Dr. Faez Khalaf Abdulmuhsen

MBChB,FIBMS-CABMS(IM),MD-FACP(US), FIBMS

(GIT&HEP)

Subspecialist Gastroenterologist & Endoscopisit

Medical college ,Thi Qar U, Internal medicine department

Al Hussein Teaching Hospital –GIT Center

Member of Iraqi gastroenterology society

Hepatology lectures 2020

INFECTIONS AND THE LIVER

The liver may be subject to a number of different

infections. These include hepatotropic viral

infections, and bacterial and protozoal infections.

Each has specific clinical features and requires

targeted therapies.

Viral hepatitis

This must be considered in anyone presenting with

hepatitis liver blood tests (high transaminases).

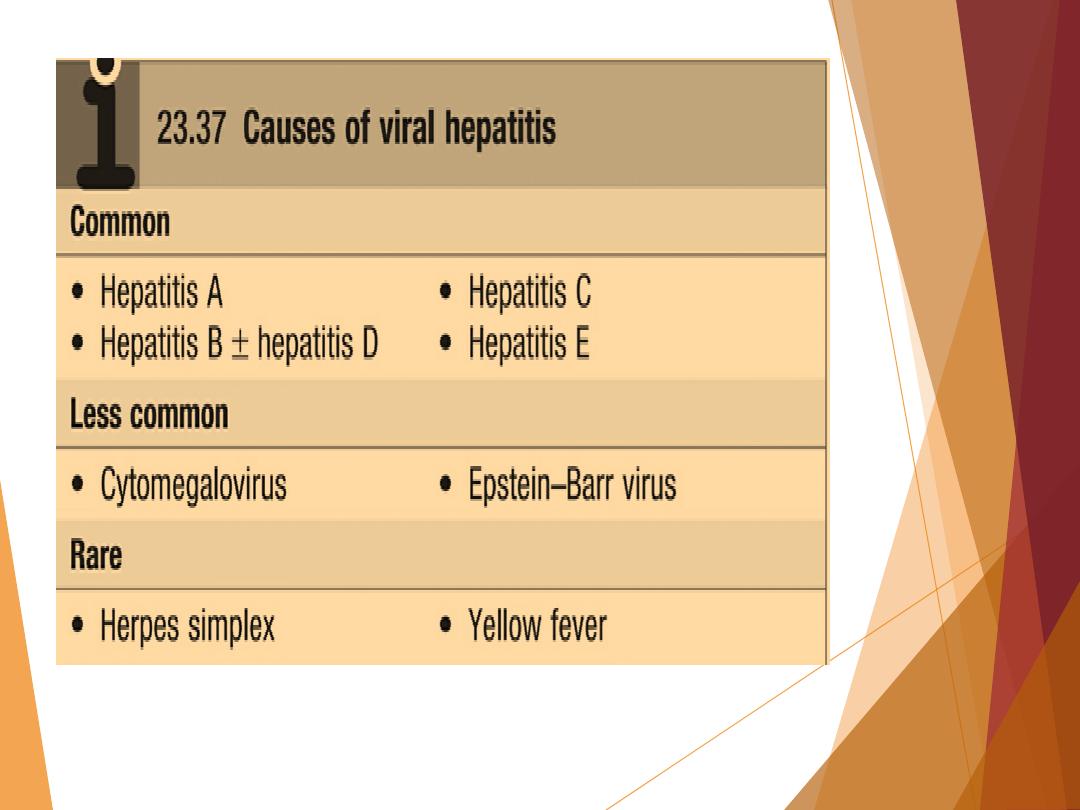

The causes are listed in Box 23.37.

All these viruses cause illnesses with similar clinical

and pathological features and which are frequently

anicteric or even asymptomatic.

They differ in their tendency to cause acute and

chronic infections.

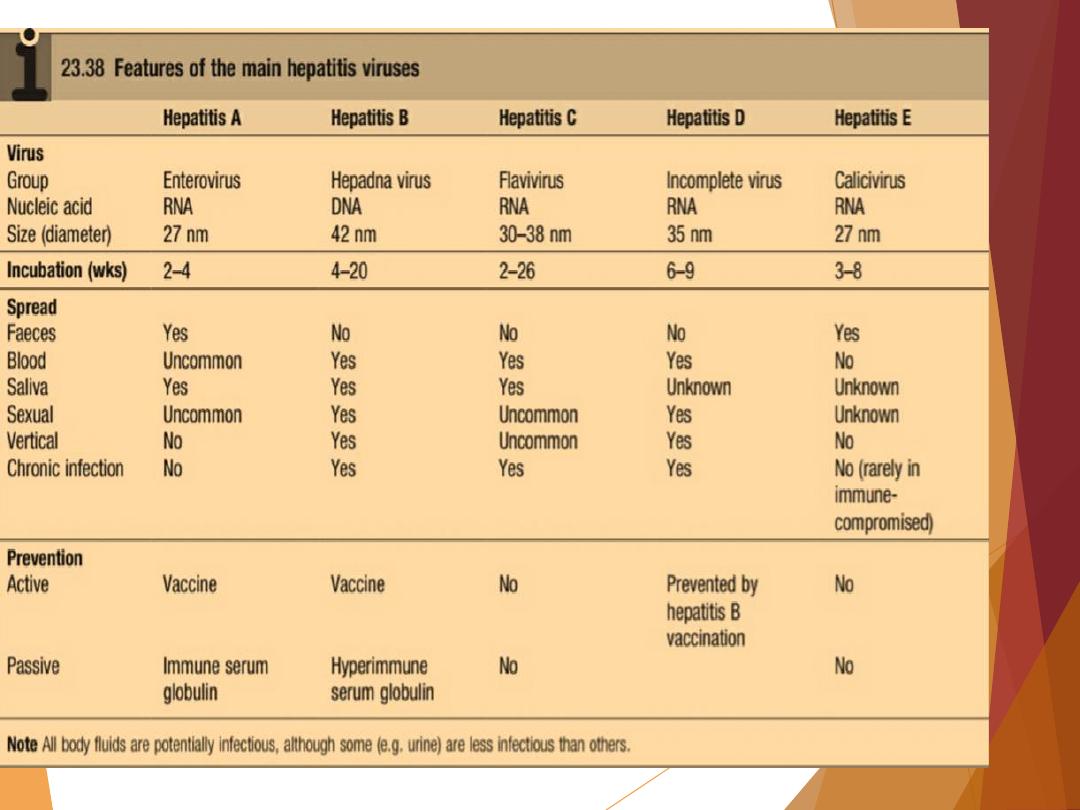

The features of the major hepatitis viruses are shown

in Box 23.38.

Clinical features of acute

infection

A non-specific prodromal illness characterised by headache, myalgia, arthralgia,

nausea and anorexia usually precedes the development of jaundice by a few

days to 2 weeks.

Vomiting and diarrhoea may follow, and abdominal discomfort is common.

Dark urine and pale stools may precede jaundice.

There are usually few physical signs.

The liver is often tender but only minimally enlarged.

Occasionally, mild splenomegaly and cervical lymphadenopathy are seen.

These are more frequent in children or those with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

infection. Symptoms rarely last longer than 3–6 weeks. Complications may

occur but are rare.

1- Acute liver failure 2-Cholestatic hepatitis (hepatitis A)

3- Aplastic anemia 4- Chronic liver disease

5.cirrhosis (hepatitis B and C) 6• Relapsing hepatitis

Investigations:

A hepatitic pattern of LFTs develops, with serum

transaminases typically between 200 and 2000 U/L in an

acute infection (usually lower and fluctuating in chronic

infections).

The plasma bilirubin reflects the degree of liver damage.

The ALP rarely exceeds twice the upper limit of normal.

Prolongation of the PT indicates the severity of the

hepatitis but rarely exceeds 25 seconds, except in rare

cases of acute liver failure.

The white cell count is usually normal with a relative

lymphocytosis. Serological tests confirm the aetiology of

the infection.

Management in general

1.

Most individuals do not need hospital care.

2.

Drugs such as sedatives and narcotics, which are

metabolised in the liver, should be avoided.

3.

No specific dietary modifications are needed.

4.

Alcohol should be avoided during the acute illness.

5.

Elective surgery should be avoided in cases of acute viral

hepatitis (a risk of post-operative liver failure).

6.

Liver transplantation is very rarely indicated for acute

viral hepatitis complicated by liver failure.

