Small and large intestine

ANATOMY OF THE SMALL AND LARGEINTESTINESSmall intestineThe small intestine starts at the pylorus and extends to the ileocaecal valve. It is approximately 7 m in length and is divided into the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Its main function is in thebreakdown and absorption of food products. The small bowel ispresent in the central and lower portion of the abdominal cavity.Its relations consist of the greater omentum and abdominal wallanteriorly. Posteriorly, it is fixed to the vertebral column by way ofits mesentery.The duodenum is present proximally and is about 25 cm inlength. It has no mesentery and, therefore, is the most fixed partof the small bowel.It merges into the jejunum at the duodenojejunalflexure. The remainder of the small bowel is made up ofthe jejunum and ileum. The jejunum makes up the proximal twofifths and is wider, thicker and more vascular than the ileum. It consists of circular folds of mucous membrane (valvulae conniventes) that can be used to distinguish it from the ileum. The ileum contains larger lymph node aggregates (Peyer’s patches and these can sometimes be lead points in cases of intussusception in the young.

The arterial supply of the duodenum consists of the right gastric,the superior pancreaticoduodenal branch of the hepatic artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal branch of the superior mesenteric artery. The veins drain into the superior mesenteric. The nerves are supplied from the coeliac plexus. The jejunum and ileum are vascularised by the superior mesenteric artery through a rich plexus of vessels. The veins run a similar course. The nerve supply to the small intestines arises from sympathetic nerves around the superior mesenteric artery. Pathology such as obstruction causes visceral pain, which is felt in the peri-umbilical region.

Large intestineThe large intestine extends from the ileum to the anus. The colon is approximately 1.5 m in length. It is relatively more fixed than the small bowel It also differs in that it possesses appendices epiploicae on its surface, which are peritoneal folds containing fat, and the presence of taenia, which consist of longitudinal bands of the outer muscle coat. It can be divided into the caecal, ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colonic segments.

The blood supply of the colon is derived from ileocolic, rightcolic and middle colic branches of the superior mesenteric vessels.The descending colon receives its blood supply from the leftcolic branch from the inferior mesenteric but also communicateswith the superior mesenteric system via the marginal artery ofDrummond. The veins run in a similar distribution. The nervesupply is derived from the sympathetic plexus surrounding thesuperior and inferior mesenteric arteries. Visceral pain is felt inthe peri-umbilical region in the proximal colon and in thehypogastric region in the distal colon.

FUNCTIONAL ABNORMALITIESMegacolon and non-megacolon constipationThere is no single definition of constipation; however, a bowelfrequency of less than one every 3 days would be consider abnormal by some. This group of conditions can be dividedinto:1 megacolon:a Hirschsprung’s disease;b non-Hirschsprung’s megarectum and megacolon;2 non-megacolon:a slow transit;b normal transit.

Idiopathic megarectum and megacolonThis is a rare condition and the cause is not known, although insome it may result from poor toilet training during infancy and inothers from a congenital abnormality of the intestinal myentericplexus.Clinical featuresIt presents usually in the first 20 years with severe constipation.Patients with idiopathic megarectum often present with faecalincontinence due to rectal faecal loading that requires manualevacuation. Patients with megacolon are more likely to presentwith abdominal distension and pain. On clinical examination,there may be a hard faecal mass arising out of the pelvis and, onrectal examination, there is a large faecaloma in the lumen. Theanus is usually patulous, perianal soiling is common, and sigmoidoscopy is usually impossible.

InvestigationImagingAs there is an enlarged rectum, often with distension of the colon over a variable length, a radiograph should be taken without prior bowel preparation, using a small quantity of water-soluble contrast to prevent barium impaction. There is usually gross faecal loading of the enlarged rectum and colon and, when a contrast examination is carried out, the width of the colon measured at the pelvic brim is usually more than 6.5 cm.

Anorectal physiology testsAnorectal physiology tests demonstrate delayed first sensationand raised maximum tolerated volume. Full-thickness rectal biopsy shows normal ganglion cells, a finding that definitively distinguishes this condition from Hirschsprung’s disease.

Medical treatmentThis is directed at emptying the rectum and keeping it emptywith enemas, washouts and sometimes manual evacuation under anaesthesia. Thereafter, the patient is encouraged to develop a regular daily bowel habit, with the use of osmotic laxatives to help the passage of semiformed stool.

Surgical treatmentSurgical treatment is sometimes necessary if medical therapy fails.Options that are available include:1 resection of the dilated rectum and colon back tonormal-diameter colon with normal ganglion cells confirmedby frozen section at the time of surgery, which is followed byreconstruction with a coloanal anastomosis;2 colectomy with the formation of an ileorectal anastomosis;3 restorative proctocolectomy;4 vertical reduction rectoplasty, which is a new procedure designed to reduce the volume of the rectum by at least 50%.5 stoma formation, which may be used either as a salvage operation for failure of previous surgery or as a primary intervention.

Non-megacolon constipation These are usually otherwise healthy individuals who seek help for constipation but eat a normal diet and have a normal colon on endoscopy and barium enema.Its cause is thought to involve slow whole-gut transit or arectal evacuation problem. Factors influencing bowel transit timeinclude:• drugs: opiates, anti-cholinergics and ferrous sulphate;• diseases: neurological conditions (Parkinson’s disease, multiplesclerosis and diabetic nephropathy):– hypothyroidism;– hypercalcaemia.

InvestigationWhole-gut transit time can be measured by asking the patient tostop all laxatives and take a capsule containing radio-opaquemarkers . Retention of more than 80% of the shapes,120 hours after ingestion, is abnormal.

TreatmentThis can be done in several ways:1 Dietary fibre. This is the first-line treatment for people withmild constipation. Constipation only resolves after severalweeks of therapy .2 Laxatives. It is important that patients do not fall into a cycleof laxative abuse. A number of types are available whichinclude bulk, osmotic and stimulant agents.3 Biofeedback. This involves conditioning and coordination ofthe abdominal and pelvic compartments. It has been shown tobe effective in those with a rectal evacuation problem.

VASCULAR ANOMALIES(ANGIODYSPLASIA)Capillary or cavernous haemangiomas are a cause of haemorrhagefrom the colon at any age. In the middle-aged or elderlypatient, haemangioma needs to be distinguished from other causes of sudden massive haemorrhage, such as diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis (UC) or ischaemic colitis. Angiodysplasia is a vascular malformation associated with ageing. Its true incidence is from 5 to 25% over the age of 60 years. Angiodysplasias occur particularly in the ascending colon and caecum of elderly patients. The malformations consist of dilated tortuous submucosal veins and, in severe cases, the mucosa is replaced by massive dilated deformed vessels.

Clinical featuresIn the majority, the symptoms are subtle and patients can present with anaemia. About 10–15% can have brisk bleeds, which maypresent as melaena or significant per rectum bleeding that is often intermittent.There is an association with aortic stenosis. Heyde’s syndrome describes the association of aortic valve stenosis with gastrointestinal bleeding from colonic angiodysplasia. A mild form of von Willebrand’s disease has been thought to be involved.

Investigation-Barium enema is usually unhelpful and should be avoided, because it may mask the lesion at subsequent endoscopy. -colonoscopy may show the characteristic lesion in the right colon. The lesions are only a few millimetres in size and appear as reddish, raised areas at endoscopy. ‘Pill’ endoscopy is a relatively new technology that may detect small bowel lesions. -Selective superior and inferior mesenteric angiography shows the site and extent of the lesion - a radioactive test using technetium-99m(99mTc)-labelled red cells may confirm and localise the source ofhaemorrhage.

TreatmentThe first principle is to stabilise an unstable patient. Followingthis, the bleeding needs to be localised by colonoscopy. Thisallows simple therapeutic procedures such as cauterisation to becarried out. In severe uncontrolled bleeding, surgery becomesnecessary. On-table colonoscopy is carried out to confirm the site of bleeding. Angiodysplastic lesions are sometimes demonstrated by transillumination through the caecum . If it is still not clear exactly which segment of the colon is involved, then a total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis may be necessary.

BLIND LOOP SYNDROME if a blind loop of the small intestine is made referred to as the blind loop syndrome.Essentially, the stasis produces an abnormal bacterial flora,which prevents proper breakdown of the food (especially fat) and mops up the vitamins that are present. Sometimes, the only manifestation is anaemia, resulting from vitamin B12 deficiency but, if steatorrhoea occurs, other serious malabsorption features follow. In general, high loops produce steatorrhoea, whereas lowloops tend to produce anaemia.

Temporary improvement will follow the use of antibiotics todestroy the bacteria causing the trouble, but the main treatmentis surgical excision of the cause of the stasis where applicable.

DIVERTICULAR DISEASETypesDiverticula can occur in a wide number of positions in the gut,from the oesophagus to the rectosigmoid. There are two 1- Congenital. All three coats of the bowel are present in the wall of the diverticulum, e.g. Meckel’s diverticulum.2- Acquired. The wall of the diverticulum lacks a propermuscular coat. Most alimentary diverticula are thought tobe acquired.varieties:

Duodenal diverticulaThere are two types:1 Primary. Mostly occurring in older patients on the inner wallof the second and third parts , these diverticulaare found incidentally on barium meal and are usuallyasymptomatic.2 Secondary. Diverticula of the duodenal cap result from longstanding duodenal ulceration .

