1

The liver and Gall bladder

Prof.Dr.Maha Shakir LEC1

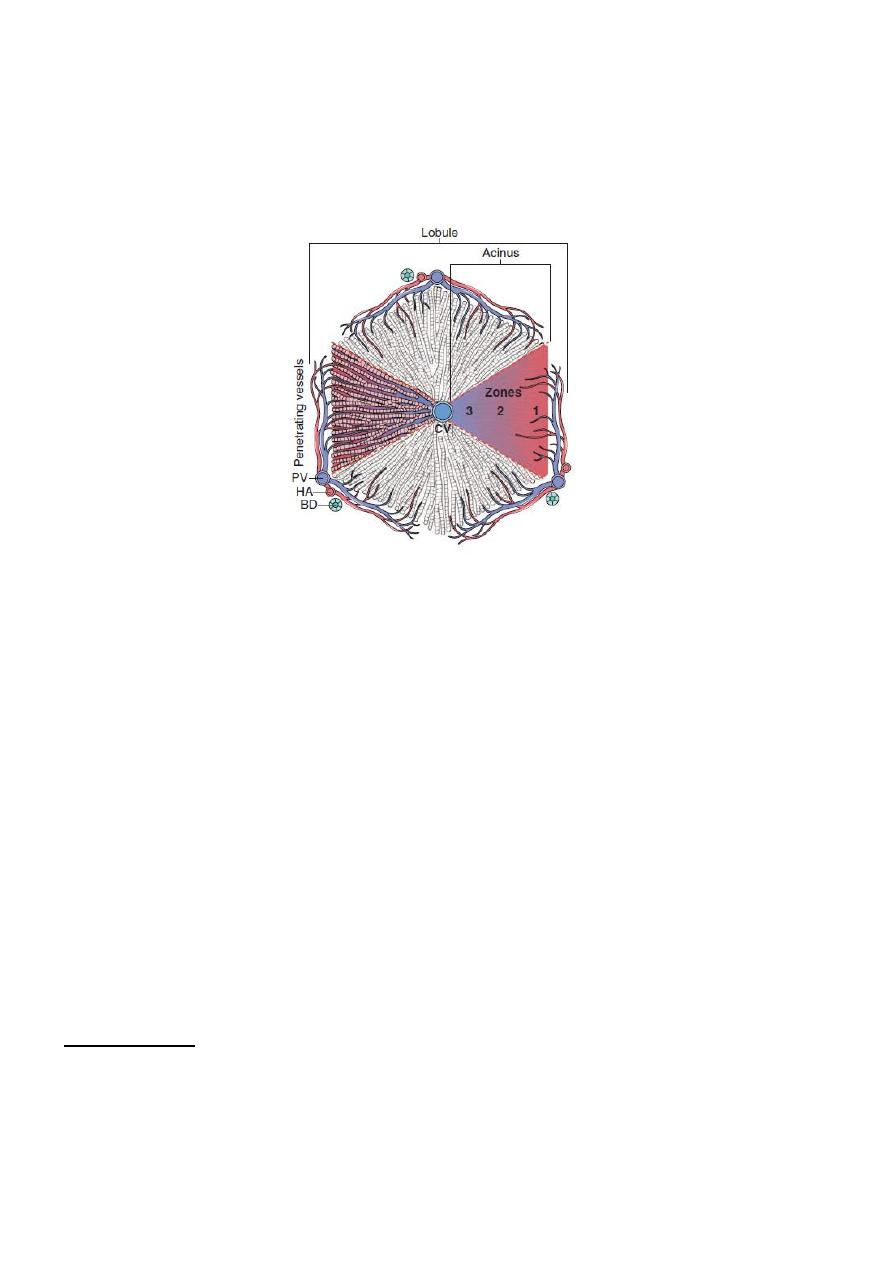

Fig. Models of liver anatomy. In the lobular model, the terminal hepatic vein is at the center of a

“lobule,” while the portal tracts are at the periphery

.

Pathologists often refer to the regions of the

parenchyma as “periportal and centrilobular.” In the acinar model, on the basis of blood flow, three

zones can be defined, zone 1 being the closest to the blood supply and zone 3 being the farthest. BD, Bile

duct; CV, central hepatic vein; HA, hepatic artery.PV, portal tracts.

Liver Failure

The most severe clinical consequence of liver disease is liver failure. It primarily

occurs in three clinical scenarios:acute, chronic, and acute-on-chronic liver failure.

Acute Liver Failure

Acute liver failure is defined as a liver disease that produces hepatic encephalopathy

within 6 months of the initial diagnosis. The condition is known as fulminant liver

failure when the encephalopathy develops within 2 weeks of the onset of jaundice,

and as subfulminant liver failure›when the encephalopathy develops within 3 months.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis

:-mean any

inflammatory lesion of the liver. This term is not used for

local lesions such as an abscess but only when there is diffuse involvement of the

liver.

There are many etiological factors that causing hepatitis such as alcoholic hepatitis,

drug induce hepatitis and viral hepatitis.

