Metabolic response to injury surgery2 dr.ali jaafer

Metabolic response to injury

Classical concepts of homeostasis

Body systems act to maintain internal constancy.

Homeostasis is the foundation of normal physiology

The responses to injury are, in general, beneficial to the host and allow healing/survival.

As a consequence of modern understanding of the metabolic response to injury, elective surgical practice seeks to reduce the need for a homeostatic response by minimising the primary insult (minimal access surgery and ‘stress-free’ perioperative care).

In emergency surgery, where the presence of tissue trauma/sepsis/hypovolaemia often compounds the primary problem, there is a requirement to augment artificially homeostatic responses (resuscitation) and to close the ‘open’ loop by intervening to resolve the primary insult (e.g. surgical treatment of major abdominal sepsis) and provide organ support (critical care) while the patient comes back to a situation in which homeostasis can achieve a return to normality.

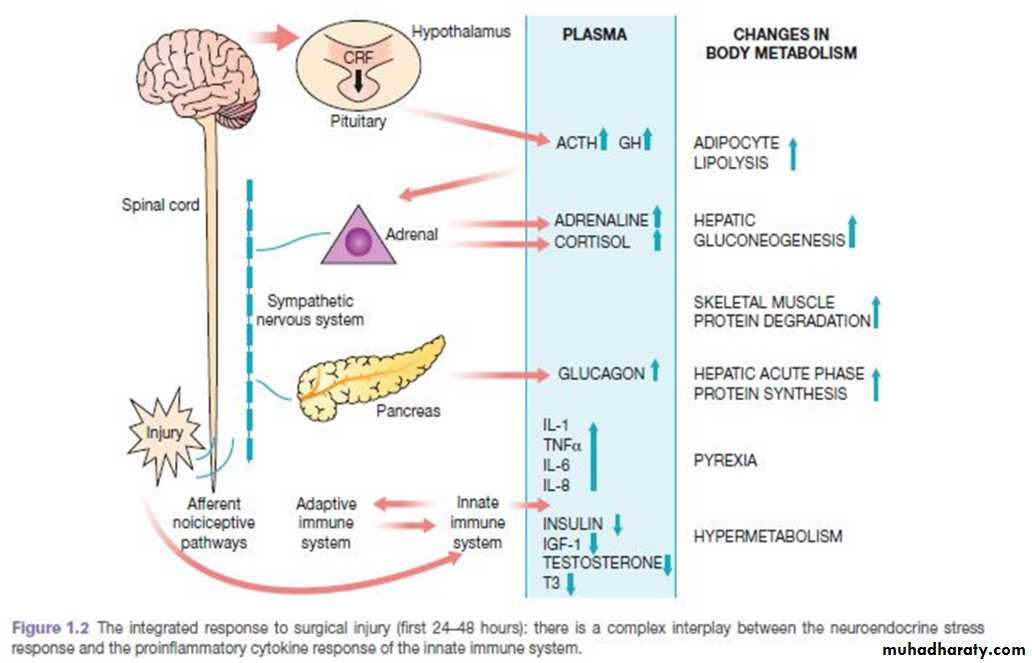

MEDIATORS OF THE METABOLIC RESPONSE TO INJURY

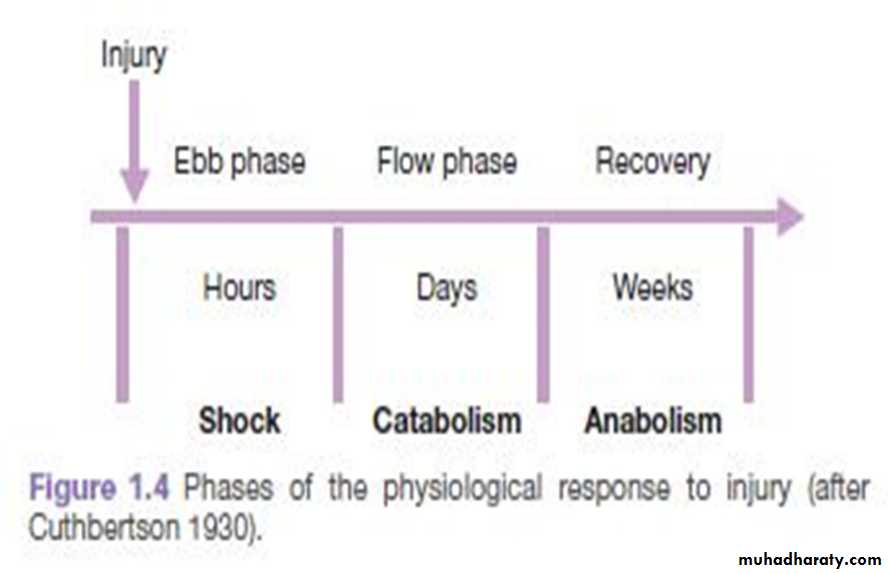

THE METABOLIC STRESS RESPONSE TO SURGERY AND TRAUMA: THE ‘EBB AND FLOW’ MODEL

The ebb phase begins at the time of injury and lasts for approximately 24–48 hours. It may be attenuated by proper resuscitation, but not completely abolished.The ebb phase is characterised by hypovolaemia, decreased basal metabolic rate, reduced cardiac output, hypothermia and lactic acidosis.

The predominant hormones regulating the ebb phase are catecholamines, cortisol and aldosterone

The magnitude of this neuroendocrine response depends on the degree of blood loss and the stimulation of somatic afferent nerves at the site of injury.

The main physiological role of the ebb phase is to conserve both circulating volume and energy stores for recovery and repair.

Hypermetabolic flow phase, which corresponds to SIRS. This phase involves the mobilisation of body energy stores for recovery and repair, and the subsequent replacement of lost or damaged tissue.

It is characterised by tissue oedema (from vasodilatation and increased capillary leakage), increased basal metabolic rate (hypermetabolism), increased cardiac output, raised body