Hepatitis A

(HAV) belongs to the picornavirus group of enteroviruses. HAV is

highly infectious and is spread by the

faecal–oral

route.

Infected individuals, who may be asymptomatic, excrete the

virus in faeces for about 2–3 weeks before the onset of

symptoms and then for a further 2 weeks or so

.

Infection is common in children but often asymptomatic

, and so

up to 30% of adults will have serological evidence of past

infection

but give no history of jaundice.

Infection is also more common in areas of overcrowding and

poor sanitation.

In occasional outbreaks, water and shellfish have been the

vehicles of transmission. A chronic carrier state does not occur.

Investigations: Only one HAV antigen has been found and infected

people make an antibody to this antigen (anti-HAV

).

Anti-HAV is important in diagnosis

, as HAV is only present in the blood

transiently during the incubation period.

Excretion in the stools occurs for only 7–14 days after the onset of the

clinical illness and the virus cannot be grown readily

.

Anti-HAV of the IgM type, indicating a primary immune response

, is

already present in the blood at the onset of the clinical illness and is

diagnostic of an acute HAV infection.

Titres of this antibody fall to low levels within about 3 months of

recovery

.

Anti-HAV of the IgG type is of no diagnostic value

, as HAV infection is

common and this antibody persists for years after infection, but it

can

be used as a marker of previous HAV

infection. Its presence indicates

immunity to HAV.

Management: Infection in the community is

best prevented by improving

social conditions

, especially overcrowding and poor sanitation.

Individuals can be given substantial protection from infection by active

immunisation with an inactivated virus vaccine.

Immunisation should be considered for individuals with chronic hepatitis B or

C infections

.

Immediate protection can be provided by immune serum globulin if this is

given soon after exposure to the virus.

The protective effect of immune serum globulin is attributed to its anti-HAV

content.

Immunisation should be considered for those at particular risk:

1- close contacts of HAV-infected patients .

2-The elderly, those with other major disease .

3-Pregnant women.

4-People travelling to endemic areas are best protected by vaccination

Immune serum globulin can be effective in an outbreak of

hepatitis, in a school or nursery, as injection of those at risk

prevents secondary spread to families.

Acute liver failure is rare in hepatitis A

(0.1%) and chronic

infection does not occur

.

However, HAV infection in patients with chronic liver

disease may cause serious or life-threatening disease. In

adults,

a cholestatic phase

with elevated ALP levels may

complicate infection.

There is no role for antiviral drugs in the therapy of HAV

infection.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is caused by an RNA virus that is

endemic in India and the Middle East. An increase

in prevalence has recently been noted in northern

Europe and infection is no longer seen only in

travellers from an endemic area.

The clinical presentation and management of

hepatitis E are similar to that of hepatitis A.

Disease is spread via the faecal–oral route; in most

cases, it presents as a self-limiting acute hepatitis

and does not usually cause chronic liver disease,

although some cases have been described, usually

in immunocompromised patients. Hepatitis E

differs from hepatitis A in that infection during

pregnancy is associated with the development of

acute liver failure, which has a high mortality. In

acute infection, IgM antibodies to HEV are positive.

Hepatitis B

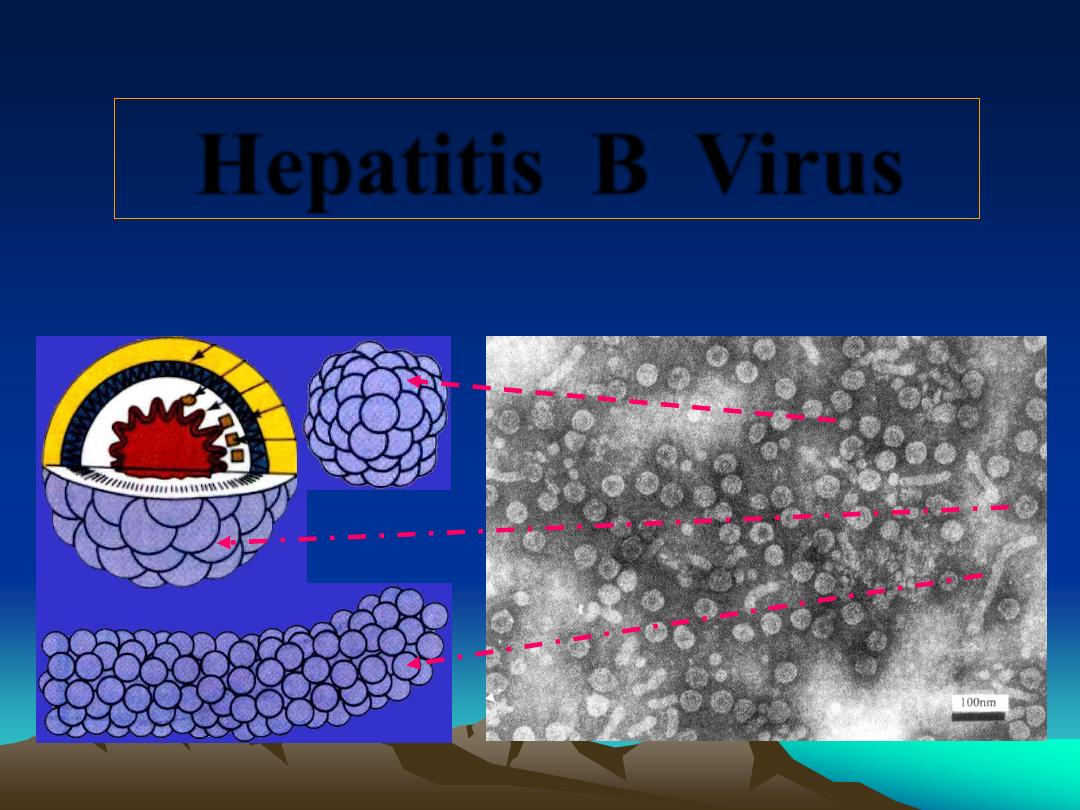

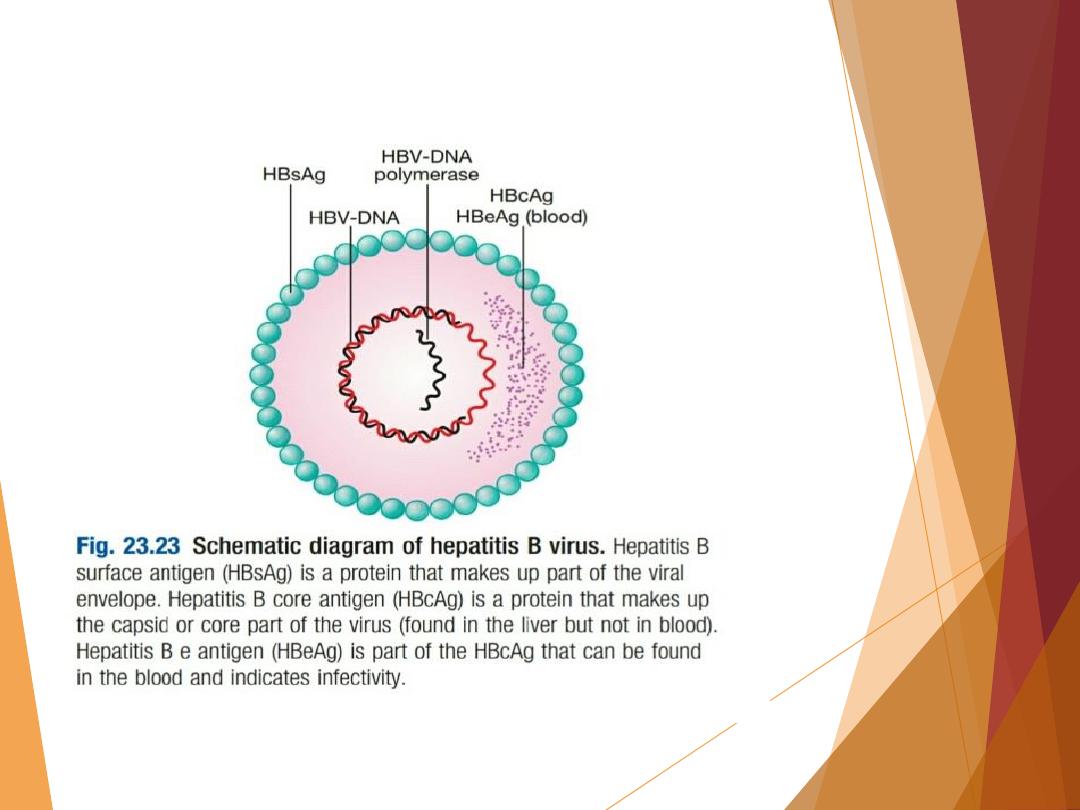

The HBV consists of a core containing DNA and a DNA polymerase

enzyme needed for virus replication. The core of the virus is

surrounded by surface protein (Fig. 23.23).

