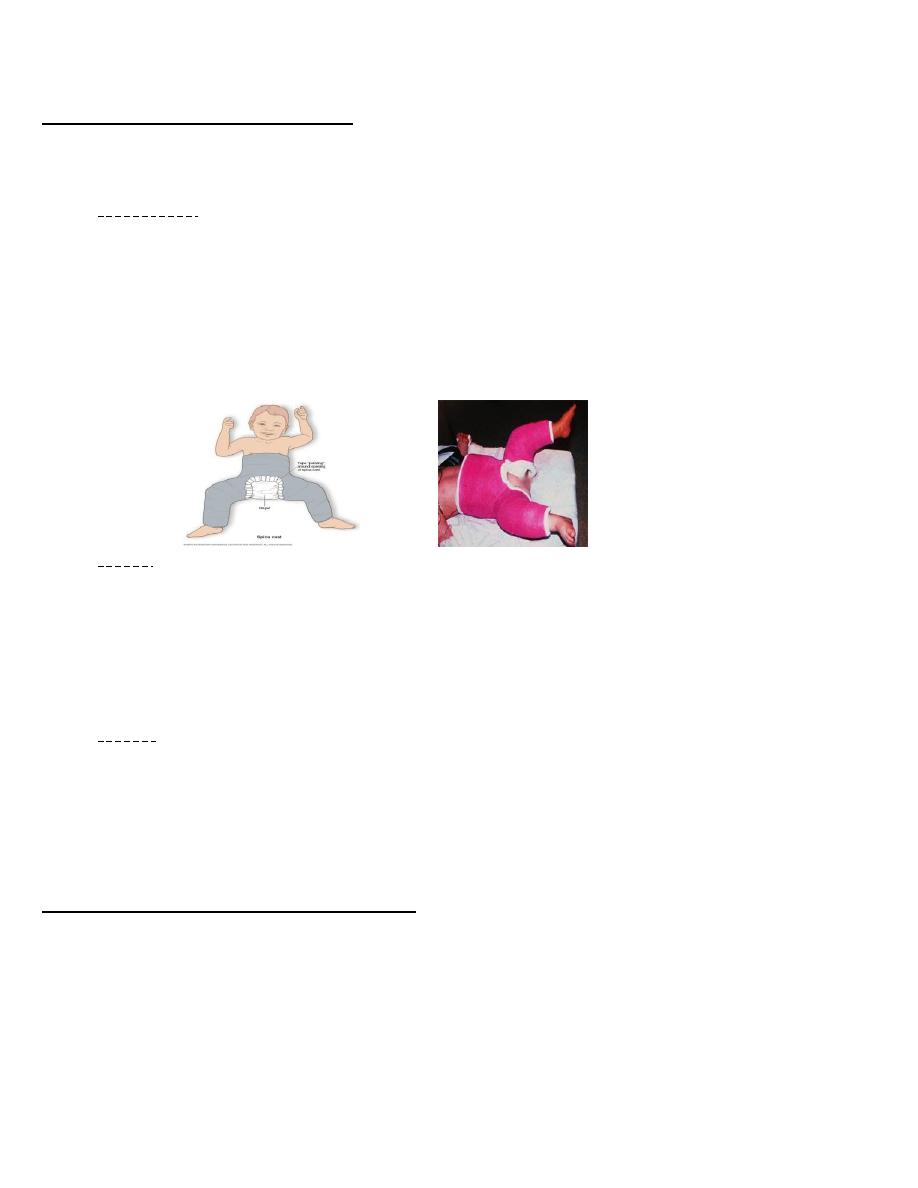

Closed reduction

:

Closed reduction is suitable after the age of 3 months and is performed under general

anaesthesia .

To minimize the risk of avascular necrosis, reduction must be gentle and may be

preceded by gradual traction to both legs.

If this Failed, so operative treatment at approximately 1 year of age.

The hips should be stable in a safe zone of abduction, which may be increased with a

closed adductor tenotomy.

Hip Spica Cast

Splintage

The concentrically reduced hip is held in a plaster spica at 60 degrees of flexion, 40

degrees of abduction and 20 degrees of internal rotation.

After 6 weeks the spica is changed and the stability of the hips assessed .

If the position and stability are satisfactory the spica is retained for a further 6 weeks.

Following plaster removal the hip is either left unsplinted or managed in a removable

abduction splint which is retained for up to 6 months depending on radiological evidence

of satisfactory acetabular development.

Operation

If, at any stage, concentric reduction has not been achieved, open operation is needed.

The psoas tendon is divided; obstructing tissues (redundant capsule and thickened

ligamentum teres) are removed and the hip is reduced.

It is usually stable in 60 degrees of flexion, 40 degrees of abduction and 20 degrees of

internal rotation.

A spica is applied and the hip is splinted as described above.

PERSISTENT DISLOCATION: 18 MONTHS

– 4 YEARS

In the older child, closed reduction is less likely to succeed; many surgeons would proceed straight

to open reduction.

if closed reduction is unsuccessful, a period of traction (if necessary combined with psoas and

adductor tenotomy) may help to loosen the tissues and bring the femoral head down opposite the

acetabulum.

Operation

The joint capsule is opened anteriorly, any redundant capsule is removed along with any

other blocks to reduction including the hypertrophied ligamentum teres and transverse

acetabular ligament and the femoral head is seated in the acetabulum.

Usually a derotation femoral osteotomy held by a plate and screws will be required.

If there is marked acetabular dysplasia, some form of acetabuloplasty will also be needed –

either a pericapsular reconstruction of the acetabular roof (Pemberton’s operation) or an

innominate (Salter) osteotomy which repositions the entire innominate bone and

acetabulum.

Splintage

After operation, the hip is held in a plaster spica for 3 months and then left unsupported to

allow recovery of movement. The child is kept under intermittent clinical and radiological

surveillance until skeletal maturity.

DISLOCATION IN CHILDREN OVER 4 YEARS

Reduction and stabilization become increasingly difficult with advancing age.

in children between 4 and 8 years – especially if the dislocation is unilateral – it is still worth

attempting.

Complications

Failed reduction

Avascular necrosis

Persistent dislocation in adults..........Total joint replacement.

THANK YOU

DR.JAMAL AL-SAIDY

M.B.CH.B..…… F.I.C.M.S