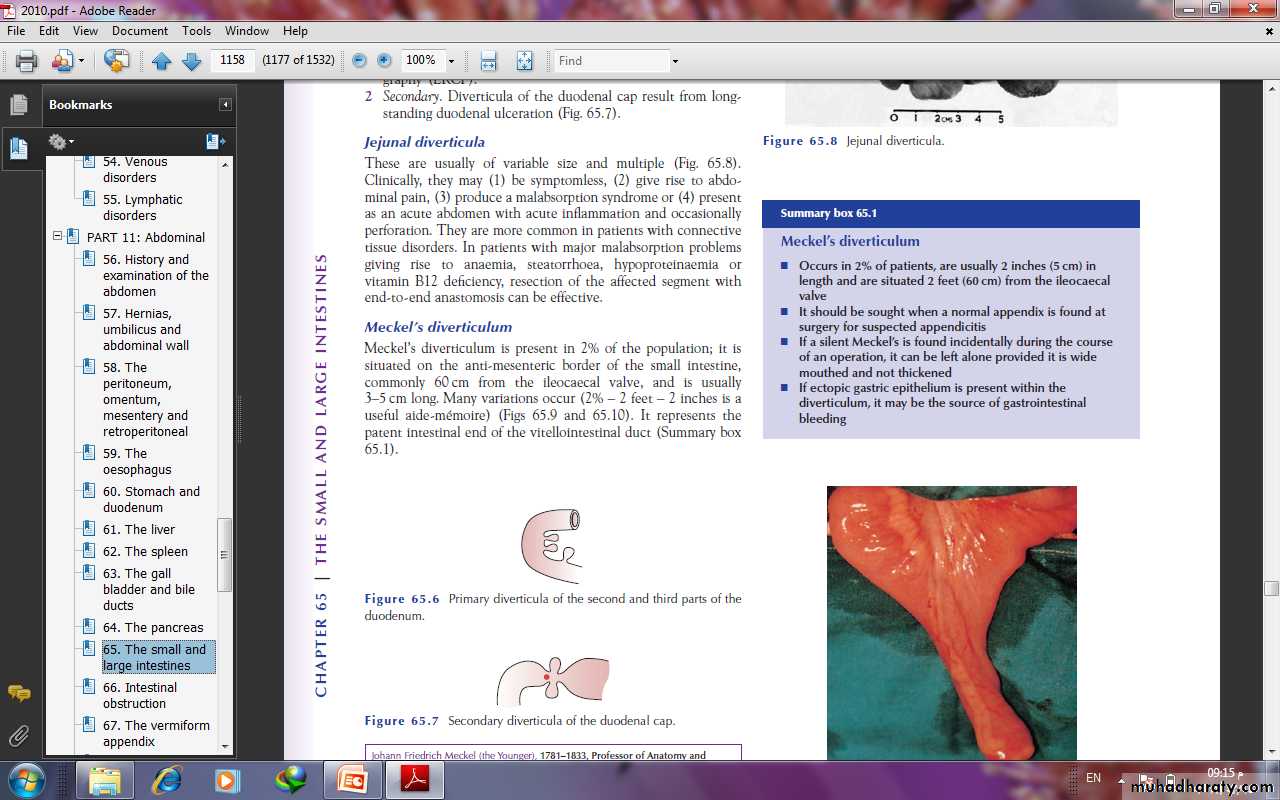

Jejunal diverticulaThese are usually of variable size and multiple (Fig. 65.8).Clinically, they may (1) be symptomless, (2) give rise to abdominalpain, (3) produce a malabsorption syndrome or (4) presentas an acute abdomen with acute inflammation and occasionallyperforation. In patients with major malabsorption problemsgiving rise to anaemia, steatorrhoea, hypoproteinaemia orvitamin B12 deficiency, resection of the affected segment withend-to-end anastomosis can be effective.

Meckel’s diverticulumMeckel’s diverticulum is present in 2% of the population; it issituated on the anti-mesenteric border of the small intestine,commonly 60 cm from the ileocaecal valve, and is usually3–5 cm long. Many variations occur (2% – 2 feet – 2 inches is auseful aide-mémoire) . It represents the patent intestinal end of the vitellointestinal duct

A Meckel’s diverticulum possesses all three coats of the intestinal wall and has its own blood supply. It is therefore vulnerable to infection and obstruction in the same way as the appendix. indeed, when a normal appendix is found at surgery for suspected appendicitis, a Meckel’s diverticulum should be sought by inspection of an appropriate length of terminal ileum. In 20% of cases, the mucosa contains heterotopic epithelium, namely gastric, colonic or sometimes pancreatic tissue. In order of frequency, these symptoms are as follows:

1 Severe haemorrhage, caused by peptic ulceration. Painlessbleeding occurs per rectum and is maroon in colour.2 Intussusception.In most cases, the apex of the intussusceptionis the swollen, inflamed, heterotopic epithelium at the mouthof the diverticulum.3 Meckel’s diverticulitis may be difficult to distinguish from thesymptoms of acute appendicitis. When a diverticulum perforates, the symptoms may simulate those of a perforated duodenal ulcer. At operation, an inflamed diverticulum should besought as soon as it has been demonstrated that the appendixand fallopian tubes are not involved.

4 Chronic peptic ulceration. As the diverticulum is part of themid-gut, the pain, although related to meals, is felt around theumbilicus.5 Intestinal obstruction. The presence of a band between the apex of the diverticulum and the umbilicus may cause obstruction either by the band itself or by a volvulus around it.

ImagingMeckel’s diverticulum can be very difficult to demonstrate bycontrast radiology; small bowel enema would be the most accurate investigation. Technetium-99m scanning may be useful in identifying Meckel’s diverticulum as a source of gastrointestinal bleeding.

‘Silent’ Meckel’s diverticulum.A Meckel’s diverticulum usually remains symptomless throughout life and is found only at necropsy. When a silent Meckel’s diverticulum is encountered in the course of an abdominal operation,it can be left provided it is wide mouthed and the wall ofthe diverticulum does not feel thickened. Where there is doubtand it can be removed without appreciable additional risk, itshould be resected.Exceptionally, a Meckel’s diverticulum is found in an inguinalor a femoral hernia sac – Littre’s hernia.

Meckel’s diverticulectomyA Meckel’s diverticulum that is broad based should not be amputated at its base and invaginated in the same way as a vermiform appendix due to risk of stricture

diverticular disease of Colon IntroductionThe prevalence of diverticular disease in the western world is60% over the age of 60 years. The condition is found in thesigmoid colon in 90% of cases, but the caecum can also beinvolved and, on occasion, the entire large bowel can be affected. The main morbidity of the disease is due to sepsis.AetiologyDiverticula of the colon are acquired herniations of colonicmucosa, protruding through the circular muscle at the pointswhere the blood vessels penetrate the colonic wall. They tend tooccur in rows between the strips of longitudinal muscle, sometimespartly covered by appendices epiploicae. The rectum withits complete muscle layers is not affected. It is thought to berelated to reduced fibre in the western diet. This results in lowstool bulk with resulting segmentation and hypertrophy of thecolonic wall musculature, thus causing increased intraluminalpressure. Diverticular disease is rare in Africans and Asians, whoeat a diet that is rich in natural fibre.

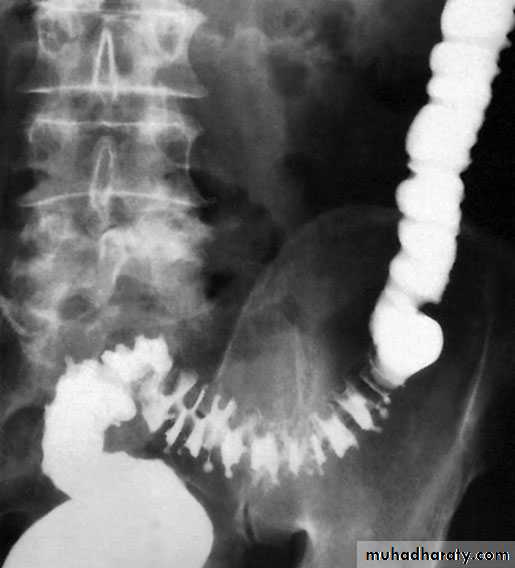

DiverticulosisIt is important to distinguish between diverticulosis, which maybe asymptomatic, and clinical diverticular disease in which thediverticula are causing symptoms. On histological investigation,the diverticulum consists of a protrusion of mucous membranescovered with peritoneum. There is thickening of the circularmuscle fibres of the intestine, which develops saw-tooth appearance on barium enema

DiverticulitisDiverticulitis is the result of inflammation of one or more diverticula,usually with some pericolitis. It is not a premalignant condition, but cancer may coexist

The complications of diverticular disease are the following:1 Recurrent periodic inflammation and pain .2 Perforation leading to general peritonitis or local (pericolic)abscess formation.3 Intestinal obstruction:a in the sigmoid as a result of progressive fibrosis causingstenosis;b in the small intestine caused by adherent loops of smallintestine on the pericolitis.4 Haemorrhage: diverticulitis may present with profuse colonichaemorrhage in 17% of cases, often requiring blood transfusions.5 Fistula formation (vesicocolic, vaginocolic, enterocolic, colocutaneous)occurs in 5% of cases, with vesicocolic being the most common.

Clinical featuresElectiveIn mild cases, symptoms such as distension, flatulence and a sensationof heaviness in the lower abdomen may be indistinguishablefrom those of irritable bowel syndrome.EmergencyPersistent lower abdominal pain, usually in the left iliac fossa,with or without peritonitis, could be caused by diverticulitis.Fever, malaise and leucocytosis can differentiate diverticulitisfrom painful diverticulosis. The patient may pass loose stools ormay be constipated; the lower abdomen is tender, especially onthe left, but occasionally also in the right iliac fossa if the sigmoidloop lies across the midline. The sigmoid colon is often palpable,tender and thickened. Rectal examination may, but does not usually,reveal a tender mass. Any urinary symptoms may herald theformation of a vesicocolic fistula, which leads to pneumaturia(flatus in the urine) and even faeces in the urine.

1 Pericolic abscess or phlegmon 2 Pelvic or intra-abdominal abscess 3 Non-faeculent peritonitis 4 Faeculent peritonitis

Classification of diverticulitis (Hinchey)

DiagnosisRadiologyAlthough the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is made on clinicalgrounds, it can be confirmed during the acute phase by computerised tomography (CT). It is particularly good at identifyingbowel wall thickening, abscess formation and extraluminal disease., drainage may be carried out percutaneously. Such anoption may delay or postpone further operative procedures.

Barium enemas and sigmoidoscopy are usuallyreserved for patients who have recovered from an attack of acute diverticulitis, for fear of causing perforation or peritonitis. Watersoluble contrast enemas may, however, be helpful in sorting out patients with large bowel obstruction. In the acute situation, it is good at detecting intraluminal changes and leakage. The sensitivity for this is of the order of 90%. Barium radiology is carried out to exclude a carcinoma and to assess the extent of the disease.

Where the sigmoid colon is thickened and narrowed, a ‘sawtooth’ appearance may be seen. Some strictures can be very difficult to distinguish by radiology alone and, in those circumstances, colonoscopy will be necessary to rule out a carcinoma. Vesicocolic fistulae should be evaluated with cystoscopy and biopsy in addition to colonoscopy. Contrast examinations may show the fistula itself. The differential diagnosis for vesicocolic fistulae (and other fistulae) includes cancer, radiation damage, Crohn’s disease (CD), tuberculosis and actinomycosis.

ColonoscopyColonoscopy may reveal the necks of diverticula within the bowel lumen . The differential diagnosis from a carcinoma can beimpossible if a tight stenosis prevents colonoscopy. In equivocalcases, biopsies may be taken

ManagementNon-complicatedDiverticulosis should be treated with a high-residue diet containing bread, flour, fruit and vegetables. Bulkformers such as bran, Isogel and Fybogel may be given

until the stools are soft. Painful diverticular disease may requireantispasmodics.Acute diverticulitis is treated by bed rest and intravenousantibiotics (usually cefuroxime and metronidazole).

Operative procedures for diverticular diseaseThe aim of surgery is to control sepsis in the peritoneum and circulation.Indications for operation include general peritonitis andfailure to resolve on conservative treatment. Postoperative mortality and reoperation rate for elective resection are 5% and 12%, respectively

The ideal operation carried out as after careful preparation of the gut is a one-stage resection. This involves removal of the affected segment and restoration of continuity by end-to-end anastomosis

If there is obstruction, inflammatory oedema and adhesions orthe bowel is loaded with faeces, a Hartmann’s operation is theprocedure of choice

In acute perforation, peritonitis soon becomes general andmay be purulent, with a mortality rate of about 15%. Grossfaecal peritonitis carries a mortality rate of more than 50% andpneumoperitoneum is usually present; the diagnosis may notbe confirmed until emergency laparotomy. There is a choice ofprocedures:a primary resection and Hartmann’s procedure ;b primary resection and anastomosis after on-table lavage inselected cases;c exteriorisation of the affected bowel, which is then openedas a colostomy, a procedure now rarely used. Fistulae can be cured only by resection of the diseased boweland closure of the fistula. In the case of a colovesical fistula

Haemorrhage from diverticulitis must be distinguished fromangiodysplasia. It usually responds to conservative managementand occasionally requires resection On-table lavage andcolonoscopy may be necessary to localise the bleeding site. Ifthe source cannot be located, then subtotal colectomy andileostomy is the safest option..