The virus, also called a Dane particle, and an excess of its surface

protein (known as hepatitis B surface antigen) circulate in the

blood.

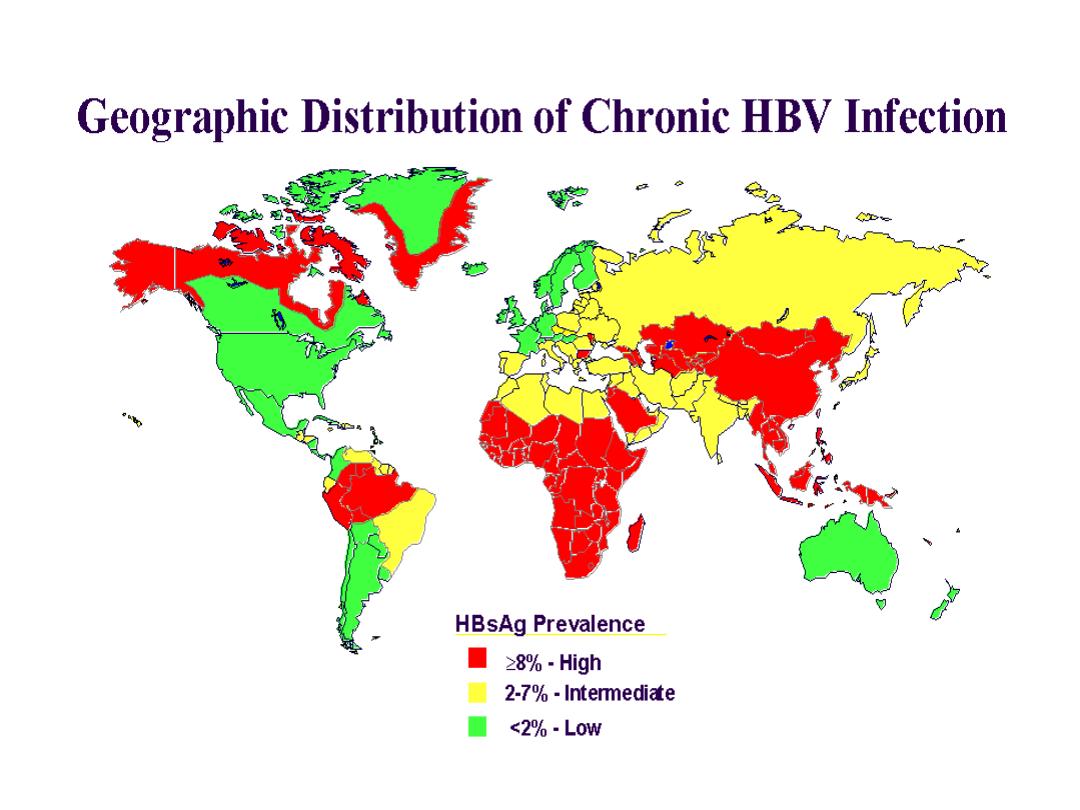

Humans are the only source of infection

. Hepatitis B is one of the

most common causes of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular

carcinoma

worldwide. Approximately one-third of the world’s

population have serological evidence of past or current infection

with hepatitis B and approximately

350–400 million people are

chronic HBsAg carriers

.

Hepatitis B Virus

Hepatitis B may cause an acute viral hepatitis; however, acute

infection is

often asymptomatic

, particularly when acquired at

birth. Many individuals with chronic hepatitis B are also

asymptomatic.

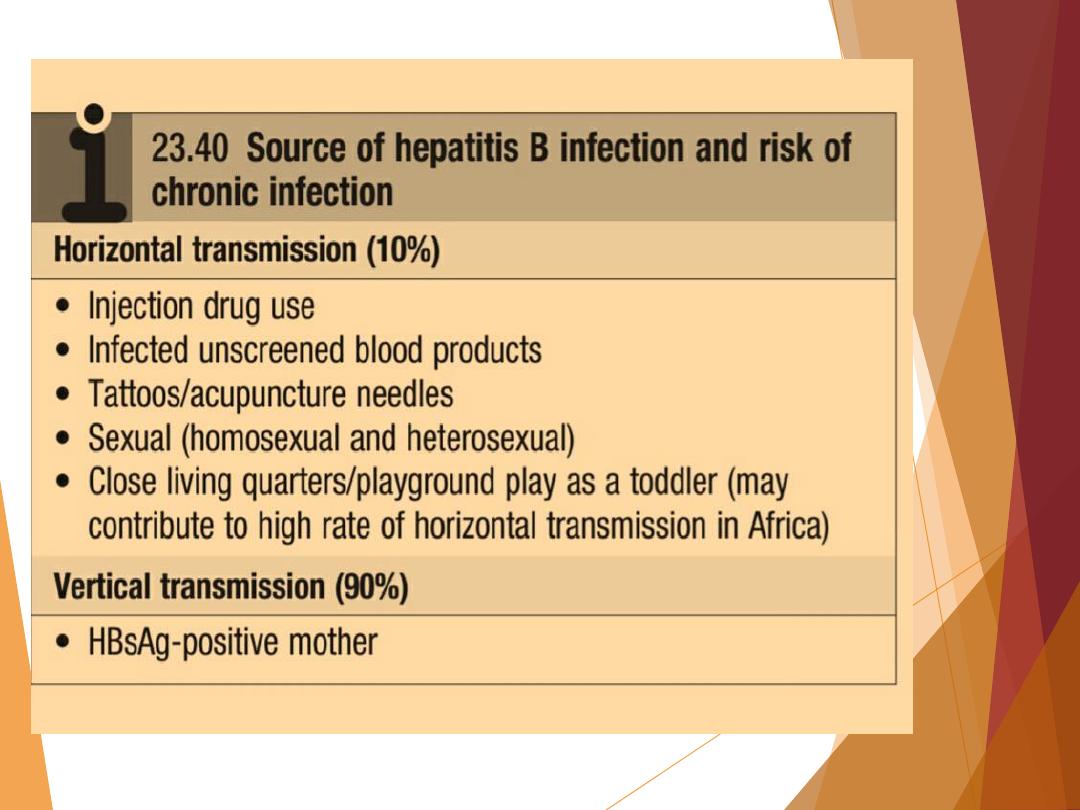

The risk of progression to chronic liver disease depends on the

source and timing of infection (Box 23.40). Vertical transmission

from mother to child in the perinatal period is the most common

cause of infection worldwide and carries the highest risk of

ongoing chronic infection.

In this setting, adaptive immune responses to HBV may be absent

initially, with apparent immunological tolerance. Several

mechanisms contribute towards this.

1-Firstly, the introduction of antigen in the neonatal period is

tolerogenic.

2-Secondly, the presentation of such antigen within the liver, as

described above, promotes tolerance; this is particularly evident

in the absence of a significant innate or inflammatory response.

3-Finally, very high loads of antigen may lead to so-called

‘exhaustion’ of cellular immune responses. However, the state of

tolerance is not permanent and may be reversed as a result of

therapy, or through spontaneous changes in innate responses

such as interferon-alpha and NK cells, accompanied by host-

mediated immunopathology.

