1

Clostridium Species

The clostridia are large anaerobic, gram-positive, motile rods. Many species

decompose proteins or form toxins, and some do both. Their natural habitat is the soil

or the intestinal tract of animals and humans, where they live as saprophytes. Among

the pathogens are the organisms causing botulism, tetanus, gas gangrene, and

pseudomembranous colitis.

Morphology & Identification

Typical Organisms

Spores of clostridia are usually wider than the diameter of the rods in which they

are formed. In the various species, the spore is placed centrally, subterminally, or

terminally. Most species of clostridia are motile and possess peritrichous flagella.

Culture

Clostridia are anaerobes and grow under anaerobic conditions; a few species are

aero-tolerant and will also grow in ambient air.in general, the clostridia grow well on

the blood-enriched media used to grow anaerobes and on other media used to culture

anaerobes .

Colony Forms

Some clostridia produce large raised colonies (eg, C perfringens); others produce

smaller colonies (eg, C tetani). Some clostridia form colonies that spread on the agar

surface. Many clostridia produce a zone of hemolysis on blood agar. C perfringens

typically produces multiple zones of hemolysis around colonies.

Growth Characteristics

Clostridia can ferment a variety of sugars; many can digest proteins. Milk is turned

acid by some and digested by others and undergoes "stormy fermentation" (ie, clot

torn by gas) with a third group (eg, C perfringens). Various enzymes are produced by

different species .

Antigenic Characteristics

Clostridia share some antigens but also possess specific soluble antigens that permit

grouping by precipitin tests.

Clostridium Botulinum

Clostridium botulinum causes botulism is worldwide in distribution; it is found in

soil and occasionally in animal feces.

2

Types of C botulinum are distinguished by the antigenic type of toxin they produce.

Spores of the organism are highly resistant to heat, withstanding 100 °C for several

hours. Heat resistance is diminished at acid pH or high salt concentration.