Solitary diverticulum of the caecum and ascending colon is rareand congenital, and may present with symptoms and signs identical to those of acute appendicitis

Hirschsprung’s diseaseHirschsprung’s disease is characterised by the congenital absence of intramural ganglion cells and the presence of hypertrophicnerves in the distal large bowel. The affected gut is tonically contracted causing functional bowel obstruction. The aganglionosis is restricted to the rectum and sigmoid colon in 75% of patients (short segment), involves the proximal colon in 15% (long segment) and affects the entire colon

and a portion of terminal ileum in 10% (total colonic aganglionosis).A transition zone exists between the dilated, proximal, normallyinnervated bowel and the narrow, distal aganglionic segment.Hirschsprung’s disease may be familial or associated withDown’s syndrome or other genetic disorders. Gene mutations havebeen identified on chromosome 10 and on chromosome 13 in some patients

Hirschsprung’s disease typically presents in the neonatal period with delayed passage of meconium, abdominal distension and bilious vomiting but it may not be diagnosed until later in childhood or even adult life, when it manifests as severe chronic constipation.Enterocolitis is a potentially fatal complication of the disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease depends on histological examination of an adequate rectal biopsy by an experienced pathologist. A contrast enema may show the extent of the aganglionic segment

TreatmentSurgery aims to remove the aganglionic segmentand bring down healthy ganglionic bowel to the anus; these‘pull-through’ operations (e.g. Swenson, Duhamel, Soave andtransanal procedures) can be done in a single stage or in several stages after first establishing a proximal stoma in normally innervated bowel.

ULCERATIVE COLITISAetiologyThe cause of UC is unknown. There is probably a genetic contribution with no clear Mendelian pattern of inheritance. It has been shown that 15% of patients with UC have a first-degree relative with inflammatory bowel disease. UC is more common inCaucasians than in blacks or Asians. In spite of intensive bacteriological studies, no organisms or group of organisms can be incriminated. Smoking seems to have a protective effect

UC is thought to be an immune disorder in individuals with yet unknown susceptibility genes or a hypersensitivity reaction to an external antigen.

EpidemiologyThe disease has been rare in eastern populationsbut is now being reported more commonly, suggesting an environmental cause that has developed as a result of an increasing ‘westernisation’ of diet and/or social habits and better diagnostic facilities. The sex ratio is equal in the first four decades of life. from the age of 40 years, the incidence in females falls whereas it remains the same in males. It is uncommon before the age of 10 years, and most patients are between the ages of 20 and 40 years at diagnosis.

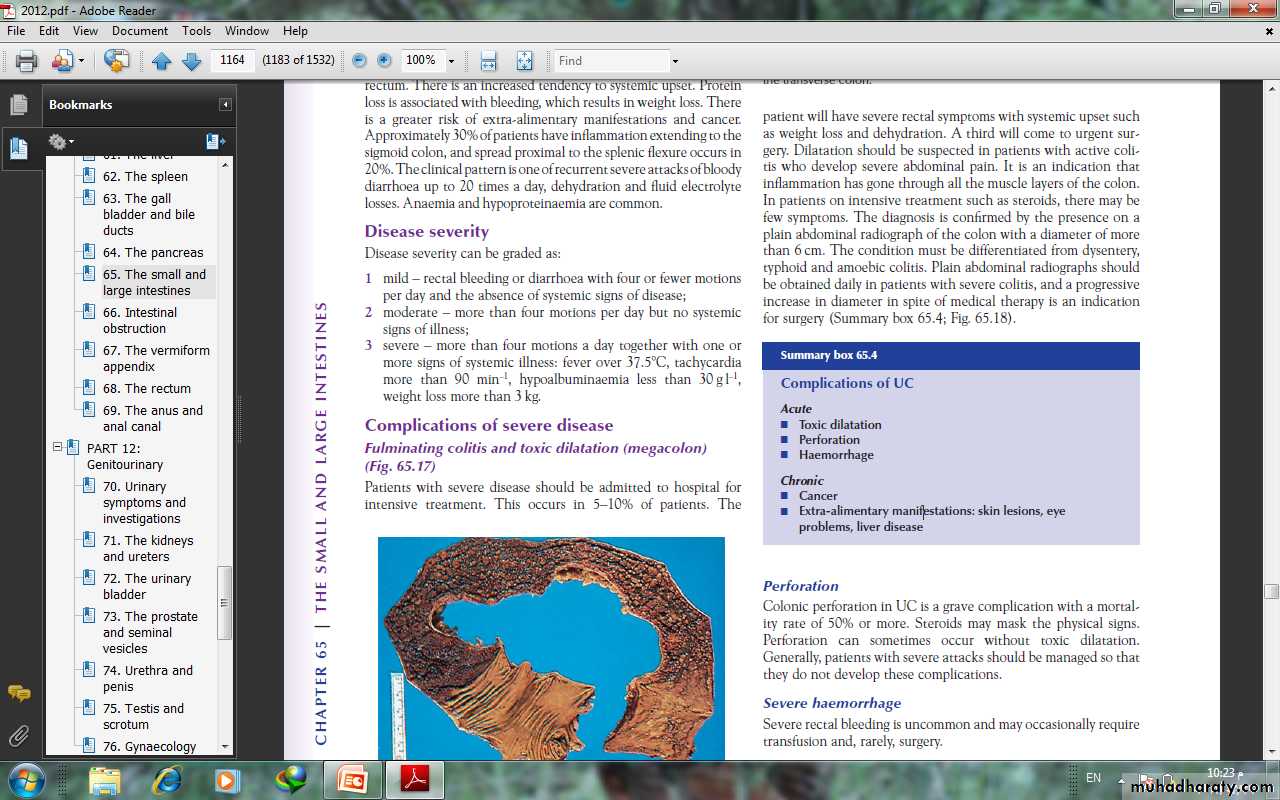

PathologyIn 95% of cases, the disease starts in the rectum and spreadsproximally. The rectum is involved in all circumstances . It is a diffuse inflammatory disease, primarily affecting the mucosa andsuperficial submucosa, and only in severe disease are the deeperlayers of the intestinal wall affected. There are multiple minuteulcers.

When the disease is chronic, inflammatory polyps(pseudopolyps) occure and may be numerous.In severe fulminant colitis, a section of the colon, usuallythe transverse colon, may become acutely dilated, with the risk ofperforation (‘toxic megacolon’). On microscopic investigation,there is an increase in inflammatory cells in the lamina propria,the walls of crypts are infiltrated by inflammatory cells and thereare crypt abscesses. There is depletion of goblet cell mucin. Withtime, these changes become severe, and precancerous changescan develop (= severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ).

SymptomsThe first symptom is watery or bloody diarrhoea; there may be arectal discharge of mucus that is either blood-stained or purulent.Pain as an early symptom is unusual

In most cases, the disease is chronic and characterised by relapses and remissions. In general,a poor prognosis is indicated by (1) a severe initial attack, (2) disease involving the whole colon (3) increasing age, especially after 60 years.

ProctitisAs most of the colon ishealthy, the stool is formed or semiformed, and the patient isoften severely troubled by tenesmus and urgency andextra-alimentary manifestations are rare.

Colitis Diarrhoea usually implies that there is active disease proximal to the rectum. There is an increased tendency to systemic upset. Protein loss is associated with bleeding, which results in weight loss. There is a greater risk of extra-alimentary manifestations and cancer. The clinical pattern is one of recurrent severe attacks of bloody diarrhoea up to 20 times a day, dehydration and fluid electrolyte losses. Anaemia and hypoproteinaemia are common.

Disease severityDisease severity can be graded as:1 mild – rectal bleeding or diarrhoea with four or fewer motionsper day and the absence of systemic signs of disease;2 moderate – more than four motions per day but no systemicsigns of illness;3 severe – more than four motions a day together with one ormore signs of systemic illness: fever over 37.5°C, tachycardiamore than 90 min–1, hypoalbuminaemia less than 30 g l–1,weight loss more than 3 kg.

Complications of severe diseaseFulminating colitis and toxic dilatation (megacolon)Patients with severe disease should be admitted to hospital forintensive treatment. This occurs in 5–10% of patients. Thepatient will have severe rectal symptoms with systemic upset suchas weight loss and dehydration. In patients on intensive treatment such as steroids, there may befew symptoms. The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence on aplain abdominal radiograph of the colon with a diameter of morethan 6 cm. The condition must be differentiated from dysentery,typhoid and amoebic colitis. Plain abdominal radiographs shouldbe obtained daily in patients with severe colitis, and a progressiveincrease in diameter in spite of medical therapy is an indicationfor surgery

PerforationColonic perforation in UC is a grave complication with a mortalityrate of 50% or more Severe haemorrhageSevere rectal bleeding is uncommon and may occasionally requiretransfusion and, rarely, surgery

InvestigationsA plain abdominal film can often show the severity of disease.Faeces are present only in parts of the colon that are normal oronly mildly inflamed. Mucosal islands can sometimes be seen.

Barium enemaThe principal signs are :• loss of haustration, especially in the distal colon;• mucosal changes caused by granularity;• pseudopolyps;• in chronic cases, a narrow contracted colon.

SigmoidoscopySigmoidoscopy is essential for diagnosis of early cases and milddisease not showing up on a barium enema. The initial findingsare those of proctitis: the mucosa is hyperaemic and bleeds ontouch, and there may be a pus-like exudate. Where there hasbeen remission and relapse, there may be the presence of pseudopolyps. Later, tiny ulcers may be seenthat appear to coalesce. This is different from the picture ofamoebic dysentery, in which there are large, deep ulcers withintervening normal mucosa.

Colonoscopy and biopsyThis has an important place in management:1 to establish the extent of inflammation;2 to distinguish between UC and Crohn’s colitis;3 to monitor response to treatment;4 to assess longstanding cases for malignant change

Bacteriology A stool specimen needs to be sent for microbiology analysis when UC is suspected. Other infective causes include Shigella and amoebiasis.Pseudomembranous colitis occurs in hospital patients on antibiotictreatment and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAIDs). The causative organism is Clostridium difficile.Immunocompromised patients are at risk of infective proctocolitisfrom cytomegalovirus and cryptosporidia

Extraintestinal manifestationsArthritis occurs in around 15% of patients and is of the large jointpolyarthropathy type, affecting knees, ankles, elbows and wrists.Sacroiliitis and ankylosing spondylitis are 20 times more commonin patients with UC.Bile duct cancer is a rare complication, and colectomy does not

• skin lesions: erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum or aphthous ulceration;• eye problems: iritis;• liver disease: sclerosing cholangitis has been reported in up to70% of cases. Diagnosis is by ERCP, which demonstrates thecharacteristic alternating stricturing and bleeding of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts.

TreatmentMedical treatment of an acute attackCorticosteroids are the most useful drugs and can be given eitherlocally for inflammation of the rectum or systemically when thedisease is more extensive. One of the 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives can be given both topically and systemically.Their main function is in maintaining remission rather thantreating an acute attack. Non-specific anti-diarrhoeal agentshave no place in the routine management of UC

Mild attacksPatients with a mild attack will usually respond torectally administered steroids or oral prednisolone 20 mg day–1 is given over a 3- to 4-week period.One of the 5-ASA compounds should be given concurrently.Moderate attacksThese patients should be treated with oral prednisolone 40 mgday–1, twice-daily steroid enemas and 5-ASA.

