Pathogenesis of viruses Micro. Dr. Mohammed

Pathogenesis of viruses

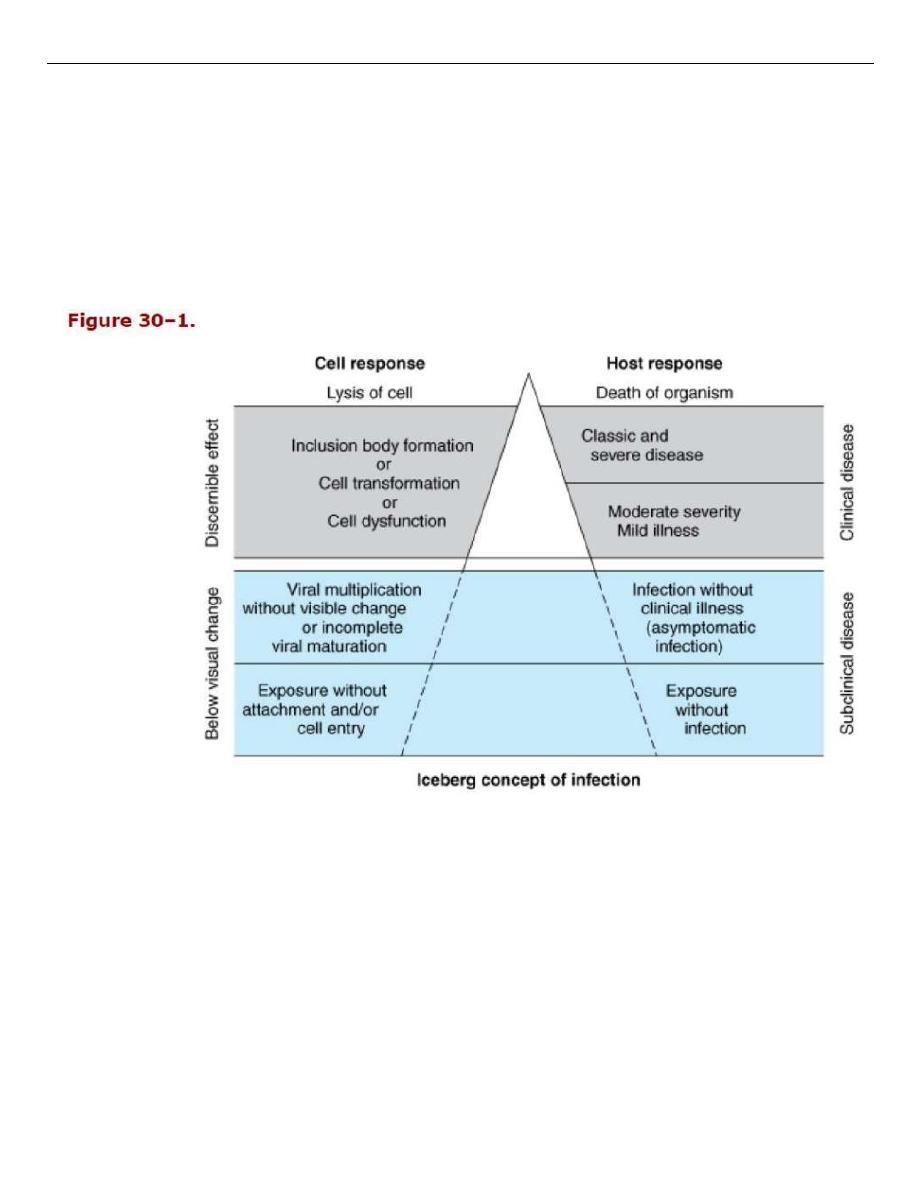

The fundamental process of viral infection is the viral replicative cycle. The cellular response to

that infection may range from no apparent effect to cytopathology with accompanying cell death

to hyperplasia or cancer.

Viral disease is some abnormality that results from viral infection of the host organism. Viral

infections that fail to produce any symptoms in the host are called inapparent (subclinical). In fact,

most viral infections do not result in the production of disease (Figure 30–1).

Important principles that pertain to viral disease include the followings:

(1) Many viral infections are subclinical.

