The pancreas

Dr. Ali Jaffer - Upper GI surgeon

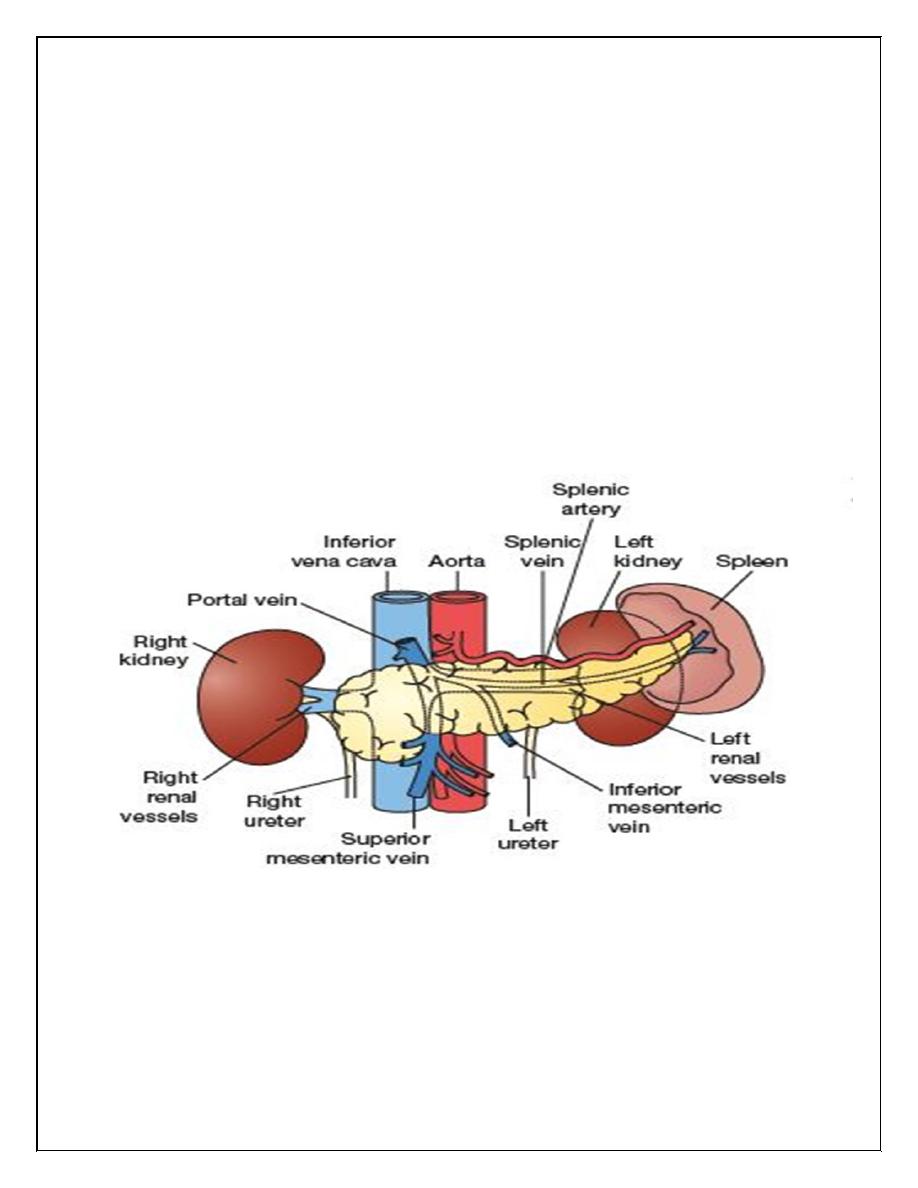

Anatomy

The pancreas is situated in the retroperitoneum. It is divided into a head, which occupies

30% of the gland by mass, and a body and tail, which together constitute 70%.

The head

lies within the curve of the duodenum, overlying the body of the second lumbar vertebra

and the vena cava.

The aorta and the superior mesenteric vessels lie behind the neck of the

gland.

Coming off the side of the pancreatic head and passing to the left and behind the

superior mesenteric vein is the uncinate process of the pancreas.

Behind the neck of the

pancreas, near its upper border, the superior mesenteric vein joins the splenic vein to form

the portal vein.

The tip of the pancreatic tail extends up to the splenic hilum.

