1

Chemical Composition of Viruses lec2 virology

Viral Protein

The structural proteins of viruses have several important functions.

1- To facilitate transfer of the viral nucleic acid from one host cell to another.

2- To protect the viral genome against inactivation by nucleases.

3- Participate in the attachment of the virus particle to a susceptible cell.

4- Provide the structural symmetry of the virus particle.

5- Determine the antigenic characteristics of the virus

6-Some surface proteins may also exhibit specific activities, eg, influenza virus hemagglutinin

that agglutinates red blood cells.

7- Some viruses carry enzymes (proteins:Trypsin) are essential for the initiation of the viral

replicative cycle

)

influenza virus(

Viral Nucleic Acid

Viruses contain a single kind of nucleic acid either DNA or RNA single or double-stranded,

circular or linear that encodes the genetic information necessary for replication of the virus.

The size of the viral DNA genome ranges from 3.2 kbp (hepadna-viruses) to 375 kbp

(poxviruses). The size of the viral RNA genome ranges from about 7 kb (some picornaviruses

and astro-viruses) to 30 kb (coronaviruses). Viral nucleic acid may be characterized by its G + C

content. DNA viral genomes can be analyzed and compared using restriction endonucleases

(enzymes that cleave DNA at specific nucleotide sequences). Each genome will yield a

characteristic pattern of DNA fragments after cleavage with a particular enzyme.