(2) The same disease may be produced by a variety of viruses.

(3) The same virus may produce a variety of diseases.

(4) The outcome in any particular case is determined by both viral and host factors and is

influenced by the genetics of each.

A strain of a certain viruses is more virulent than another strain if it commonly produces more

severe disease in a susceptible host.

Viral virulence in intact animals should not be confused with cytopathogenicity for cultured cells;

viruses highly cytocidal in vitro may be harmless in vivo, and, conversely, noncytocidal viruses may

cause severe disease.

Table 30–1. Important Features of Acute Viral Diseases.

Pathogenesis of Viral Diseases

Steps in Viral Pathogenesis.

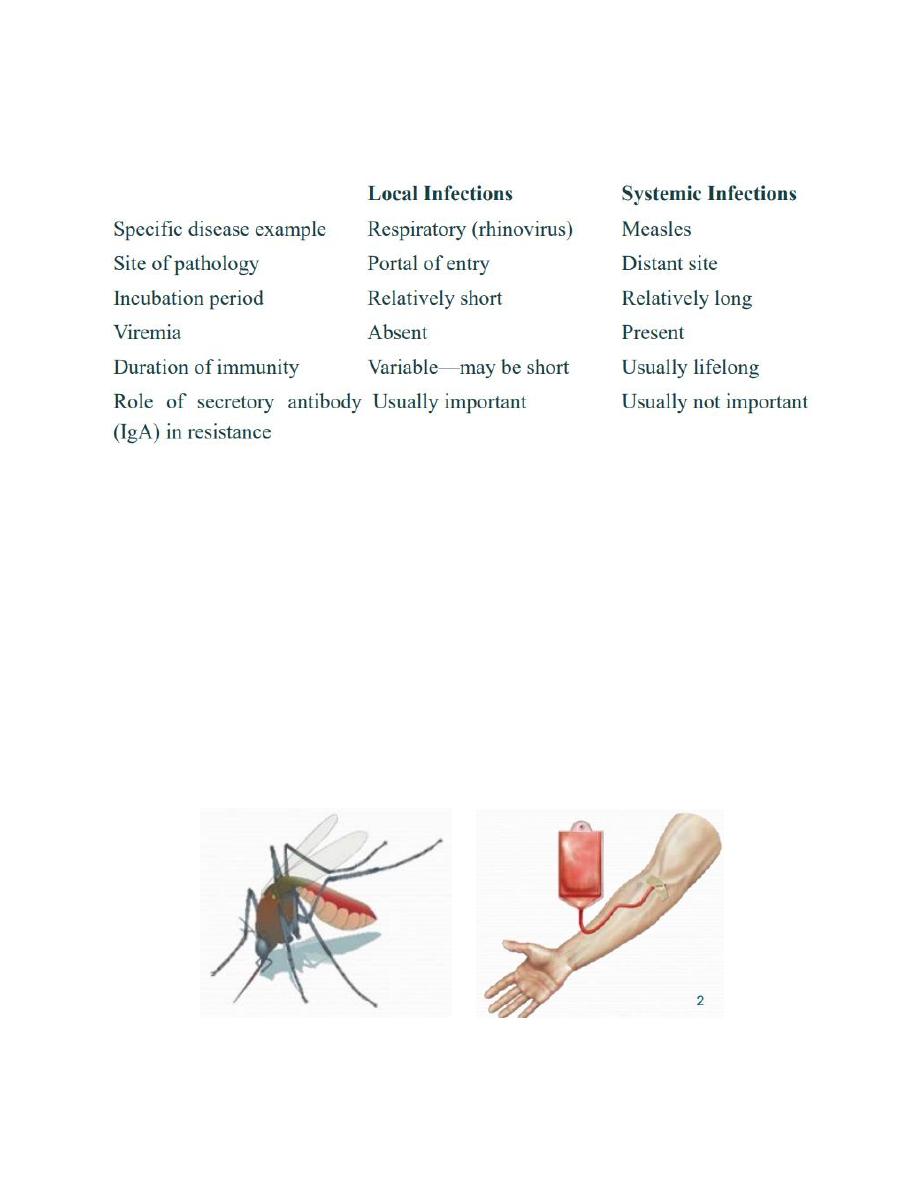

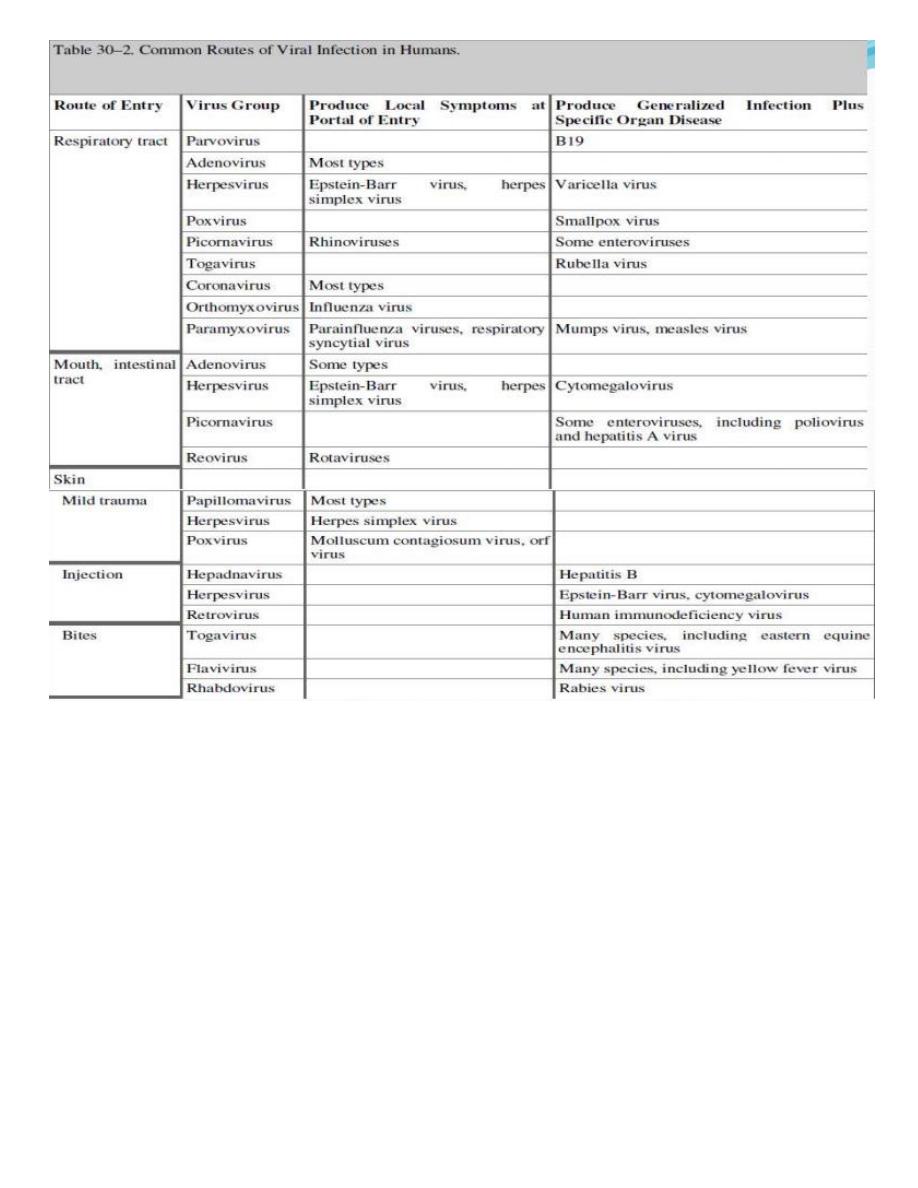

1- Entry and Primary Replication

Virus must first attach to and enter cells of one of the body surfaces (skin, respiratory tract,

gastrointestinal tract, urogenital tract, or conjunctiva). Most viruses enter their hosts through the

mucosa of the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract (Table 30–2). Major exceptions are those viruses

that introduced directly into the blood-stream by needles (hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency

virus [HIV), by blood transfusions, or by insect vectors (arboviruses).