Severe attacksThese patients must be regarded as medical emergencies andrequire immediate admission to hospital. It is important to monitor vital signs (pulse, temperature andblood pressure). A stool chart should be kept.Increasing abdominal girth is a potential sign of megacolon developing.A plain abdominal radiograph is taken daily and inspectedfor dilatation of the transverse colon of more than 5.5 cm.

The presence of mucosal islands or intramural gas on plain radiographs increasing colonic diameter or a sudden increasein pulse and temperature may indicate a colonic perforation. Fluidand electrolyte balance is maintained, anaemia is corrected andadequate nutrition is provided, parenteral nutrition may be indicated.The patient is treated with intravenous hydrocortisone100–200 mg four times daily.

There is no evidence that antibiotics modify the course of a severe attack. Some patients are treated with azathioprine or ciclosporin A to induce remission. If there is failure to gain an improvement within 3–5 days, then surgery must be seriously considered. Prolonged high-dose intravenous steroid therapy is fraught with danger.

Indications for surgery :• severe or fulminating disease failing to respond to medicaltherapy;• chronic disease with anaemia, frequent stools, urgency andtenesmus;• steroid-dependent disease – here, the disease is not severe butremission cannot be maintained without substantial doses ofsteroids;• the risk of neoplastic change: patients who have severe dysplasiaon review colonoscopy;• extraintestinal manifestations;• rarely, severe haemorrhage or stenosis causing obstruction.

Operations--the ‘first aid procedure’ is a total abdominal colectomy and ileostomy. This has the advantagethat the patient recovers quickly, the histology of the resectedcolon can be checked, and restorative surgery can be contemplatedat a later date.--Proctocolectomy and ileostomyThis is the procedure associated with the lowest complicationrate. It is indicated in patients who are not candidates for restors.

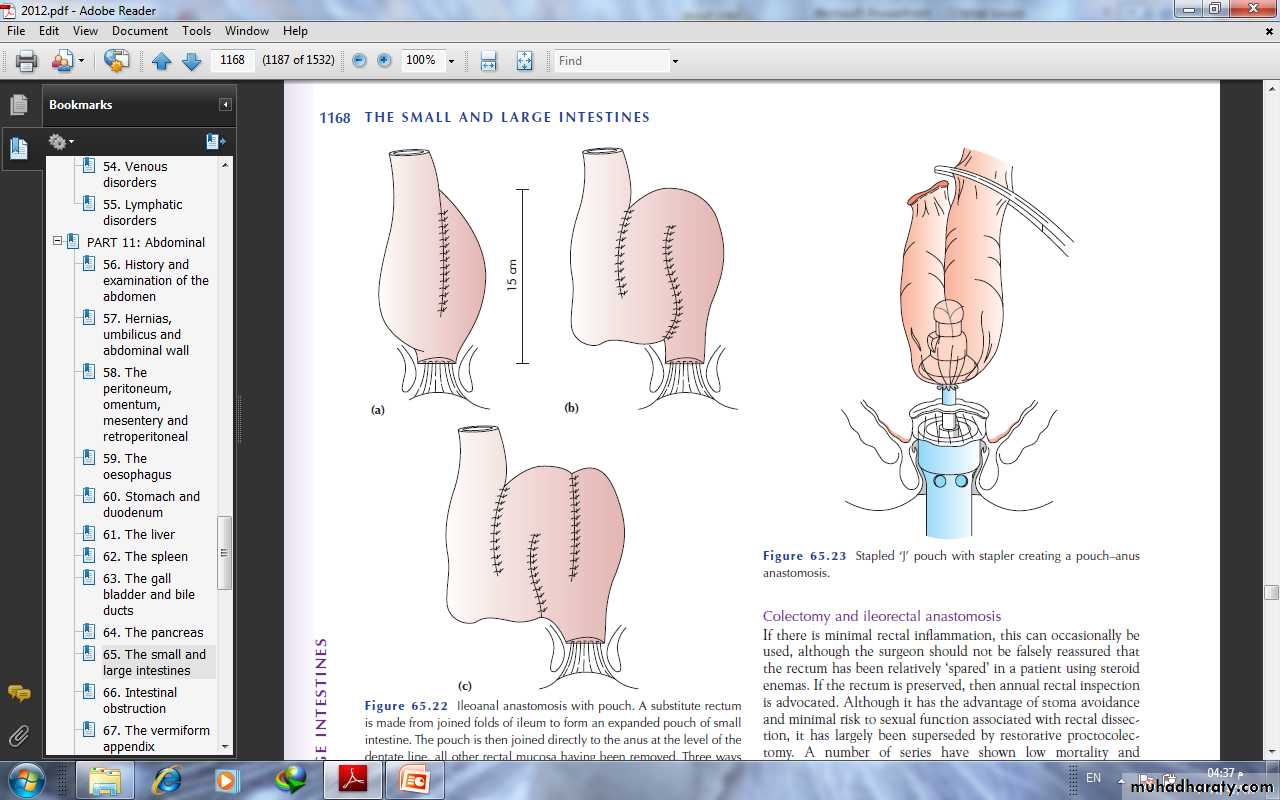

--Restorative proctocolectomy with an ileoanal pouch (Parks)In this operation, a pouch is made out of ileum as asubstitute for the rectum and sewn or stapled to the anal canal.This avoids a permanent stoma.

--Colectomy and ileorectal anastomosisIf there is minimal rectal inflammation, this can occasionally beused, although the surgeon should not be falsely reassured thatthe rectum has been relatively ‘spared’ in a patient using steroidenemas

Ileostomy with a continent intra-abdominal pouch (Kock’sprocedure)A reservoir is made from 30 cm of ileum and, just beyond this, aspout is made by inverting the efferent ileum into itself to give acontinent valve just below skin level.

CROHN’S DISEASE (REGIONAL ENTERITIS) It can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the lips to the anal margin, but ileocolonic disease is the most common presentation.

EpidemiologyIt is most common in North America and northern Europe withan incidence of 5 per 100 000. It is slightly more common in women than in men, but is most commonly diagnosed in young patients between the ages of 25 and 40 years.

AetiologyAlthough CD has some features suggesting chronic infection, nocausative organism has ever been found; similarities between CDand tuberculosis have focused attention on mycobacteria. Studieshave found DNA of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis in the intestinesof 60% of patients with CD . However, no immunology reaction has been detected against this organism, and anti-tuberculosis treatment has no effect. Focal ischaemia has also been postulated as a causative factor, possibly originating from a vasculitis arising through an immunological process. Smoking increases the risk.

Genetic factors are thought to play a part. About 10% ofpatients have a first-degree relative with the disease. There is an association with ankylosing spondylitis. As withUC, it is now believed that CD can predispose to cancer .

PathogenesisAs in UC, there is thought to be an increased permeability of themucous membrane. This leads to increased passage of antigens,which are thought to induce a cell-mediated inflammatoryresponse. This results in the release of cytokines, such as interleukin- 2 and tumour necrosis factor, which coordinate local and systemic responses. In CD, there is thought to be a defect in suppressor T cells.

PathologyIleal disease is the most common, accounting for 60% of cases;30% of cases are limited to the large intestine, and the remainderare in patients with ileal disease alone or more proximal smallbowel involvement. Anal lesions are common. CD of the mouth,oesophagus, stomach and duodenum is uncommon.

Resection specimens show a fibrotic thickening of the intestinal wall with a narrow lumen. There is usually dilated gut just proximal to the stricture and, in the strictured area, there are deep mucosal ulcerations with linear or snake-like patterns. Oedema in the mucosa between the ulcers gives rise to a cobblestone appearance.

The transmural inflammation leads to adhesions,inflammatory masses with mesenteric abscesses and fistulae intoadjacent organs.

mesenteric lymph nodes are enlarged. The condition is discontinuous, with inflamed areas separated fromnormal intestine, so called skip lesions. There are non-caseating giant cell granulomas, but these are only found in 60% of patients.

Clinical featuresPresentation depends upon the area of involvement.Acute Crohn’s diseaseAcute CD occurs in only 5% of cases. Symptoms and signs resemblethose of acute appendicitis, but there is usually diarrhoea preceding the attack. Acute colitis with or without toxic megacolon can occur in CD but is less common than in UC.

Chronic Crohn’s diseaseThere is often a history of mild diarrhoea extending over manymonths, occurring in bouts accompanied by intestinal colic.Patients may complain of pain, particularly in the right iliac fossa,and a tender mass may be palpable. Intermittent fevers, secondaryanaemia and weight loss are common. A perianal abscess orfissure may be the first presenting feature of CD.After months of repeated attacks with acute inflammation,the affected area of intestine begins to narrow with fibrosis,causing obstructive symptoms.With progression of the disease, adhesions and transmural fissuring,intra-abdominal abscesses and fistula tracts can develop.1 Enteroenteric fistulae can occur into adjacent small bowel loopsor the pelvic colon, and enterovesical fistulae may causerepeated urinary tract infections and pneumaturia.2 Enterocutaneous fistulae rarely occur spontaneously andusually follow previous surgery.

InvestigationLaboratoryA full blood count needs to be performed to exclude anaemia.There is usually a fall in albumin, magnesium, zinc and selenium,especially in active disease. Protein levels that correspondto disease activity include C-reactive protein.

EndoscopySigmoidoscopic examination may be normal or show minimalinvolvement. However, ulceration in the anal canal will bereadily seen. As a result of the discontinuous nature of CD, there will beareas of normal colon or rectum. In between these, there areareas of inflamed mucosa that are irregular and ulcerated, with amucopurulent exudate

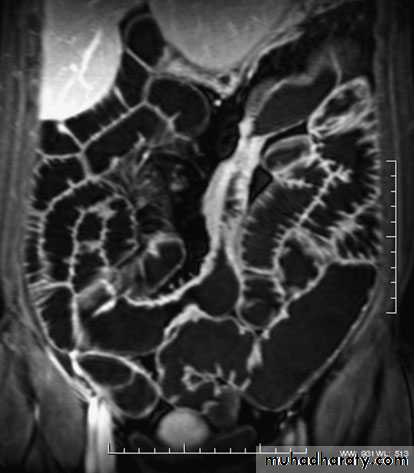

ImagingBarium enema will show similar features to those of colonoscopyin the colon. The best investigation of the small intestine is smallbowel enema . This will show up areas of delay anddilatation. The involved areas tend to be narrowed, irregular and,sometimes, when a length of terminal ileum is involved, theremay be the string sign of Kantor. Sinograms are useful in patientswith enterocutaneous fistulae. CT scans are used in patients withfistulae and those with intra-abdominal abscesses and complexinvolvement .Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to be usefulin assessing perianal disease.

TreatmentMedical therapySteroidsSteroids are the mainstay of treatment. These are effective ininducing remission in moderate to severe disease in 70–80% ofcases. Steroids can also be used as topical agents in the rectumwith reduced systemic bioavailability, but long-term use causesadrenal suppression. They are better at inducing remission thanmesalamine but has no role in maintenance. Patients suffering arelapse are treated with up to 40 mg of prednisolone orally daily,supplemented by 5-ASA compounds in those patients withcolonic involvement.