High

Moderate

Low/Not

Detectable

blood

semen

urine

serum

vaginal fluid

feces

wound exudates

saliva

sweat

tears

breastmilk

Concentration of Hepatitis B Virus

in Various Body Fluids

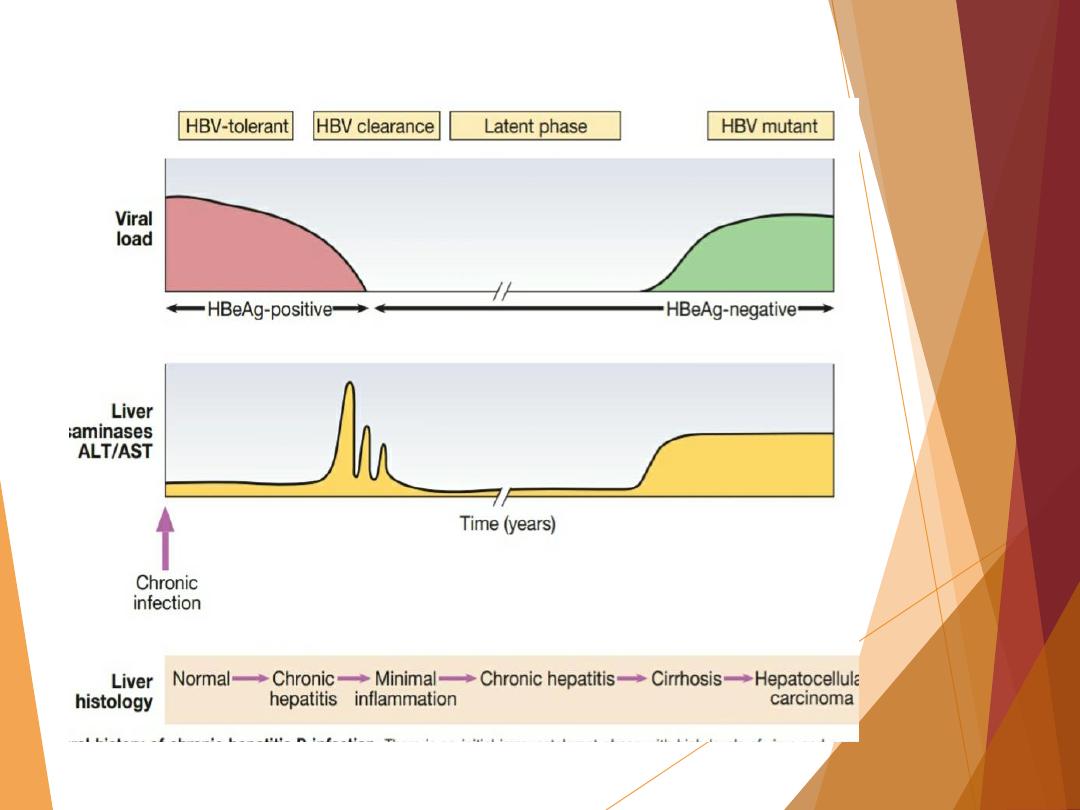

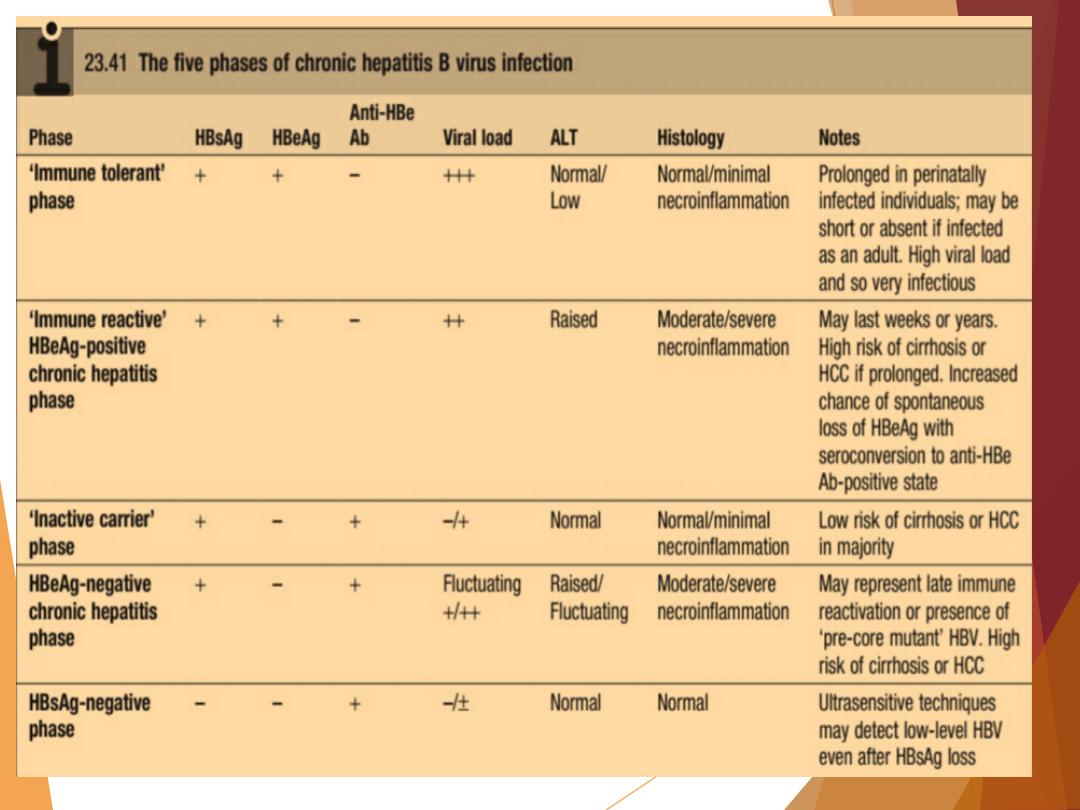

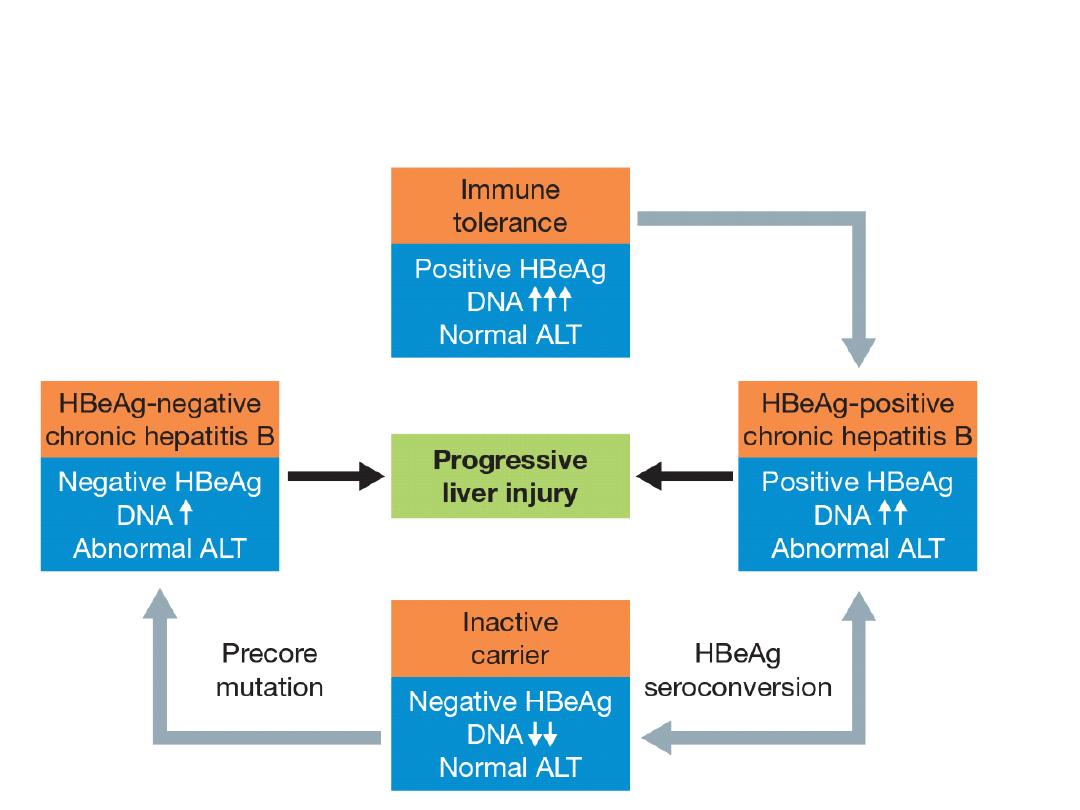

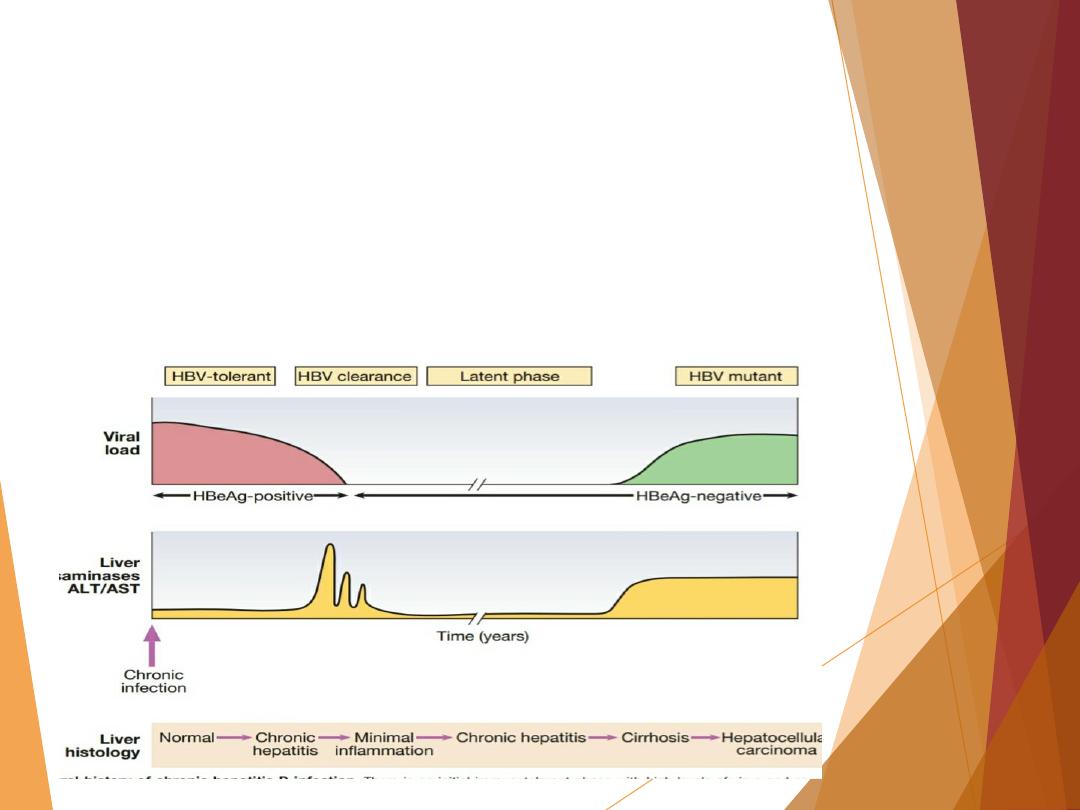

Chronic hepatitis can lead to cirrhosis or HCC, usually after

decades of infection (Fig. 23.24).

Chronic HBV infection is a dynamic process that can be

divided into five phases (Box 23.41); however, these are not

necessarily sequential and not all patients will go through

all phases.

It should be remembered that the virus is not directly

cytotoxic to cells; rather it is an immune response to viral

antigens

displayed on infected hepatocytes that initiates

liver injury.

This explains why there may be very high levels of viral

replication but little hepatocellular damage during the

‘immune tolerant’ phase.

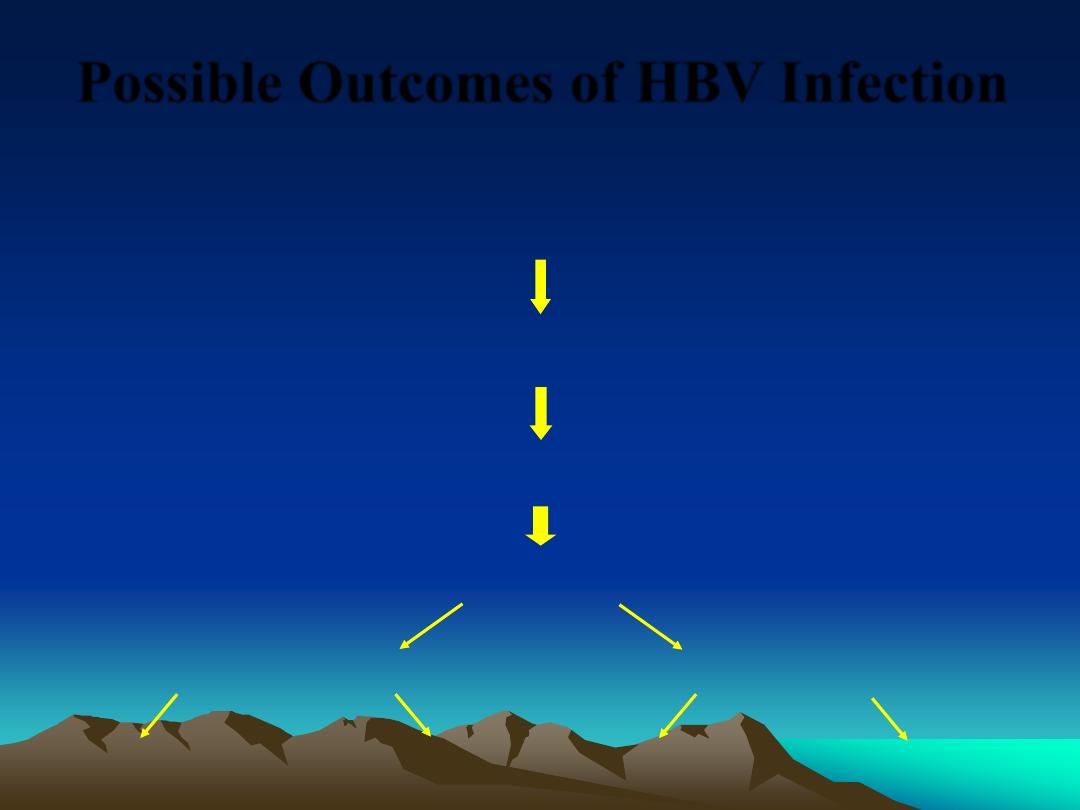

Possible Outcomes of HBV Infection

Acute

hepatitis B infection

Chronic

HBV infection

3-5% of adult-

acquired infections

95% of infant-

acquired infections

Cirrhosis

Chronic hepatitis

12-25% in 5 years

Liver failure

Hepatocellular

carcinoma

Liver transplant

6-15% in 5 years

20-23% in 5 years

Death

Death

Natural history of chronic hepatitis B

HBeAg positive

HBeAg Negative

Chronic infection

Chronic hepatitis

Chronic infection

Chronic hepatitis

HBsAg

High

High/intermediate

Low

Intermediate

HBeAg

Positive

Positive

Negative

Negative

HBV DNA

>104 IU/ml

104-107 IU/ml

<2,000 IU/ml°°

>2,000 IU/ml

ALT

Normal

Elevated

Normal

Elevated*

Liver disease

Normal

Moderate/severe

None

Moderate/severe

Old terminology

Immune tolerant

Immune reactive

Hbe Ag positive

Inactive carrier

Hbe Ag negative chronic

hepatitis

Fig. 1. Natural history and assessment of patients with chronic HBV infection based upon HBV and liver disease markers. *Persistently or intermittently. HBV DNA

levels can be between 2,000 and 20,000 IU/ml in some patients without sings of chronic hepatitis.