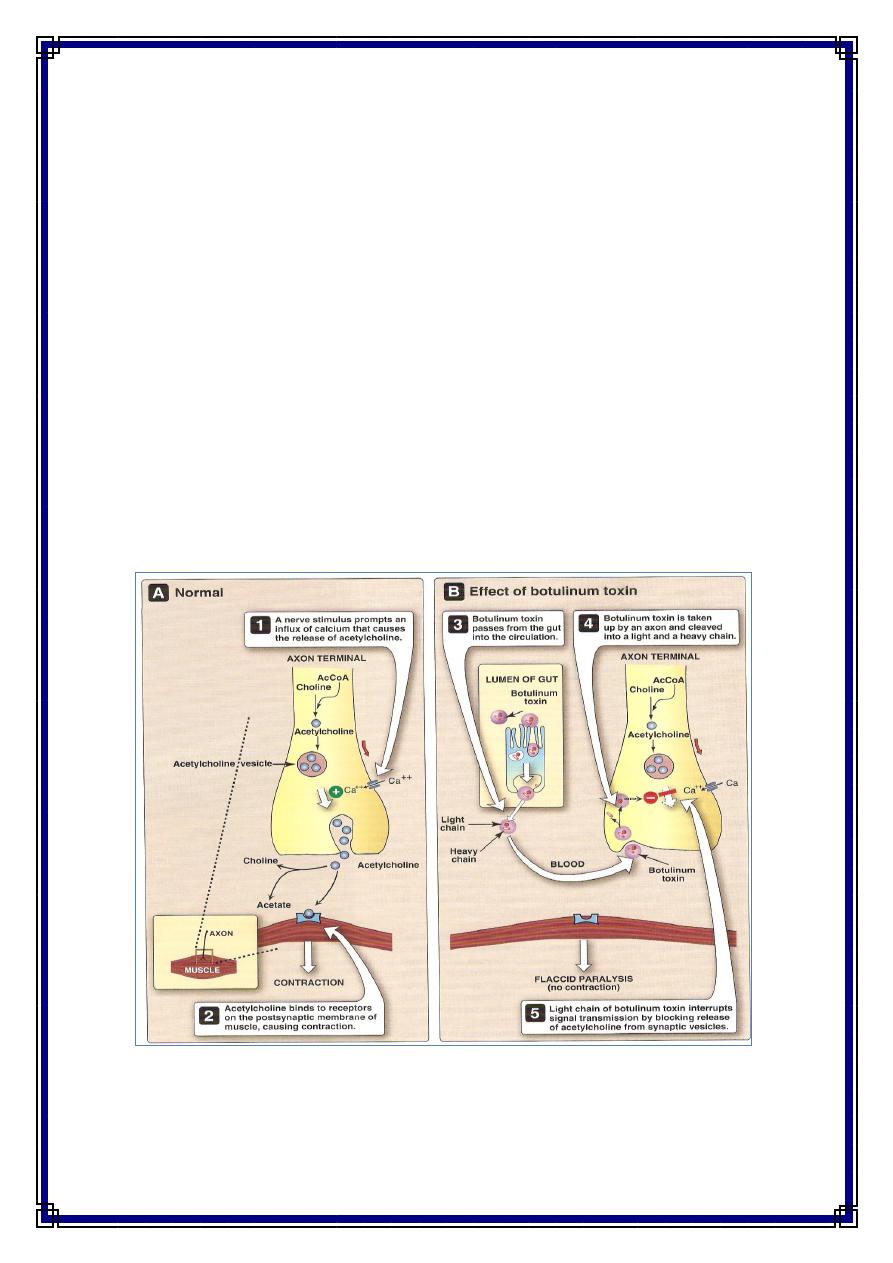

Toxin

During the growth of C botulinum and during autolysis of the bacteria, toxin is

liberated into the environment. . Types A and B have been associated with a variety of

foods and type E predominantly with fish products. toxin is a 150,000-MW protein

that is cleaved into 100,000-MW and 50,000-MW protein subunits linked by a

disulfide bond. Botulinum toxin is absorbed from the gut and binds to receptors of

presynaptic membranes of motor neurons of the peripheral nervous system and cranial

nerves. Proteolysis—by the light chain of botulinum toxin of the target SNARE

proteins in the neurons inhibits the release of acetylcholine at the synapse, resulting in

lack of muscle contraction and paralysis which called Flaccid paralysis . The SNARE

proteins are synaptobrevin, SNAP 25, and syntaxin. The toxins of C botulinum types

A and E cleave the 25,000-MW SNAP-25. Type B toxin cleaves synaptobrevin. C

botulinum toxins are among the most toxic substances known . The lethal dose for a

human is probably about 1–2 µg. The toxins are destroyed by heating for 20 minutes

at 100 °C.

3

Pathogenesis

Although C botulinum types A and B have been implicated in cases of wound

infection and botulism, most often the illness is not an infection. Rather, it is an

intoxication resulting from the ingestion of food in which C botulinum has grown and

produced toxin. The most common offenders are spiced, smoked, vacuum-packed, or

canned alkaline foods that are eaten without cooking. In such foods, spores of C

botulinum germinate; under anaerobic conditions, vegetative forms grow and produce

toxin.

Clinical Findings

Symptoms begin 18–24 hours after ingestion of the toxic food, with visual

disturbances (incoordination of eye muscles, double vision), inability to swallow, and

speech difficulty; signs of bulbar paralysis are progressive, and death occurs from

respiratory paralysis or cardiac arrest. Gastrointestinal symptoms are not regularly

prominent. There is no fever. The patient remains fully conscious until shortly before

death. The mortality rate is high. Patients who recover do not develop antitoxin in the

blood.

In the United States, infant botulism is as common as or more common than the

classic form of paralytic botulism associated with the ingestion of toxin-contaminated

food. The infants in the first months of life develop poor feeding, weakness, and signs

of paralysis ("floppy baby"). Infant botulism may be one of the causes of sudden

infant death syndrome. C botulinum and botulinum toxin are found in feces but not in

serum. It is assumed that C botulinum spores are in the babies' food, yielding toxin

production in the gut.