Vasculature

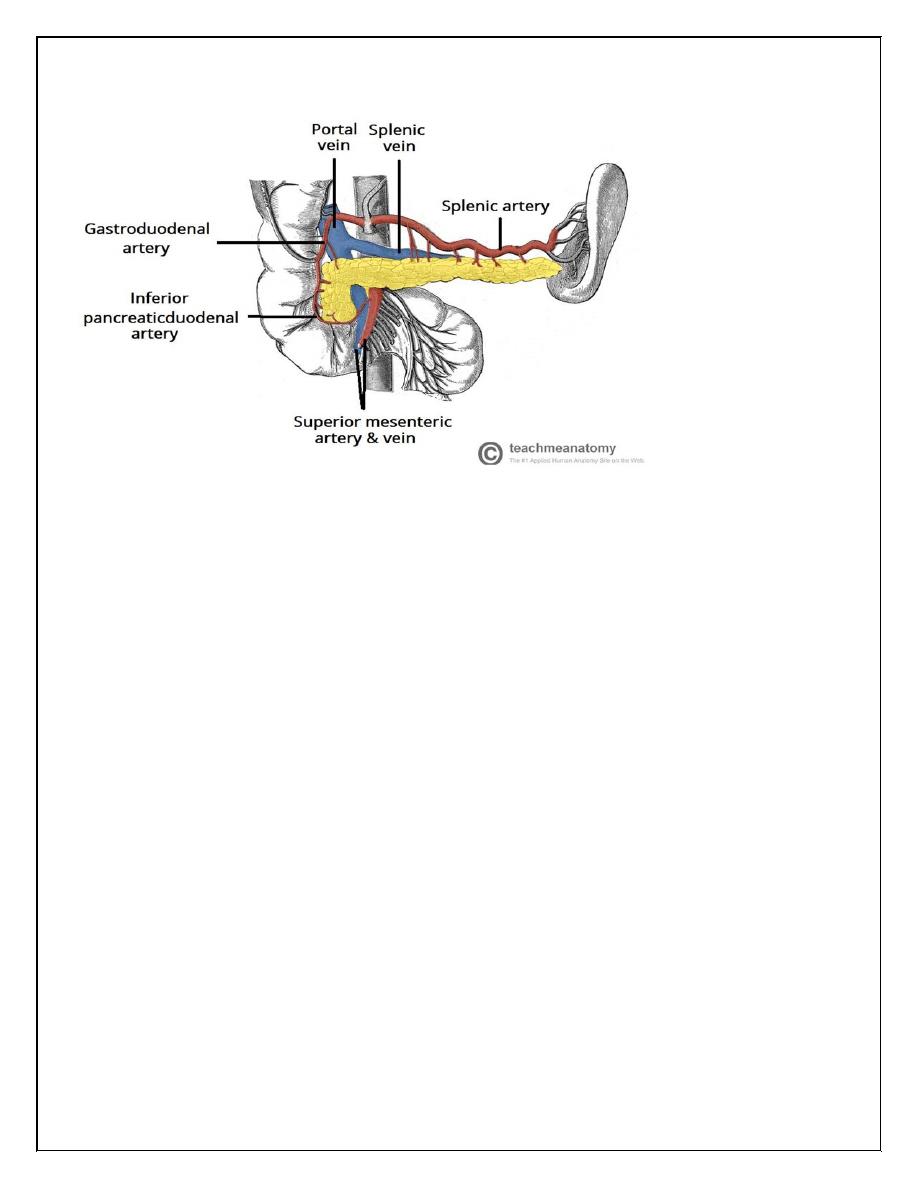

Arteries:

Splenic a., superior pancreaticoduodenal a

, inferior pancreaticoduodenal a.

Veins:

Splenic vein, superior mesenteric vein

Lympahatics:

The pancreas is drained by lymphatic

vessels that follow the arterial supply.

They empty into the pancreaticosplenal

nodes and the pyloric nodes, which in

turn drain

into the superior mesenteric and

coeliac lymph nodes.

INVESTIGATIONS

Estimation of pancreatic enzymes in body fluids

serum amylase, lipase

Pancreatic function tests

The nitroblue tetrazolium–para-aminobenzoic acid (NBT–PABA)

The pancreolauryl test

Faecal elastase

Imaging investigations

Ultrasonography: Ultrasonography is the initial investigation of choice in patients with

jaundice to determine whether or not the bile duct is dilated, the coexistence of gallstones or

gross disease within the liver such as metastases. It may also define the presence or absence of

a mass in the pancreas . However, obesity and overlying bowel gas often make interpretation

of the pancreas itself unsatisfactory.

b. Computed tomography: Most significant pathologies within the pancreas can be diagnosed

on high-quality CT scans.

c. Magnetic resonance imaging: Magnetic resonance cholangiography and pancreatography

(MRCP) may well replace diagnostic endoscopic cholangiography and pancreatography

(ERCP) as it is non-invasive and less expensive

d. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: ERCP is performed using a

side-viewing fibreoptic duodenoscope. The ampulla of Vater is intubated, and contrast is

injected into the biliary and pancreatic ducts to display the anatomy radiologically.

Diagnostic

and therapeutic

e. Endoscopic ultrasound: This is particularly useful in identifying small tumours that may

not show up well on CT or MRI, and in demonstrating the relationship of a pancreatic tumour

to major vessels nearby.