Viral hepatitis:- mean infection of the hepatocytes by virus that produces necrosis

and inflammation of the liver and presented with jaundice. It caused mainly by

hepatotropic viruses( which are hepatitis virus A,B,C,D,E,G).

Hepatitis viruses C &B are the most common cause of chronic hepatitis, liver

cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

2

Clinicopathologic Syndromes of Viral Hepatitis

infection with hepatitis viruses produces a wide range of outcomes. Acute infection

by each of the hepatotropic viruses may be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

HAV and HEV do not cause chronic hepatitis, and only a small number of HBV-

infected adults develop chronic hepatitis. In contrast, HCV is notorious for producing

chronic infections.

Fulminant hepatitis is unusual and is seen primarily with HAV, HBV, or HDV

infections.

Although HBV and HCV are responsible for most cases of chronic hepatitis, there are

many other causes of similar clinicopathologic presentations, including autoimmune

hepatitis and drug- and toxin-induced hepatitis.

Acute viral hepatitis:-

Whichever virus is involved, acute disease follows a similar

course, consisting of:

(1) an incubation period of variable length

(2) a symptomatic preicteric phase;

(3) a symptomatic icteric phase;

(4) convalescence.

Peak infectivity occurs during the last asymptomatic days of the incubation period

and the early days of acute symptoms.

Pathological Features ot acute hepatitis

:-

Grossly, normal or slightly mottled. At the other end of the spectrum,massive hepatic

necrosis may produce a greatly shrunken liver.

Microscopically,

1. mononuclear cells predominate in all phases of viral hepatitis.

Portal inflammation in acute hepatitis is minimal or absent.

2. hepatocyte injury may result in necrosis or apoptosis. In severe acute hepatitis,

confluent necrosis of hepatocytes is

seen around central veins.

3. With increasing severity, there is central portal bridging necrosis, followed by

parenchymal collapse.

4. In its most severe form, massive hepatic necrosis and fulminant liver failure

ensue.

Chronic Hepatitis:-

The defining histologic feature of chronic viral hepatitis is mononuclear portal

infiltration.

It may be mild to severe and variable from one portal tract to the other.

There is lobular hepatitis.

The hallmark of progressive chronic liver damage is scarring.

At first, only portal tracts exhibit fibrosis, but in some patients, with time, fibrous

septa—bands of dense scar—will extend between portal tracts. In the most severe

cases, continued scarring and nodule formation leads to the development of cirrhosis.

3

Certain histologic features point to specific viral etiologies in chronic hepatitis. In

chronic hepatitis B, “ground-glass” hepatocytes (cells with endoplasmic reticulum

swollen by HBsAg) are a diagnostic hallmark, and the presence of viral antigen in

these cells can be confirmed by immunostaining.