Investigations

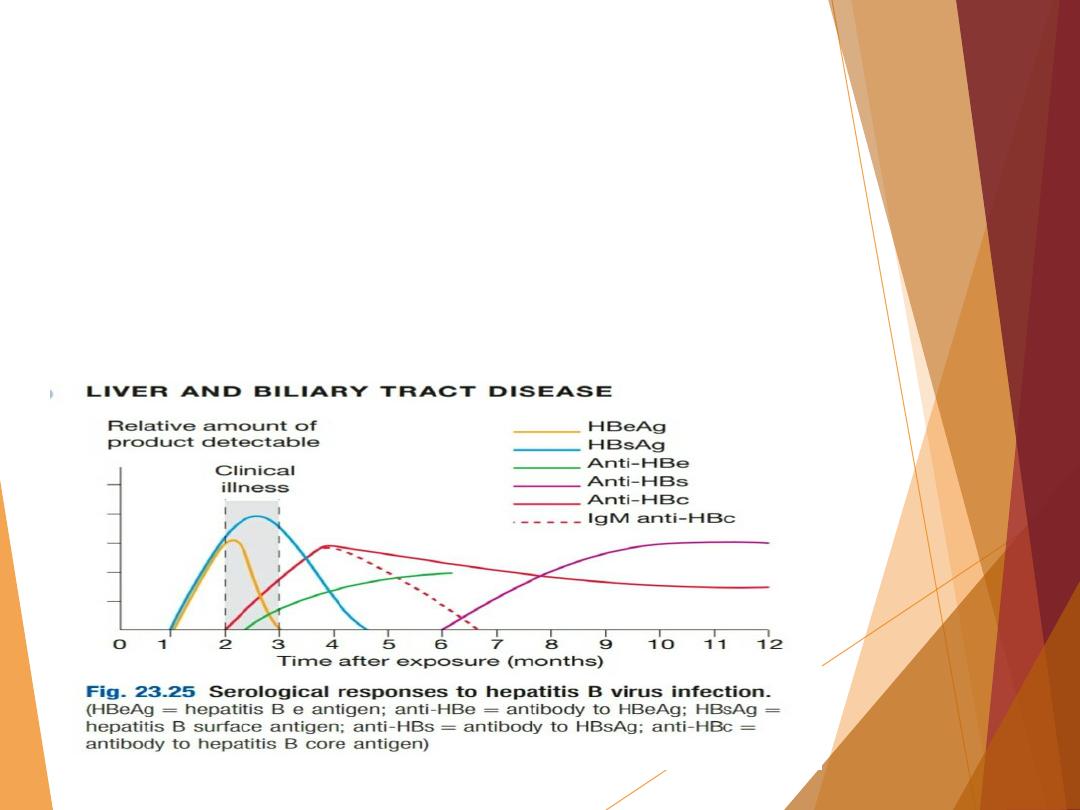

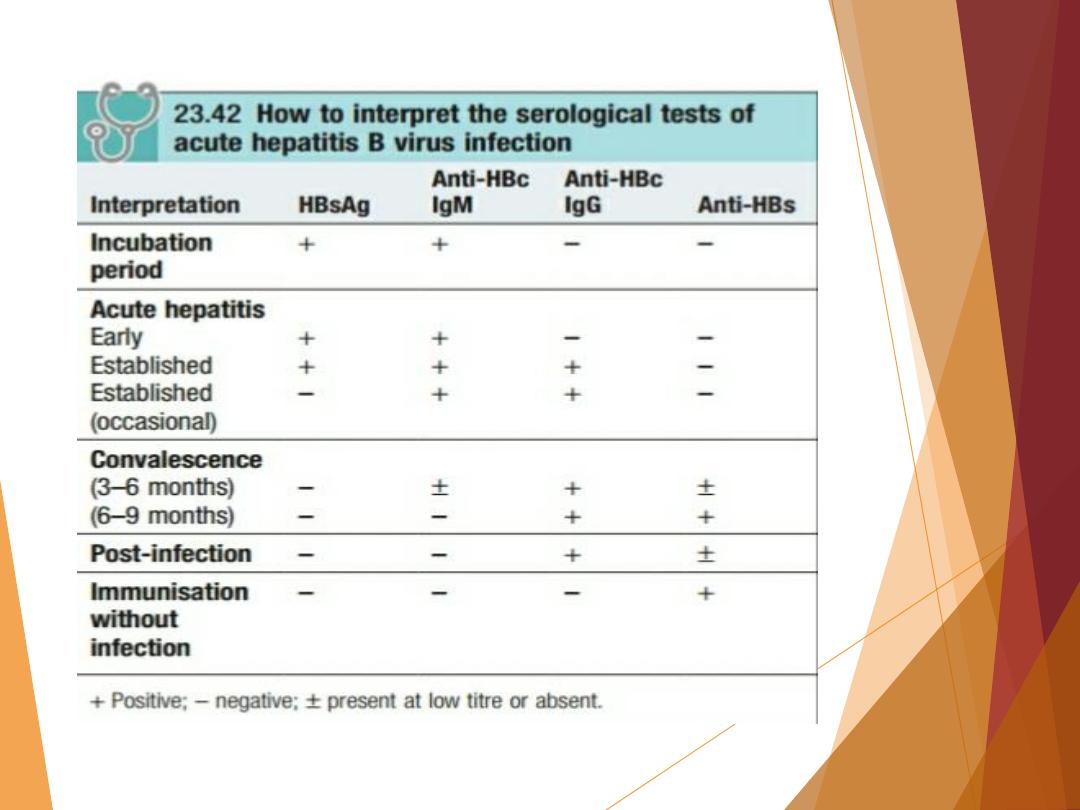

a)Serology

HBV contains several antigens to which infected persons

can make immune responses.

These antigens and their antibodies are important in

identifying HBV infection (Boxes 23.41 and 23.42), although

the widespread availability of polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) techniques to measure viral DNA levels in peripheral

blood means that longitudinal monitoring is now also

frequently guided by direct assessment of viral load.

1)

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

. HBsAg is an indicator of

active infection,

and a negative test for HBsAg makes HBV

infection very unlikely

. In acute liver failure from hepatitis B, the

liver damage is mediated by viral clearance and so HBsAg is

negative, with evidence of recent infection shown by the

presence of hepatitis B core IgM. HBsAg appears in the blood late

in the incubation period, but before the prodromal phase of acute

type B hepatitis; it may be present for a few days only,

disappearing even before jaundice has developed, but

usually

lasts for 3–4 weeks and can persist for up to 5 months

.

The persistence of HBsAg for longer than 6 months indicates

chronic infection.

Antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) usually appears after about 3–6

months and persists for many years or perhaps permanently. Anti-

HBs implies either a previous infection, in which case anti-HBc. is

usually also present, or previous vaccination, in which case anti-

HBc is not present.

2)Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). HBsAg is not found in the

blood, but antibody to

it (anti-HBc)

appears early in the illness and

rapidly reaches a high titre, which subsides gradually but then

persists. Anti-HBc is initially of IgM type, with IgG antibody

appearing later.

Anti-HBc (IgM) can sometimes reveal an acute

HBV infection when the HBsAg has disappeared and before anti-

HBs has developed

(see Fig. 23.25 and Box 23.42).

3)Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). HBeAg is an indicator of viral

replication. In acute hepatitis B it may appear only transiently at

the outset of the illness; its appearance is followed by the

production of antibody (anti-HBe). The

HBeAg reflects active

replication of the virus in the liver

. Chronic HBV infection is

marked by the presence of HBsAg and anti-HBc (IgG) in the blood.

Usually, HBeAg or anti-HBe is also present; HBeAg indicates

continued active replication of the virus in the liver.

The absence

of HBeAg usually implies low viral replication

;

the exception is

HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (also called ‘pre-core mutant’

infection

, in which high levels of viral replication, serum HBV-DNA

and hepatic necroinflammation are seen, despite negative HBeAg.

