Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

1

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Urinary Stones

Kidney stones: epidemiology

~10% of Caucasian men will develop a kidney stone by the age of 70.

Within 1 year of a calcium oxalate stone, 10% of men will form another calcium

oxalate stone, and 50% will have formed another stone within 10 years. The

prevalence of renal tract stone disease is determined by factors intrinsic to

the individual and by extrinsic (environmental) factors. A combination of

factors often contributes to risk of stone formation.

Intrinsic factors

Age. The peak incidence of stones occurs between the ages of 20-50

years.

Sex. Males are affected 3 times as frequently as females.

Genetic. ~25% of patients with kidney stones report a family history of

stone disease.

Extrinsic (environmental) factors

Geographical location, climate, and season.

Ureteric stones become more prevalent during the summer, the highest

incidence occurring a month or so after peak summertime temperatures,

presumably because of higher urinary concentration in the summer

(encourages crystallization). Concentrated urine has a lower pH,

encouraging cystine and uric acid stone formation. Exposure to sunlight

may also increase endogenous vitamin D production, leading to

hypercalciuria.

Water intake. Low fluid intake (<1200ml/day) predisposes to stone

formation.

Diet. High animal protein intake increases risk of stone disease (high

urinary oxalate, low pH, low urinary citrate). High salt intake causes

hypercalciuria. Contrary to conventional teaching, low calcium diets

predispose to calcium stone disease, and high calcium intake is protective.

Occupation. Sedentary occupations predispose to stones compared with

manual workers.