Viruses usually replicate at the primary site of entry. Some, such as influenza viruses (respiratory

infections) and rotaviruses (gastrointestinal infections), produce disease at the portal of entry and

no further systemic spread. They spread locally over the epithelial surfaces, but there is no invasion

of underlying tissues or spread to distant sites.

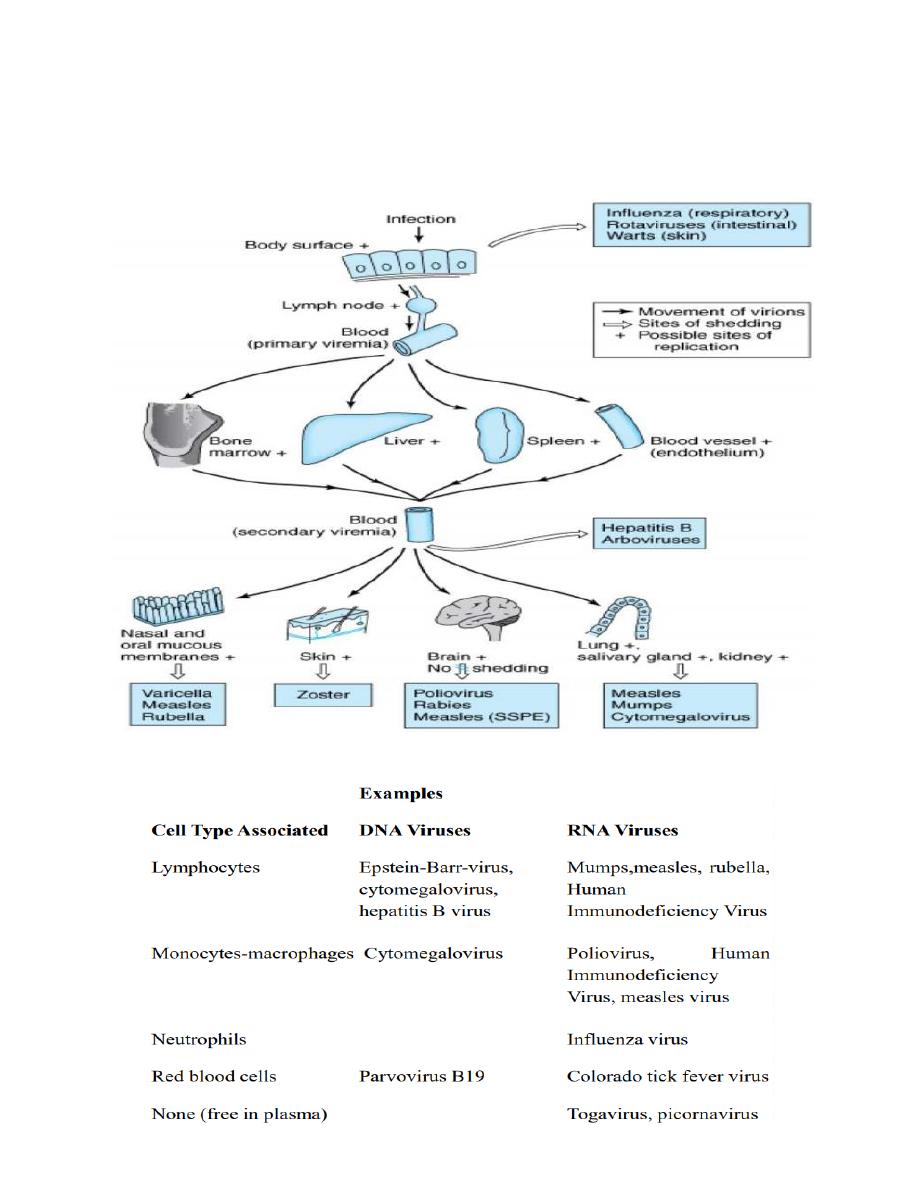

2- Viral Spread and Cell Tropism

Many viruses produce disease at sites distant from their portal of entry (eg, enteroviruses, which

enter through the gastrointestinal tract but may produce central nervous system disease). After

primary replication at the site of entry, these viruses then spread within the host.