AntibioticsThose who have symptoms and signs of a mass or an abscessare also treated with antibiotics. Metronidazole is used,especially in perianal disease.Immunomodulatory agentsAzathioprine is used for its additive and steroid-sparing effectand is now standard maintenance therapy. It is a purine analogueCiclosporin acts by inhibiting cell-mediatedimmunity. Short-course intravenous treatment is associated with80% remission

Monoclonal antibodyInfliximab, the monoclonal antibody directedtowards tumour necrosis factor alpha, given to the patients withsevere, active disease who are refractory to ‘conventional’ treatments

Indications for surgerySurgical resection will not cure CD. Surgery is therefore focusedon the complications of the disease. These complications include:• recurrent intestinal obstruction;• bleeding;• perforation;• failure of medical therapy;• intestinal fistula;• fulminant colitis;• malignant change;• perianal disease.

SurgeryThe course of the disease after surgery is unpredictable, butrecurrence is common.1 Ileocaecal resection is the usual procedure for ileocaecal diseasewith a primary anastomosis between the ileum and theascending or transverse colon2 Segmental resection. Short segments of small or large bowelinvolvement can be treated by segmental resection3 Colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis4 Emergency colectomy5 Laparoscopic surgery.6 Temporary loop ileostomy.7 Proctocolectomy8 Strictureplasty9 Anal disease

Differences between UC and CD■ UC affects the colon; CD can affect any part of thegastrointestinal tract, but particularly the small and largebowel■ UC is a mucosal disease whereas CD affects the fullthickness of the bowel wall■ UC produces confluent disease in the colon and rectumwhereas CD is characterised by skip lesions■ CD more commonly causes stricturing and fistulation■ Granulomas may be found on histology in CD but not in UC■ CD is often associated with perianal disease whereas this isunusual in UC■ CD affecting the terminal ileum may produce symptomsmimicking appendicitis, but this does not occur in UC■ Resection of the colon and rectum cures the patient withUC, whereas recurrence is common after resection in CD

INFECTIONSIntestinal amoebiasisAmoebiasis is an infestation with Entamoeba histolytica. This parasitehas a worldwide distribution and is transmitted mainly incontaminated drinking water.PathologyThe ulcers, which have been described as ‘bottlenecked’ becauseof their considerably undermined edges, have a yellow necroticfloor, from which blood and pus exude. BiopsyEndoscopic biopsies or fresh hot stools are examined carefully tolook for the presence of amoebae.

Clinical featuresDysentery is the principal manifestation of the disease, but it maycome in various other presentations include =Appendicitis or amoebic caecal mass.. to operate on a patient with amoebic dysentery without precautions may prove fatal=Perforation.. the most common sites are the caecum and rectosigmoid.=Severe rectal haemorrhage as a result of separation of theslough is liable to occur.=Granuloma.. progressive amoebic invasion of the wall of the rectum or colon,with secondary inflammation, can produce a granulomatous massindistinguishable from a carcinoma.=Ulcerative colitis .. search for amoebae should always be made in the stools ofpatients believed to have UC.=Fibrous stricture may follow the healing of extensive amoebic ulcers.= Intestinal obstruction is a common complication of amoebiasis.= Paracolic abscess, ischiorectal abscess and fistula occur fromperforation by amoebae of the intestinal wall followed by secondaryinfection.

TreatmentMetronidazole (Flagyl) is the first-line drug, 800 mgthree times daily for 7–10 days. Diloxanide furoate is best forchronic infections associated with the passage of cysts in stools.Intestinal antibiotics improve the results of the chronic stages,probably by coping with superadded infection.

Typhoid and paratyphoidTyphoidParalytic ileus is the most common complication of typhoid.Intestinal haemorrhage may be the leading symptom. Othersurgical complications of typhoid and parathyroid include:• haemorrhage;• perforation;• cholecystitis;• phlebitis;• genitourinary inflammation;• arthritis;• osteomyelitis.Typhoid ulcerPerforation of a typhoid ulcer usually occurs during the thirdweek . The ulcer is parallel to the long axis of the gut and is usually situated in thelower ileum.Paratyphoid BPerforation of the large intestine sometimes occurs in paratyphoidB infection;

Tuberculosis of the intestineTuberculosis can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract fromthe mouth to the anus. The sites affected most often are theileum, proximal colon and peritoneum. There are two principaltypes.Ulcerative tuberculosisUlcerative tuberculosis is secondary to pulmonary tuberculosisand arises as a result of swallowing tubercle bacilli. There aremultiple ulcers in the terminal ileum, lying transversely, and theoverlying serosa is thickened, reddened and covered in tubercles.Clinical featuresDiarrhoea and weight loss are the predominant symptoms, andthe patient will usually be receiving treatment for pulmonarytuberculosis.

RadiologyA barium meal and follow-through or small bowel enema willshow the absence of filling of the lower ileum, caecum and mostof the ascending colon as a result of narrowing.TreatmentA course of chemotherapy is given. Healing often occursprovided the pulmonary tuberculosis is adequately treated. Anoperation is only required in the rare event of a perforation orintestinal obstruction.

Hyperplastic tuberculosisThis usually occurs in the ileocaecal region, although solitary andmultiple lesions in the lower ileum are sometimes seen. This iscaused by the ingestion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by patients.

Clinical featuresAttacks of abdominal pain with intermittent diarrhoea are theusual symptoms. The ileum above the partial obstruction is distended,and the stasis and consequent infection lead to steatorrhoea,anaemia and loss of weight. Sometimes, the presentingpicture is of a mass in the right iliac fossa in a patent with vagueill health. The differential diagnosis is that of an appendix mass,carcinoma of the caecum, CD, tuberculosis or actinomycosis ofthe caecum.

RadiologyA barium follow-through or small bowel enema will show a longnarrow filling defect in the terminal ileum.TreatmentWhen the diagnosis is certain and the patient has not yet developedobstructive symptoms, treatment with chemotherapy isadvised and may cure the condition. Where obstruction is present,operative treatment is required and ileocaecal resection is indicated .

Actinomycosis of the ileocaecal regionAbdominal actinomycosis is rare. Unlike intestinal tuberculosis,narrowing of the lumen of the intestine does not occur andmesenteric nodes do not become involved. However, a localabscess spreads to the retroperitoneal tissues and the adjacentabdominal wall, becoming the seat of multiple indurated discharging sinuses.

Clinical featuresThe usual history is that appendicectomy has been carried out foran appendicitis. Some 3 weeks after surgery, a mass is palpable inthe right iliac fossa and, soon afterwards, the wound begins to discharge.At first, the discharge is thin and watery, but later itbecomes thicker and malodorous. Pus should be sent for bacteriologicalexamination, which will reveal the characteristic sulphurgranules.TreatmentPenicillin or cotrimoxazole treatment should be prolonged and inhigh dosage.

TUMOURS OF THE SMALL INTESTINECompared with the large intestine, the small intestine is rarelyBenignAdenomas, submucous lipomas and gastrointestinal stromaltumours (GISTs) occur from time to time, and sometimes revealthemselves by causing an intussusception. The second most commoncomplication is intestinal bleeding from an adenoma, inwhich event the diagnosis is frequently long delayed because thetumour is overlooked at barium radiology, endoscopy and evensurgery.Peutz–Jeghers syndromeThis is an autosomal dominant disease. This consists of:• intestinal hamartomatosis is a polyposis affecting the whole ofthe small bowel and colon, where it is a cause of haemorrhageand often intussusception;• melanosis of the oral mucous membrane and the lips.

Long-term follow-up of patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndromehas shown reduced survival secondary to complications of recurrentbowel cancer and the development of a wide range of cancers.These include colorectal, gastric, breast, cervical, ovarian,

HistologyThe polyps can be likened to trees. The trunk and branches aresmooth muscle fibres and the foliage is virtually normal mucosa.TreatmentAs malignant change rarely occurs, resection is only necessary forserious bleeding or intussusception. Large single polyps can beremoved by enterotomy, or short lengths of heavily involvedintestine can be resected. The incidence of further lesions developing problems in the future can be reduced by thorough intraoperative examination at the time of the first laparotomy. Using on-table enteroscopy, polyps suitable for removal can be identified.Those lesions within reach can be snared by colonoscopy.

Malignant--LymphomaThere are three main types, as follows:1 Western-type lymphoma.They are now thought to benon-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma in origin. They may presentwith obstruction and bleeding, perforation, anorexia andweight loss.2 Primary lymphoma associated with coeliac disease.this is now regarded as a T-cell lymphoma. Worsening ofthe patient’s diarrhoea, with pyrexia of unknown origintogether with local obstructive symptoms.3 Mediterranean lymphoma. This is found mostly in North Africaand the Middle East and is associated with α-chain disease.Unless there are particular surgical complications these conditionsare usually treated with chemotherapy.--CarcinomaLike small bowel tumours, these can present with obstruction,bleeding or diarrhoea. Complete resection offers the only hope of cure

Carcinoid tumourThese tumours occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract, mostcommonly in the appendix, ileum and rectum in decreasing orderof frequency. They arise from neuroendocrine cells at the base ofintestinal crypts. The primary is usually small but, when theymetastasise, the liver is usually involved; when this has occurred, the carcinoid syndrome will become evident.The tumours can produce a number of vasoactive peptides, mostcommonly 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), which may be presentas 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the urine duringattacks.

The clinical syndrome itself consists of reddish-blue cyanosis,flushing attacks, diarrhoea, borborygmi, asthmatic attacks and,eventually, sometimes pulmonary and tricuspid stenosis.Classically, the flushing attacks are induced by alcohol.

TreatmentMost patients with gastrointestinal carcinoids do not have carcinoid syndrome. Surgical resection is usually sufficient. In thecases found incidentally at appendicectomy, nothing further isrequired. In patients with metastatic disease, multiple enucleationsof hepatic metastases or even partial hepatectomy can becarried out. The treatment has been transformed by the use ofoctreotide (a somatostatin analogue)

Gastrointestinal stromal tumoursThese tumours can be either benign or malignant. Increasedsize is associated with malignant potential. GIST is a type ofsarcoma that develops from connective tissue cells. It is foundmost commonly in the stomach but can be found in other sitesof the gut. It occurs most commonly in the 50- to 70-year agegroup.