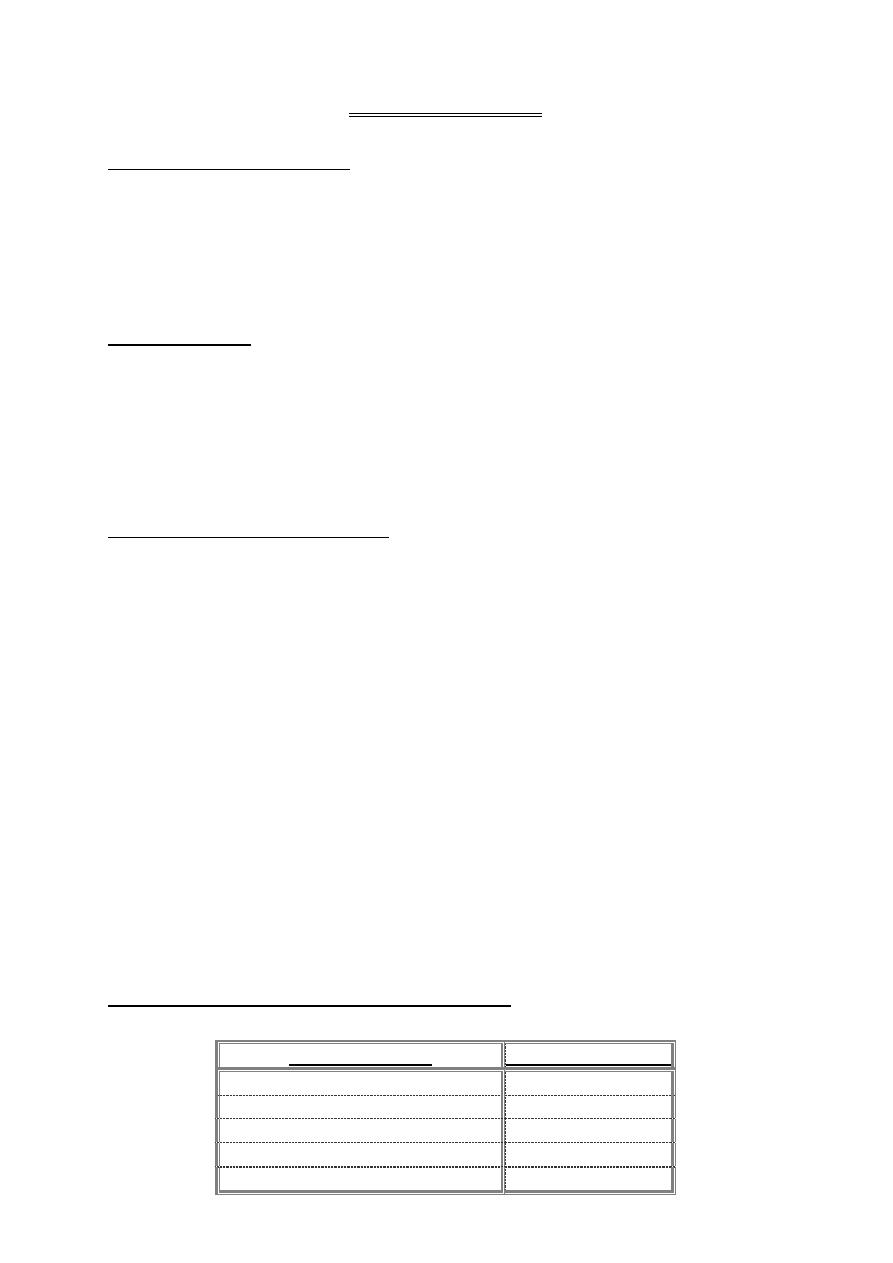

Kidney stones: types and predisposing factors

Stones may be classified according to composition, X-ray appearance, or size

and shape.

Stone composition

% of all renal calculi

Calcium oxalate

85%

Uric acid

5-10%

Calcium phosphate + calcium oxalate

10%

Struvite (infection stones)

2-20%

Cystine

1%

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

2

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Other rare stone types (all of which are radiolucent): indinavir

(a protease inhibitor used for treatment of HIV); triamterene (a relatively

insoluble potassium sparing diuretic, most of which is excreted in urine);

xanthine.

Radiodensity on X-ray

Radio-opaque

Opacity implies the presence of substantial amounts of calcium within the

stone. Calcium phosphate stones are the most radiodense stones, being almost

as dense as bone. Calcium oxalate stones are slightly less radiodense.

Relatively radiodense

Cystine stones are relatively radiodense because they contain sulphur.

Magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite) stones are less radiodense than

calcium containing stones.

Completely radiolucent

Uric acid, triamterene, xanthine, (indinavir cannot be seen even on CTU).

Size and shape

Stones can be characterized by their size, in centimeters. Stones which

grow to occupy the renal collecting system (the pelvis and one or more renal

calyx) are known as staghorn calculi, since they resemble the horns of a stag.

They are most commonly composed of struvite (magnesium ammonium

phosphate)(being caused by infection and forming under the alkaline conditions

induced by urea-splitting bacteria), but may be composed of uric acid, cystine,

or calcium oxalate monohydrate.

Kidney stones: mechanisms of formation

Periods of intermittent supersaturation of urine with various substances

can occur as a consequence of dehydration and following meals. The earliest

phase of crystal formation is known as nucleation. Crystal nuclei usually form on

the surfaces of epithelial cells or on other crystals. Crystal nuclei form into

clumps: a process known as aggregation. Citrate and magnesium not only inhibit

crystallization but also inhibit aggregation.

Factors predisposing to specific stone types

Calcium oxalate (~85% of stones)

Hypercalciuria

Hypercalcaemia: Almost all patients with hypercalcaemia who form stones

have primary hyperparathyroidism.

Hyperoxaluria

Hypocitraturia: Low urinary citrate excretion. Citrate forms a soluble

complex with calcium, so preventing complexing of calcium with oxalate to

form calcium oxalate stones.

Hyperuricosuria: High urinary uric acid levels

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

3

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Uric acid (~5-10% of stones)

Gout: 50% of patients with uric acid stones have gout.

Myeloproliferative disorders. Particularly following treatment with

cytotoxic drugs.

Idiopathic uric acid stones (no associated condition).

Calcium phosphate (calcium phosphate + calcium oxalate = 10% of stones)

Occur in patients with distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA)

Struvite (infection or triple phosphate stones) (2-20% of stones)

These stones are composed of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate.

They form as a consequence of urease-producing bacteria which produce

ammonia from breakdown of urea. Under alkaline conditions, crystals of

magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate precipitate.