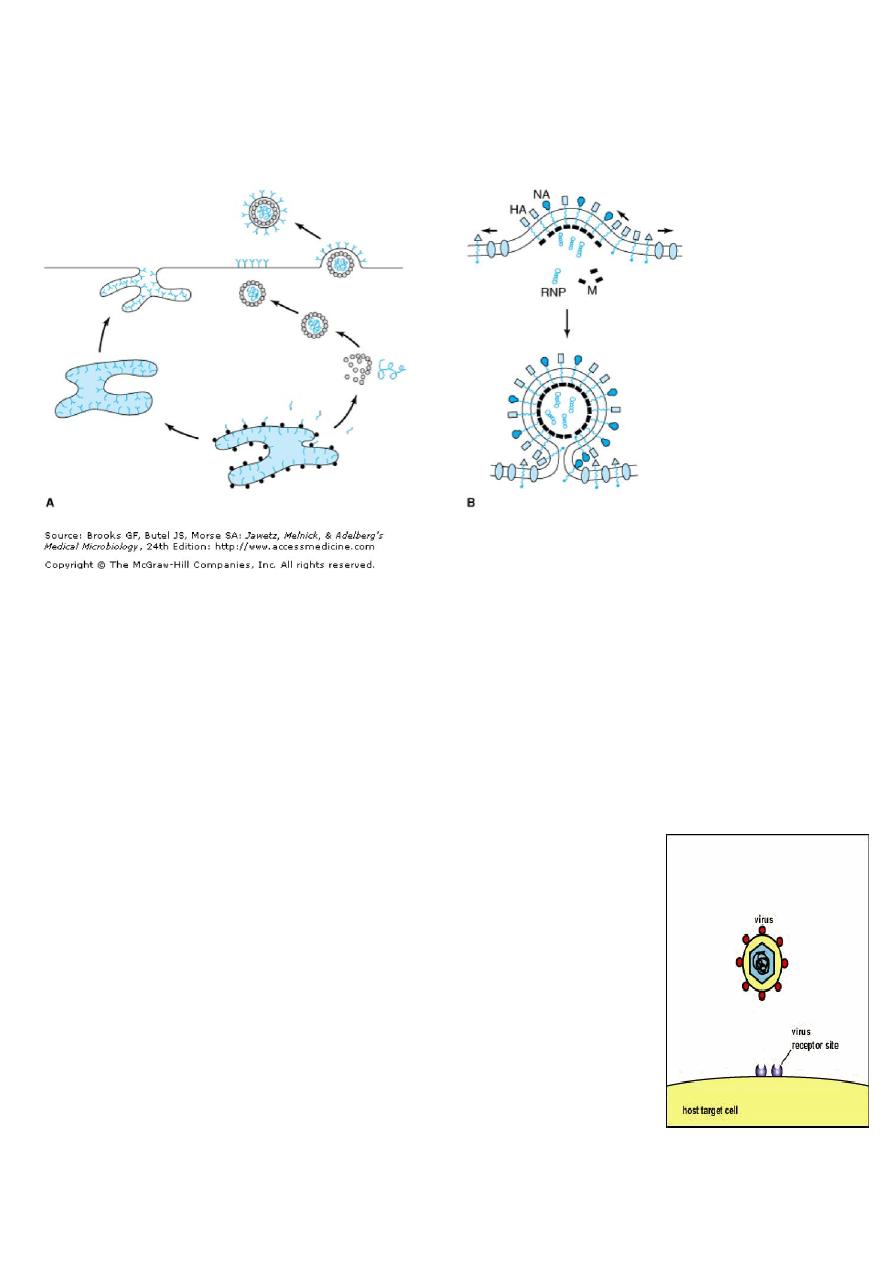

Viral Lipid Envelopes

Some viruses contain lipid envelopes as a part of their structure (eg, Sindbis virus(. The lipid is

acquired when the viral nucleocapsid buds through a cellular membrane in the course of

maturation. Budding occurs only at sites where virus-specific proteins have been inserted into

the host cell membrane. The specific phospholipid composition of a virion envelope is

determined by the specific type of cell membrane involved in the budding process. For

example, herpesviruses bud through the nuclear membrane of the host cell, and the

phospholipid composition of the purified virus reflects the lipids of the nuclear membrane.

2

Lipid-containing viruses are sensitive to treatment with ether and other organic solvents,

indicating that disruption or loss of lipid results in loss of infectivity.

Non-lipid-containing viruses are generally resistant to Ether.

Viral Glycoproteins

Viral envelopes contain glycoproteins. The envelope glycoproteins are virus-encoded.

However, the sugars added to viral glycoproteins often reflect the host cell in which the virus

is grown.

1- It is the surface glycoproteins of an enveloped virus that attach the virus particle to a target

cell by interacting with a cellular receptor.

2- They are also often involved in the membrane fusion step of

infection.

3- The glycoproteins are also important viral antigens.

4- As a result of their position at the outer surface of the virion, they

are frequently involved in the interaction of the virus particle with

neutralizing antibody.

5- Extensive glycosylation of viral surface proteins may prevent

effective neutralization of a virus particle by specific antibody.

3

Cultivation & Assay of Viruses

Cultivation of Viruses

Many viruses can be grown in cell cultures or in fertile eggs under strictly controlled

conditions. Growth of virus in animals is still used for the primary isolation of certain viruses

and for studies of the pathogenesis of viral diseases and of viral oncogenesis.