Diagnostic Laboratory Tests

Toxin can often be demonstrated in serum from the patient, and toxin may be found

in leftover food. Mice injected intraperitoneally die rapidly. The antigenic type of

toxin is identified by neutralization with specific antitoxin in mice. C botulinum may

be grown from food remains and tested for toxin production, but this is rarely done

and is of questionable significance. In infant botulism, C botulinum and toxin can be

demonstrated in bowel contents but not in serum. Toxin may be demonstrated by

passive hemagglutination or radioimmunoassay.

Treatment

Potent antitoxins to three types of botulinum toxins have been prepared in horses.

Since the type responsible for an individual case is usually not known, trivalent (A, B,

E) antitoxin must be promptly administered intravenously with customary

precautions. Adequate ventilation must be maintained by mechanical respirator, if

necessary. These measures have reduced the mortality rate from 65% to below 25%.

4

Epidemiology, Prevention, & Control

Since spores of C botulinum are widely distributed in soil, they often contaminate

vegetables, fruits, and other materials. A large restaurant-based outbreak was

associated with sautéed onions. When such foods are canned or otherwise preserved,

they either must be sufficiently heated to ensure destruction of spores or must be

boiled for 20 minutes before consumption. Strict regulation of commercial canning

has largely overcome the danger of widespread outbreaks, but commercially prepared

foods have caused deaths. A chief risk factor for botulism lies in home-canned foods,

particularly string beans, corn, peppers, olives, peas, and smoked fish or vacuum-

packed fresh fish in plastic bags. Toxic foods may be spoiled and rancid, and cans

may "swell," or the appearance may be innocuous. The risk from home-canned foods

can be reduced if the food is boiled for more than 20 minutes before consumption.

Toxoids are used for active immunization of cattle in South Africa.

Clostridium Tetani

Clostridium tetani, which causes tetanus, is worldwide in distribution in the soil

and in the feces of horses and other animals. Several types of C tetani can be

distinguished by specific flagellar antigens. All share a common O (somatic) antigen,

which may be masked, and all produce the same antigenic type of neurotoxin,

tetanospasmin.