Transduodenal or transgastric fine needle aspiration (FNA) or Trucut

biopsy performed under EUS guidance avoids spillage of tumour cells into the peritoneal

cavity.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

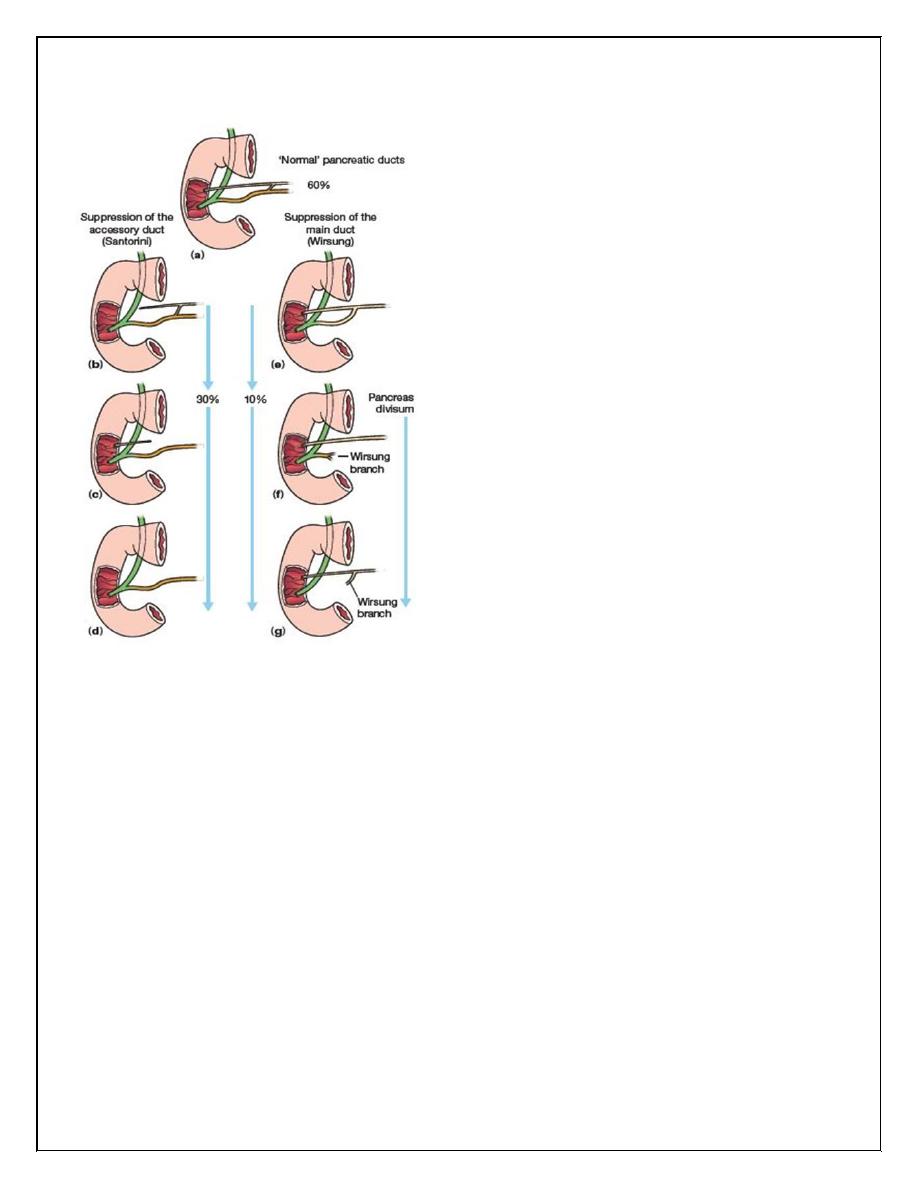

Pancreas divisum

occurs when the embryological ventral and dorsal parts of the pancreas fail to fuse. The dorsal

pancreatic duct becomes the main pancreatic duct and drains most of the pancreas through the

minor or accessory papilla. The incidence of pancreas divisum ranges from 5% to10%

.Pancreas divisum found incidentally in an asymptomatic person does not warrant any

intervention. The incidence of pancreas divisum ranges from 25–50% in patients with

recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic pain. The minor papilla is

substantially smaller than the major papilla (and many of these patients probably have

papillary stenosis). A large volume of secretions flowing through a narrow papilla probably

leads to incomplete drainage, which may then cause obstructive pain or pancreatitis.

Idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis, pancreas divisum should be excluded. The diagnosis can be

arrived at by MRCP, EUS or ERCP, augmented by injection of secretin if necessary.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy and stenting of the minor papilla may relieve the symptoms.

Surgical intervention can take the form of sphincteroplasty, pancreatojejunostomy or even

resection of the pancreatic head.

Annular pancreas

This is the result of failure of complete rotation of the ventral pancreatic bud during

development, so that a ring of pancreatic tissue surrounds the second or third part of the

duodenum.

It is most often seen in association with congenital duodenal stenosis or atresia

and is therefore more prevalent in children with Down syndrome. The usual treatment is

bypass (duodenoduodenostomy). The disease may occur in later life as one of the causes of

pancreatitis.