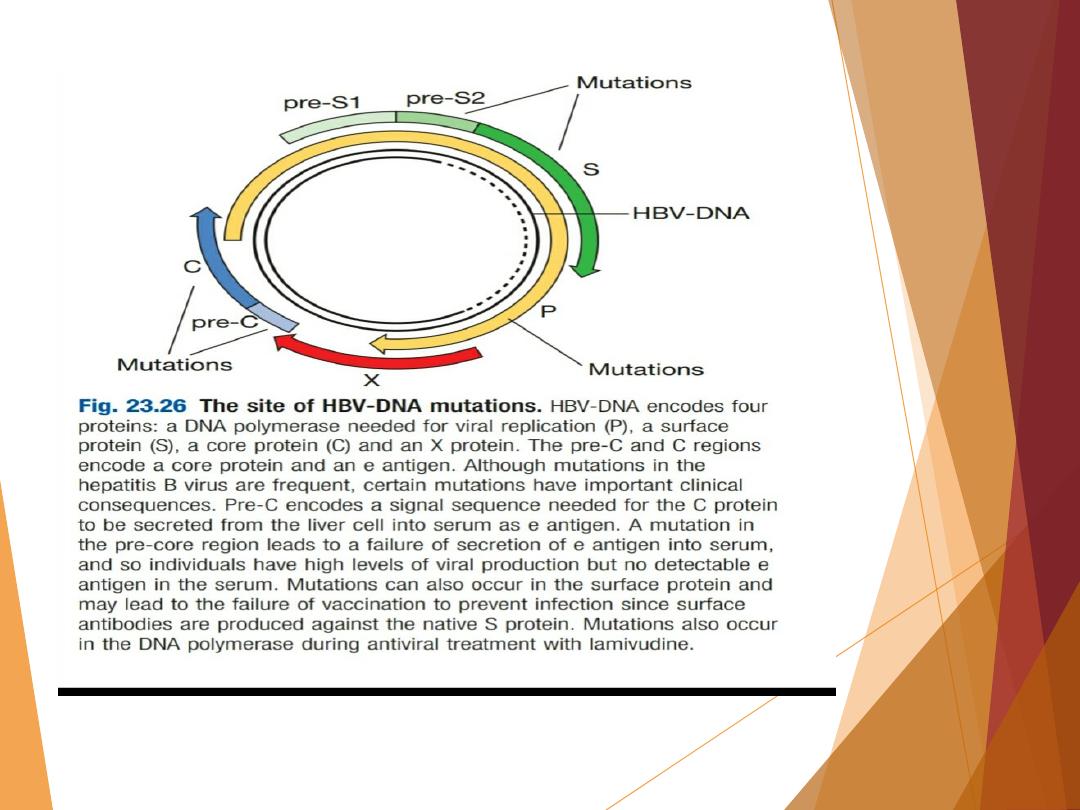

b) Viral load and genotype

HBV-DNA can be measured by PCR in the blood. Viral loads are

usually in excess of 10

5

copies/mL in the presence of active viral

replication, as indicated by the presence of e antigen.

In contrast, in those with low viral replication, HBsAg- and anti-

HBe-positive, viral loads are less than 10

5

copies/mL. The

exception is in patients who have a mutation in the pre-core

protein, which means they cannot secrete e antigen into serum

(Fig. 23.26). Such individuals will be anti-HBe-positive but have a

high viral load and often evidence of chronic hepatitis.

These mutations are common in the Far East, and those patients

affected are classified as having e antigen-negative chronic

hepatitis.

They respond differently to antiviral drugs from those with

classical e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis.

Measurement of viral load is important in monitoring antiviral

therapy and identifying patients with pre-core mutants. Specific

HBV genotypes (A–H)

can also be identified using PCR.

In some settings these may be useful in guiding therapy, as

genotype A tends to respond better to pegylated interferon alfa,

compared to genotypes C and D.

Management of acute hepatitis B

Treatment is supportive

, with monitoring for acute liver failure,

which occurs in less than 1% of cases.

There is no definitive evidence that antiviral therapy reduces the

severity or duration of acute hepatitis B.

Full recovery occurs in 90–95% of adults following acute HBV

infection

.

The remaining 5–10% develop a chronic hepatitis B infection that

usually continues for life

,

although later recovery occasionally

occurs

.

Infection passing from mother to child at birth leads to chronic

infection in the child in

90% of cases

and

recovery is rare

. Chronic

infection is also common in immunodeficient individuals, such as

those with Down’s syndrome or human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection. Fulminant liver failure due to acute hepatitis B

occurs in less than 1% of cases.

Recovery from acute HBV infection occurs within 6 months and is

characterised by the appearance of antibody to viral antigens.

Persistence of HBeAg beyond this time indicates chronic

infection.

Combined HBV and HDV infection causes more

aggressive disease.

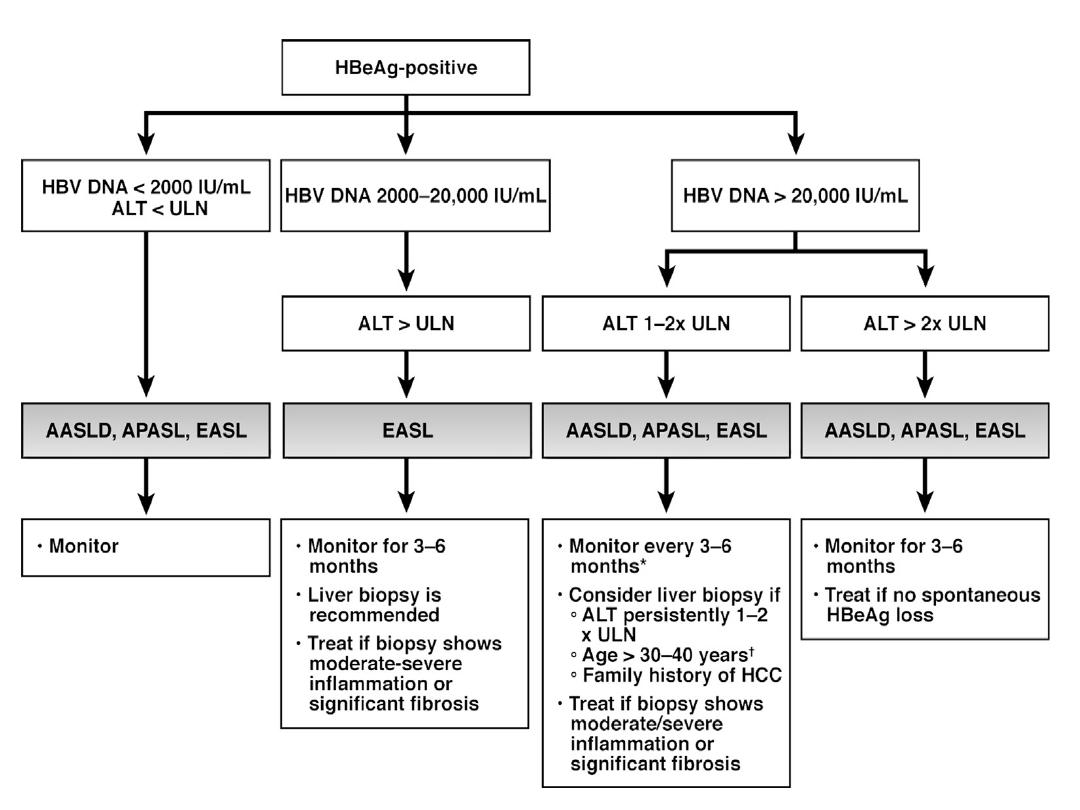

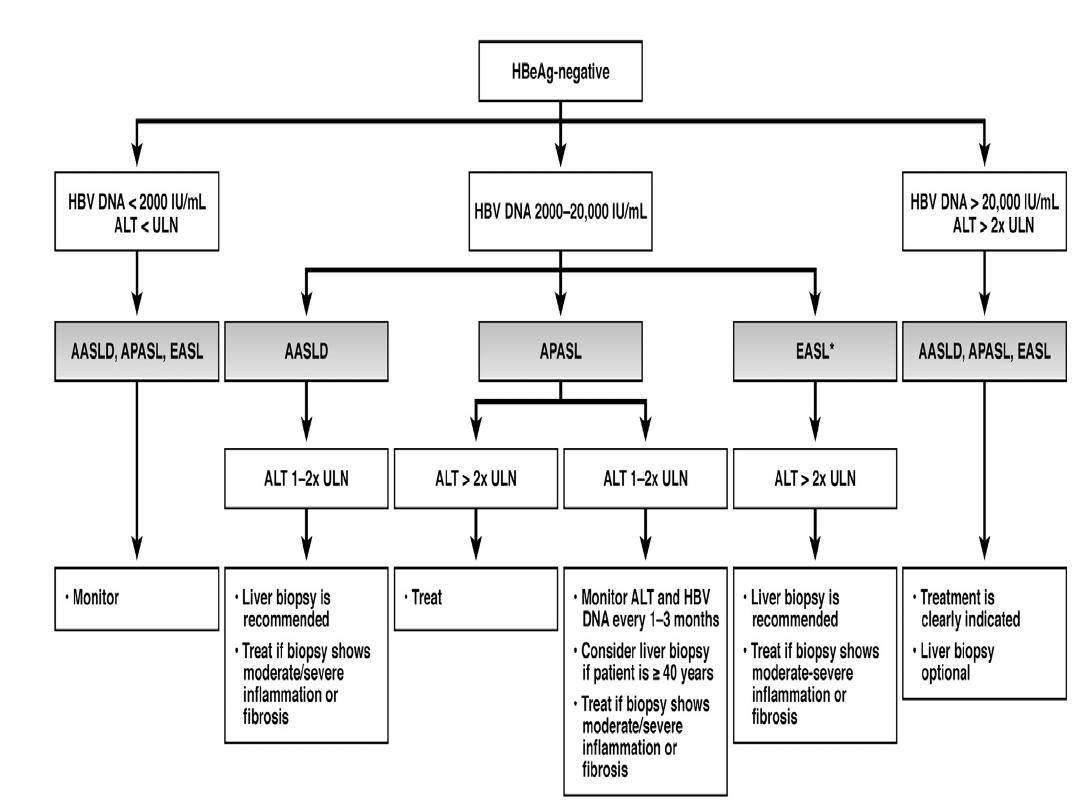

Management of chronic hepatitis B

Treatments are still limited, as no drug is consistently able to

eradicate hepatitis B infection completely (i.e. render the patient

HBsAg-negative).