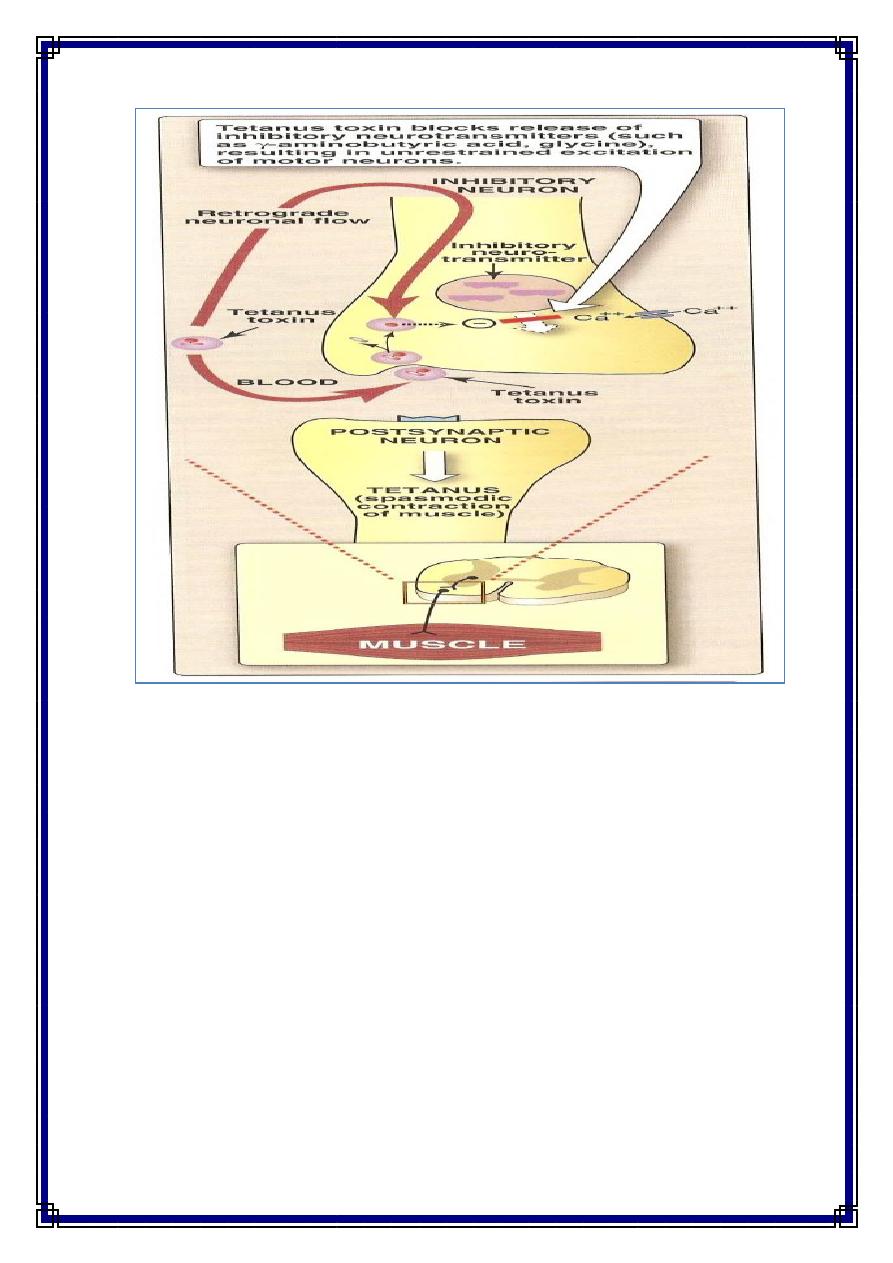

Toxin

The vegetative cells of C tetani produce the toxin tetanospasmin , the toxin initially

binds to receptors on the presynaptic membranes of motor neurons. It then migrates

by the retrograde axonal transport system to the cell bodies of these neurons to the

spinal cord and brain stem. The toxin diffuses to terminals of inhibitory cells,

including both glycinergic interneurons and aminobutyric acid-secreting neurons from

the brain stem. The toxin degrades synaptobrevin, a protein required for docking of

neurotransmitter vesicles on the presynaptic membrane. Release of the inhibitory

glycine and γ-aminobutyric acid is blocked, and the motor neurons are not inhibited.

Hyperreflexia, muscle spasms, and spastic paralysis result. Extremely small amounts

of toxin can be lethal for humans.

5

Pathogenesis

C tetani is not an invasive organism. The infection remains strictly localized in the

area of devitalized tissue (wound, burn, injury, umbilical stump, surgical suture) into

which the spores have been introduced. The volume of infected tissue is small, and

the disease is almost entirely a toxemia. Germination of the spore and development of

vegetative organisms that produce toxin are aided by (1) necrotic tissue, (2) calcium

salts, and (3) associated pyogenic infections, all of which aid establishment of low

oxidation-reduction potential.

The toxin released from vegetative cells reaches the central nervous system and

rapidly becomes fixed to receptors in the spinal cord and brain stem and exerts the

actions described above.

Clinical Findings

The incubation period may range from 4–5 days to as many weeks. The disease is

characterized by tonic contraction of voluntary muscles. Muscular spasms often

involve first the area of injury and infection and then the muscles of the jaw (trismus,

lockjaw), which contract so that the mouth cannot be opened. Gradually, other

voluntary muscles become involved, resulting in tonic spasms. Any external stimulus

6

may precipitate a tetanic generalized muscle spasm. The patient is fully conscious,

and pain may be intense. Death usually results from interference with the mechanics

of respiration. The mortality rate in generalized tetanus is very high.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis rests on the clinical picture and a history of injury, although only

50% of patients with tetanus have an injury for which they seek medical attention.

The primary differential diagnosis of tetanus is strychnine poisoning. Anaerobic

culture of tissues from contaminated wounds may yield C tetani, but neither

preventive nor therapeutic use of antitoxin should ever be withheld pending such

demonstration. Proof of isolation of C tetani must rest on production of toxin and its

neutralization by specific antitoxin.

Prevention & Treatment

The results of treatment of tetanus are not satisfactory. Therefore, prevention is all-

important. Prevention of tetanus depends upon (1) active immunization with toxoids;

(2) proper care of wounds contaminated with soil, etc; (3) prophylactic use of

antitoxin; and (4) administration of penicillin. The intramuscular administration of

250–500 units of human antitoxin (tetanus immune globulin) gives adequate systemic

protection (0.01 unit or more per milliliter of serum) for 2–4 weeks. It neutralizes the

toxin that has not been fixed to nervous tissue. Active immunization with tetanus

toxoid should accompany antitoxin prophylaxis.

Patients who develop symptoms of tetanus should receive muscle relaxants,

sedation, and assisted ventilation. Sometimes they are given very large doses of

antitoxin (3000–10,000 units of tetanus immune globulin) intravenously to neutralize

toxin that has not yet been bound to nervous tissue. Surgical debridement is vitally

important because it removes the necrotic tissue that is essential for proliferation of

the organisms. Hyperbaric oxygen has no proved effect.

Penicillin strongly inhibits the growth of C tetani and stops further toxin

production. Antibiotics may also control associated pyogenic infection. When a

previously immunized individual sustains a potentially dangerous wound, an

additional dose of toxoid should be injected to restimulate antitoxin production.

Control

Tetanus is a totally preventable disease. Universal active immunization with tetanus

toxoid should be mandatory. Three injections comprise the initial course of

immunization, followed by another dose about 1 year later. Initial immunization

should be carried out in all children during the first year of life. A "booster" injection

of toxoid is given upon entry into school. Thereafter, "boosters" can be spaced 10

years apart to maintain serum levels of more than 0.01 unit antitoxin per milliliter. In

young children, tetanus toxoid is often combined with diphtheria toxoid and pertussis

vaccine.

7

Clostridia that Produce Invasive Infections

Many different toxin-producing clostridia (Clostridium perfringens and related

clostridia) can produce invasive infection (including myonecrosis and gas gangrene)

if introduced into damaged tissue. About 30 species of clostridia may produce such an

effect, but the most common in invasive disease is Clostridium perfringens (90%).

Toxins

The invasive clostridia produce a large variety of toxins and enzymes that result in

a spreading infection. Many of these toxins have lethal, necrotizing, and hemolytic

properties. The alpha toxin of C perfringens type A is a lecithinase, and its lethal

action is proportionate to the rate at which it splits lecithin (an important constituent

of cell membranes) to phosphorylcholine and diglyceride. The theta toxin has similar

hemolytic and necrotizing effects but is not a lecithinase. DNase and hyaluronidase,

and collagenase that digests collagen of subcutaneous tissue and muscle, are also

produced.

Some strains of C perfringens produce a powerful enterotoxin, especially when

grown in meat dishes. When more than 10

8

vegetative cells are ingest and sporulate in

the gut, enterotoxin is formed. The enterotoxin is a protein (MW 35,000) that may be

a nonessential component of the spore coat; it is distinct from other clostridial toxins.

It induces intense diarrhea in 6–18 hours. The action of C perfringens enterotoxin

involves marked hyper-secretion in the jejunum and ileum, with loss of fluids and

electrolytes in diarrhea. Much less frequent symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and

fever. This illness is similar to that produced by B cereus and tends to be self-limited.

Pathogenesis

In invasive clostridial infections, spores reach tissue either by contamination of

traumatized areas (soil, feces) or from the intestinal tract. The spores germinate at low

oxidation-reduction potential; vegetative cells multiply, ferment carbohydrates present

in tissue, and produce gas. The distention of tissue and interference with blood supply,

together with the secretion of necrotizing toxin and hyaluronidase, favor the spread of

infection. Tissue necrosis extends, providing an opportunity for increased bacterial

growth, hemolytic anemia, and, ultimately, severe toxemia and death.