SymptomsPatients may be asymptomatic. Other symptoms include lethargy,pain, nausea, haematemesis or melaena.Treatment Surgery is the most effective way of removing GISTs as they are radioresistant

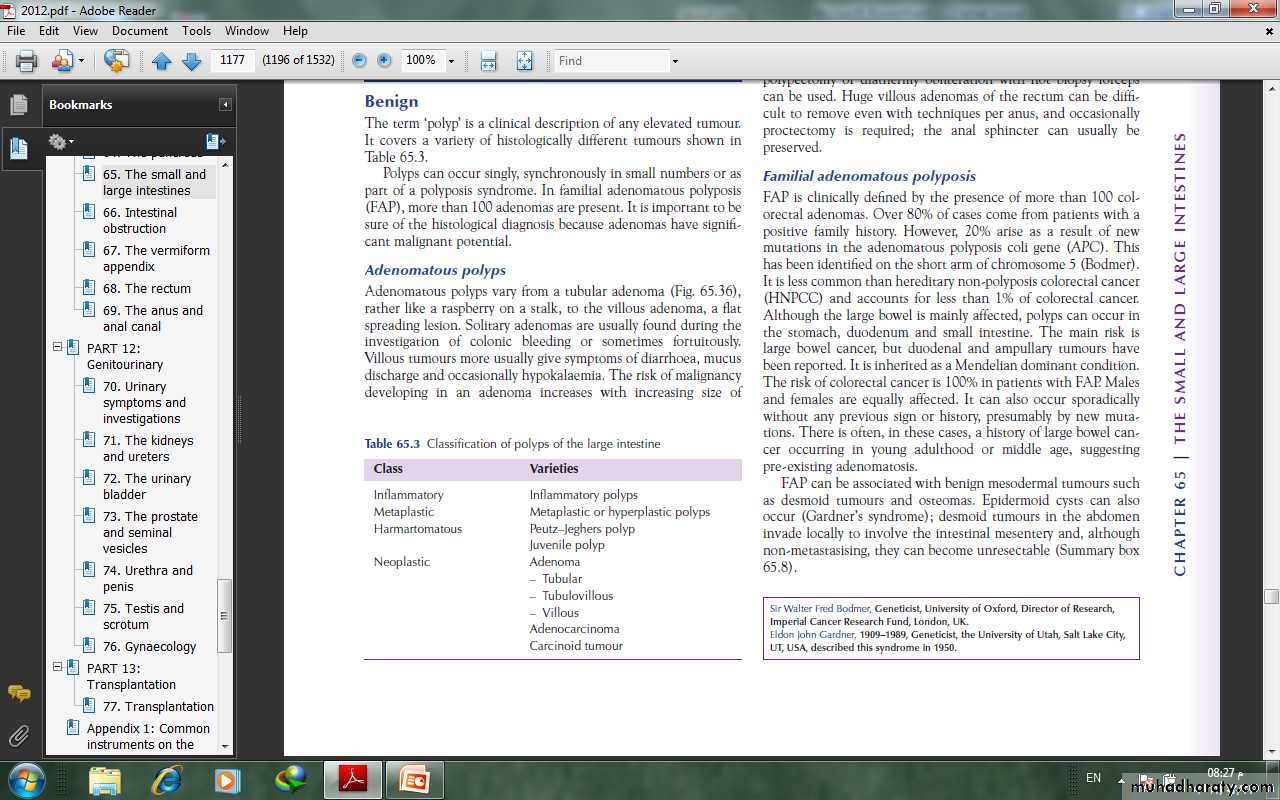

TUMOURS OF THE LARGE INTESTINEBenignThe term ‘polyp’ is a clinical description of any elevated tumour.Polyps can occur singly, synchronously in small numbers or aspart of a polyposis syndrome. In familial adenomatous polyposis(FAP), more than 100 adenomas are present. It is important to besure of the histological diagnosis because adenomas have significant malignant potential.

types of polyps--Adenomatous polypAdenomatous polyps vary from a tubular adenoma ,rather like a raspberry on a stalk, to the villous adenoma, a flatspreading lesion.Villous tumours more usually give symptoms of diarrhoea, mucusdischarge and occasionally hypokalaemia.

The risk of malignancy developing in an adenoma increases with increasing size of tumour; for example, in 1-cm-diameter tubular adenomas there is a 10% risk of cancer, whereas with villous adenomas over 2 cm in diameter, there may be a 15% chance of carcinoma.Adenomas larger than 5 mm in diameter are usually treatedbecause of their malignant potential.

Colonoscopic snare polypectomy or diathermy obliteration with biopsy forceps can be used. Huge villous adenomas of the rectum can be difficult to remove even with techniques per anus, and occasionally proctectomy is required.

Familial adenomatous polyposisFAP is clinically defined by the presence of more than 100 colorectal adenomas. Over 80% of cases come from patients with apositive family history. 20% arise as a result of newmutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene (APC). Thishas been identified on the short arm of chromosome 5

Although the large bowel is mainly affected, polyps can occur inthe stomach, duodenum and small intestine. The main risk islarge bowel cancer, but duodenal and ampullary tumours havebeen reported. It is inherited as a Mendelian dominant condition.The risk of colorectal cancer is 100% in patients with FAP. Malesand females are equally affected.

FAP can be associated with benign mesodermal tumours suchas desmoid tumours and osteomas. Epidermoid cysts can alsooccur (Gardner’s syndrome .desmoid tumours in the abdomeninvade locally to involve the intestinal mesentery and, althoughnon-metastasising, they can become unresectable.

Clinical featuresPolyps are usually visible on sigmoidoscopy by the age of 15 yearsand will almost always be visible by the age of 30 years.Carcinoma of the large bowel occurs 10–20 years after the onsetof the polyposis.

Symptomatic patientsThese are either patients in whom a new mutation has occurredor those from an affected family who have not been screened.They may have loose stools, lower abdominal pain, weight loss,diarrhoea and the passage of blood and mucus

Polyps are seen on sigmoidoscopy and double contrast barium enema. If in doubt, colonoscopy is performed with biopsies to establish the number and histological type of polyps. If over 100 adenomas are present, the diagnosis can be made confidently..

Asymptomatic patientsDirect genetic testing will reveal mutations in 80% of cases. The site of the mutation within the gene has important effectson the phenotype.If there are no adenomas by the age of 30 years, FAP isunlikely. If the diagnosis is made during adolescence, operation isusually deferred to the age of 17 or 18 years or when symptoms ormultiple polyps develop.

Screening policy1 At-risk family members are offered genetic testing in theirearly teens.2 At-risk members of the family should be examined at the ageof 10–12 years, repeated every year.3 Most of those who are going to get polyps will have them at 20years, and these require operation.4 If there are no polyps at 20 years, continue with 5-yearlyexamination until age 50 years; if there are still no polyps,there is probably no inherited gene.

TreatmentColectomy with ileorectal anastomosis has in the past been theusual operation because it avoids an ileostomy in a young patientand the risks of pelvic dissection to nerve function.

The alternative is a restorative proctocolectomy with anileoanal anastomosis. This has a higher complication rate thanileorectal anastomosis. It is indicated in patients with serious rectalinvolvement with polyps.

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch’ssyndrome)This syndrome is characterised by increased risk of colorectalcancer and also cancers of the endometrium, ovary, stomach andsmall intestines. It is an autosomal dominant condition that iscaused by a mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes– MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS and PMS2. The lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is 80%

DiagnosisHNPCC can be diagnosed by genetic testing or Amsterdamcriteria II:• three or more family members with a HNPCC-related cancer,one of whom is a first-degree relative of the other two;• two successive affected generations;• one or more of the HNPCC-related cancers diagnosed beforethe age of 50 years;• exclusion of FAP.

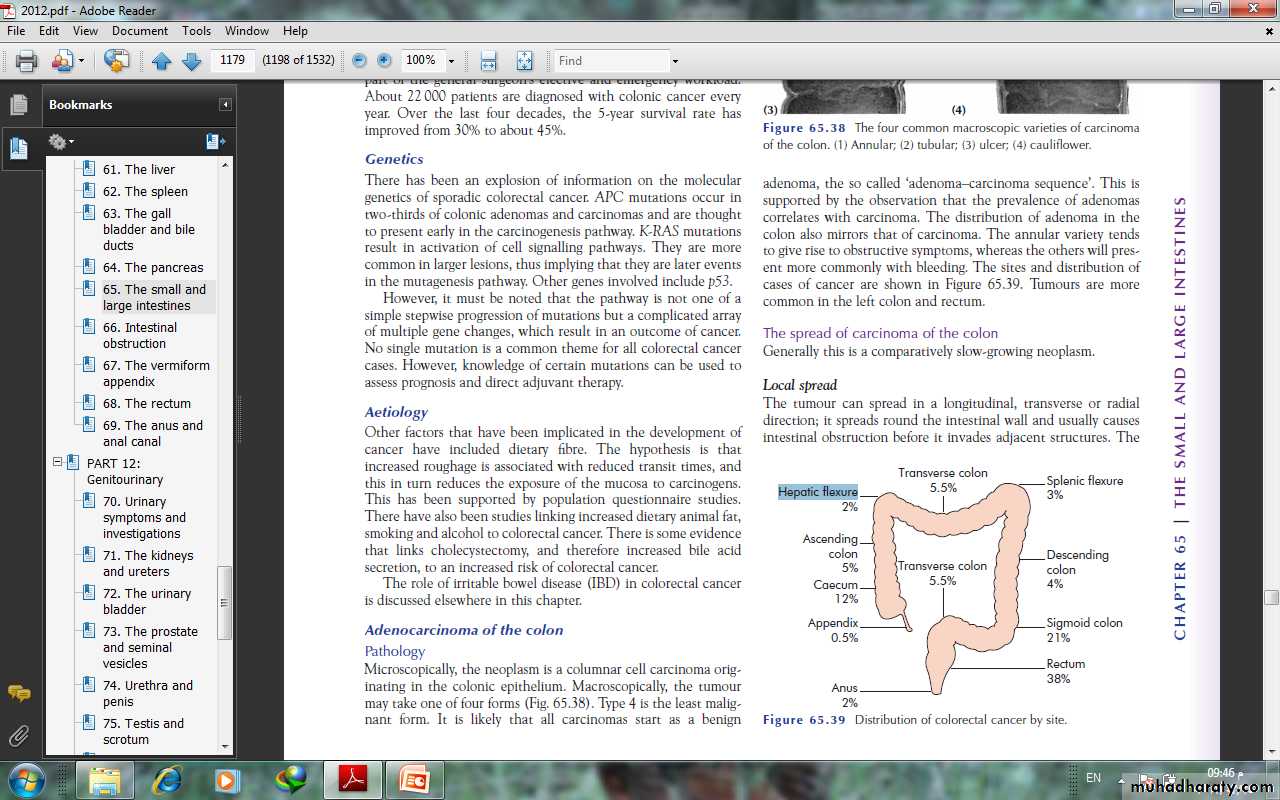

MalignantEpidemiologyAbout 22 000 patients are diagnosed with colonic cancer everyyear. Over the last four decades, the 5-year survival rate hasimproved from 30% to about 45%.

AetiologyOther than genetic factors that have been implicated in the development of cancer have included dietary fibre. The hypothesis is that increased roughage is associated with reduced transit times, and this in turn reduces the exposure of the mucosa to carcinogens. Also increased dietary animal fat, smoking and alcohol to colorectal cancer. There is some evidence that links cholecystectomy, and therefore increased bile acid secretion, to an increased risk of colorectal cancer.