Ectopic pancreas

Islands of ectopic pancreatic tissue can be found in the submucosa in parts of the stomach,

duodenum or small intestine (including Meckel’s diverticulum), the gall bladder, adjoining the

pancreas, in the hilum of the spleen and within the liver.

Ectopic pancreas may also be found

in the wall of an alimentary tract duplication cyst.

INJURIES TO THE PANCREAS

External injury

Presentation and management

The pancreas, its somewhat protected location in the retroperitoneum, is not frequently

damaged in blunt abdominal trauma. If there is damage to the pancreas, it is often concomitant

with injuries to other viscera, especially the liver, the spleen and the duodenum. Pancreatic

injuries may range from a contusion or laceration of the parenchyma without duct disruption

to major parenchymal destruction with duct disruption (sometimes complete transection) and,

rarely, massive destruction of the pancreatic head.

Blunt pancreatic trauma usually presents with epigastric Pain with the progressive

development of more severe pain due to the sequelae of leakage of pancreatic fluid into the

surrounding tissues. A rise in serum amylase occurs in most cases.

A CT scan of the pancreas

will delineate the damage that has occurred to the pancreas.

If there is doubt about duct

disruption, an urgent ERCP should be sought. MRCP may also provide the answer.

Support with intravenous fluids and a ‘nil by mouth’ regimen should be instituted while these

investigations are performed.

It is preferable to manage conservatively at first, investigate

and, once the extent of the damage has been ascertained, undertake appropriate action.

Operation is indicated if there is disruption of the main pancreatic duct; in almost all other

cases, the patient will recover with conservative management.

Penetrating trauma to the upper abdomen or the back carries a higher chance of pancreatic

injury.

In penetrating injuries, especially if other organs are injured and the patient’s condition

is unstable, there is a greater need to perform an urgent surgical exploration.

Sequlae

Death, in acute phase as a result of bleeding from associated injuries.

Persistent drain output in 1/3 of patients

Duct stricture resulting in recurrent episodes of pancreatitis.

Pancreatic pseudocyst.

Iatrogenic injury

This can occur in several ways:

● Injury to the tail of the pancreas during splenectomy, resulting in a pancreatic fistula.

● Injury to the pancreatic head and the accessory pancreatic duct (Santorini), which is the

main duct in 7% of patients, during Billroth II gastrectomy

● Enucleation of islet cell tumours of the pancreas can result in fistulae.

● Duodenal or ampullary bleeding following sphincterotomy.

Pancreatic fistula

Management of pancreatic fistulae

Tests

● Measure amylase level in fluid

● Determine the anatomy of the fistula

● Check if the main pancreatic duct is blocked or disrupted

Measures

● Correct fluid and electrolyte imbalances

● Protect the skin

● Drain adequately

● Parenteral or nasojejunal feeding

● Octreotide to suppress secretion

● Relieve pancreatic duct obstruction if possible (ERCP andstent)

● Treat underlying cause

Acute pancreatitis

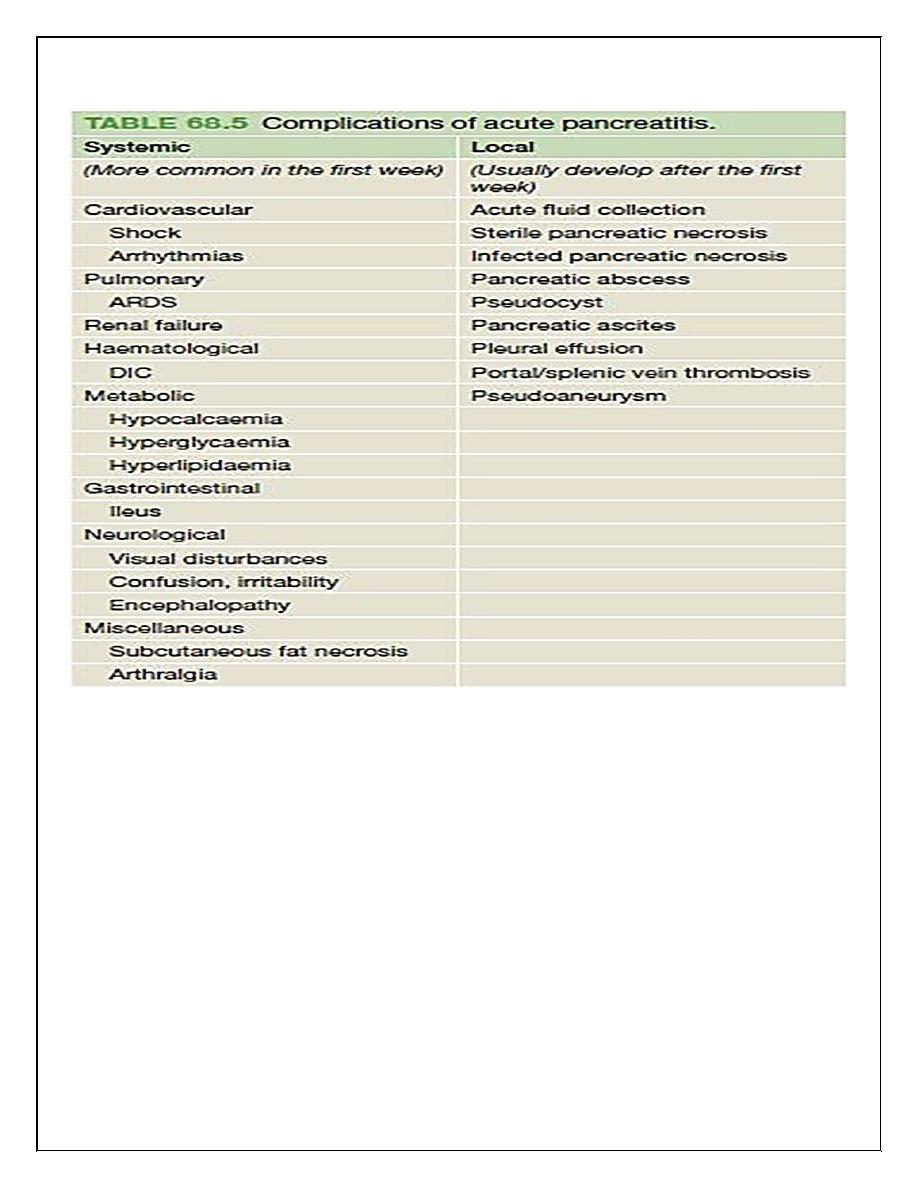

The underlying mechanism of injury in pancreatitis is thought to be premature activation of

pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas, leading to a process of autodigestion.

Once cellular

injury has been initiated, the inflammatory process can lead to pancreatic oedema,

haemorrhage and, eventually, necrosis.

As inflammatory mediators are released into the

circulation, systemic complications can arise, such as haemodynamic instability, bacteraemia

(due to translocation of gut flora), acute respiratory distress syndrome and pleural effusions,

gastrointestinal haemorrhage, renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation

(DIC).

The majority of patients will have a mild attack of pancreatitis, the mortality from

which is around 1%. Severe acute pancreatitis is seen in 5–10% of patients, and is

characterised by pancreatic necrosis, a severe systemic inflammatory response and often

multi-organ failure.

In those who have a severe attack of pancreatitis, the mortality varies

from 20 to 50%.

Acute pancreatitis has an early phase that usually lasts a week. It is characterised by a

systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) which – if severe – can lead to transient

or persistent organ failure (deemed persistent if it lasts for over 48 hours). About one-third of

deaths occur in the early phase of the attack, from multiple organ failure. The late phase is

seen typically in those who suffer a severe attack, and can run from weeks to months. It is

characterised by persistent systemic signs of inflammation, and/or local complications,

particularly fluid collections and peripancreatic sepsis. Deaths occurring after the first week

of onset are often due to septic complications.

Possible causes of acute pancreatitis

● Gallstones

● Alcoholism ( Gallstones and Alcoholism contribute to 50-70% of cases)

● Post ERCP 1-3 %

● Abdominal trauma

● Following biliary, upper gastrointestinal or cardiothoracic surgery

● Ampullary tumour

● Drugs (corticosteroids, azathioprine, asparaginase, valproic acid, thiazides, oestrogens)

● Hyperparathyroidism

● Hypercalcaemia

● Pancreas divisum

● Autoimmune pancreatitis

● Hereditary pancreatitis

● Viral infections (mumps, coxsackie B)

● Malnutrition

● Scorpion bite

● Idiopathic

Clinical presentation

Pain characteristically develops quickly, reaching maximum intensity within minutes and

persists for hours or even days. The pain is frequently severe, constant and refractory to the

usual doses of analgesics. epigastrium but may be localised to either upper quadrant or felt

diffusely throughout the abdomen. There is radiation to the back in about 50% of patients,

and some patients may gain relief by sitting or leaning forwards.

Nausea, repeated vomiting

and retching. The retching may persist despite the stomach being kept empty by nasogastric

aspiration. Hiccoughs may be due to gastric distension or irritation of the diaphragm.

On examination, the patient may be well or gravely ill.

Tachypnoea , tachycardia is usual,

and hypotension .

The body temperature is often normal or even subnormal. Mild icterus can

be caused by biliary obstruction in gallstone pancreatitis.

Bleeding into the fascial planes can

produce bluish discolouration of the flanks (Grey Turner’s sign) or umbilicus (Cullen’s sign).

Neither sign is pathognomonic of acute pancreatitis; Cullen’s sign was first described in

association with rupture of an ectopic pregnancy. Subcutaneous fat necrosis may produce

small, red, tender nodules on the skin of the legs.

Abdominal examination may reveal

distension due to ileus. There is usually muscle guarding in the upper abdomen.