Cystine (1% of all stones)

Occur only in patients with cystinuria: an inherited (autosomal-recessive)

disorder

Evaluation of the stone former

Determination of stone type and a metabolic evaluation allows

identification of the factors that led to stone formation, so advice can be given

to prevent future stone formation. Stone type is analyzed by polarizing

microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and infrared spectroscopy, rather than by

chemical analysis. Where no stone is retrieved, its nature must be inferred

from its radiological appearance (e.g. a completely radiolucent stone is likely to

be composed of uric acid) or from more detailed metabolic evaluation.

Risk factors for stone disease

Diet. Enquire about volume of fluid intake, meat consumption (causes

hypercalciuria, high uric acid levels, low urine pH, low urinary citrate),

multivitamins (vitamin D increases intestinal calcium absorption), high

doses of vitamin C (ascorbic acid causes hyperoxaluria).

Drugs. Corticosteroids (increase enteric absorption of calcium, leading to

hypercalciuria); chemotherapeutic agents (breakdown products of

malignant cells leads to hyperuricaemia).

Urinary tract infection. Urease-producing bacteria (Proteus, Klebsiella,

Serratia, Enterobacter) predispose to struvite stones.

Mobility. Low activity levels predispose to bone demineralization and

hypercalciuria.

Systemic disease. Gout, primary hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis.

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

4

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Family history. Cystinuria, RTA.

Renal anatomy. PUJO, horseshoe kidney.

Previous bowel resection or inflammatory bowel disease. Causes intestinal

hyperoxaluria.

Urine pH

Urine pH in normal individuals shows variation, from pH 5-7. After a meal,

pH is initially acid. This is followed by an alkaline tide, pH rising to >6.5. Urine

pH can help establish what type of stone the patient may have (if a stone is not

available for analysis), and can help the urologist and patient in determining

whether preventative measures are likely to be effective or not.

pH <6 in a patient with radiolucent stones suggests the presence of uric

acid stones.

pH consistently >5.5 suggests type 1 (distal) RTA (~70% of such patients

will form calcium phosphate stones).

Kidney stones: presentation and diagnosis

Kidney stones may present with symptoms or be found incidentally during

investigation of other problems. Presenting symptoms include pain or haematuria

(microscopic or occasionally macroscopic). Struvite staghorn calculi classically

present with recurrent UTIs. Malaise, weakness, and loss of appetite can also

occur. Less commonly, struvite stones present with infective complications

(pyonephrosis, perinephric abscess, septicaemia, xanthogranulomatous

pyelonephritis).

Diagnostic tests

Plain abdominal radiography: calculi that contain calcium are radiodense.

Sulphur-containing stones (cystine) are relatively radiodense on plain

radiography.

Radiodensity of stones in decreasing order: calcium phosphate > calcium

oxalate > struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) >> cystine.

Completely radiolucent stones (e.g. uric acid, triamterene, indinavir) are

usually suspected on the basis of the patient's history and/or urine pH ,

and the diagnosis may be confirmed by ultrasound, or CTU.

Renal ultrasound: its sensitivity for detecting renal calculi is ~95%.

A combination of plain abdominal radiography and renal ultrasonography is

a useful screening test for renal calculi.

IVU: increasingly being replaced by CTU. Useful for patients with

suspected indinavir stones (which are not visible on CT).

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

5

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

CTU: a very accurate method of diagnosing all but indinavir stones. Allows

accurate determination of stone size and location and good definition of

pelvicalyceal anatomy.

Kidney stone treatment options: watchful waiting

The traditional indications for intervention are pain, infection, and

obstruction. Haematuria caused by a stone is only very rarely severe or

frequent enough to be the only reason to warrant treatment.

Options for stone treatment are watchful waiting, ESWL, flexible

ureteroscopy, PCNL, open surgery, and medical dissolution therapy.

When to watch and wait and when not to?

It is not necessary to treat every kidney stone. Thus, one would be

inclined to do nothing about a 1cm symptomless stone in the kidney of

a 95-year-old patient. On the other hand, a 1cm stone in a symptomless

20-year-old runs the risk over the remaining (many) years of the patient's life

of causing problems. It could drop into the ureter causing ureteric colic, or it

could increase in size and affect kidney function or cause pain.