Viremia is the presence of virus in the blood. Virions may be free in the plasma (e.g, enteroviruses,

togaviruses) or associated with particular cell types (eg, measles virus) (Table 30–3). The viremic

phase is short in many viral infections. In some instances, neuronal spread is involved; this is

apparently how rabies virus reaches the brain to cause disease and how herpes simplex virus

moves to the ganglia to initiate latent infections.

Viruses tend to exhibit organ and cell specificities. Thus, tropism determines the pattern of

systemic illness produced during a viral infection. As an example, hepatitis B virus has a tropism

for liver hepatocytes, and hepatitis is the primary disease caused by the virus, reflect the presence

of specific cell surface receptors for that virus. Receptors are components of the cell surface with

which a region of the viral surface (capsid or envelope) can specifically interact and initiate

infection.

Factors affecting viral gene expression are important determinants of cell tropism:

1- the polyomavirus enhancer is much more active in glial cells than in other cell types.

2- Proteolytic enzymes: Certain paramyxoviruses are not infectious until an envelope glycoprotein

undergoes proteolytic cleavage.

Multiple rounds of viral replication will not occur in tissues that do not express the appropriate

activating enzymes.

Viral spread may be determined in part by specific viral genes (Reovirus have spread from the

gastrointestinal tract is determined by one of the outer capsid proteins).

3- Cell Injury and Clinical Illness

1- Destruction of virus-infected cells in the target tissues and physiologic alterations produced in

the host by the tissue injury are partly responsible for the development of disease.

2- Some tissues, such as intestinal epithelium, can rapidly regenerate and withstand extensive

damage better than others, such as the brain.

3- Some physiologic effects may result from non-lethal impairment of specialized functions of cells,

such as loss of hormone production.

4- General symptoms associated with many viral infections, such as malaise and anorexia, may

result from host response functions such as cytokine production.

4- Recovery from Infection

The host either succumbs or recovers from viral infection.

Recovery mechanisms include both innate and adaptive immune responses. Interferon and other

cytokines, humoral and cell-mediated immunity, and possibly other host defense factors are

involved.

The relative importance of each component differs with the virus and the disease.

In acute infections, recovery is associated with viral clearance. However, there are times when the

host remains persistently infected with the virus.

5- Virus Shedding

The last stage in pathogenesis is the shedding of infectious

virus into the environment. This is a necessary step to

maintain the viral infection in host populations. Shedding

usually occurs from the body surfaces involved in viral entry.

Shedding occurs at different stages of disease depending on

the particular agent involved.

In some viral infections, such as rabies, humans represent

dead-end infections, and shedding does not occur.

Viral Persistence: Chronic & Latent Virus Infections

Viral infections are usually self-limiting. Sometimes, however, the virus persists for long periods of

time in the host. Longterm virus-host interaction may take several forms.

❖ Chronic infections are those in which replicating virus can be continuously detected, often at

low levels; mild or no clinical symptoms may be evident.

❖ Latent infections are those in which the virus persists in an occult (hidden or cryptic) form most

of times. Viral sequences may be detectable by molecular techniques in tissues harboring latent

infections.

❖ Inapparent or subclinical infections are those that give no overt sign of their presence.

Chronic infections occur with a number of animal viruses, and the persistence in certain instances

depends upon the age of the host when infected. In humans, for example, rubella virus and

cytomegalovirus infections acquired in the uterus characteristically result in viral persistence that

is of limited duration.

Infants infected with hepatitis B virus frequently become persistently infected (chronic carriers);

most carriers are asymptomatic.

In chronic infections with RNA viruses, the viral population often undergoes many genetic and

antigenic changes.

