P a g e | 1 GU-TB G:E

GENITOURINARY TUBERCULOSIS

Genitourinary tuberculosis (GUTB) is a common site of extrapulmonary TB.

(15-20% of extrapulmonary cases of TB.). It may involve the kidneys, ureter,

bladder, or genital organs.

Clinical symptoms usually develop 10-15 years after the primary infection.

Age: The most common age at presentation is 30-45 years.

Sex: Male-to-female ratio is 5:3.

Only about a quarter of patients with GUTB have a known history of TB; about

half of these patients have normal chest radiography findings.

Causative Agents:

- The most common pathogen is M tuberculosis.

- Uncommonly implicated pathogens include the following:

Mycobacterium kansasii

Mycobacterium fortuitum

Mycobacterium bovis

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare

Mycobacterium xenopi

Mycobacterium celatum

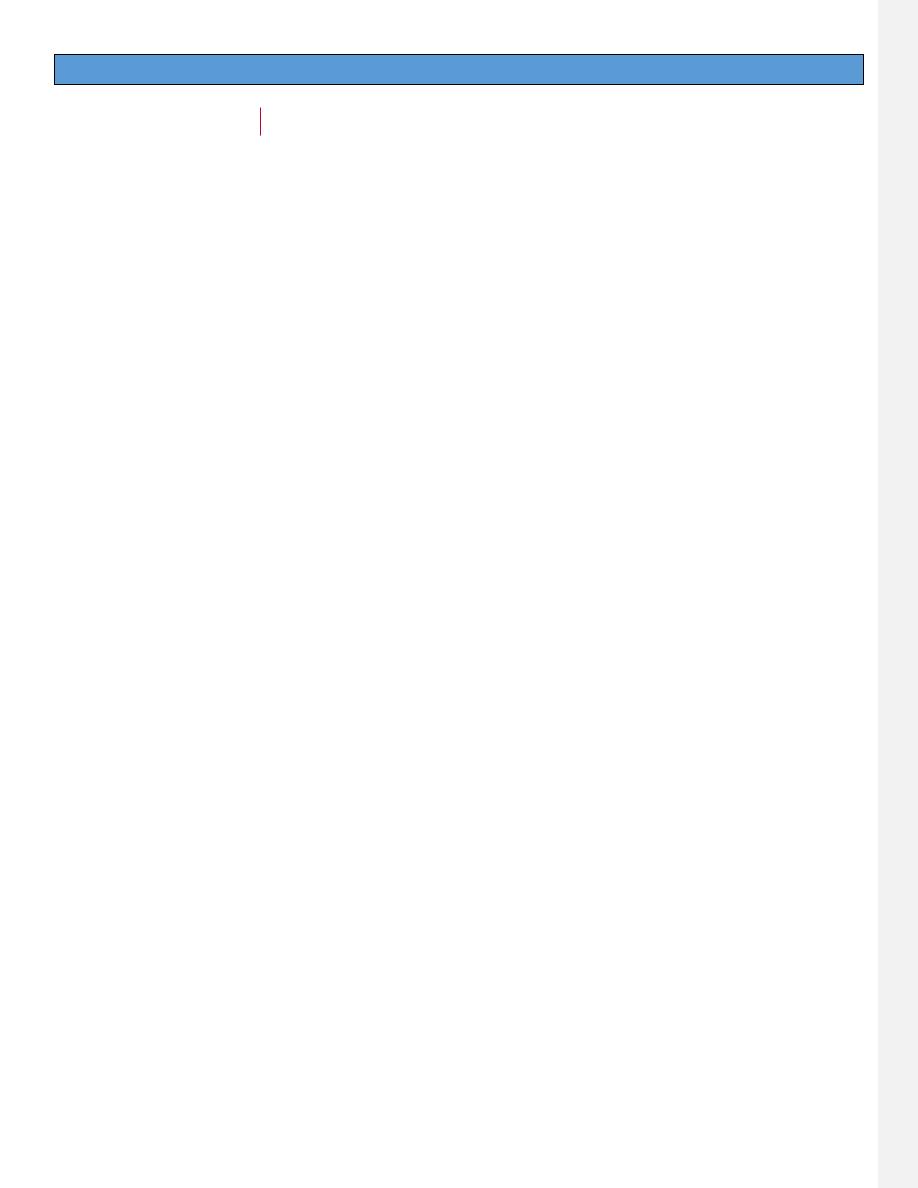

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY:

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli are inhaled through the lungs to

the alveoli. They are phagocytosed by polymorphonuclear leukocytes

and macrophages. Although most bacilli are initially contained, some are

carried to the region's lymph nodes. Eventually, the thoracic duct may

deliver mycobacteria to the venous blood; seeding of different organs,

including the kidneys, may occur.