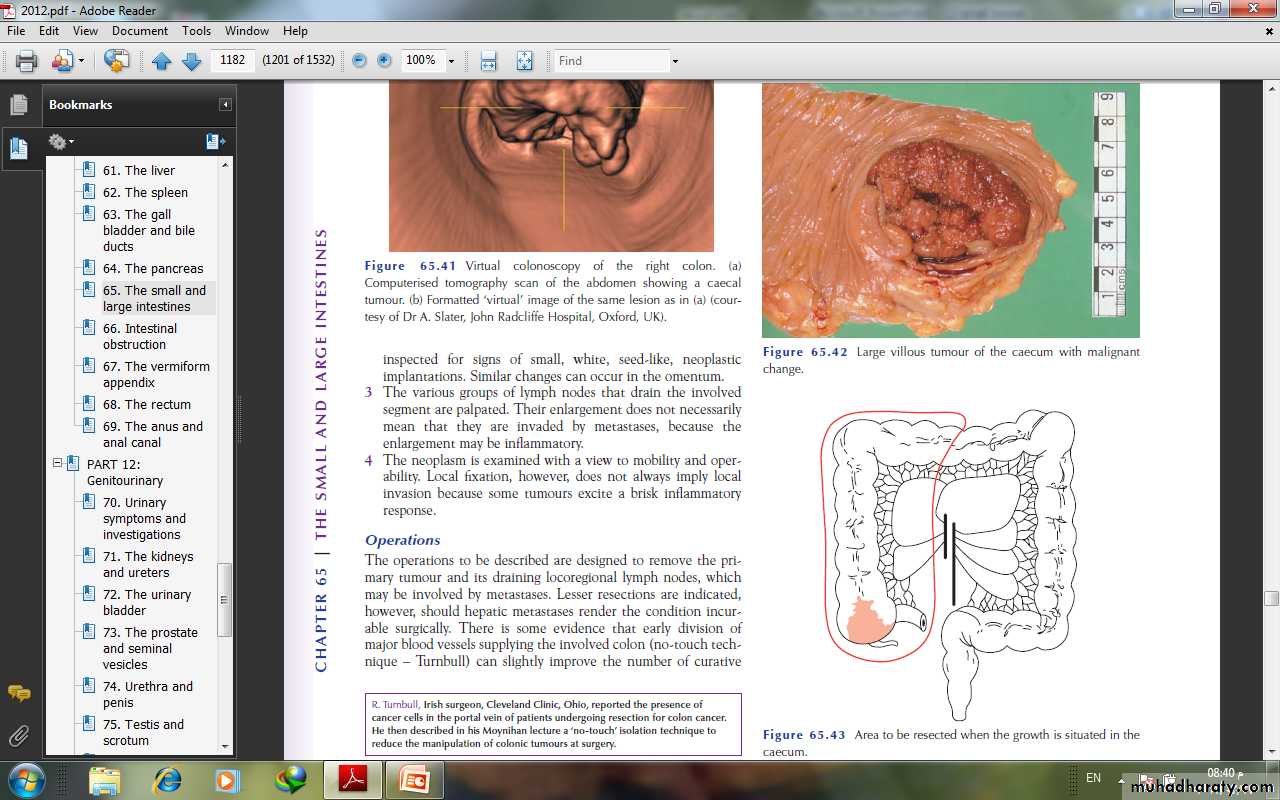

Adenocarcinoma of the colonPathologyMicroscopically, the neoplasm is a columnar cell carcinoma originating in the colonic epithelium. Macroscopically, the tumourmay take one of four forms (1) Annular; (2) tubular; (3) ulcer; (4) cauliflower. Type 4 is the least malignant form. It is likely that all carcinomas start as adenoma, the so called ‘adenoma–carcinoma sequence’.

The annular variety tendsto give rise to obstructive symptoms, whereas the others will present more commonly with bleeding. Tumours are morecommon in the left colon and rectum.

The spread of carcinoma of the colonGenerally this is a comparatively slow-growing neoplasm.Local spreadThe tumour can spread in a longitudinal, transverse or radialdirection; it spreads round the intestinal wall and usually causesintestinal obstruction before it invades adjacent structures.

ulcerative type more commonly invades locally, and an internalfistula may result, for example into the bladder.

Lymphatic spreadLymph nodes draining the colon are grouped as follows:N1: nodes in the immediate vicinity of the bowel wall;N2: nodes arranged along the ileocolic, right colic, midcolic, leftcolic and sigmoid arteries;N3: the apical nodes around the superior and inferior mesentericvessels where they arise from the abdominal aorta.

Bloodstream spreadMetastases are carried to the liver via the portal system, sometimes at an early stage before clinical or operative evidence isdetected (occult hepatic metastases).Transcoelomic spreadRarely, colorectal cancer can spread by way of cells dislodgingfrom the serosa of the bowel to other structures within the peritoneal cavity.

Staging colon cancerThere are several staging systems that are used such as Dukes,tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) . All of them can be usedin order to predict prognosis and standardise treatment, Dukes’ classification for colon cancer is as follows:A: confined to the bowel wall;B: through the bowel wall but not involving the serosa;C: lymph nodes involved.Dukes himself never described a D stage, but this is often used todescribe either advanced local disease or metastases to the liver.

TNM classificationThe TNM classification is more detailed and accurate but moredemanding:• T Tumour stage;• T1 Into submucosa;• T2 Into muscularis propria;• T3 Into pericolic fat but not breaching serosa;• T4 Breaches serosa or directly involving another organ;• N Nodal stage;• N0 No nodes involved;• N1 One or two nodes involved;• N2 Three or more nodes involved;• M Metastases;• M0 No metastases;• M1 Metastases;

Clinical features Carcinoma of the colon usually occurs in patients over 50 years of age, but it is not rare earlier in adult life. Twenty per cent of cases present as an emergency with intestinal obstruction or peritonitis. Those with first-degree relatives who have developed colorectal cancer at the age of 45 years or below are at high risk and may be part of one of the colorectal cancer family syndromes.

Carcinoma of the left side of the colonMost tumours occur in this location. They are usually of thestenosing variety.SymptomsThe main symptoms are those of increasing intestinal obstruction.This includes lower abdominal pain, which may be colickyin nature, and abdominal distension. The patient may have achange in bowel habit with alternating diarrhoea and constipation

Carcinoma of the sigmoidIn addition to symptoms of intestinal obstruction, a low tumourmay give rise to a feeling of the need for evacuation, which mayresult in tenesmus accompanied by the passage of mucus andblood. Bladder symptoms are not unusual and, in some instances,may herald a colovesical fistula.Carcinoma of the transverse colonThis may be mistaken for a carcinoma of the stomach because ofthe position of the tumour together with anaemia and lassitude.

Carcinoma of the caecum and ascending colonThis may present with the following:• anaemia, severe and unrespond to treatment;• the presence of a mass in the right iliac fossa• a carcinoma of the caecum can be the apex of an intussusceptionpresenting with the symptoms of intermittent obstruction.

Metastatic diseasePatients may present for the first time with liver metastases andan enlarged liver, ascites from carcinomatosis peritonei and, morerarely, metastases to the lung, skin, bone and brain.

Methods of investigation of colon cancerFlexible sigmoidoscopyThe 60-cm, fibreoptic, flexible sigmoidoscope is increasinglybeing used in the out-patient clinic or in special rectal bleedingclinics. The patient is prepared with a disposable enema andsedation is not usually necessary. This is particularly useful in supplementing barium investigations where diagnosis is difficult due to diverticular disease.

ColonoscopyThis is now the investigation of choice if colorectal cancer is suspected provided the patient is fit enough to undergo the bowelpreparation. It has the advantage of not only picking up a primarycancer but also having the ability to detect synchronous polyps oreven multiple carcinomas, which occur in 5% of cases. Ideally,every case should be proven histologically before surgery. Fullbowel preparation and sedation are necessary. However, one mustbe aware of a small risk of perforation.

RadiologyDouble-contrast barium enema is used when colonoscopy is contraindicated.it shows a cancer of the colon as a constant irregular filling defect.Ultrasonography is often used as a screening investigation forliver metastases over the size of 1.5 cm, and CT is used in patientswith large palpable abdominal masses, to determine local invasion,and is particularly used in the pelvis in the assessment ofrectal cancer.

Apple core appearance

there has been the introduction of virtual colonoscopy, which is effective in picking up polyps down to size of 6 mm. This mayeven replace colonoscopy as the standard investigation in thefuture. Urograms have a role in left-sided tumours where there is evidence of hydronephrosis on CT or ultrasound.

TreatmentPreoperative preparationRecent literature has suggested that no bowel preparation is safefor right-sided colonic surgery. The most commonly used methodis dietary restriction to fluids only for 48 hours before surgery; onthe day before the operation, two sachets of Picolax are taken to purge the colon. In addition, a rectal washout may be necessary. A stoma site is carefully discussed with the stoma care nursing specialist and anti-embolus stockings are fitted; the patient is started on prophylactic subcutaneous heparin, and intravenous prophylactic antibiotics are given at the start of surgery.

When intestinal obstruction is present, preparation in this waymay precipitate abdominal pain, and it may be safer to use an ontable lavage technique at the time of the operation

The test of operabilityThe abdomen is opened and the tumour assessed for resectability.1 The liver is palpated for secondary deposits, the presence ofwhich is not necessarily a contraindication to resection.2 The peritoneum, particularly the pelvic peritoneum, isinspected for signs of small, white, seed-like, neoplasticimplantations.3 The various groups of lymph nodes that drain the involvedsegment are palpated.4 The neoplasm is examined with a view to mobility and operability.