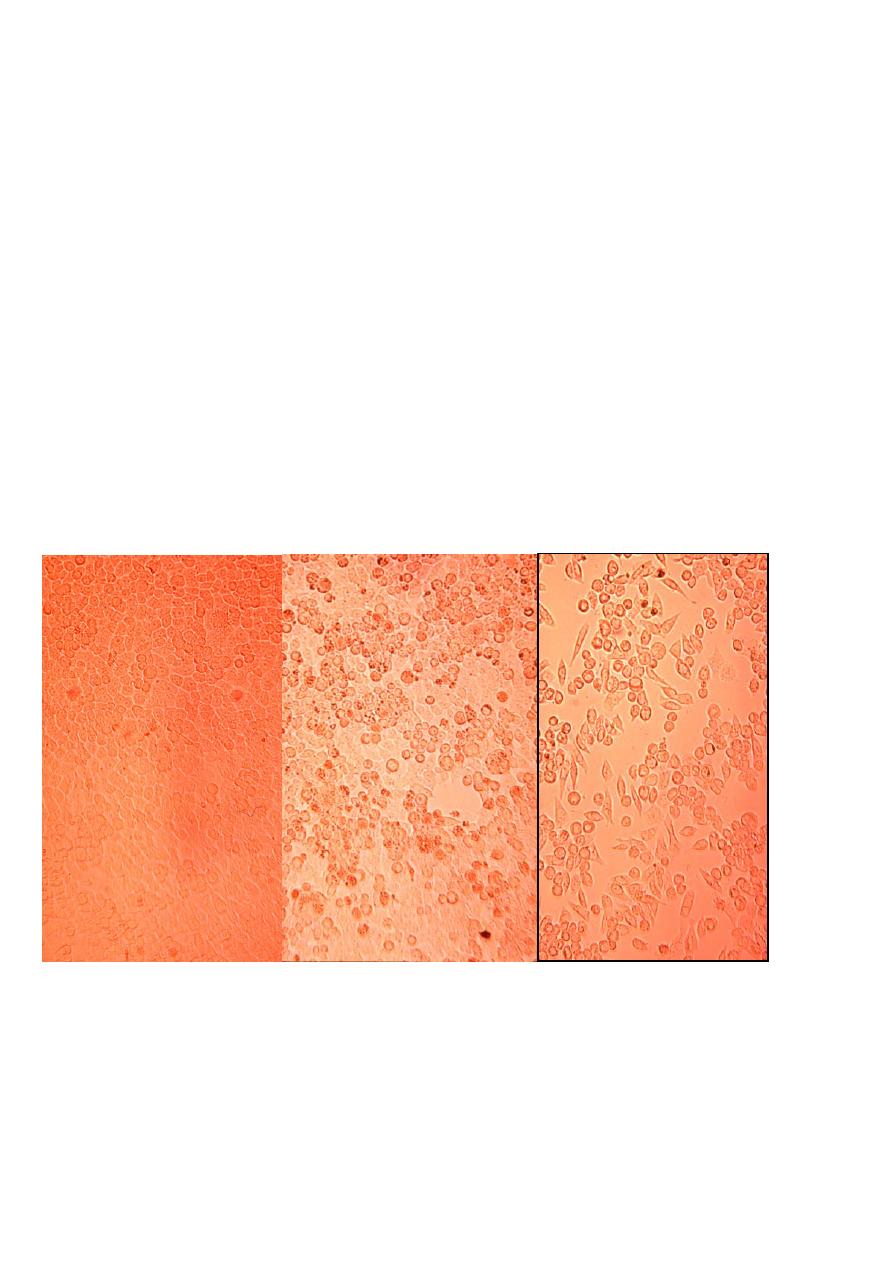

There are three basic types of cell cultures.

Primary cultures are made by dispersing cells (usually with trypsin) from freshly removed host

tissues. In general, they are unable to grow for more than a few passages in culture.

Secondary cultures are diploid cell lines which have undergone a change that allows their

limited culture (up to 50 passages) but which retain their normal chromosome pattern.

Continuous cell lines are cultures capable of more prolonged—perhaps indefinite—growth

that have been derived from diploid cell lines or from malignant tissues. They invariably have

altered and irregular numbers of chromosomes.

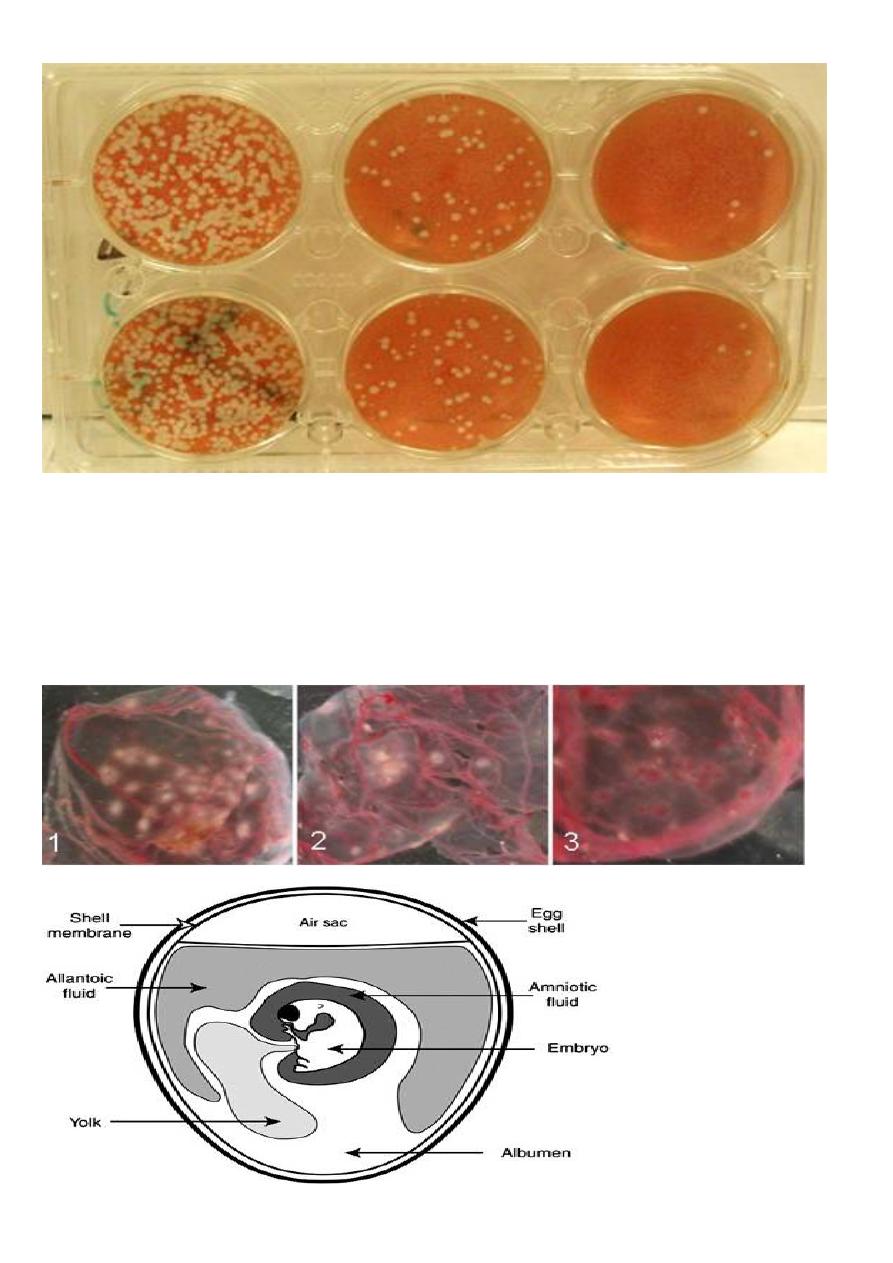

Uninfected early infection late infection

4

Detection of Virus-Infected Cells

Multiplication of a virus can be monitored in a variety of ways:

1. Development of cytopathic effects, include cell lysis or necrosis, inclusion bodies formation,

giant cell formation, and cytoplasmic vacuolization.

2. Appearance of a virus-encoded protein, such as the hemagglutinin of influenza virus.

3. Adsorption of erythrocytes to infected cells, called hemadsorption, due to the presence of

virus-encoded hemagglutinin (parainfluenza, influenza) in cellular membranes.

4. Detection of virus-specific nucleic acid by molecular-based assays such as PCR

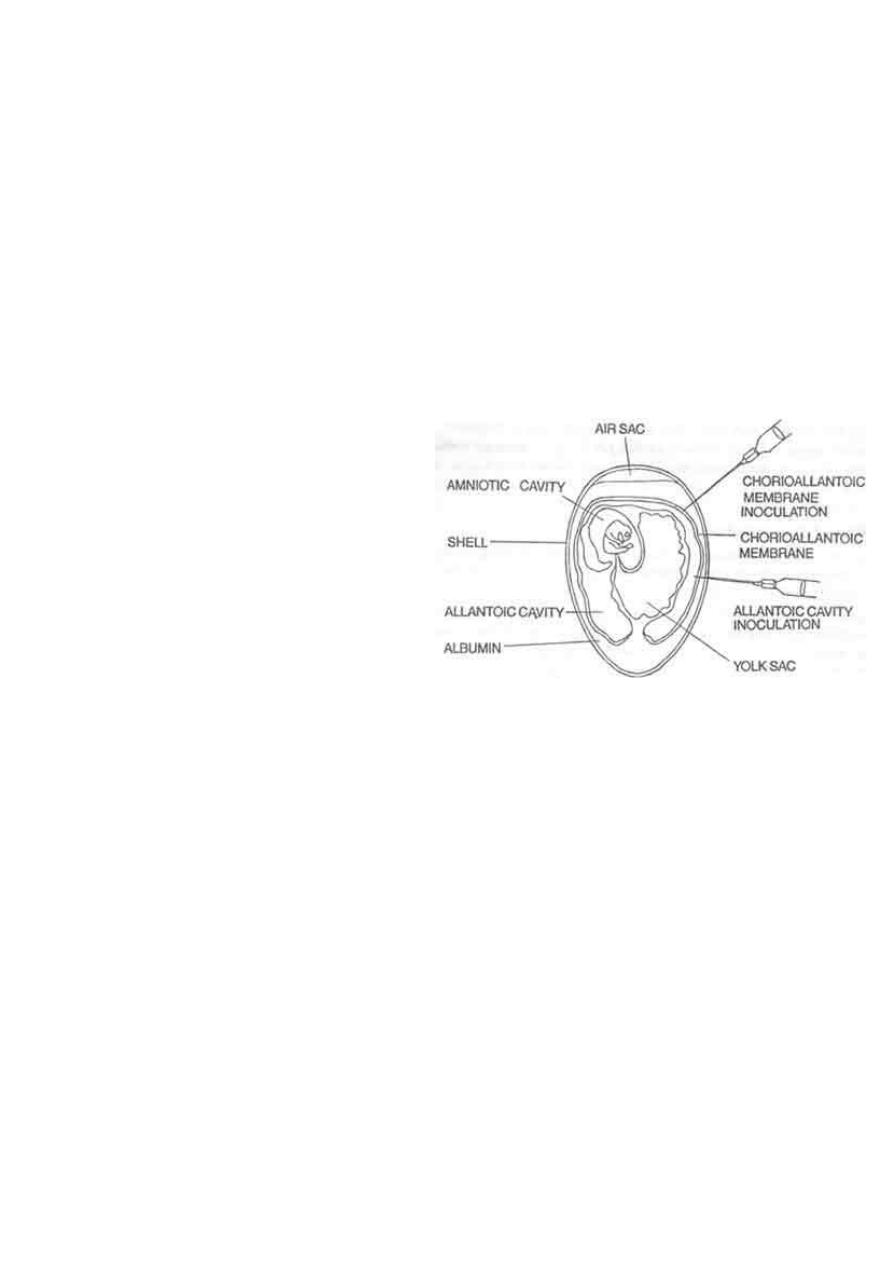

5. Viral growth in an embryonated chick egg

may result in

Death of the embryo (eg, encephalitis

viruses), Production of pocks or plaques on

the chorioallantoic membrane (eg, herpes,

smallpox, vaccinia), Development of

hemagglutinins in the embryonic fluids or

tissues (e.g., influenza).

Inclusion Body Formation

In the course of viral multiplication within cells, virus-specific structures called inclusion bodies

may be produced. They become far larger than the individual virus particle and often have an

affinity for acid dyes (e.g., eosin). They may be situated in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm

(poxvirus), or in both. In many viral infections, the inclusion bodies are the site of

development of the virions (the viral factories).

Variations in appearance of inclusion material depend largely upon the tissue fixative used.

The presence of inclusion bodies may be of considerable diagnostic aid. The intracytoplasmic

inclusion in nerve cells Negri body is pathognomonic for rabies.

5

Quantitation of Viruses

Physical Methods

Quantitative nucleic acid-based assays such as:

1. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can determine the number of viral genome

(infectious and noninfectious) copies in a sample.

2. Serologic tests such as radioimmunoassays (RIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assays (ELISA) can be standardized to quantitate the amount of virus in a sample.

3. Certain viruses contain a protein (hemagglutinin) that has the ability to agglutinate red

blood cells of humans or some animal.

4. Virus particles can be counted directly in the electron microscope by comparison with a

standard suspension of latex particles of similar small size.

Biologic Methods

End point biologic assays depend on the measurement of animal death, animal infection,

or cytopathic effects in tissue culture at a series of dilutions of the virus being tested. The

titer is expressed as the 50% infectious dose (ID50), which is the reciprocal of the dilution

of virus that produces the effect in 50% of the cells or animals inoculated.