- Multiple granuloma form at the site of metastatic foci.

- In the kidneys, they are typically bilateral, cortical, and adjacent to the

glomeruli. They may remain inactive for decades.

P a g e | 2 GU-TB G:E

Although both kidneys are seeded, clinically significant disease usually

occurs in only one kidney.

- Growing granuloma may erode into the calyceal system, spreading the

bacilli to the renal pelvis, ureters, bladder, and other genitourinary

organs.

- Depending on the status of the patient's defense mechanisms, fibrosis

and strictures may develop with chronic abscess formation.

- Extensive

lesions

can

result

in

nonfunctioning

kidneys

(Autonephrectomy).

Ureteral TB is an extension of the disease from the kidneys, generally to the

ureterovesical junction. causing ureteral strictures and hydronephrosis.

- The ureter undergoes fibrosis and tends to be shortened and therefore

straightened. This change leads to a “golf hole” (gaping) ureteral orifice

-

Ureteral stenosis may be complete, causing “autonephrectomy.” Such a

kidney is fibrosed and functionless. Under these circumstances, the

bladder urine may be normal and symptoms absent.

Bladder TB is secondary to renal TB and usually starts at the ureteral orifice.

It initially manifests as superficial inflammation with bullous edema and

granulation.

Fibrosis of the ureteral orifice can lead to stricture formation with

hydronephrosis or scarification (ie, golf-hole appearance) with

vesicoureteral reflux.

Severe cases involve the entire bladder wall, where deep layers of muscle

are eventually replaced by fibrous tissue, thus producing a thick, fibrous

bladder.

Epididymis TB is always hematogenous in origin and not a direct extension

from the bladder.

- If the epididymal infection is extensive and an abscess forms, it may

rupture through the scrotal skin, thus establishing a permanent sinus

- The nodular beading of the vas, when it is involved, is a characteristic

P a g e | 3 GU-TB G:E

physical finding. Infertility may result from bilateral vasal obstruction.

- Involvement of the testis is usually due to direct extension from the

epididymis.

Prostate TB is also spread hematogenously, but involvement is rare. The

affected prostate is nodular, indurated and not tender to palpation (? Ca

Prost.), Severe cases may cavitate and form a perineal sinus

P a g e | 4 GU-TB G:E

Clinical Findings

Tuberculosis of the genitourinary tract should be considered in the presence

of any of the following situations:

1. chronic cystitis that refuses to respond to adequate therapy,

2. the finding of sterile pyuria,

3. gross or microscopic hematuria,

4. a non-tender, enlarged epididymis with a beaded or thickened vas,

5. a chronic draining scrotal sinus,

6. induration or nodulation of the prostate and thickening of one or both

seminal vesicles (especially in a young man).

- A history of present or past tuberculosis elsewhere in the body should

cause the physician to suspect tuberculosis in the genitourinary tract

when signs or symptoms are present.

- There is no classic clinical picture of renal tuberculosis.

- Most symptoms of this disease, even in the most advanced stage, are

vesical in origin (cystitis).

- Vague generalized malaise, fatigability, low-grade but persistent fever,

and night sweats are some of the nonspecific complaints.

- Active tuberculosis elsewhere in the body is found in less than half of

patients with genitourinary tuberculosis.

Investigation:

The diagnosis rests on the demonstration of tubercle bacilli in the urine by

culture or positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

- Tuberculin skin test

- Complete blood cell count, sedimentation rate, serum chemistry, and C-

reactive protein studies are helpful to assess severity of disease, renal

function, and response to treatment.

- Serial early morning urine collection for acid-fast smear (at least 3)

- Serial urine cultures (Three to five first morning voided specimens are

ideal.) are still considered the criterion standard for evidence of active

disease,

P a g e | 5 GU-TB G:E

The following methods are available:

- Solid media: The Lowenstein-Jensen medium takes more than 4 weeks

for results.

- Radiometric media: The BACTEC 460 medium takes 2-3 days for results.