temperature, leukocytosis, increased oxygen consumption and increased gluconeogenesis.

The flow phase may be subdivided into

A. an initial catabolic phase, lasting approximately 3–10 days.

B. an anabolic phase, which may last for weeks

The increased production of insulin at this time is associated with significant insulin resistance and, therefore, injured patients often exhibit poor glycaemic control.

KEY CATABOLIC ELEMENTS OF THE FLOW PHASE OF THE METABOLIC STRESS RESPONSE

Hypermetabolism

The majority of trauma patients demonstrate energy expenditures approximately 15–25% above predicted healthy resting values.

Alterations in skeletal muscle protein metabolism

Under normal circumstances, synthesis equals breakdown and muscle bulk remains constant.

Physiological stimuli that promote net muscle protein accretion include feeding and exercise.

During the catabolic phase of the stress response, muscle wasting occurs as a result of an increase in muscle protein degradation, coupled with a decrease in muscle protein synthesis.

Clinically, a patient with skeletal muscle wasting will experience asthenia, increased fatigue, reduced functional ability, decreased quality of life and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

Alterations in hepatic protein metabolism: the acute phase protein response

Skeletal muscle has a large mass but a low turnover rate (1–2% per day), whereas the liver has a relatively small mass (1.5 kg) but a much higher protein turnover rate (10–20% per day).

The acute phase protein response (APPR) provides proteins important for recovery and repair, but only at the expense of valuable lean tissue and energy reserves.

APPR: increase CRP plasma concentration and decrease albumin plasma concentration.

CHANGES IN BODY COMPOSITION FOLLOWING INJURY

The loss of 1 g of nitrogen in urine is equivalent to the breakdown of 36 g of wet weight lean tissue.

During stress as in starvation there is adaptive changes to attenuate urinary nitrogen loss, thus account for survival of hunger strike for a period of 50-60 days. once loss of body protein mass has reached 30–40% of the total, survival is unlikely.

Critically ill patients admitted to the ICU with severe sepsis or major blunt trauma undergo massive changes in body composition.