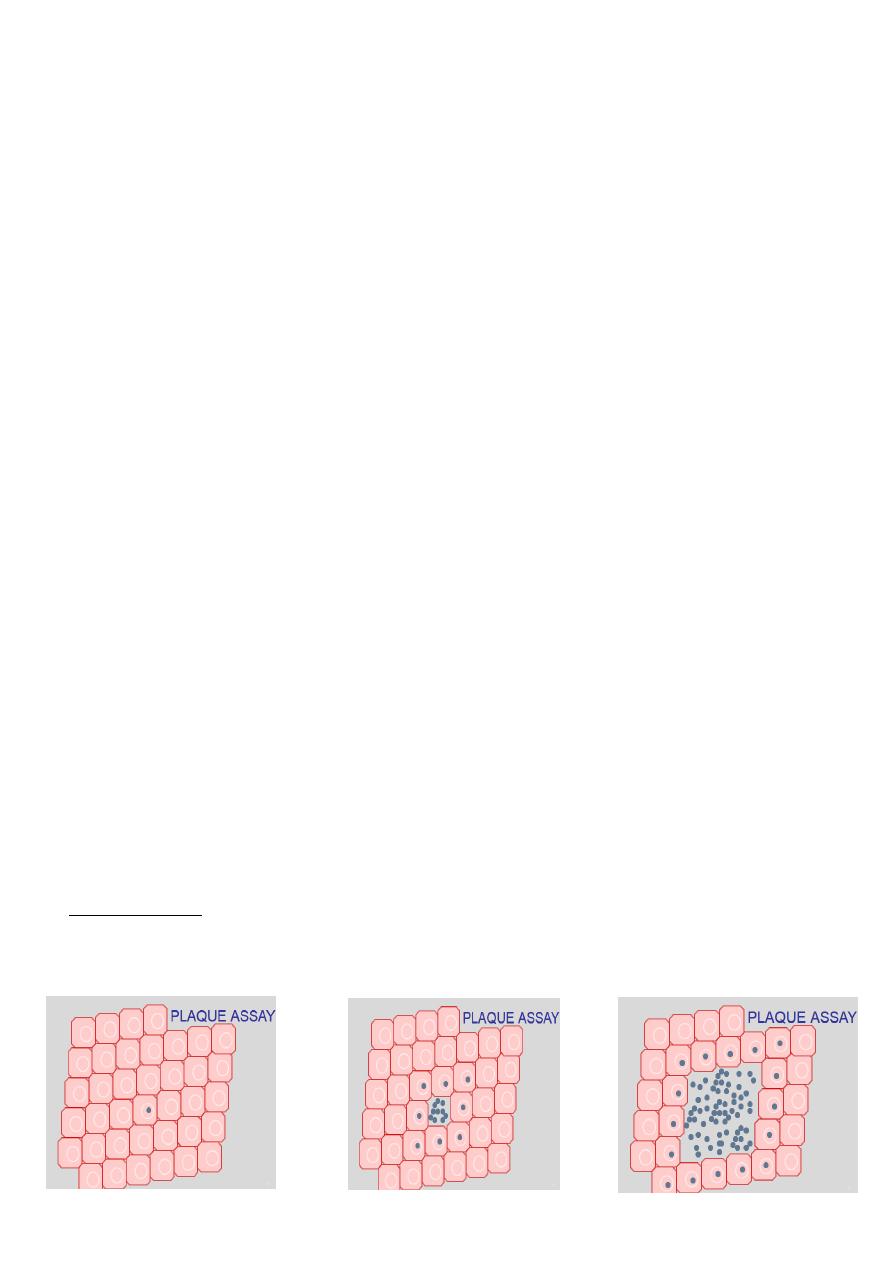

The plaque assay is the most widely used assay for infectious virus. Monolayers of host

cells are inoculated with suitable dilutions of virus and after adsorption are overlaid with

medium containing agar or carboxymethylcellulose to prevent virus spreading throughout

the culture. After several days, the cells initially infected have produced virus that spreads

only to surrounding cells produce a small area of infection, or plaque. Under controlled

conditions, a single plaque can arise from a single infectious virus particle, termed a

plaque-forming unit (PFU) be counted macroscopically.

PLAQUE ASSAY

6

Diluted 10 fold Diluted 100 fold Diluted 1000 fold

Pocks formation: certain viruses, eg, herpes and vaccinia, when inoculated onto the

chorioallantoic membrane of an embryonated egg can be quantitated by relating the number

of pocks counted to the viral dilution inoculated.