A pleural

effusion is present in 10–20% of patients. Pulmonary oedema and pneumonitis

Investigations

A serum amylase level three times above normal

serum levels lipase

contrast- enhanced CT.

ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY

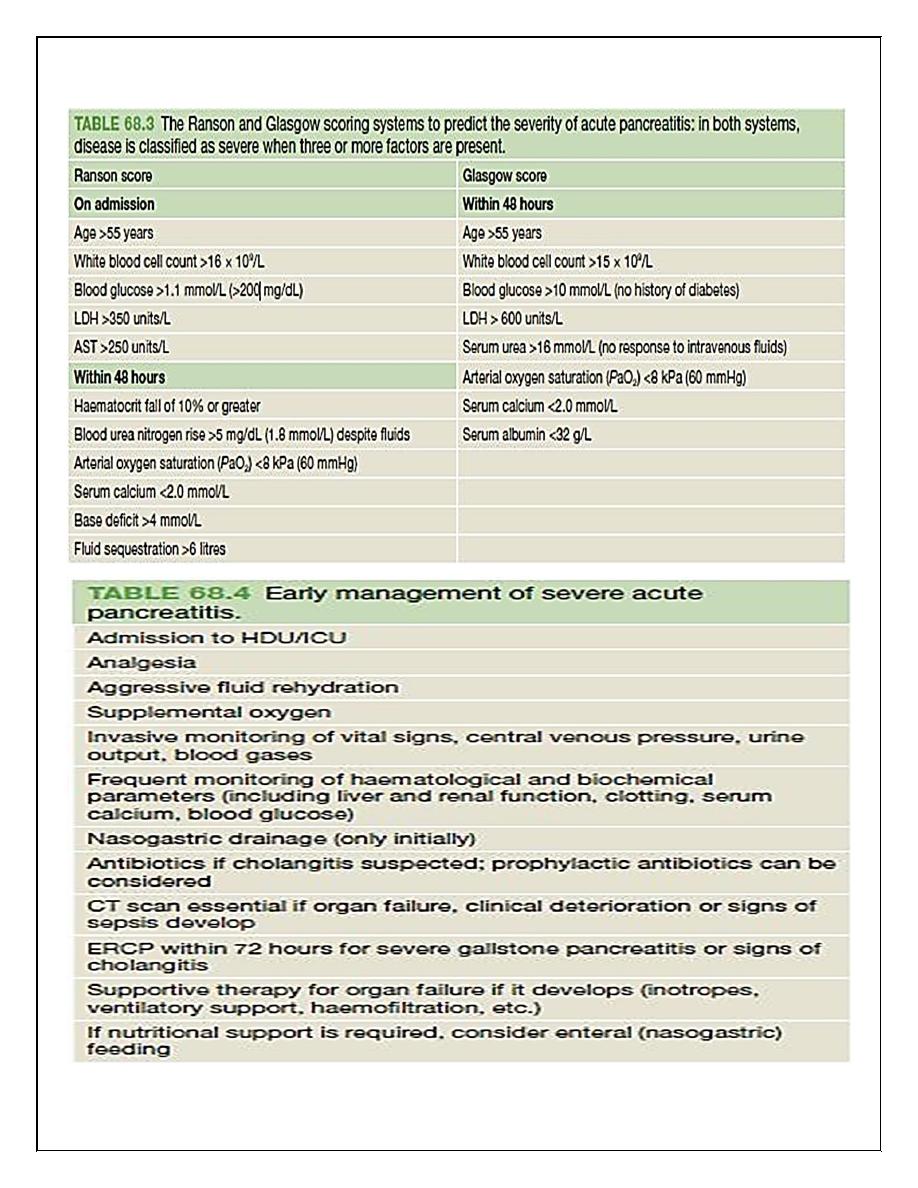

Severity stratification assessments should be performed in patients at 24 hours, 48 hours and

7 days after admission.

The Ranson and Glasgow scoring systems are specific for acute

pancreatitis, and a score of 3 or more at 48 hours indicates a severe attack

Regardless of the system used, persisting organ failure indicates a severe attack. A serum

C-reactive protein level >150 mg/L at 48 hours after the onset of symptoms is also an

indicator of severity.

Mild acute pancreatitis:

no organ failure;

no local or systemic complications.

Moderately severe acute pancreatitis:

organ failure that resolves within 48 hours (transient

organ failure); and/or

local or systemic complications without persistent organ failure.

Severe acute pancreatitis:

persistent organ failure (>48 hours);

single organ failure;

multiple organ failure.

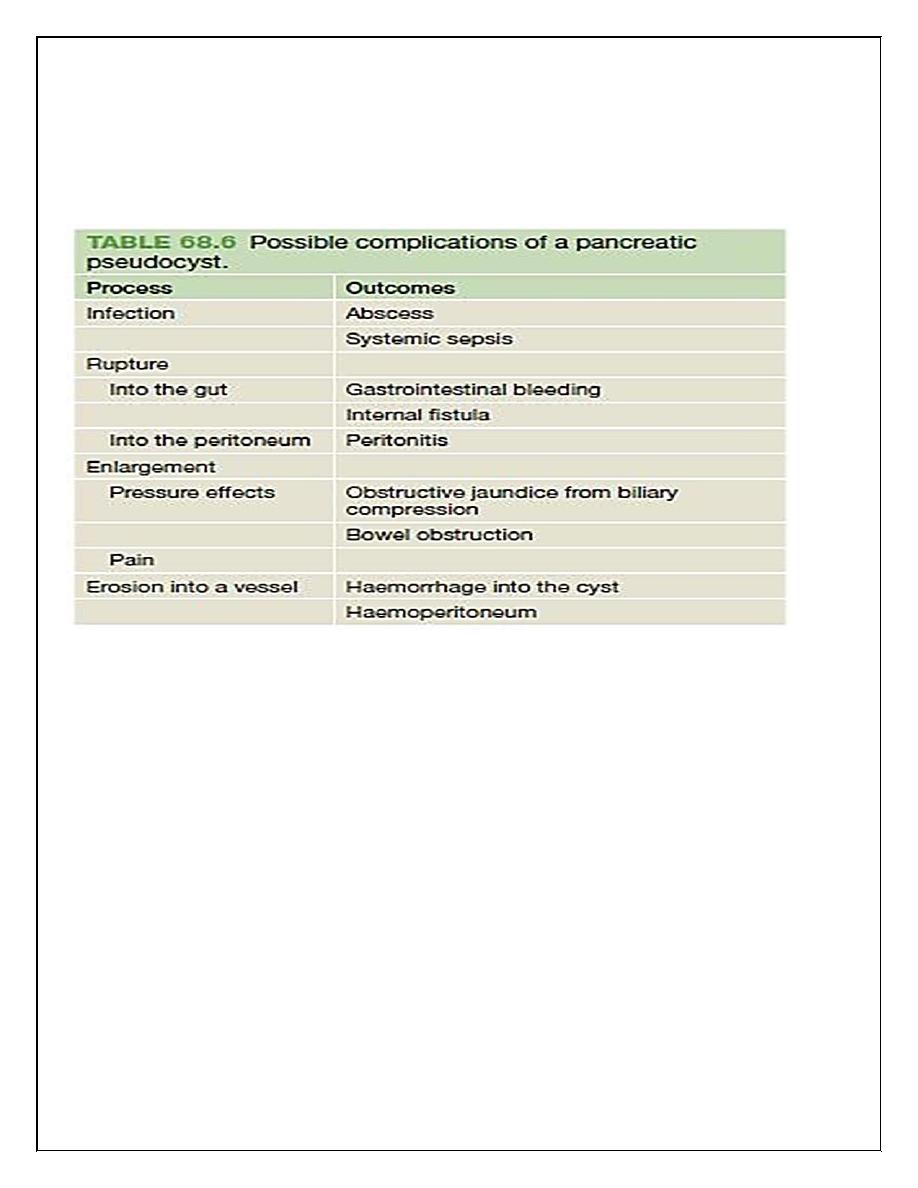

PSEUDOCYST

A pseudocyst is a collection of amylase-rich fluid enclosed in a well-defined wall of fibrous

or granulation tissue. Formation of a pseudocyst requires 4 weeks or more from the onset of

acute pancreatitis.

A pseudocyst is usually identified on ultrasound or a CT scan.

EUS and aspiration of the cyst

fluid. The fluid should be sent for measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels,

amylase levels and cytology.

Fluid from a pseudocyst typically has a low CEA level, and

levels above 400 ng/mL are suggestive of a mucinous neoplasm.

Pseudocyst fluid usually

has a high amylase level, but that is not diagnostic, as a tumour that communicates with the

duct system may yield similar findings. Cytology typically reveals inflammatory cells in

pseudocyst fluid.

Pseudocysts will resolve spontaneously in most instances,

but complications can develop .

Pseudocysts that are thick-walled or large (over 6 cm in diameter), have lasted for a long

time (over 12 weeks), or have arisen in the context of chronic pancreatitis are less likely to

resolve spontaneously.

Therapeutic interventions are advised only if the pseudocyst causes

symptoms, if complications develop, or if a distinction has to be made between a pseudocyst

and a tumour.

Percutaneous drainage to the exterior under radiological guidance should be avoided. It

carries a very high likelihood of recurrence. Moreover, it is not advisable unless one is

absolutely certain that the cyst is not neoplastic and that it has no communication with the

pancreatic duct (or else a pancreaticocutaneous fistula will develop).

Endoscopic drainage

usually involves puncture of the cyst through the stomach or duodenal wall under EUS

guidance, and placement of a tube drain with one end in the cyst cavity and the other end in

the gastric lumen.

Surgical drainage involves internally draining the cyst into the gastric or

jejunal lumen

STERILE AND INFECTED PANCREATIC NECROSIS

Refers to a diffuse or focal area of non-viable parenchyma.