In gas gangrene (clostridial myonecrosis), a mixed infection is the rule. In addition

to the toxigenic clostridia, proteolytic clostridia and various cocci and gram-negative

organisms are also usually present. C perfringens occurs in the genital tract of 5% of

women. Clostridial bacteremia is a frequent occurrence in patients with neoplasms.

Also, C perfringens type C produces a necrotizing enteritis (pigbel) that can be highly

fatal in children. Immunization with type C toxoid appears to have preventive value.

8

Clinical Findings

From a contaminated wound (eg, a compound fracture, postpartum uterus), the

infection spreads in 1–3 days to produce crepitation in the subcutaneous tissue and

muscle, foul-smelling discharge, rapidly progressing necrosis, fever, hemolysis,

toxemia, shock, and death. Treatment is with early surgery (amputation) and antibiotic

administration. Until the advent of specific therapy, early amputation was the only

treatment.

Diagnostic Laboratory Tests

Specimens consist of material from wounds, pus, tissue. The presence of large

gram-positive rods in Gram-stained smears suggests gas gangrene clostridia; spores

are not regularly present.

Material is inoculated into chopped meat-glucose medium and thioglycolate

medium and onto blood agar plates incubated anaerobically. The growth from one of

the media is transferred into milk. A clot torn by gas in 24 hours is suggestive of C

perfringens. Once pure cultures have been obtained by selecting colonies from

anaerobically incubated blood plates, they are identified by biochemical reactions

(various sugars in thioglycolate, action on milk), hemolysis, and colony form.

Lecithinase activity is evaluated by the precipitate formed around colonies on egg

yolk media. Final identification rests on toxin production and neutralization by

specific antitoxin. C perfringens rarely produces spores when cultured on agar in the

laboratory.

Treatment

The most important aspect of treatment is prompt and extensive surgical

debridement of the involved area and excision of all devitalized tissue, in which the

organisms are prone to grow. Administration of antimicrobial drugs, particularly

penicillin, is begun at the same time. Hyperbaric oxygen may be of help in the

medical management of clostridial tissue infections. It is said to "detoxify" patients

rapidly.

Antitoxins are available against the toxins of C perfringens, Clostridium novyi,

Clostridium histolyticum, and Clostridium septicum, usually in the form of

concentrated immune globulins. Polyvalent antitoxin (containing antibodies to several

toxins) has been used. Although such antitoxin is sometimes administered to

individuals with contaminated wounds containing much devitalized tissue, there is no

evidence for its efficacy. Food poisoning due to C perfringens enterotoxin usually

requires only symptomatic care.

Prevention & Control

Early and adequate cleansing of contaminated wounds and surgical debridement,

together with the administration of antimicrobial drugs directed against clostridia (eg,

penicillin), are the best available preventive measures. Antitoxins should not be relied

on. Although toxoids for active immunization have been prepared, they have not

9

come into practical use.

Clostridium Difficile & Diarrheal Disease

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is diagnosed by detection of one or both C difficile

toxins in stool and by endoscopic observation of pseudomembranes or microabscesses

in patients who have diarrhea and have been given antibiotics. Plaques and

microabscesses may be localized to one area of the bowel. The diarrhea may be

watery or bloody, and the patient frequently has associated abdominal cramps,

leukocytosis, and fever. Although many antibiotics have been associated with

pseudomembranous colitis, the most common are ampicillin and clindamycin. The

disease is treated by discontinuing administration of the offending antibiotic and

orally giving either metronidazole or vancomycin.

Administration of antibiotics results in proliferation of drug-resistant C difficile that

produces two toxins. Toxin A, a potent enterotoxin that also has some cytotoxic

activity, binds to the brush border membranes of the gut at receptor sites. Toxin B is a

potent cytotoxin. Both toxins are found in the stools of patients with

pseudomembranous colitis. Not all strains of C difficile produce the toxins, and the

tox genes apparently are not carried on plasmids or phage.

Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea

The administration of antibiotics frequently leads to a mild to moderate form of

diarrhea, termed antibiotic-associated diarrhea. This disease is generally less severe

than the classic form of pseudomembranous colitis. As many as 25% of cases of

antibiotic-associated diarrhea may be associated with C difficile.