Body weight increases immediately on resuscitation with an expansion of extracellular

water by 6–10 litres within 24 hours.

Thereafter,even with optimal metabolic care and nutritional support, total body protein will diminish by 15% in the next 10 days, and body weight will reach negative balance as the expansion of the extracellular space resolves.

It is possible to maintain body weight and nitrogen equilibrium following major elective surgery. This can be achieved by blocking the neuroendocrine stress response with epidural analgesia/other related techniques and providing early oral/enteral feeding.

The early fluid retention phase can be avoided by careful intraoperative management of fluid balance, with avoidance of excessive administration of intravenous saline.

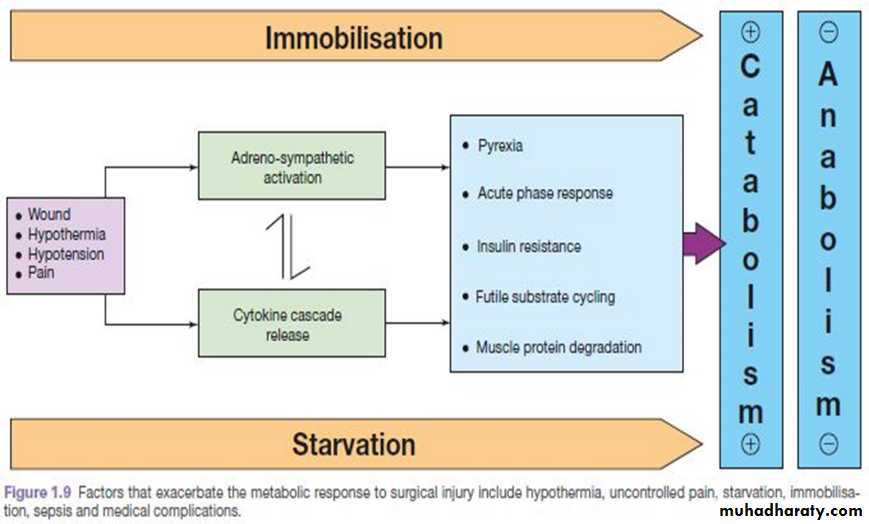

AVOIDABLE FACTORS THAT COMPOUND THE RESPONSE TO INJURY

Volume loss

Careful limitation of intraoperative administration of balanced crystalloids so that there is no net weight gain following elective surgery has been proven to reduce postoperative complications and length of stay.Hypothermia

Hypothermia results in increased elaboration of adrenal steroids and catecholamines. When compared with normothermic controls, even mild hypothermia results in a two- to three-fold increase in postoperative cardiac arrhythmias and increased catabolism.

Maintenance of normothermia by an upper body forced-air heating cover reduces wound infections, cardiac complications and bleeding and transfusion requirements.

Tissue oedema

This can diminish the alveolar diffusion of oxygen and may lead to reduced renal function.Systemic inflammation and tissue underperfusion

Compromisation of microcirculation and subsequent cellular hypoxia contribute to the risk of organ failure.

Starvation

Provision of 2 litres of intravenous 4% dextrose/0.18% sodium chloride as maintenance intravenous fluids for surgical patients who are fasted provides 80 g of glucose per day and has a significant protein-sparing effect.

Avoiding unnecessary fasting in the first instance and early oral/enteral/parenteral nutrition

Modern guidelines on fasting prior to anaesthesia allow intake of clear fluids up to 2 hours before surgery. Administration of a carbohydrate drink at this time reduces perioperative anxiety and thirst and decreases postoperative insulin resistance.

Immobility

Immobility has been recognised as a potent stimulus for inducing muscle wasting.Inactivity impairs the normal meal-derived amino acid stimulation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle.

Avoidance of unnecessary bed rest and active early mobilisation are essential measures to avoid muscle wasting as a consequence of immobility.

A proactive approach to prevent unnecessary aspects

Minimal access techniques

Blockade of afferent painful stimuli (e.g. epidural analgesia, spinal analgesia, wound catheters)

Minimal periods of starvation

Early mobilisation