Asymptomatic stones which are followed over a 3-year period are more

likely to require intervention (surgery or ESWL) or to increase in size or cause

pain if they are >4mm in diameter and if they are located in a middle or lower

pole calyx.

Another factor determining the need for treatment is the patient's job.

Airline pilots are not allowed to fly if they have kidney stones, for fear that the

stones could drop into the ureter at 30,000ft, with disastrous consequences!

Some stones are definitely not suitable for watchful waiting. Untreated

struvite (i.e. infection related) staghorn calculi will eventually destroy the

kidney if untreated and are a significant risk to the patient's life. Watchful

waiting is therefore NOT recommended for staghorn calculi unless patient

comorbidity is such that surgery would be a higher risk than watchful waiting.

Historical series suggest that ~30% of patients with staghorn calculi who did

not undergo surgical removal died of renal related causes: renal failure,

urosepsis (septicaemia, pyonephrosis, perinephric abscess).

Stone fragmentation: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL)

The technique of focusing externally generated shock waves at a target

(the stone). First used in humans in 1980. The first commercial lithotriptor, the

Dornier HM3, became available in 1983. ESWL revolutionized kidney and

ureteric stone treatment. X-ray, ultrasound, or a combination of both are used

to locate the stone on which the shock waves are focused. Newer lithotriptors

generate less powerful shock waves, allowing ESWL with oral or parenteral

analgesia in many cases, but they are less efficient at stone fragmentation.

Efficacy of ESWL

Likelihood of fragmention with ESWL depends on stone size and location,

anatomy of renal collecting system, degree of obesity, and stone composition.

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

6

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Most effective for stones <2cm in diameter, in favourable anatomical locations.

Less effective for stones >2cm diameter, in lower pole stones in a calyceal

diverticulum (poor drainage), and those composed of cystine or calcium oxalate

monohydrate (very hard).

Side-effects of ESWL

ESWL causes a certain amount of structural and functional renal damage

(found more frequently the harder you look). Haematuria (microscopic,

macroscopic) and oedema are common, perirenal haematomas less so

(0.5% detected on ultrasound with modern machines, Effective renal plasma

flow (measured by renography) has been reported to fall in ~30% of treated

kidneys. There is data suggesting that ESWL may increase the likelihood of

development of hypertension. Acute renal injury may be more likely to occur in

patients with pre-existing hypertension, prolonged coagulation time, coexisting

coronary heart disease, diabetes, and in those with solitary kidneys.

Contraindications to ESWL

Absolute contraindications: pregnancy, uncorrected blood clotting disorders

(including anticoagulation).

Intracorporeal techniques of stone fragmentation (fragmentation within the

body)

Electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL)

Pneumatic (ballistic) lithotripsy

Ultrasonic lithotripsy

Laser lithotripsy: The holmium: YAG laser.

Kidney stone treatment: flexible ureteroscopy and laser treatment

It can also allow access to areas of the kidney where ESWL is less

efficient or where PCNL cannot reach. It is most suited to stones <2cm in

diameter. Indications for flexible ureteroscopic kidney stone treatment

ESWL failure.

Lower pole stone

Cystine stones.

Obesity such that PCNL access is technically difficult or impossible

(nephroscopes may not be long enough to reach stone).

Obesity such that ESWL is technically difficult or impossible.

Musculoskeletal deformities such that stone access by PCNL or ESWL is

difficult or impossible (e.g. kyphoscoliosis).

Stone in a calyceal diverticulum.

Bleeding diathesis where reversal of this diathesis is potentially

dangerous or difficult.

Patient preference.

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

7

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Kidney stone treatment: percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

PCNL is the removal of a kidney stone via a track developed between the

surface of the skin and the collecting system of the kidney. A posterior

approach is most commonly used; below the 12th rib (to avoid the pleura and far

enough away from the rib to avoid the intercostals, vessels, and nerve). The

preferred approach is through a posterior calyx, rather than into the renal

pelvis, because this avoids damage to posterior branches of the renal artery

which are closely associated with the renal pelvis. General anaesthesia is usual,

though regional or even local anaesthesia (with sedation) can be used.

Indications for PCNL

PCNL is generally recommended for stones >3cm in diameter, those that

have failed ESWL and/or an attempt at flexible ureteroscopy and laser

treatment. It is the first-line option for staghorn calculi, with ESWL and/or

repeat PCNL being used for residual stone fragments.

For stones 2-3cm in diameter, options include ESWL (with a JJ stent in

situ), flexible ureteroscopy and laser treatment, and PCNL.

Kidney stones: open stone surgery

Indications

Complex stone burden (projection of stone into multiple calyces, such

that multiple PCNL tracks would be required to gain access to all the

stone)

Failure of endoscopic treatment

Anatomic abnormality that precludes endoscopic surgery (e.g. retrorenal

colon)

Body habitus that precludes endoscopic surgery (e.g. gross obesity,

kyphoscoliosis)

Patient request for a single procedure where multiple PCNLs might be

required for stone clearance

Non-functioning kidney

Non-functioning kidney

If the kidney is non-functioning, the simplest way of removing the stone

is to remove the kidney.

Functioning kidneys options for stone removal

Small- to medium-sized stones: Pyelolithotomy, Radial nephrolithotomy.

Staghorn calculi

Anatrophic (avascular) nephrolithotomy

Extended pyelolithotomy with radial nephrotomies (small incisions over

individual stones)

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

8

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Specific complications of open stone surgery

Wound infection (the stones operated on are often infection stones);

flank hernia; wound pain. (With PCNL these problems do not occur, blood

transfusion rate is lower, analgesic requirement is less, mobilization is more

rapid and discharge earlier; all of which account for PCNL having replaced open

surgery as the mainstay of treatment of large stones.) There is a significant

chance of stone recurrence after open stone surgery (as for any other

treatment modality) and the scar tissue that develops around the kidney will

make subsequent open stone surgery technically more difficult.

Kidney stones: medical therapy (dissolution therapy)

Uric acid and cystine stones are suitable for dissolution therapy. Calcium

within either stone type reduces the chances of successful dissolution.

Uric acid stones

Uric acid stones form in concentrated, acid urine. Dissolution therapy is

based on hydration, urine alkalinization, allopurinol, and dietary manipulation:

the aim being to reduce urinary uric acid saturation. Maintain a high fluid intake

(urine output 2-3L/day), alkalinize the urine to pH 6.5-7. In those with

hyperuricaemia, add allopurinol 300mg/day. Dissolution of large stones

(even staghorn calculi) is possible with this regimen.

Cystine stones

Reduce cystine excretion (dietary restriction of the cystine precursor

amino acid methionine and also of sodium intake to <100mg/day).

Increase solubility of cystine by alkalinization of the urine to >pH 7.5,

maintenance of a high fluid intake, and use of drugs which convert cystine

to more soluble compounds.

Ureteric stones: presentation

Ureteric stones usually present with sudden onset of severe flank pain

which is colicky (waves of increasing severity are followed by a reduction in

severity, but it seldom goes away completely). It may radiate to the groin as the

stone passes into the lower ureter. Examination

Spend a few seconds looking at the patient. Ureteric stone pain is colicky

the patient moves around, trying to find a comfortable position. Patients with

conditions causing peritonitis (e.g. appendicitis, a ruptured ectopic pregnancy)

lie very still: movement and abdominal palpation are very painful. Many patients

with ureteric stones have dipstick or microscopic haematuria (and, more rarely,

macroscopic haematuria. The most important aspect of examination in a patient

with a ureteric stone confirmed on imaging is to measure their temperature. If

the patient has a stone and a fever, they may have infection proximal to the

stone. A fever in the presence of an obstructing stone is an indication for urine

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

9

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

and blood culture, intravenous fluids and antibiotics, and nephrostomy drainage

if the fever does not resolve within a matter of hours.

Ureteric stones: diagnostic radiological imaging

The intravenous urogram (IVU), for many years the mainstay of imaging in

patients with flank pain, has been replaced by CT urography (CTU). Compared

with IVU, CTU:

Has greater specificity (95%) and sensitivity (97%) for diagnosing

ureteric stones: it can identify other, non-stone causes of flank pain .

Requires no contrast administration so avoiding the chance of a contrast

reaction (risk of fatal anaphylaxis following the administration of low-

osmolality contrast media for IVU is in the order of 1 in 100,000).

Is faster, taking just a few minutes to image the kidneys and ureters. An

IVU, particularly where delayed films are required to identify a stone

causing high-grade obstruction, may take hours to identify the precise

location of the obstructing stone.

Is equivalent in cost to IVU, in hospitals where high volumes of CT scans

are done.

If you only have access to IVU, remember that it is contraindicated in

patients with a history of previous contrast reactions and should be avoided in

those with hay fever, a strong history of allergies, or asthma who have not been

pre-treated with high-dose steroids 24h before the IVU. Patients taking

metformin for diabetes should stop this for 48h prior to an IVU. Clearly, being

able to perform an alternative test, such as CTU in such patients, is very useful.

Plain abdominal X-ray and renal ultrasound are not sufficiently sensitive or

specific for their routine use for diagnosing ureteric stones.

Ureteric stones: acute management

While appropriate imaging studies are being organized, pain relief should be

given.

A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (e.g. diclofenac) by intramuscular or

intravenous injection, by mouth or per rectum. Provides rapid and

effective pain control. Analgesic effect: partly anti-inflammatory, partly

by reducing ureteric peristalsis.

Where NSAIDS are inadequate, opiate analgesics such as pethidine or

morphine are added

There is no need to encourage the patient to drink copious amounts of

fluids nor to give them large volumes of fluids intravenously in the hope that

this will flush the stone out. Renal blood flow and urine output from the

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

11

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

affected kidney falls during an episode of acute, partial obstruction due to a

stone. Excess urine output will tend to cause a greater degree of

hydronephrosis in the affected kidney which will make ureteric peristalsis even

less efficient .

Watchful waiting

In many instances, small ureteric stones will pass spontaneously within

days or a few weeks, with analgesic supplements for exacerbations of pain.

Chances of spontaneous stone passage depend principally on stone size. Between

90-98% of stones measuring <4mm will pass spontaneously. Average time for

spontaneous stone passage for stones 4-6mm in diameter is 3 weeks. Stones

that have not passed in 2 months are unlikely to do so.

Ureteric stones: indications for intervention to relieve obstruction and/or

remove the stone

Pain which fails to respond to analgesics or recurs and cannot be

controlled with additional pain relief.

Fever. Have a low threshold for draining the kidney (usually done by

percutaneous nephrostomy).

Impaired renal function (solitary kidney obstructed by a stone, bilateral

ureteric stones, or pre-existing renal impairment which gets worse as a

consequence of a ureteric stone). Threshold for intervention is lower.

Prolonged unrelieved obstruction. This can result in long-term loss of

renal function. How long it takes for this loss of renal function to occur is

uncertain, but generally speaking the period of watchful waiting for

spontaneous stone passage tends to be limited to 4-6 weeks.

Social reasons. Young, active patients may be very keen to opt for

surgical treatment because they need to get back to work or their

childcare duties, whereas some patients will be happy to sit things out.

Airline pilots and some other professions are unable to work until they

are stone free.

Emergency temporizing and definitive treatment of the stone

Where the pain of a ureteric stone fails to respond to analgesics or

where renal function is impaired because of the stone, then temporary relief of

the obstruction can be obtained by insertion of a JJ stent or percutaneous

nephrostomy tube. Stone may pass down and out of the ureter with a stent or

nephrostomy in situ, but in many instances it simply sits where it is and

subsequent definitive treatment is still required. While JJ stents can relieve

stone pain, they can cause bothersome irritative bladder symptoms (pain in the

bladder, frequency, and urgency). JJ stents do make subsequent stone

treatment in the form of ureteroscopy technically easier by causing passive

dilatation of the ureter.

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

11

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

The patient may elect to proceed to definitive stone treatment by

immediate ureteroscopy (for stones at any location in the ureter) or ESWL

(if the stone is in the upper and lower ureter: ESWL cannot be used for stones

in the mid ureter because this region is surrounded by bone, which prevents

penetration of the shock waves).