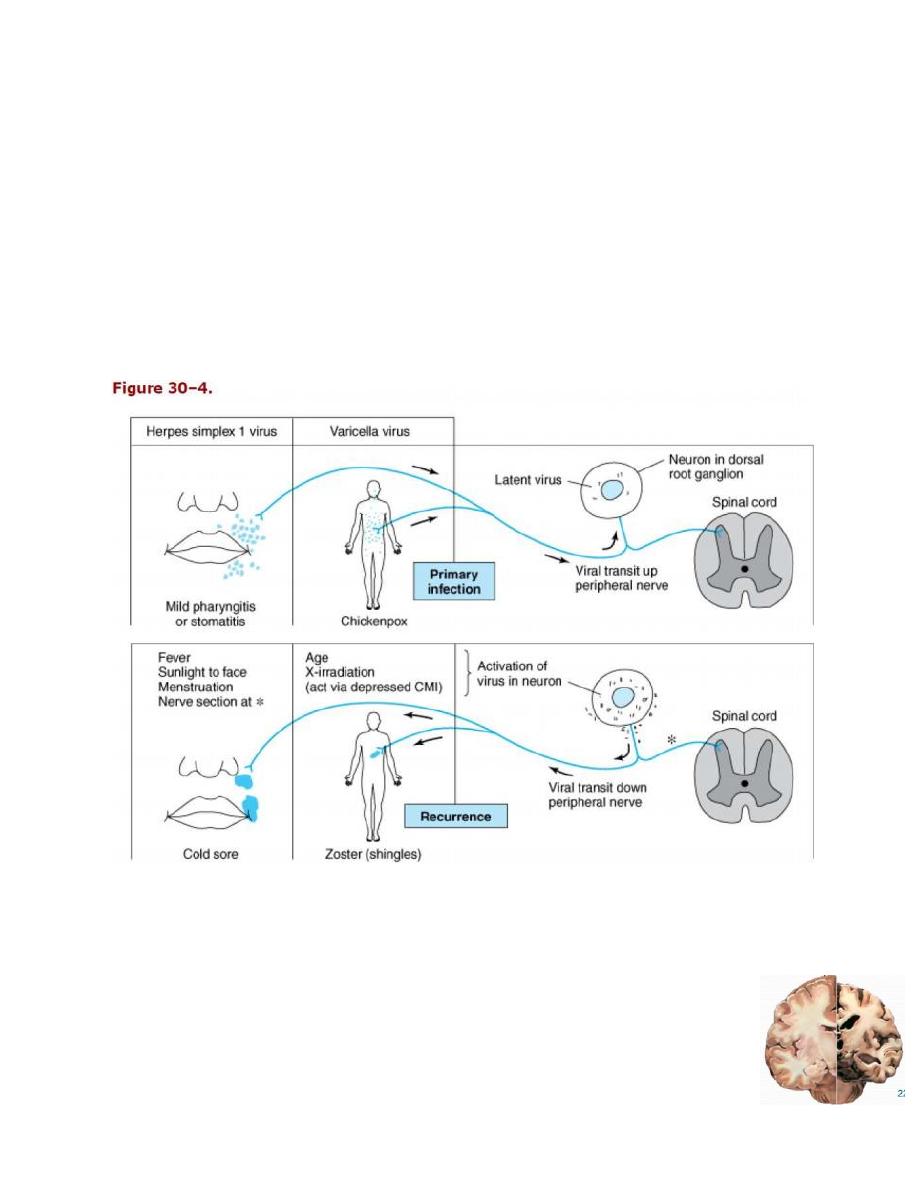

Herpesviruses typically produce latent infections. Herpes simplex viruses enter the sensory ganglia

and persist in a non-infectious state (Figure 30–4). There may be periodic reactivations during

which lesions containing infectious virus appear at peripheral sites (eg, fever blisters).

Chickenpox virus (varicella-zoster) also becomes latent in sensory ganglia. Recurrences are rare

and occur years later, usually following the distribution of a peripheral nerve (shingles).

Other members of herpesvirus family also establish latent infections, including cytomegalovirus

and Epstein-Barr virus.

All may be reactivated by immuno-suppression.

Consequently, reactivated herpesvirus infections may be a serious complication for persons

receiving immunosuppressant therapy.

Persistent viral infections are associated with certain types of cancers in humans as well as with

progressive degenerative diseases of the central nervous system of humans.

Example of different types of persistent viral infections :

Spongiform encephalopathies are a group of chronic, progressive, fatal infections

of the central nervous system caused by unconventional, transmissible agents

called prions. Prions are thought not to be viruses. The best examples of this type

of "slow" infection are scrapie in sheep and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in

cattle; kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease occur in humans.