T

he goals of treatment are HBeAg seroconversion, reduction in

HBV-DNA and normalisation of the LFTs

.

The indication for treatment is a high viral load in the presence

of active hepatitis, as demonstrated by elevated serum

transaminases and/or histological evidence of inflammation and

fibrosis.

The oral antiviral agents are more effective in reducing viral loads

in patients with

e antigen-negative

chronic hepatitis B than in

those with

e antigen-positive

chronic hepatitis B, as the pre-

treatment viral loads are lower.

Most patients with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic and

develop complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular

carcinoma only after many years (see Fig. 23.24). Cirrhosis

develops in 15–20% of patients with chronic HBV over 5–20 years

.

This proportion is higher in those who are e antigen-positive.

Two different types of drug are used to treat

hepatitis B: direct-acting nucleoside/nucleotide

analogues and pegylated interferon-alfa

.

*Direct-acting nucleoside/nucleotide antiviral agents

Orally administered nucleoside/nucleotide antiviral agents are the

mainstay of therapy. These act by inhibiting the

reverse

transcription of pre-genomic RNA to HBV-DNA by HBV-DNA

polymerase but do not directly affect the cccDNA (covalently

closed circular DNA) template for viral replication

,

and so relapse

is common if treatment is withdrawn

. One major concern is the

selection of antiviral-resistant mutations with long-term

treatment. This is particularly important with some of the older

agents, such as lamivudine, as mutations induced by previous

antiviral exposure may also induce resistance to newer agents.

Entecavir and tenofovir are potent antivirals with a high barrier to

genetic resistance, and so are the most appropriate first-line

agents.

1. Lamivudine. Although effective, long-term therapy is often

complicated by the development of HBV-DNA polymerase

mutants (e.g. the ‘YMDD variant’), which may occur after 9

months and are characterised by a rise in viral load during

treatment.

2. Telbivudine is more potent but is also susceptible to viral

resistance.

3. Adefovir is associated with development of HBV-DNA mutants

at a lower rate than with lamivudine; 2% are identified after 2

years of treatment but this figure increases to

18% after 3 years.

4. Entecavir and 5.tenofovir. Monotherapy with entecavir or

tenofovir is more effective than either lamivudine or adefovir in

reducing viral load in HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic

hepatitis. Antiviral resistance mutations occur in

only 1–2% after 3

years

of entecavir drug exposure. Both drugs have anti-HIV action

and so their use as monotherapy is contraindicated in HIV-positive

patients, as it may lead to HIV antiviral drug resistance.

*

Interferon-alfa: this

is most effective in patients with

a low viral load and serum transaminases greater than twice the

upper limit of normal, in whom it acts

by augmenting a native

immune response

.

In HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis, 33% lose e antigen after 4–6

months of treatment, compared to 12% of controls

. Response

rates are lower in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, even when

patients are given longer courses of treatment.

Interferon is contraindicated in the presence of cirrhosis

, as it may

cause a rise in serum transaminases and precipitate liver failure.

Longer-acting pegylated interferons that can be given once

weekly have been evaluated in both HBeAgpositive and HBeAg-

negative chronic hepatitis.

Side-effects are common and include fatigue, depression,

irritability, bone marrow suppression and the triggering of

autoimmune thyroid disease.

Liver transplantation

Historically, liver transplantation was contraindicated in

hepatitis B because infection often recurred in the graft.

However, the use of post-liver transplant prophylaxis with

direct-acting antiviral agents and hepatitis B

immunoglobulins has reduced the re-infection rate to 10%

and increased 5-year survival to 80%, making

transplantation an acceptable treatment option.

Prevention:

Individuals are most infectious when markers of continuing

viral replication, such

as HBeAg, and high levels of HBV

-

DNA are present in the blood.

HBV-DNA can be found in

saliva, urine, semen and vaginal

secretions

.

The virus is about ten times more infectious than hepatitis

C, which in turn is about ten times more infectious than

HIV

.

A recombinant hepatitis B vaccine containing HBsAg is available

(Engerix

) and is capable of producing active immunisation

in 95%

of normal individuals

. The vaccine should be offered to those at

special risk of infection who are not already immune, as

evidenced by anti-HBs in the blood (Box 23.46). The vaccine is

ineffective in those already infected by HBV. Infection can also be

prevented or minimised by the intramuscular injection of

hyperimmune serum globulin prepared from blood containing

anti-HBs. This should be given within 24 hours, or at most a week,

of exposure to infected blood in circumstances likely to cause

infection (e.g. needlestick injury, contamination of cuts or mucous

membranes).

Vaccine can be given together with hyperimmune globulin

(active–passive immunisation). Neonates born to hepatitis B-

infected mothers should be immunised at birth and given

immunoglobulin. Hepatitis B serology should then be checked at

12 months of age.

At-risk groups meriting hepatitis B Vaccination in low-

endemic areas

Parenteral drug users

Men who have sex with men

Close contacts of infected individuals

Newborn of infected mothers

Regular sexual partners

Patients on chronic hemodialysis

Patients with chronic liver disease

Medical, nursing and laboratory personnel

Hepatitis D (Delta virus)

The hepatitis D virus (HDV) is an RNA-defective virus that has no

independent existence; it requires HBV for replication and has the

same sources and modes of spread. It can infect individuals

simultaneously with HBV, or can superinfect those who are

already chronic carriers of HBV. Simultaneous infections give rise

to acute hepatitis, which is often severe but is limited by recovery

from the HBV infection. Infections in individuals who are chronic

carriers of HBV can cause acute hepatitis with spontaneous

recovery, and occasionally simultaneous cessation of the chronic

HBV infection occurs. Chronic infection with HBV and HDV can

also occur, and this frequently causes rapidly progressive chronic

hepatitis and eventually cirrhosis. HDV has a worldwide

distribution. It is endemic in parts of the Mediterranean basin,

Africa and South America, where transmission is mainly by close

personal contact and occasionally by vertical transmission from

mothers who also carry HBV. In non-endemic areas, transmission

is mainly a consequence of parenteral drug misuse.

Investigations

: HDV contains a single antigen to which

infected individuals make an antibody (anti-HDV). Delta

antigen appears in the blood only transiently, and in

practice diagnosis depends on detecting anti-HDV.

Simultaneous infection with HBV and HDV followed by full

recovery is associated with the appearance of low titres of

anti-HDV of IgM type within a few days of the onset of the

illness. This antibody generally disappears within 2 months

but persists in a few patients. Superinfection of patients

with chronic HBV infection leads to the production of high

titres of anti-HDV, initially IgM and later IgG. Such patients

may then develop chronic infection with both viruses, in

which case anti-HDV titres plateau at high levels.

Management

: Effective management of hepatitis B

prevents hepatitis D.

Other forms of viral hepatitis

Non-A, non-B, non-C (NANBNC) or non-A–E hepatitis is the

term used to describe hepatitis thought to be due to a virus

that is not HAV, HBV, HCV or HEV. Other viruses that affect

the liver probably exist, but the viruses described above

now account for the majority of hepatitis virus infections.

Cytomegalovirus and EBV infection cause abnormal LFTs in

most patients, and occasionally jaundice occurs. Herpes

simplex is a rare cause of hepatitis in adults, and most of

these patients are immunocompromised. Abnormal LFTs

are also common in chickenpox, measles, rubella and acute

HIV infection.

HIV infection and the liver:

Several causes of abnormal LFTs occur in HIV infection:

Hepatitic blood tests

• Chronic hepatitis C

• Chronic hepatitis B

• Antiretroviral drugs

• Cytomegalovirus

Cholestatic blood tests

• Tuberculosis

• Atypical mycobacterium

• Sclerosing cholangitis due to cryptosporidia