- The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test

Imaging Studies:

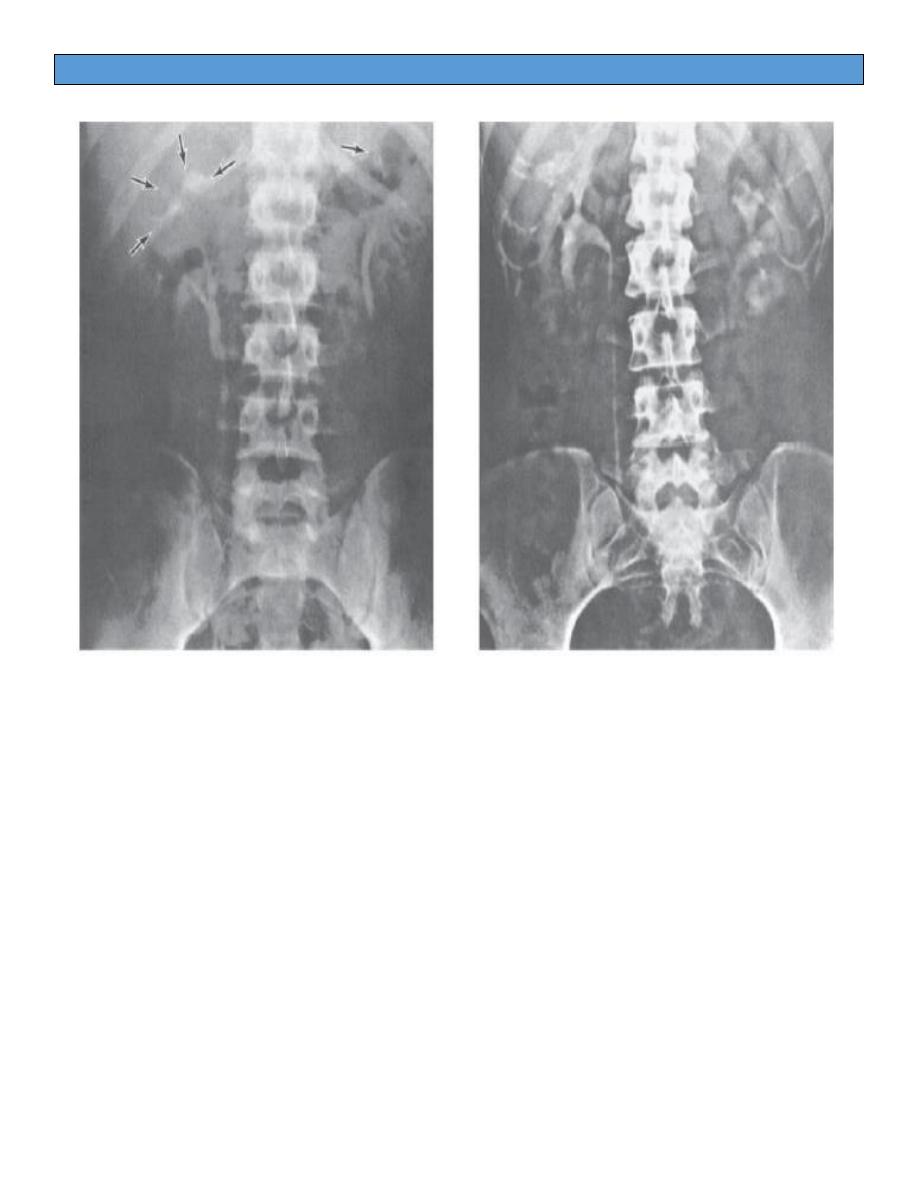

- Chest and spine radiographs may show old or active lesions

- (KUB) reveal calcifications in the kidney and ureter in approximately 50%

of patients.

- IVP and voiding cystography: are the standard diagnostic imaging

studies for renal TB and are suggestive of disease in 88-95% of patients.

The typical IVP changes include:

1.

a “moth-eaten” appearance of the involved ulcerate calyces,

2. obliteration of one or more calyces,

3. dilatation of the calyces due to ureteral stenosis from fibrosis,

4. abscess cavities that connect with calyces,

5. single or multiple ureteral strictures, with secondary dilatation, with

shortening and therefore straightening of the ureter,

6. absence of function of the kidney due to complete ureteral occlusion

and renal destruction (autonephrectomy).

P a g e | 6 GU-TB G:E

Medical Care: The primary treatment is medical therapy.

Standard treatment is: rifampin (600mg orally once daily), INH (300mg oral

once daily), pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2 months,

Then: rifampin and INH for 4 more months

Surgical Care: