1

Impacted Canine in Orthodontics

Tooth impaction can be defined as the infra-osseous position of the tooth after the

expected time of eruption, whereas the anomalous infra-osseous position of the canine

before the expected time of eruption can be defined as a displacement.

Theories regarding the causes of palatal displacement

1. Long path of eruption

2. Crowding

3. Non-resorption of the root of the deciduous canine

4. Trauma

5. Soft tissue pathology

6. Heredity

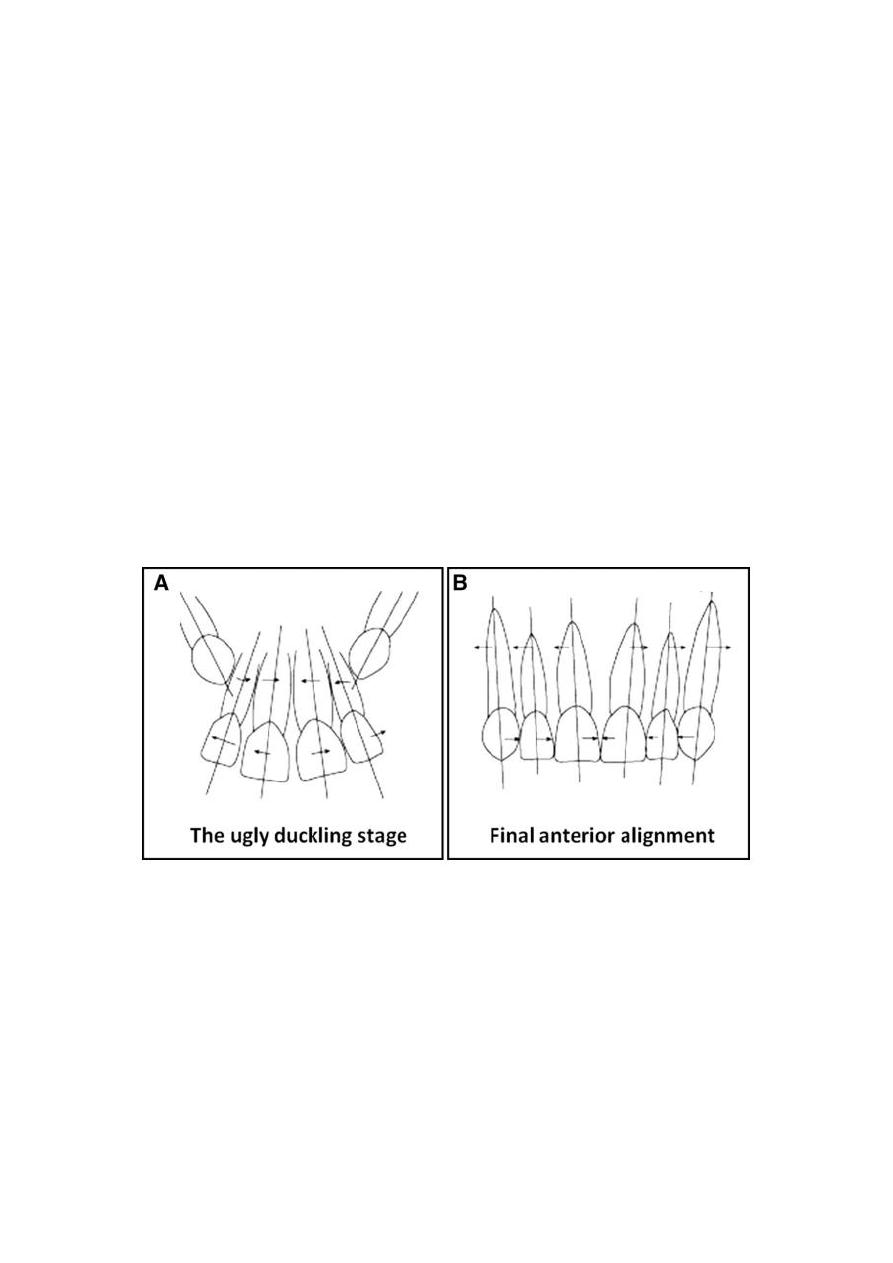

Diagrammatic representation of the relationships between the maxillary incisors, and between them and

the unerupted canines in normal development in a 9- to 10-year-old patient. The canines restricted the

roots into a narrowed apical area, causing lateral flaring of the incisor crowns. B, Diagrammatic

representation of the final alignment and long axis reorientation after eruption of the canines.

Causes of canine impaction

The causes can be classified into 4 distinct groupings: local hard tissue obstruction,

local pathology, departure from or disturbance of the normal development of the

incisors, and hereditary or genetic factors.

2

According to that aetiology for impacted canines could be due to:

1. Presence of supernumeraries

2. Odontomes

3. Pathological lesions, eg cysts

4. Delayed exfoliation of the deciduous canine (although this is thought to be an

indicator rather than a cause of displacement)

5. Early trauma to the maxilla

6. Cleft lip and palate

7. Ankylosis

8. Displacement of crypt

9. Long path of eruption

10. Syndromes, eg cleidocranial dysplasia.

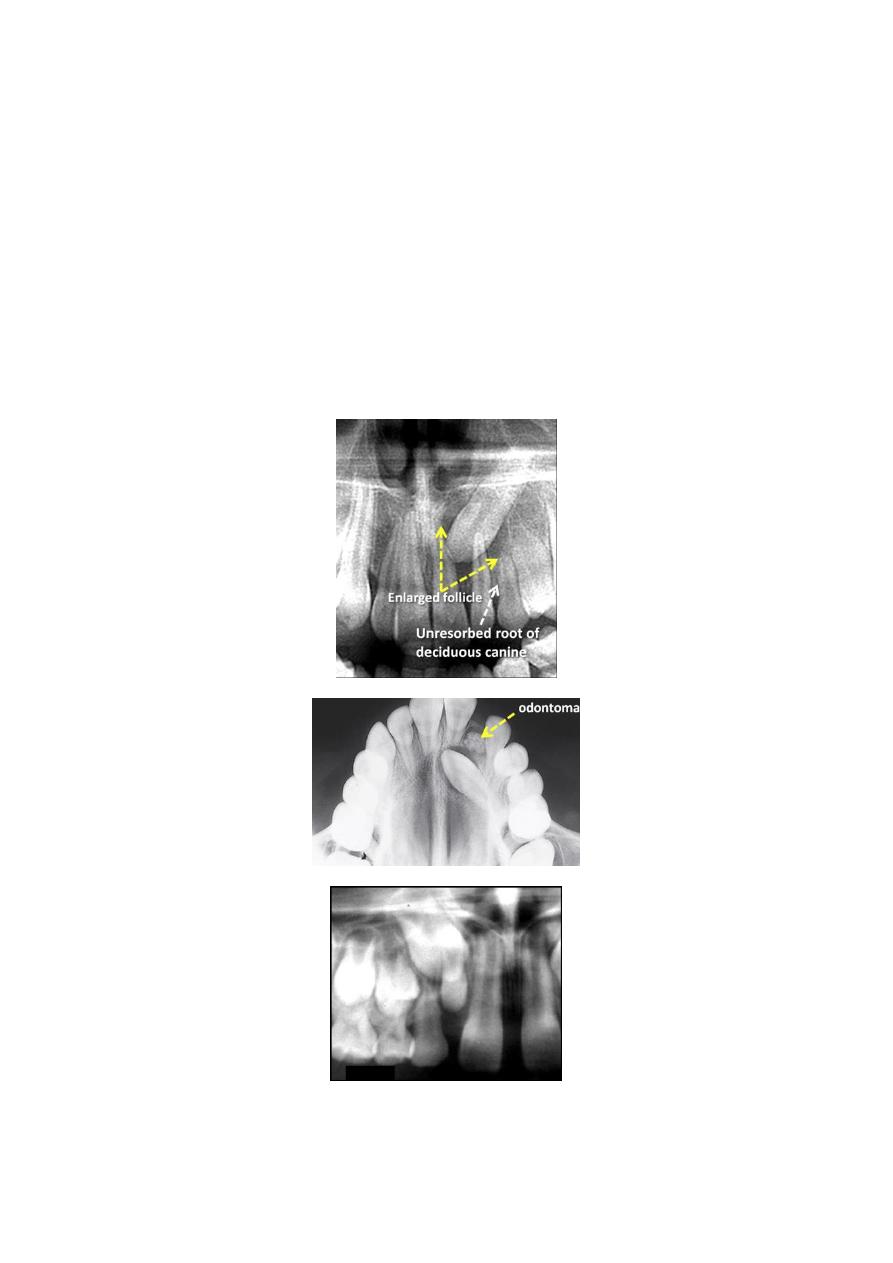

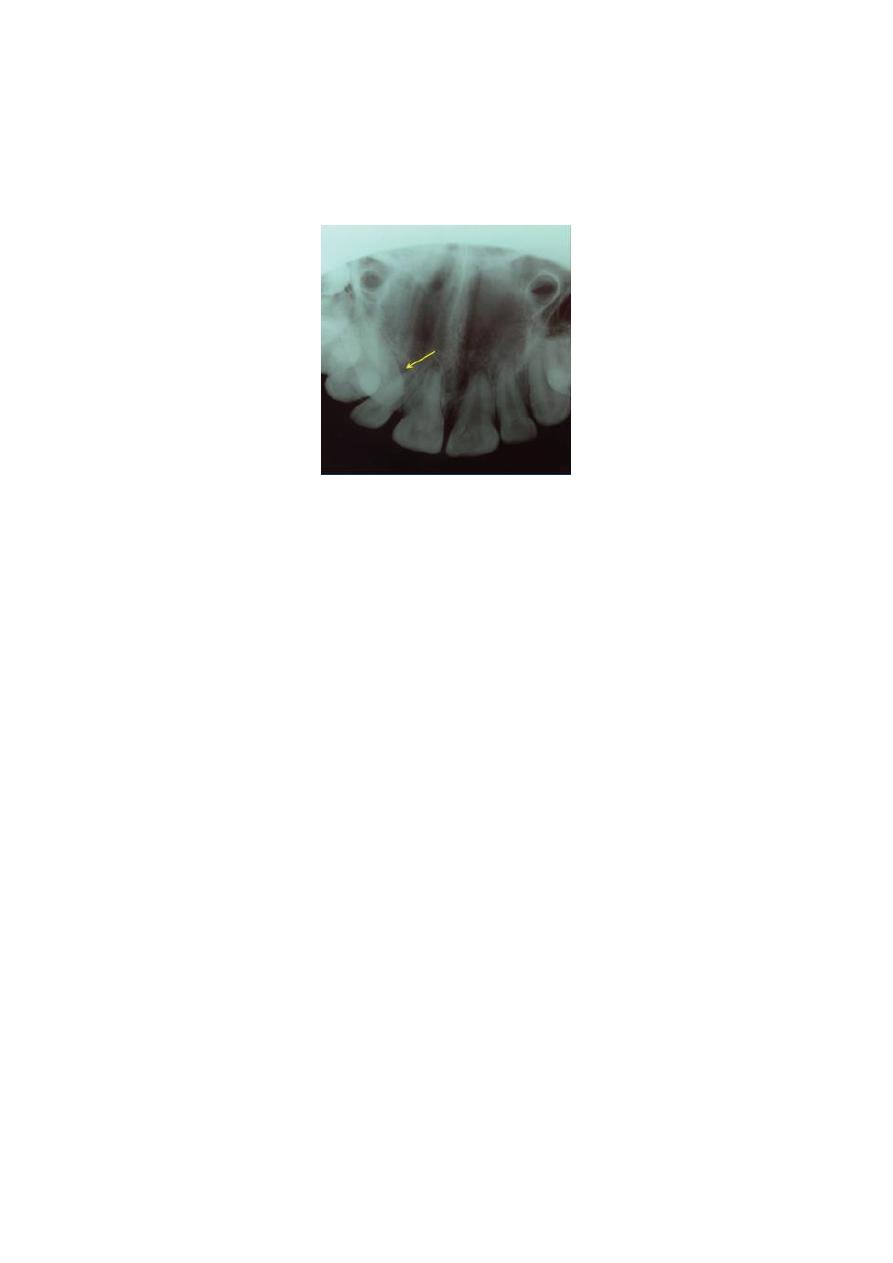

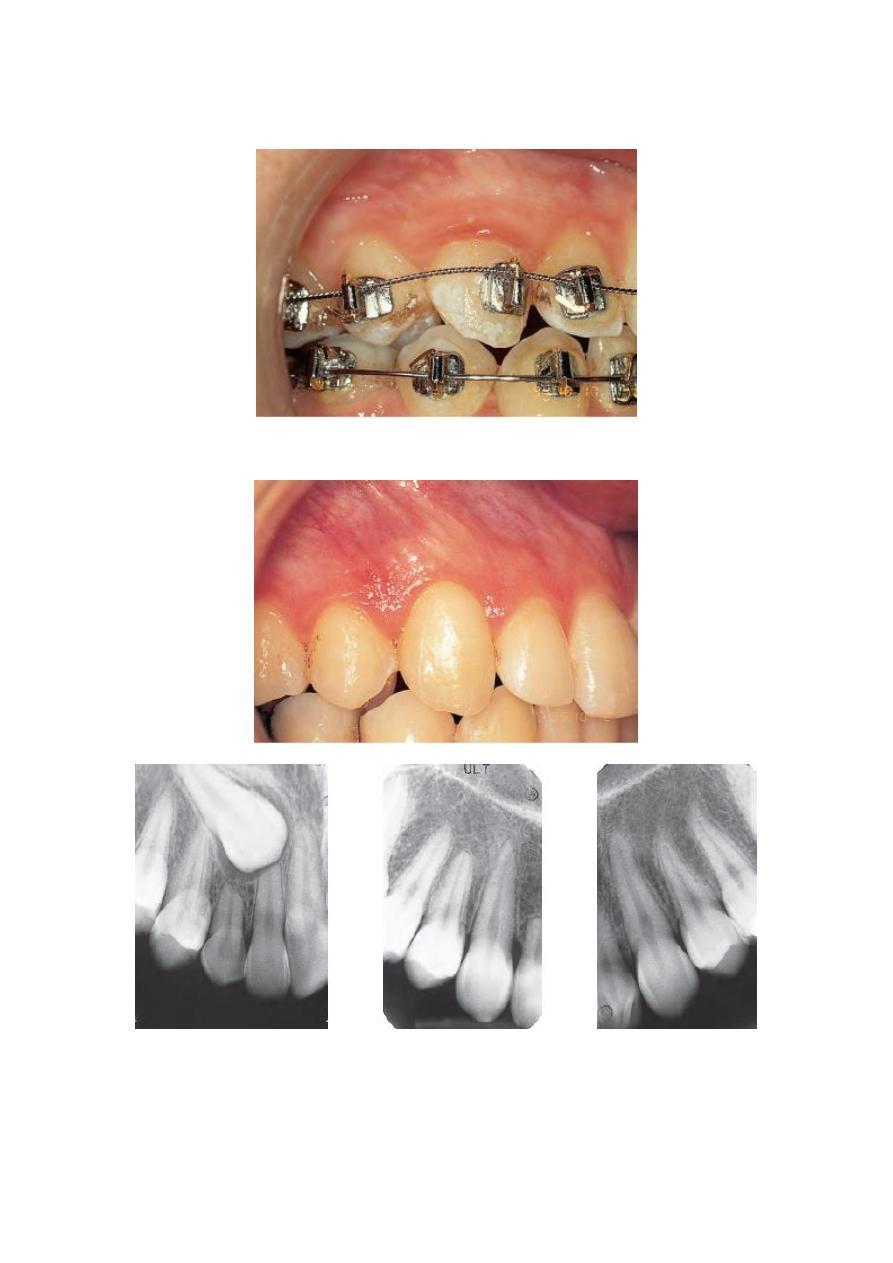

The crown of the unerupted lateral incisor is reduced in size and mildly peg shaped, whereas its

developing root has a length normally seen at age 4 to 5 years ( for image No.3).

3

Sequelae of Canine Impaction

1. Labial or lingual mal-positioning of the impacted tooth,

2. Migration of the neighboring teeth and loss of arch length,

3. Internal resorption,

4. Dentigerous cyst formation,

5. External root resorption of the impacted tooth, as well as the neighboring teeth,

6. Infection particularly with partial eruption, and

7. Referred pain and combinations of the above sequelae.

Diagnosis of Canine Impaction

The diagnosis of canine impaction is based on both clinical and radiographic

examinations.

Clinical assessment

Clinical investigation involves the following:

Visual inspection of the canine bulge, whether it is buccal or palatal which should be

seen between the lateral incisor and first premolar roots, and inspection of the

angulation of the lateral incisor, eg a distally inclined lateral incisor may infer palatal

impaction and a mesially inclined lateral incisor may indicate buccal impaction). In

addition, the colour and mobility of the deciduous canine should be inspected as this

might indicate resorption of the root.

4

Palpation of the buccal surface of the alveolar process distal to the lateral incisor from

8 years of age may reveal the position of the maxillary canine and has been

recommended as a diagnostic tool.

It has been suggested that the following clinical signs might be indicative of canine

impaction:

1. Delayed eruption of the permanent canine or prolonged retention of the deciduous

canine beyond 14–15 years of age,

2. Absence of a normal labial canine bulge,

3. Presence of a palatal bulge, and

4. Delayed eruption, distal tipping, or migration (splaying) of the lateral incisor.

Radiographic assessment

Although various radiographic exposures including occlusal films, panoramic views,

and lateral cephalograms can help in evaluating the position of the canines, in most

cases, periapical films are uniquely reliable for that purpose.

Periapical films

A single periapical film provides the clinician with a two-dimensional representation

of the dentition. In other words, it would relate the canine to the neighboring teeth

both mesio-distally and supero-inferiorly. To evaluate the position of the canine

bucco-lingually, a second periapical film should be obtained by one of the following

methods.

Tube-shift technique or Clark's rule or (SLOB) rule

Two periapical films are taken of the same area, with the horizontal angulation of the

cone changed when the second film is taken. If the object in question moves in the

same direction as the cone, it is lingually positioned. If the object moves in the

opposite direction, it is situated closer to the source of radiation and is therefore

buccally located.

Buccal-object rule

If the vertical angulation of the cone is changed by approximately 20° in two

successive periapical films, the buccal object will move in the direction opposite to

the source of radiation. On the other hand, the lingual object will move in the same

direction as the source of radiation. The basic principle of this technique deals with

the foreshortening and elongation of the images of the films.

5

Occlusal films

Also help to determine the bucco-lingual position of the impacted canine in

conjunction with the periapical films, provided that the image of the impacted canine

is not superimposed on the other teeth.

Extra-oral films

Frontal and lateral cephalograms

These can sometimes aid in the determination of the position of the impacted canine,

particularly its relationship to other facial structures (e.g., the maxillary sinus and the

floor of the nose).

Panoramic films

These are also used to localize impacted teeth in all three planes of space, as much the

same as with two periapical films in the tube-shift method, with the understanding

that the source of radiation comes from behind the patient; thus, the movements are

reversed for position.

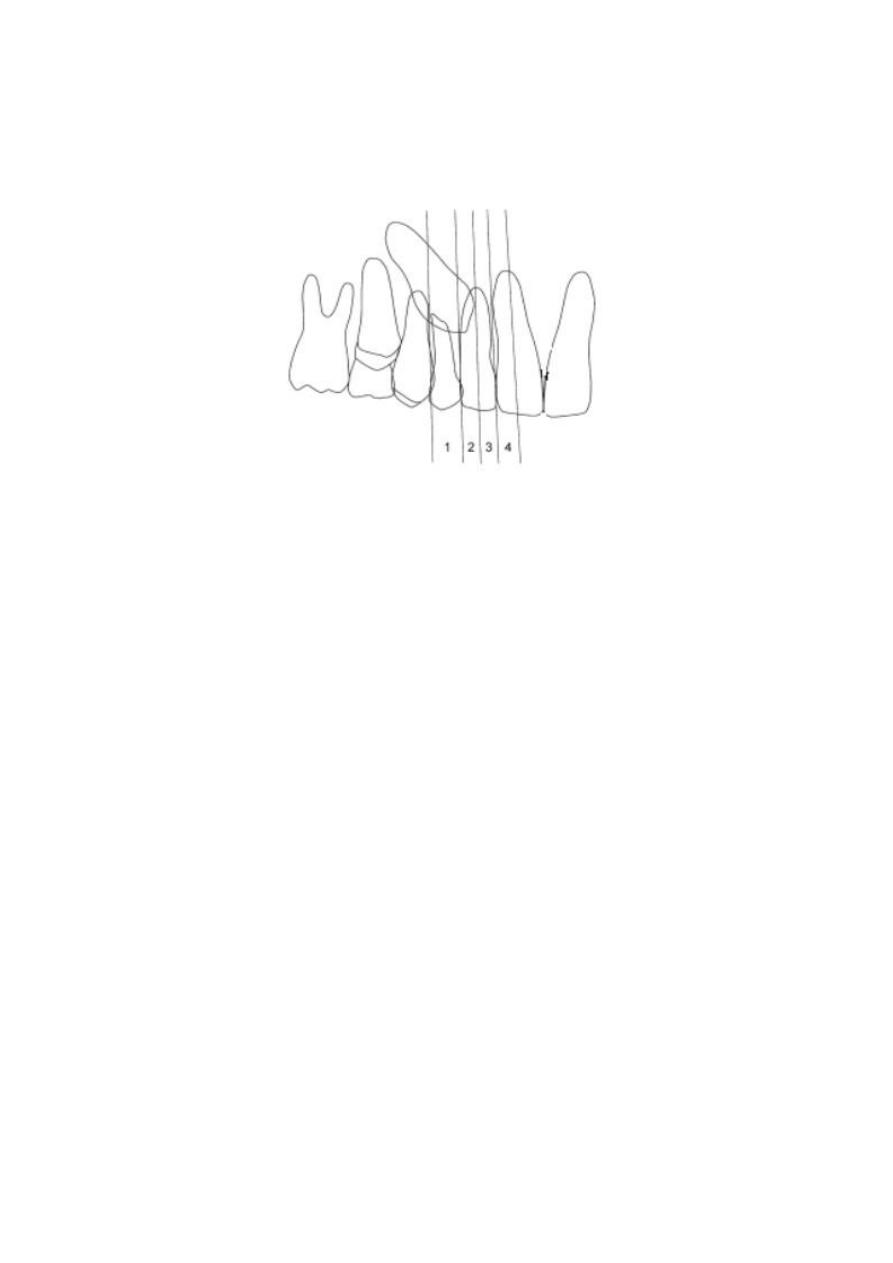

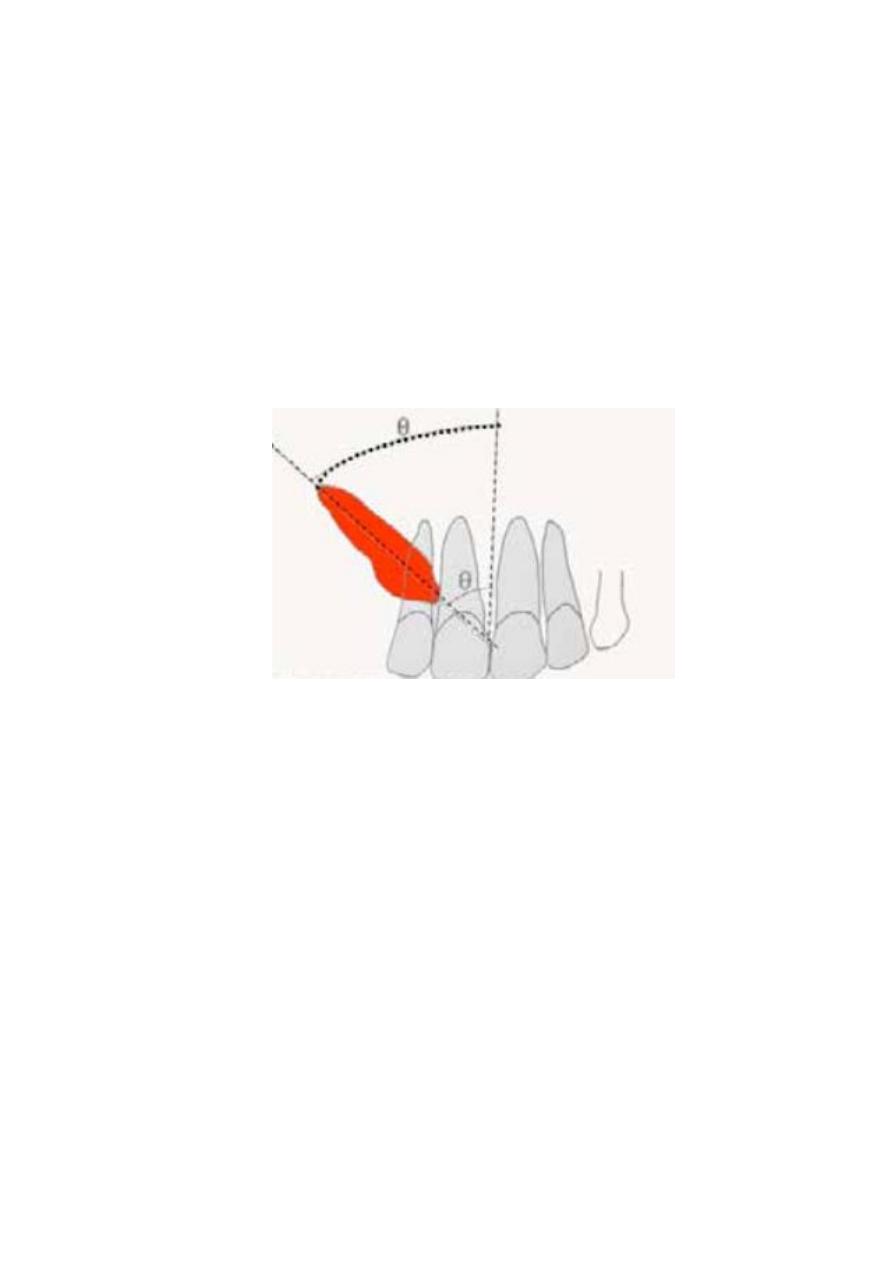

A method based on the location of the impacted canine

cusp tip and its relationship to

the adjacent lateral incisor was developed. Dividing impacted

canines into four

groups—sectors I through IV, with sector IV representing the

most severe

impaction—as many as 78% of the canines with

cusp tips in sectors II through IV

were destined to become impacted.

Sector I: cusp tip distal to a line tangent to the distal heights of

contour of the lateral

incisor crown and root.

Sector II: mesial to sector I, with the cusp tip distal to a line

bisecting the mesiodistal

dimension of the lateral incisor along the long

axis.

Sector III: mesial to sector II, with the cusp tip distal to a line tangent to

the mesial heights of contour of the lateral incisor crown and root.

6

Sector IV: any position mesial to sector III.

CT/CBCT

Clinicians can localize canines by using advanced three-dimensional imaging

techniques.

Because of superimposition of structure on the film it become difficult to

distinguish the details which makes the diagnosis and treatment planning difficult

with conventional radiographic methods. To be in a position to recommend best line

of treatment and to plan appropriate mechanotherapy strategy the orthodontist

requires following information:

1. The exact position of the crown and root apex of the impacted tooth and orientation

of the long axis.

2. The proximity of the impacted tooth to the roots of the adjacent teeth.

3. The presence of pathology, such as supernumerary teeth, apical granulomas, or

cysts, and their relationship with the impacted tooth.

4. The presence of adverse conditions affecting adjacent teeth, including root

resorption.

5. The anatomy and position of crown and root

Treatment

In normal circumstances, by the age of 9–10, it is usually possible to palpate a

normally developing maxillary permanent canine tooth on the buccal side of the

alveolus, high above its deciduous predecessor. In the presence of crowding, and

particularly after the eruption of the first premolar, the bulging of the unerupted

canine is emphasized. The greater the degree of crowding the greater will be this

displacement and the more palpable will the canine become, as its eruptive process

brings it further and further down on the facial side of the dental arch. It follows, too,

that the greater the buccal displacement the greater the risk that it will erupt through

oral mucosa, higher up the alveolar process, rather than through attached gingiva.

7

In the event that the tooth is not palpable at this age, radiographs should be taken to

assist in locating the tooth accurately and to secure other information regarding the

presence, size, shape, position and state of development of individual unerupted teeth

and any pathology. In a patient younger than 9 years, the radiographs will not usually

show abnormality in the position of the unerupted canine teeth, even if the canines are

not palpable and even if they are destined subsequently to become palatally displaced.

Many of these non-palpable canines will finally erupt into good positions in the dental

arch in their due time, provided that there is little or no mesial and palatal

displacement of the crown of the unerupted tooth. It may be argued that even canines

with an initial mild palatal displacement will achieve spontaneous eruption and

alignment despite a first-stage displacement. Other canines, however, will not erupt,

and their positions may worsen in time, as may be seen in follow-up radiographs. If it

were possible to distinguish between the two early enough, a line of preventive

treatment might be advised

Interceptive Treatment

When the clinician detects early signs of ectopic eruption of the canines, an attempt

should be made to prevent their impaction and its potential sequelae. Selective

extraction of the deciduous canines as early as 8 or 9 years of age has been suggested

as an interceptive approach to canine impaction in Class I

un crowded cases

.

removal of the deciduous canine before the age of 11 years will normalize the position

of the ectopically erupting permanent canines in 91% of the cases if the canine crown

is distal to the midline of the lateral incisor. On the other hand, the success rate is only

64% if the canine crown is mesial to the midline of the lateral incisor

Schematic illustration showing the normalization rates of the maxillary canine after extraction

of the primary canine when the permanent maxillary canine is located mesially and distally to

the midline of the lateral incisor.

8

The extraction of a maxillary deciduous canine may be a useful measure in the

prevention of incipient canine impaction. To achieve maximum reliability, the

following conditions should be met before extraction is advised:

1. The diagnosis of palatal displacement must be made as early as possible.

2. The patient must be in the 10–13-year age range, preferably with a delayed

dental age.

3. Accurate identification of the position of the apex should be made and

confirmed to be in the line of the arch.

4. Medial overlap of the unerupted canine cusp tip should be less than half-way

across the root of the lateral incisor, on the panoramic view.

5.

The angulation of the long axis should be less than 55° to the mid-sagittal

plane.

Treatment alternatives

Each patient with an impacted canine must undergo a comprehensive evaluation of

the malocclusion. The clinician should then consider the various treatment options

available for the patient, including the following:

1. No treatment if the patient does not desire it. In such a case, the clinician should

periodically evaluate the impacted tooth for any pathologic changes. It should be

remembered that the long-term prognosis for retaining the deciduous canine is poor,

regardless of its present root length and the esthetic acceptability of its crown. This is

because, in most cases, the root will eventually resorb and the deciduous canine will

have to be extracted.

2. Auto transplantation of the canine.

3. Extraction of the impacted canine and movement of a first premolar in its position.

4. Extraction of the canine and posterior segmental osteotomy to move the buccal

segment mesially to close the residual space.

9

5. Prosthetic replacement of the canine.

6. Surgical exposure of the canine and orthodontic treatment to bring the tooth into the

line of occlusion. This is obviously the most desirable approach.

When to Extract an Impacted Canine

It should be emphasized that extraction of the labially erupting and crowded canine,

unsightly as this tooth may look, is contraindicated. Such an extraction might

temporarily improve the esthetics, but may complicate and compromise the

orthodontic treatment results, including the ability to provide the patient with a

functional occlusion. The extraction of the canine, although seldom considered, might

be a workable option in the following situations:

1. If it is ankylosed and cannot be transplanted,

2. If it is undergoing external or internal root resorption,

3. If its root is severely dilacerated,

4. If the impaction is severe (e.g., the canine is lodged between the roots of the central

and lateral incisors and orthodontic movement will jeopardize these teeth),

5. If the occlusion is acceptable, with the first premolar in the position of the canine and

with an otherwise functional occlusion with well-aligned teeth,

6. If there are pathologic changes (e.g., cystic formation, infection), and

7. If the patient does not desire orthodontic treatment.

Management of Impacted Canines

The most desirable approach for managing impacted maxillary canines is early

diagnosis and interception of potential impaction. However, in the absence of

prevention, clinicians should consider orthodontic treatment followed by surgical

exposure of the canine to bring it into occlusion. In such a case, open communication

between the orthodontist and oral surgeon is essential, as it will allow for the

appropriate surgical and orthodontic techniques to be used. The most common

methods used to bring palatally impacted canines into occlusion are surgically

exposing the teeth and allowing them to erupt naturally during early or late mixed

dentition and surgically exposing the teeth and placing a bonded attachment to and

using orthodontic forces to move the tooth. Three methods for uncovering a labially

impacted maxillary canine:

1. Gingivectomy,

2. Creating an apically positioned flap,

3. Using closed eruption techniques.

11

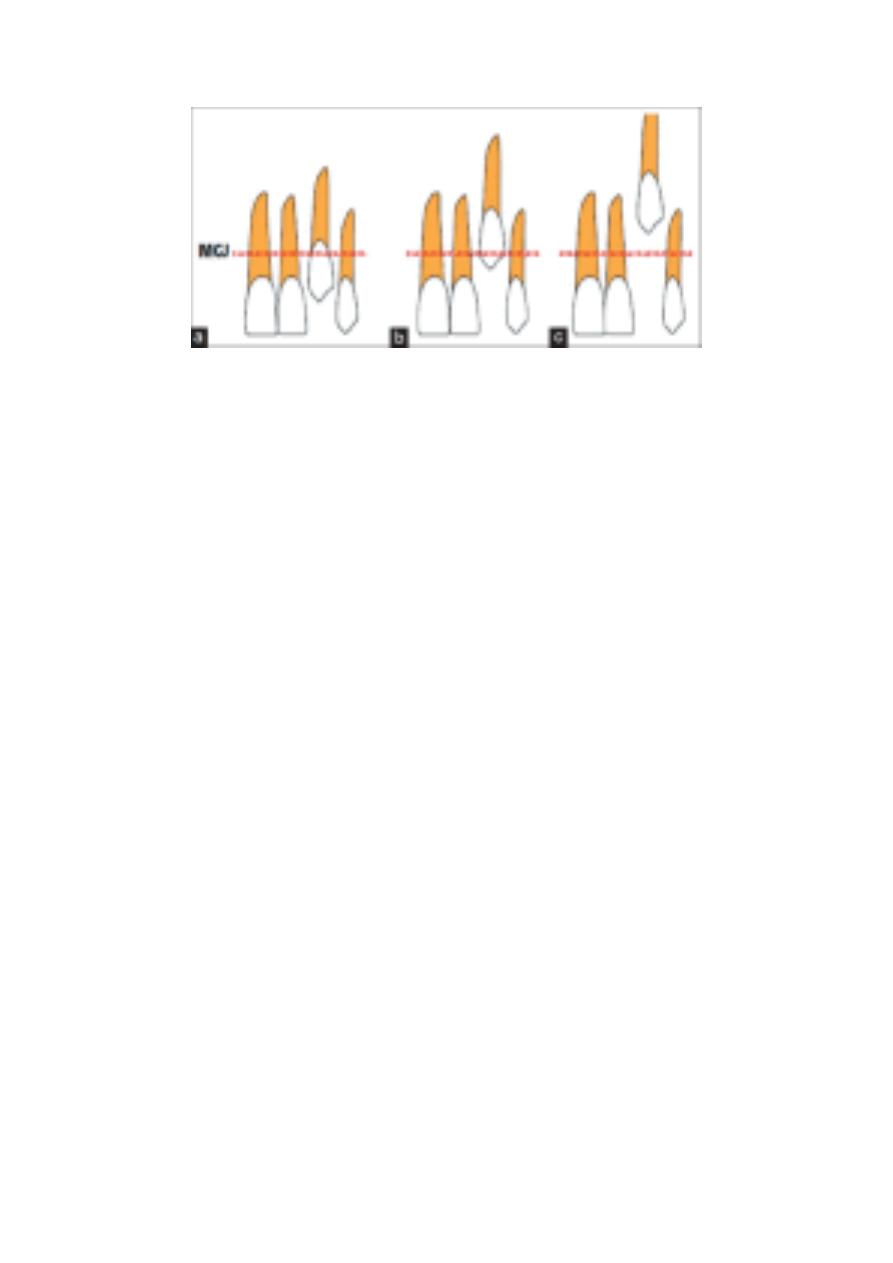

Recommended surgical techniques relative to the mucogingival junction (MGJ) when

the canine cusp is (a) coronal to the MGJ: gingivectomy; (b) apical to the MGJ:

creating an apically positioned flap; and (c) significantly apical to the MGJ: using a

closed

eruption techniques

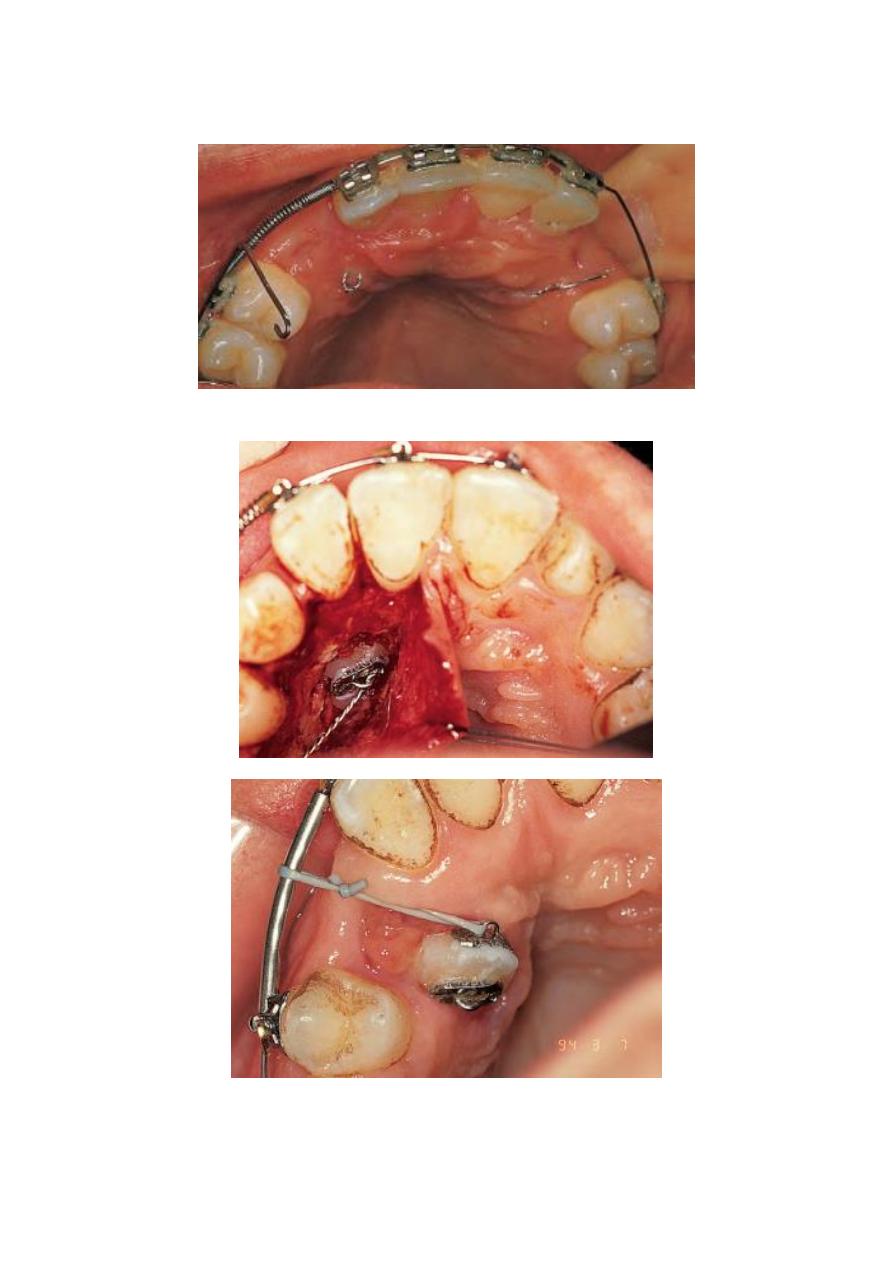

Orthodontists have recommended that other clinicians first create adequate space in

the dental arch to accommodate the impacted canine and then surgically expose the

tooth to give them access so that they can apply mechanical force to erupt the tooth.

Although various methods work, an efficient way to make impacted canines erupt is

to use closed-coil springs with eyelets, as long as no obstacles impede the path of the

canine.

If the canine is in close proximity to the incisor roots and a buccally directed force is

applied, it will contact the roots and may cause damage. In addition, the canine

position may not improve due to the root obstacle. Consequently, various techniques

have been proposed that involve moving the impacted tooth in an occlusal and

posterior direction first and then moving it buccally into the desired position. When

using a bonded attachment and orthodontic forces to bring the impacted canines into

occlusion, it is important to remember that first premolars should not be extracted

until a successful attempt is made to move the canines. If the attempt is unsuccessful,

the permanent canines should be extracted.

In such cases, the orthodontist has to decide if the premolar should be moved into the

canine position. Orthodontists should consider treatment alternatives, such as

autotransplantation or restoration, in collaboration with other specialists, including

oral surgeons, periodontists, and prosthodontists. The patient should be informed

about all of the potential complications before surgical and orthodontic interventions

take place.

11

12