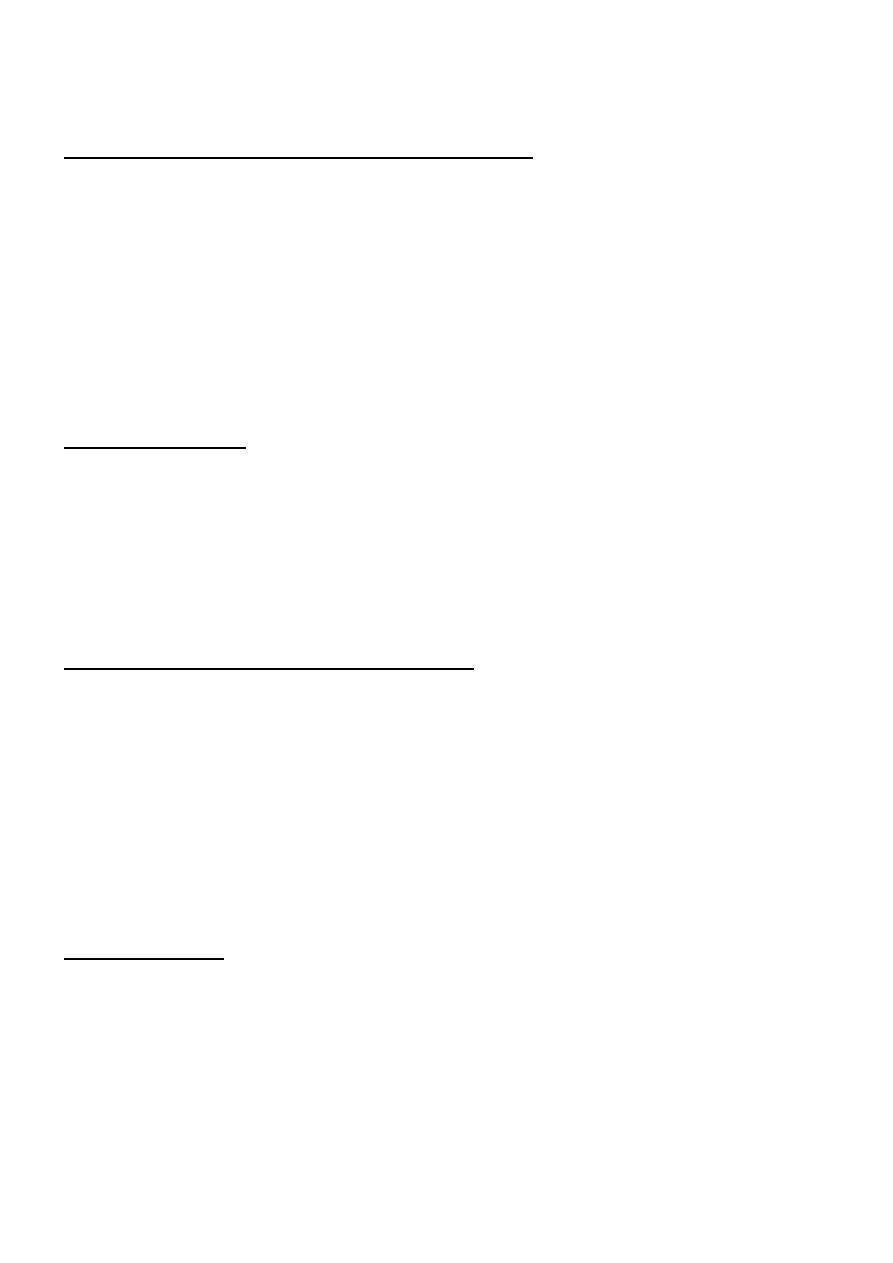

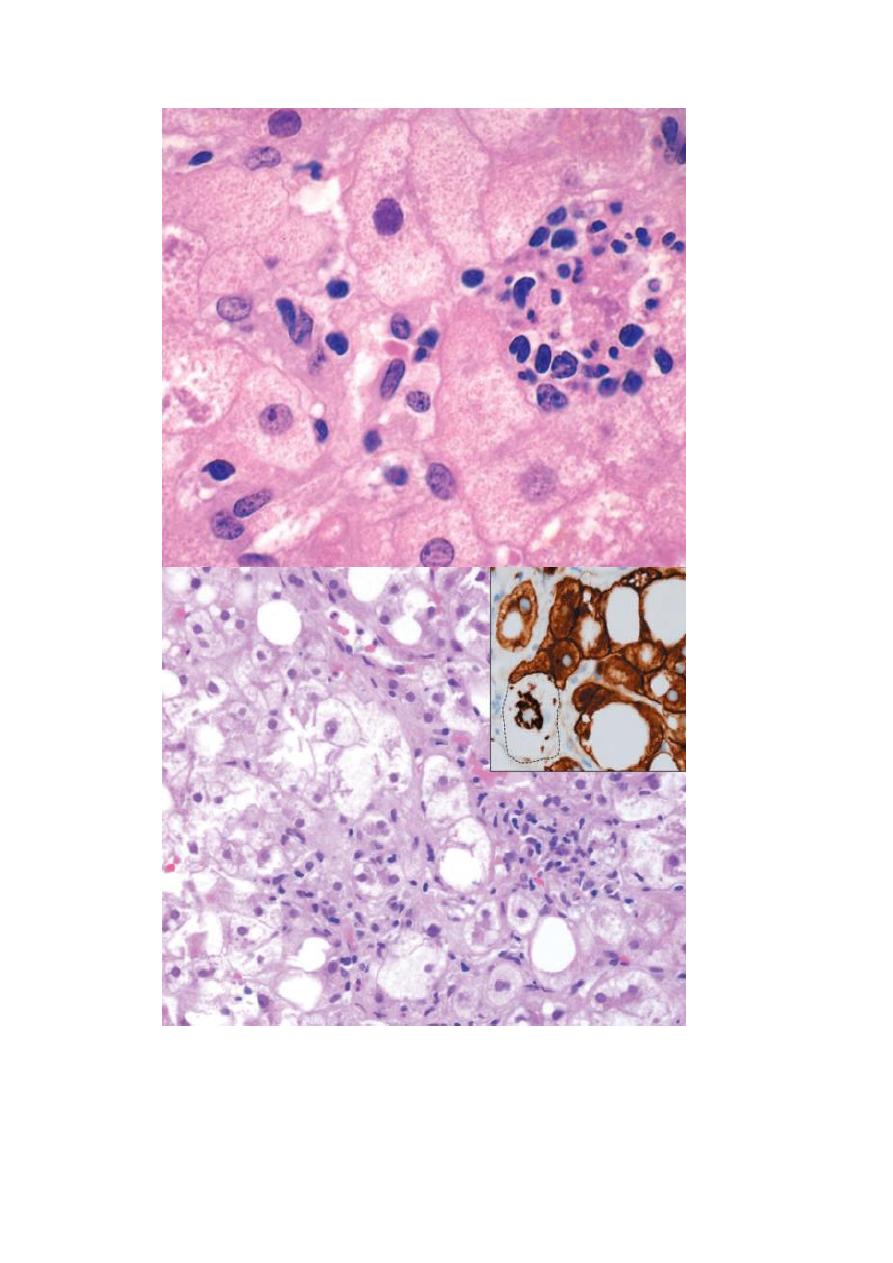

Fig. Morphologic features of acute and chronic hepatitis. There is very little portal mononuclear infiltration in acute

hepatitis (or sometimes none at all), while in chronic hepatitis portal infiltrates are dense and prominent—the defining

feature of chronic hepatitis. Bridging necrosis and fibrosis are shown only for chronic hepatitis, but bridging necrosis

may also occur in more severe acute hepatitis.

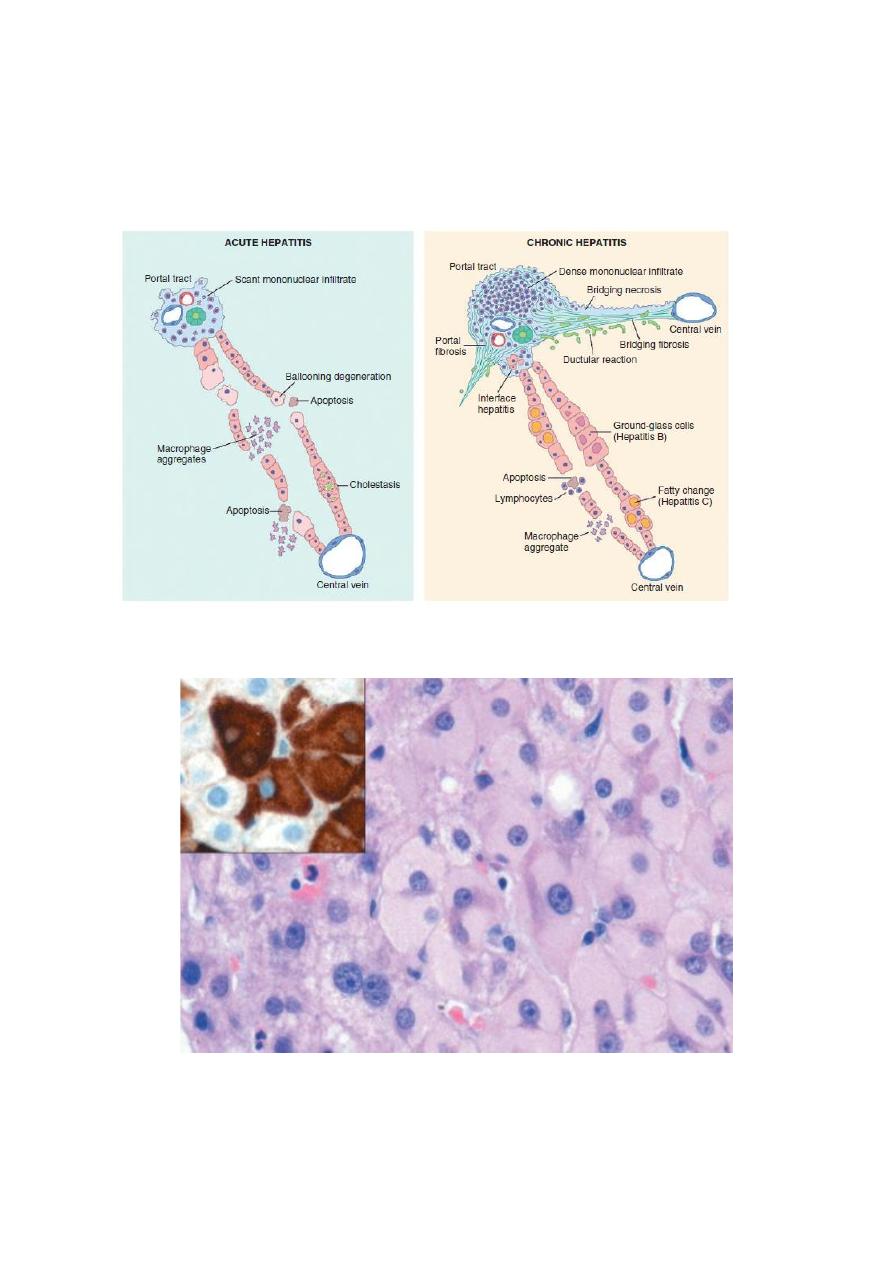

Fig. Ground-glass hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis B, caused by accumulation of hepatitis B surface antigen.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining shows the presence of abundant, finely granular pink cytoplasmic inclusions;

immunostaining (inset) with a specific antibody confirms the presence of surface antigen (brown).

Notes for VIRAL HEPATITIS

• (hepatitis A and E) never cause chronic hepatitis, only AcutE hepatitis.

4

Only the consonants (hepatitis B, C, D) have the potential to cause chronic disease .

• Hepatitis C is the single virus that is more often chronic than not (almost never

detected acutely; 85% or more of patients develop chronic hepatitis, 20% of whom

will develop cirrhosis).

• Hepatitis D, the delta agent, is a defective virus, requiring hepatitis B coinfection for

its own capacity to infect and replicate.

• The inflammatory cells in both acute and chronic viral hepatitis are mainly T cells.

• Patients with long-standing HBV or HCV infections are at increased risk for

development of HCC.

ALCOHOLIC AND NONALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER

DISEASE

Alcohol is a well-known cause of fatty liver disease in adults and can manifest

histologically as steatosis, steatohepatitis, and cirrhosis. In recent years, it has become

evident that another entity, so-called “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),” can

mimic the entire spectrum of hepatic changes associated with alcohol abuse. Since

the morphologic changes of alcoholic and NAFLD are indistinguishable, they are

discussed together

Three types of liver alterations are observed in fatty liver disease:

steatosis (fatty change), hepatitis (alcoholic or steatohepatitis), and fibrosis.

1. steatosis (fatty change):- accumulation of fat in hepatocytes (steatosis). The

pathogenesis of fatty liver is clearly depend on the intake of ethanol because it is

fully and rapidly reversible when the alcohol consumption is stopped.

Morphological Features:-

Grossly, fatty livers with widespread steatosis are large (weighing 4–6 kg or more),

soft, yellow, and greasy.

Microscopically: Hepatocellular fat accumulation typically begins in centrilobular

hepatocytes. The lipid droplets range from small (microvesicular) to large

(macrovesicular), the largest filling and expanding the cell and displacing the

nucleus.

As steatosis becomes more extensive, the lipid accumulation spreads outward from

the central vein to hepatocytes in the midlobule and then the periportal regions.

5

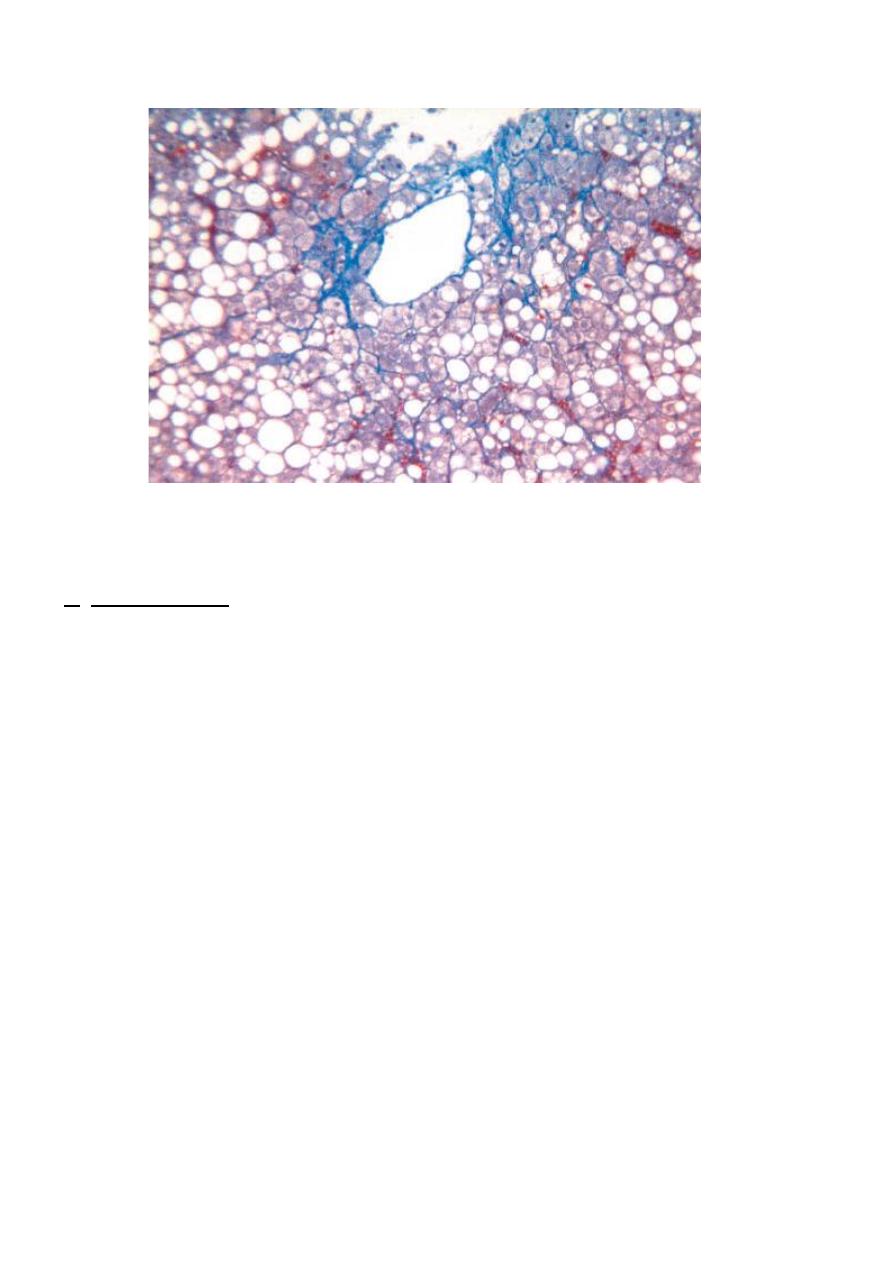

Fig. Fatty liver disease associated with chronic alcohol use. A mix of small and large fat droplets (seen as

clear vacuoles) is most prominent around the central vein and extends outward to the portal tracts. Some

fibrosis (stained blue) is present in a characteristic perisinusoidal

(Masson trichrome stain).

2. Steatohepatitis. These changes typically are more pronounced with alcohol use

than in NAFLD, but can be seen in either:

• Hepatocyte ballooning. Single or scattered foci of cells undergo swelling and

necrosis, these features are most prominent in the centrilobular regions

• Mallory-Denk bodies. These consist of tangled skeins of intermediate filaments

(including keratins 8 and 18) and are visible as eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions in

degenerating hepatocytes .

• Neutrophil infiltration. Predominantly neutrophilic infiltration may permeate the

lobule and accumulate around degenerating hepatocytes, particularly those containing

Mallory-Denk bodies. Lymphocytes and macrophages also may be seen in portal

tracts or parenchyma.

6

Fig. Hepatocyte injury in fatty liver disease associated with chronic alcohol use. (A) Clustered

inflammatory cells marking the site of a necrotic hepatocyte. A Mallory-Denk body is present in

another hepatocyte (arrow). (B) “Ballooned” hepatocytes (arrowheads) associated with clusters of

inflammatory cells. The inset stained for keratins 8 and 18 (brown) shows a ballooned cell (dotted

line) an immunoreactive Mallory-Denk body, leaving the cytoplasm “empty.”

7

3, Steatofibrosis. Fatty liver disease of all kinds has a distinctive pattern of scarring.

Like other changes, fibrosis appears first in the centrilobular region as central vein

sclerosis. fibrosis eventually link to portal tracts and then condense to create central

portal fibrous septa. As these become more prominent, the liver takes on a nodular,

cirrhotic appearance. Because in most cases the underlying cause persists, the

continual subdivision of established nodules by new, perisinusoidal scarring leads to

a classic micronodular cirrhosis . Early in the course, the liver is yellow-tan, fatty,

and enlarged, but with persistent damage over the course of years the liver is

transformed into a brown, shrunken, nonfatty organ composed of cirrhotic nodules

that are usually less than 0.3 cm in diameter—smaller than is typical for most chronic

viral

hepatitis.

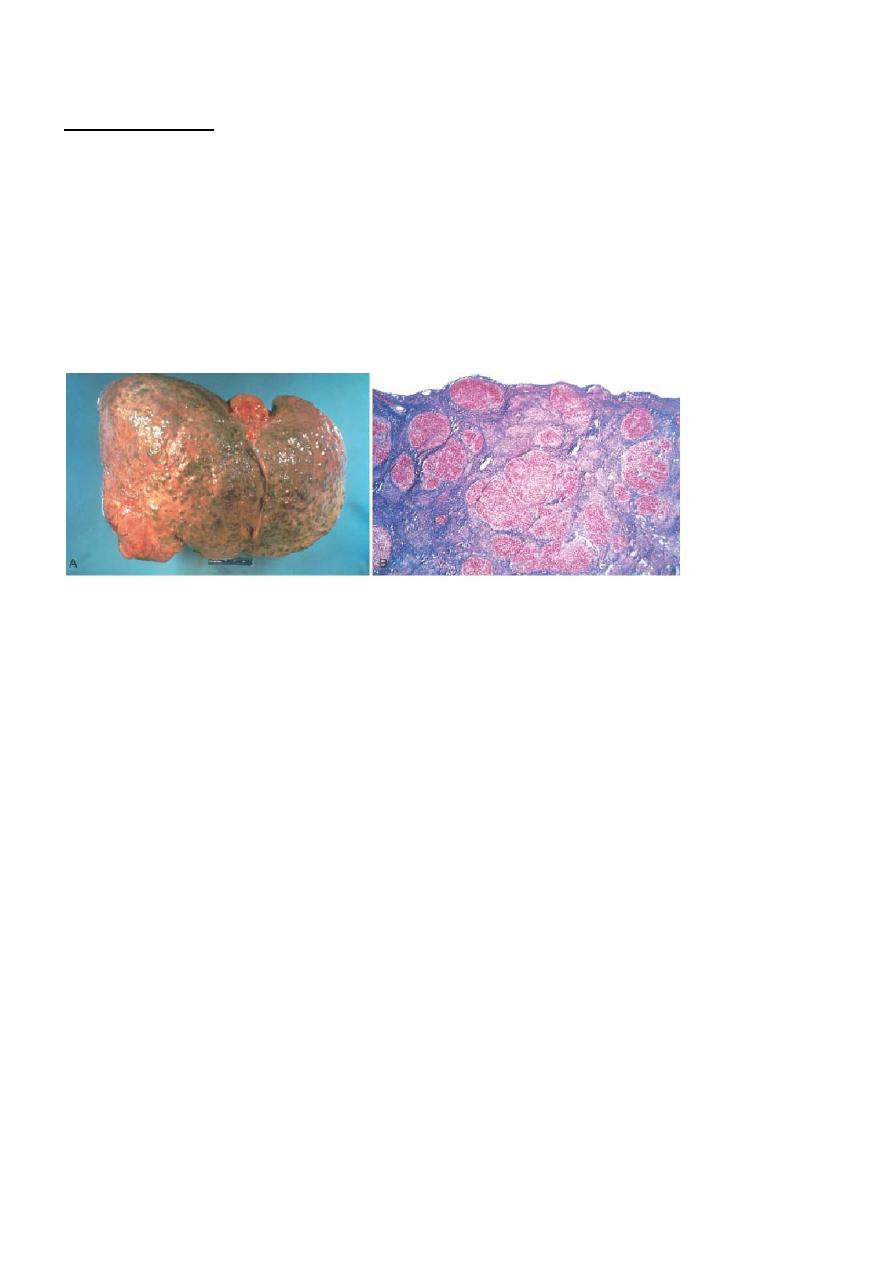

Alcoholic cirrhosis. A, The characteristic diffuse nodularity of the surface reflects the interplay between nodular