Acute necrotic collection (ANC). This is typically an intra or extrapancreatic collection

containing fluid and necrotic material, with no definable wall.

Gradually, over a period of

over 4 weeks, this may develop a well-defined inflammatory capsule, and evolve into what

is termed walled-off necrosis (WON).

Collections associated with necrotising pancreatitis are sterile to begin with but often

become subsequently infected, probably due to translocation of gut bacteria.

Infected

necrosis is associated with a mortality rate of up to 50%.

Sterile necrotic material should not

be drained or interfered with. But if the patient shows signs of sepsis, then one should

determine whether the collection is infected

Dx: aspiration under Ct scan guidance. (the needle should never pass through hollow

viscera). Rx: if the aspirated is purulent, the patient should be kept on antibiotics according

to sensitivity and drain inserted for drainage. The drain should be with larger size when the

aspirate is thick content. if sepsis persist this need pancreatic necrosectomy. Patients with

peripancreatic sepsis are ill for long periods of time, and may require management in an

intensive care unit. Nutritional support is essential. The parenteral and nasojejunal

approaches are more popular (on the assumption that they rest the pancreas).

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive inflammatory disease in which there is irreversible

destruction of pancreatic tissue. Its clinical course is characterised by severe pain and, in the

later stages, exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Aetiology and pathology

Alcoholism 60-70%

Duct obstruction due to trauma, acute pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer

Congenital anomalies Hereditary pancreatitis

Cystic fibrosis

Hyperlipidemia

Hypercalcemia

Autoimmune pancreatistis (IgG4 phenomena)

Idioathic

*** At the onset of the disease, the pancreas may appear normal. Later, the pancreas enlarges

and becomes hard as a result of fibrosis. The ducts become distorted and dilated with areas

of both stricture formation and ectasia. Calcified stones form within the ducts. The ducts

may become occluded with a gelatinous proteinaceous fluid and debris, and inflammatory

cysts may form. Histologically, the lesions affect the lobules, producing ductular metaplasia

and atrophy of acini, hyperplasia of duct epithelium and interlobular fibrosis.

Clinical features

Pain; the site of the pain is depend on the site of the disease. Head of pancreas; the pain felt

in the epigastric and right subcostal region, whereas if the disease is limited to the body and

tail, the pain felt in the left subcostal region and back.

Nausea is common, vomiting may develop.

Weight loss

The patient’s lifestyle is gradually destroyed by pain, analgesic dependence, weight loss and

inability to work.

Loss of exocrine function leads to steatorrhoea in more than 30% of patients with chronic

pancreatitis.

Loss of endocrine function and the development of diabetes

Infection

Investigations

Only in the early stages of the disease will there be a rise in serum amylase.

Tests of pancreatic function merely confirm the presence of pancreatic insufficiency or that

more than 70% of the gland has been destroyed.

Pancreatic calcifications may be seen on abdominal X-ray. CT or MRI scan will show the

outline of the gland, the main area of damage and the possibilities for surgical correction, An

MRCP will identify the presence of biliary obstruction and the state of the pancreatic duct.

ERCP is the most accurate way of elucidating the anatomy of the duct.

EUS

Medical treatment of chronic pancreatitis

Treat the addiction, Help the patient to stop alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking,

Involve a dependency counsellor or a psychologis, Alleviate abdominal pain

Eliminate obstructive factors (duodenum, bile duct, pancreatic duct)

Escalate analgesia in a stepwise fashion, Refer to a pain management specialist, For

intractable pain, consider CT/EUS-guided coeliac axis block

Nutritional and pharmacological measures, Diet: low in fat and high in protein and

carbohydrates, Pancreatic enzyme supplementation with meals

Correct malabsorption of the fat-soluble vitamins and vitaminB12, Micronutrient therapy

with methionine, vitamins C & E, selenium (may reduce pain and slow disease progression)

Steroids (only in autoimmune pancreatitis, for relief of symptoms)

Medium-chain triglycerides in patients with severe fat malabsorption (they are directly

absorbed by the small intestine without the need for digestion)

Reducing gastric secretions may help

Treat diabetes mellitus

Endoscopic, radiological or surgical interventions are indicated mainly to relieve obstruction

of the pancreatic duct, bile duct or the duodenum, or in dealing with complications (e.g.

pseudocyst, abscess, fistula, ascites or variceal haemorrhage).

Prognosis

Chronic pancreatitis is a difficult condition to manage. Patients often suffer a gradual decline

in their professional, social and personal lives.

The pain may abate after a surgical or percutaneous intervention, but tends to return over a

period of time.

In a proportion of patients, the inflammation may gradually burn out over a

period of years, with disappearance of the pain, leaving only the exocrine and endocrine

insufficiencies.

Development of pancreatic cancer is a risk in those who have had the disease for more than

20 years.

New symptoms or a change in the pattern of symptoms should be investigated and

malignancy excluded.