Ureteric stone treatment

Many ureteric stones are 4mm in diameter or smaller and most such

stones (90%) will pass spontaneously, given a few weeks of watchful waiting,

with analgesics for exacerbations of pain. Average time for spontaneous stone

passage for stones 4-6mm in diameter is 3 weeks. Stones that have not passed

in 2 months are much less likely to do so, though large stones do sometimes

drop out of the ureter at the last moment.

Treatment options for ureteric stones

ESWL: in situ; after push-back into the kidney (i.e. into the renal pelvis

or calyces); or after JJ stent insertion

Ureteroscopy

PCNL

Open ureterolithotomy

Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy

The stone clearance rates for ESWL are stone-size dependent. ESWL is

more efficient for stones <1cm in diameter compared with those >1cm in size.

Conversely, the outcome of ureteroscopy is somewhat less dependent on stone

size.

Recommendations

Proximal ureteric stones

<1cm diameter: ESWL (in situ, push-back)

>1cm diameter: ESWL, ureteroscopy, PCNL

Distal ureteric stones

Both ESWL and ureteroscopy are acceptable options.

Stone free rate <1cm: 80-90% for both ESWL and ureteroscopy; >1cm:

75% for both ESWL and ureteroscopy.

Failed initial ESWL is associated with a low success rate for subsequent

ESWL. Therefore, if ESWL has no effect after 1 or 2 treatments, change

tactics.

Open ureterolithotomy and laparoscopic ureterolithotomy are used where

ESWL or ureteroscopy have been tried and failed, or were not feasible.

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

12

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Bladder stones

Composition

Struvite (i.e. they are infection stones) or uric acid (in non-infected urine).

Adults

Bladder calculi are predominantly a disease of men aged >50 and with

bladder outlet obstruction due to BPH. They also occur in the chronically

catheterized patient (e.g. spinal cord injury patients

).

Children

Bladder stones are still common in Thailand, Indonesia, North Africa, and

the Middle East. In these endemic areas they are usually composed of

a combination of ammonium urate and calcium oxalate. A low-phosphate diet in

these areas (a diet of breast milk and polished rice or millet) results in high

peaks of ammonia excretion in the urine.

Symptoms

May be symptomless (incidental finding on KUB X-ray or bladder

ultrasound or on cystoscopy. In the neurologically intact patient: suprapubic or

perineal pain, haematuria, urgency and/or urge incontinence, recurrent UTI,

LUTS (hesitancy, poor flow).

Diagnosis

If you suspect a bladder stone, they will be visible on KUB X-ray or renal

ultrasound .

Treatment

Most stones are small enough to be removed cystoscopically (endoscopic

cystolitholapaxy), using stone-fragmenting forceps for stones that can be

engaged by the jaws of the forceps and EHL or pneumatic lithotripsy for those

that cannot. Large stones can be removed by open surgery (open

cystolithotomy).

Prevention of calcium oxalate stone formation

Low fluid intake

Low fluid intake may be the single most important risk factor for

recurrent stone formation. High fluid intake is protective, by reducing urinary

saturation of calcium, oxalate, and urate. Time to recurrent stone formation is

prolonged from 2 to 3 years in previous stone formers randomized to high fluid

vs. low fluid intake.

Dietary calcium

Conventional teaching was that high calcium intake increases the risk of

calcium oxalate stone disease. The Harvard Medical School studies have shown

that low calcium intake is, paradoxically, associated with an increased risk of

forming kidney stones, in both men and women

Tikrit Medical College, Urology, Fifth year

13

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Calcium supplements

It is possible that consuming calcium supplements with a meal or with

oxalate-containing foods could reduce this small risk of inducing kidney stones.

Animal proteins

High intake of animal proteins causes increased urinary excretion of

calcium, reduced pH, high urinary uric acid, and reduced urinary citrate, all of

which predispose to stone formation.

Vegetarian diet

Vegetable proteins contain less of the amino acids phenylalanin, tyrosine,

and tryptophan that increase the endogenous production of oxalate. A

vegetarian diet may protect against the risk of stone formation.

Dietary oxalate

A small increase in urinary oxalate concentration increases calcium

oxalate supersaturation much more than does an increase in urinary calcium

concentration. Mild hyperoxaluria is one of the main factors leading to calcium

stone formation.