regeneration and scarring. The greenish tint of some nodules is due to bile stasis. A hepatocellular carcinoma is

present as a budding mass at the lower edge of the right lobe (lower left of figure). B, The microscopic view

shows nodules of varying sizes entrapped in blue-staining fibrous tissue. The liver capsule is at the top (Masson

trichrome).

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Between 90% and 100% of heavy drinkers develop fatty liver (i.e., hepatic steatosis),

and of those, 10% to 35% develop alcoholic hepatitis, whereas only 8% to 20% of

chronic alcoholics develop cirrhosis. Steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, and fibrosis may

develop sequentially or independently, so they do not necessarily represent a

sequential continuum of changes. Hepatocellular carcinoma arises in 10% to 20% of

patients with alcoholic cirrhosis.

Pathogenesis of fatty liver:

Within hepatocyte, ethanol

1. increases fatty acids synthesis

2. decreases mitochondrial oxidation of fatty acids

3. increases the production of the triglycerides

4. impairs the release of lipoproteins.

The cause of alcoholic hepatitis is uncertain, but it may stem from one or

more of the toxic byproducts of ethanol and its metabolites.

8

Inhirited Metabolic Liver Diseases

1-

HEMOCHROMATOSIS

Hemochromatosis is characterized by the excessive accumulation of body

iron, most of which is deposited in parenchymal organs such as the liver

and pancreas. Iron can also accumulate in the heart, joints, or endocrine

organs. Hemochromatosis (also known as primary or hereditary

hemochromatosis) is a homozygous-recessive inherited disorder that is

caused by excessive iron absorption.

Accumulation of iron in tissues, which may occur as a consequence of

parenteral administration of iron, usually in the form of transfusions, or

other causes is variably known as secondary hemochromatosis.

the total body iron pool ranges from 2 to 6 gm in normal adults; about 0.5

gm is stored in the liver, 98% of which is in hepatocytes. In

hemochromatosis, total iron accumulation may exceed 50 gm, over one

third of which accumulates in the liver.

Pathogenesis.

Whatever the underlying cause, the onset of disease typically occurs after

20 gm of stored iron have accumulated. Excessive iron appears to be

directly toxic to host tissues. Mechanisms of liver injury include the

following:

• Lipid peroxidation via iron-catalyzed free radical reactions

• Stimulation of collagen formation by activation of hepatic stellate cells

• DNA damage by reactive oxygen species, leading to lethal cell injury or

predisposition to HCC

The deleterious effects of iron on cells that are not fatally injured are

reversible, and removal of excess iron with therapy promotes recovery of

tissue function.

The

morphologic

changes

in

severe

hemochromatosis

are

characterized

9

(1) tissue deposition of hemosiderin in the following organs (in decreasing

order of severity): liver, pancreas, myocardium, pituitary gland, adrenal

gland, thyroid and parathyroid glands, joints, and skin;

(2) cirrhosis; and (3) pancreatic fibrosis. In the liver, iron becomes evident

first as golden-yellow hemosiderin granules in the cytoplasm of periportal

hepatocytes, which can be histochemically stained with Prussian blue .

With increasing iron load, there is progressive deposition in the rest of the

lobule, the bile duct epithelium, and Kupffer cells. At this stage, the liver

typically is slightly enlarged and chocolate brown. Fibrous septa develop

slowly, linking portal tracts to each other and leading ultimately to

cirrhosis in an intensely pigmented (very dark brown to black) liver.

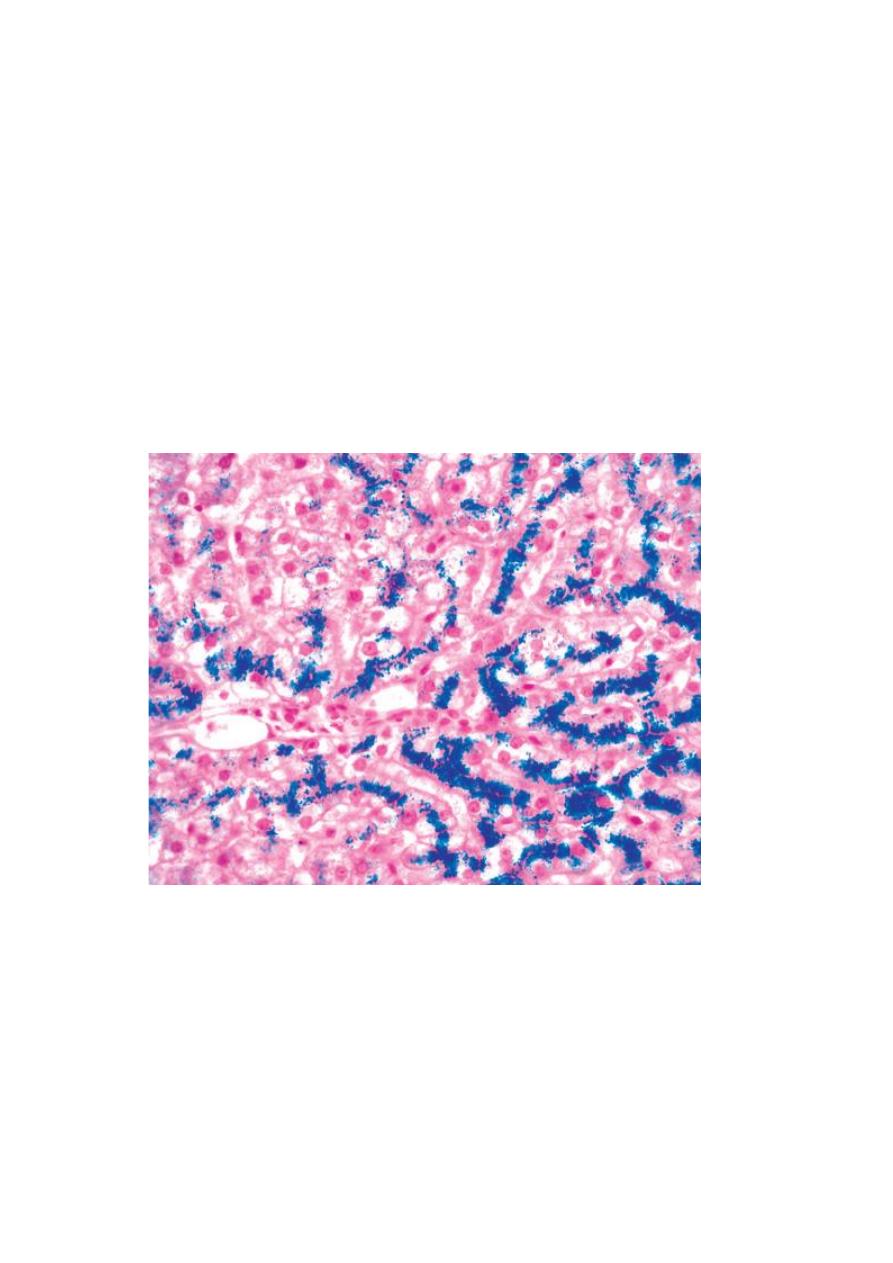

Fig. Hereditary hemochromatosis. In this Prussian blue–stained section, hepatocellular iron appears blue.

The parenchymal architecture is normal at this stage of disease, even with such abundant iron.

WILSON DISEASE

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutation of the ATP7B

gene (located on chromosome 13, encodes a transmembrane copper-transporting

ATPase, expressed on the hepatocyte canalicular membrane.), resulting in impaired

copper excretion into bile and a failure to incorporate copper into ceruloplasmin. This

disorder is marked by the accumulation of toxic levels of copper in many tissues and

10

organs, principally the liver, brain, and eye. Normally, 40% to 60% of ingested

copper is absorbed in the duodenum and proximal small intestine, and is transported

to the portal circulation complexed with albumin and histidine. Free copper

dissociates and is taken up by hepatocytes. Copper is incorporated into enzymes and

also binds to a α2-globulin (apoceruloplasmin) to form ceruloplasmin, which is

secreted into the blood. Excess copper is transported into the bile. Ceruloplasmin

accounts for 90% to 95% of plasma copper. Circulating ceruloplasmin is eventually

degraded within lysosomes, after which the released copper is excreted into bile. This

degradation/excretion pathway is the primary route for copper elimination.

Deficiency in the ATP7B protein causes a decrease in copper transport into bile,

impairs its incorporation into ceruloplasmin, and inhibits ceruloplasmin secretion into

the blood. These changes cause copper accumulation in the liver and a decrease in

circulating ceruloplasmin. The copper causes toxic liver injury.

Morphology. The liver often bears the brunt of injury, but the disease may also

present as a neurologic disorder. The hepatic changes are variable, ranging from

relatively minor to massive damage. Fatty change (steatosis) may be mild to

moderate. An acute hepatitis can show features mimicking acute viral hepatitis,

except possibly for the accompanying fatty change. The chronic hepatitis of Wilson

disease exhibits moderate to severe inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis, with the

particular features of macrovesicular steatosis and Mallory bodies. With progression

of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis will develop.

In the brain, toxic injury primarily affects the basal ganglia, particularly the putamen,

which shows atrophy and even cavitation. Nearly all patients with neurologic

involvement develop eye lesions called Kayser-Fleischer rings, green to brown

deposits of copper in Desçemet's membrane in the limbus of the cornea.