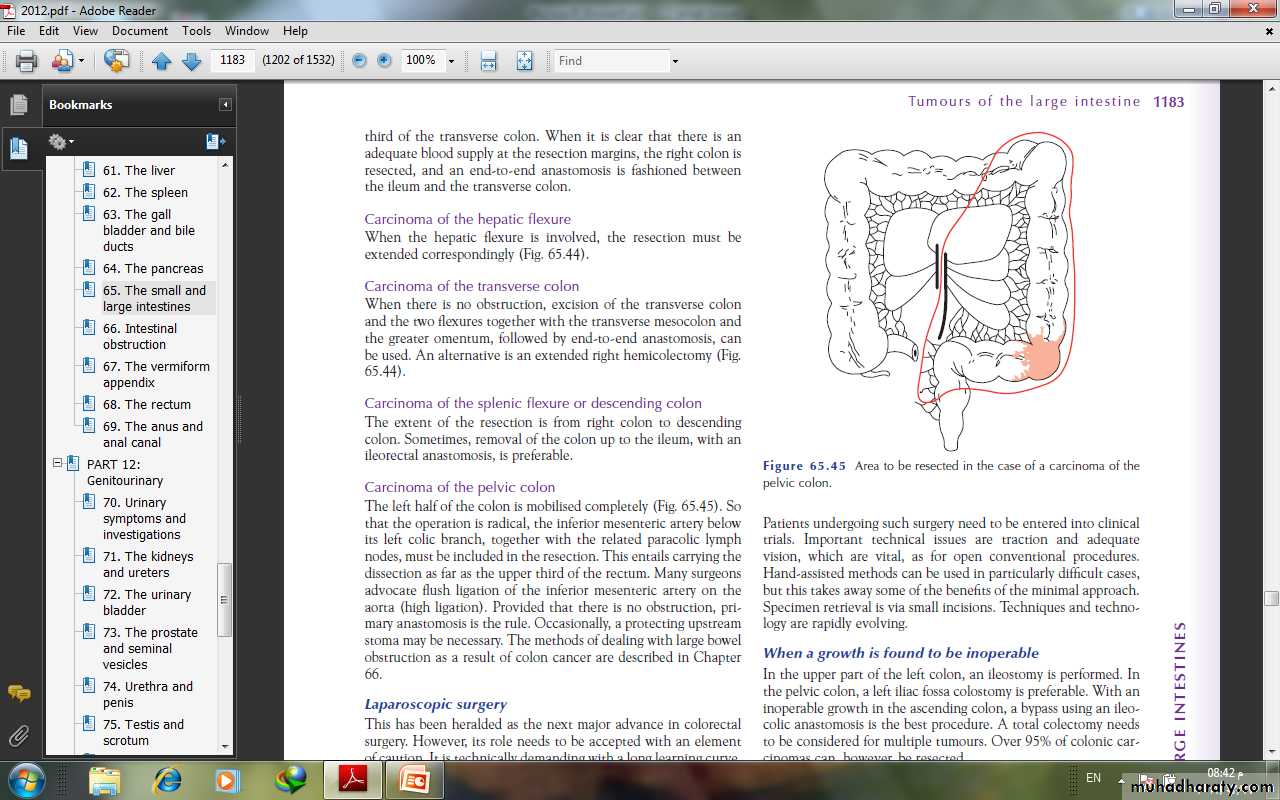

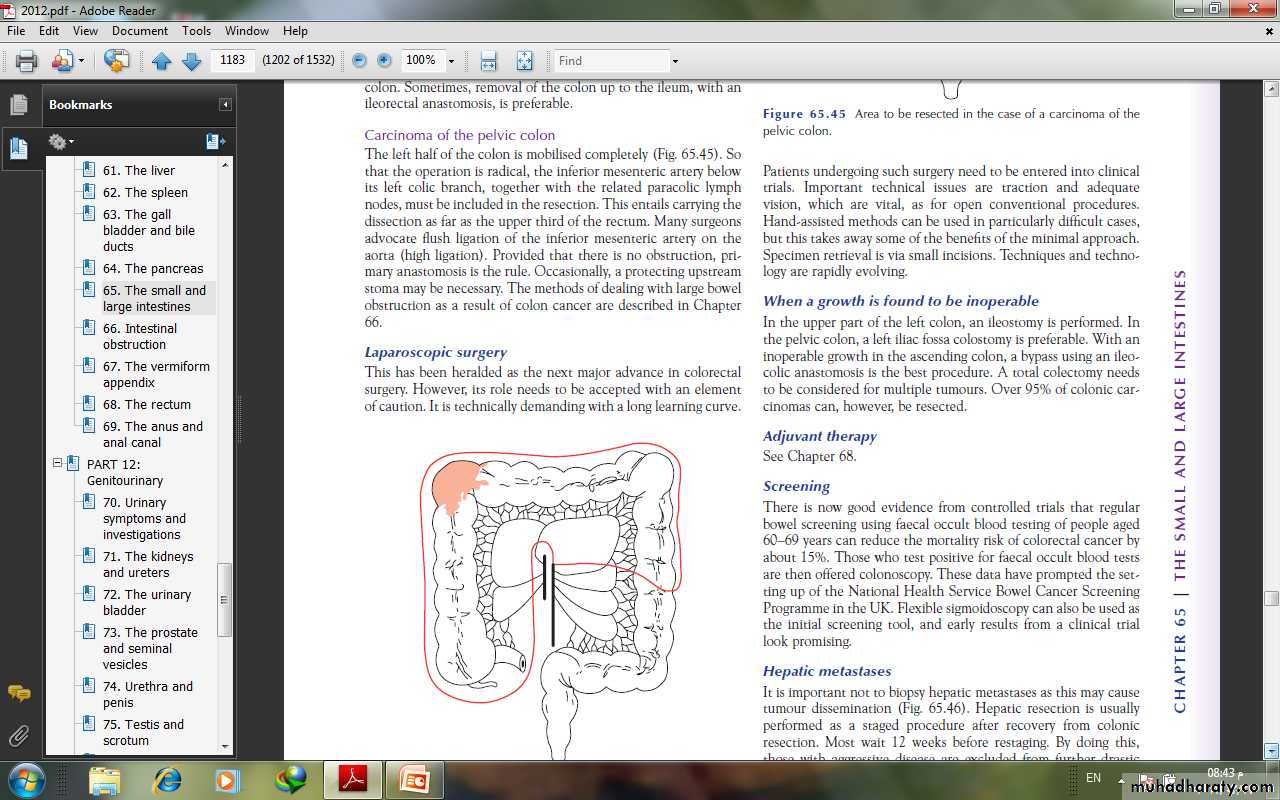

OperationsThe operations to be described are designed to remove the primary tumour and its draining locoregional lymph nodes, whichmay be involved by metastases. Lesser resections are indicated,however, should hepatic metastases render the condition incurable surgically. There is some evidence that early division ofmajor blood vessels supplying the involved colon (no-touch technique.

When a growth is found to be inoperableIn the upper part of the left colon, an ileostomy is performed. Inthe pelvic colon, a left iliac fossa colostomy is preferable. With aninoperable growth in the ascending colon, a bypass using an ileocolic anastomosis is the best procedure.

ScreeningThe regular bowel screening using faecal occult blood testing of people aged 60–69 years can reduce the mortality risk of colorectal cancer by about 15%. Those who test positive for faecal occult blood tests are then offered colonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy can also be used as the initial screening .

OTHER DISORDERSTraumatic ruptureThe intestine can be ruptured with or without an external wound– so called blunt trauma . The most common cause ofthis is a blow to the abdomen that crushes the bowel against thevertebral column or sacrum; also, a rupture is more likely to occurwhere part of the gut has been fixed, for example in a hernia, orwhere a fixed part of the gut joins a mobile part such as the duodenojejunal flexure.

In small perforations, the mucosa may prolapse through thehole and partly seal it, making the early signs misleading. In addition, there may be a laceration in the mesentery. The patient will then have a combination of intra-abdominal bleeding and release of intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, giving rise to peritonitis.

Traumatic rupture of the large intestine is much less common.In blast injuries of the abdomen following the detonation of a bomb, the pelvic colon is particularly at risk of rupture. Compressed air rupture can follow the dangerous practical joke of turning on an airline carrying compressed air near the victim’s anus.

STOMASColostomyA colostomy is an artificial opening made in the large bowel todivert faeces and flatus to the exterior, where it can be collectedin an external appliance. Depending on the purpose for which thediversion has been necessary, a colostomy may be temporary orpermanent.

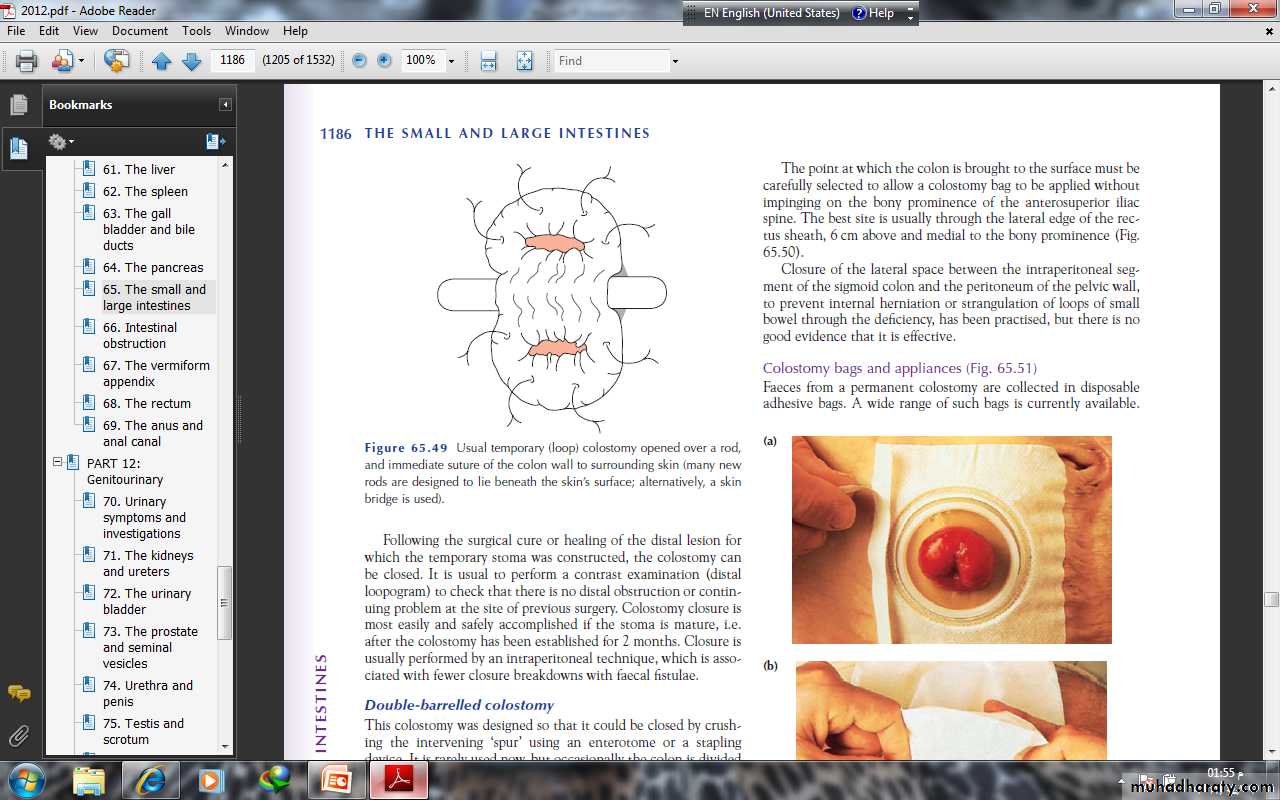

Temporary colostomyA transverse loop colostomy has in the past been most commonlyused to defunction an anastomosis after an anterior resection. Itis now less commonly employed as it is fraught with complicationsand is difficult to manage; a loop ileostomy is preferred.A loop left iliac fossa colostomy is still sometimes used to preventfaecal peritonitis developing following traumatic injury tothe rectum, to facilitate the operative treatment of a high fistulain-ano and incontinence.

A temporary loop colostomy is made, bringing a loop of colonto the surface, where it is held in place by a plastic bridge passedthrough the mesentery. Once the abdomen has been closed, thecolostomy is opened. When firm adhesion of the colostomy to the abdominal wall has taken place, the bridge can be removed after 7 days. Colostomy closure is most easily and safely accomplished if the stoma is mature, i.e. after the colostomy has been established for 2 months.

Permanent colostomyThis is usually formed after excision of the rectum for a carcinomaby the abdominoperineal technique. it is formed by bringing the distal end (end-colostomy) of the divided colon to the surface in the left iliac fossa .

The point at which the colon is brought to the surface must becarefully selected to allow a colostomy bag to be applied withoutimpinging on the bony prominence of the anterosuperior iliacspine. The best site is usually through the lateral edge of the rectussheath, 6 cm above and medial to the bony prominence.

Colostomy bags and appliances Faeces from a permanent colostomy are collected in disposableadhesive bags. A wide range of such bags is currently available. Many now incorporate a stomahesive backing, which can be leftin place for several days. In most hospitals, a stoma care service isavailable to offer advice to patients, to acquaint them with thelatest appliances and to provide the appropriate psychologicaland practical help.

Complications of colostomiesThe following complications can occur to any colostomy but aremore common after poor technique or siting of the stoma:• prolapse;• retraction;• necrosis of the distal end;• fistula formation;• stenosis of the orifice;• colostomy hernia;• bleeding (usually from granulomas around the margin of thecolostomy);• colostomy ‘diarrhoea’: this is usually an infective enteritis andwill respond to oral metronidazole 200 mg three times daily.

Intestinalobstruction

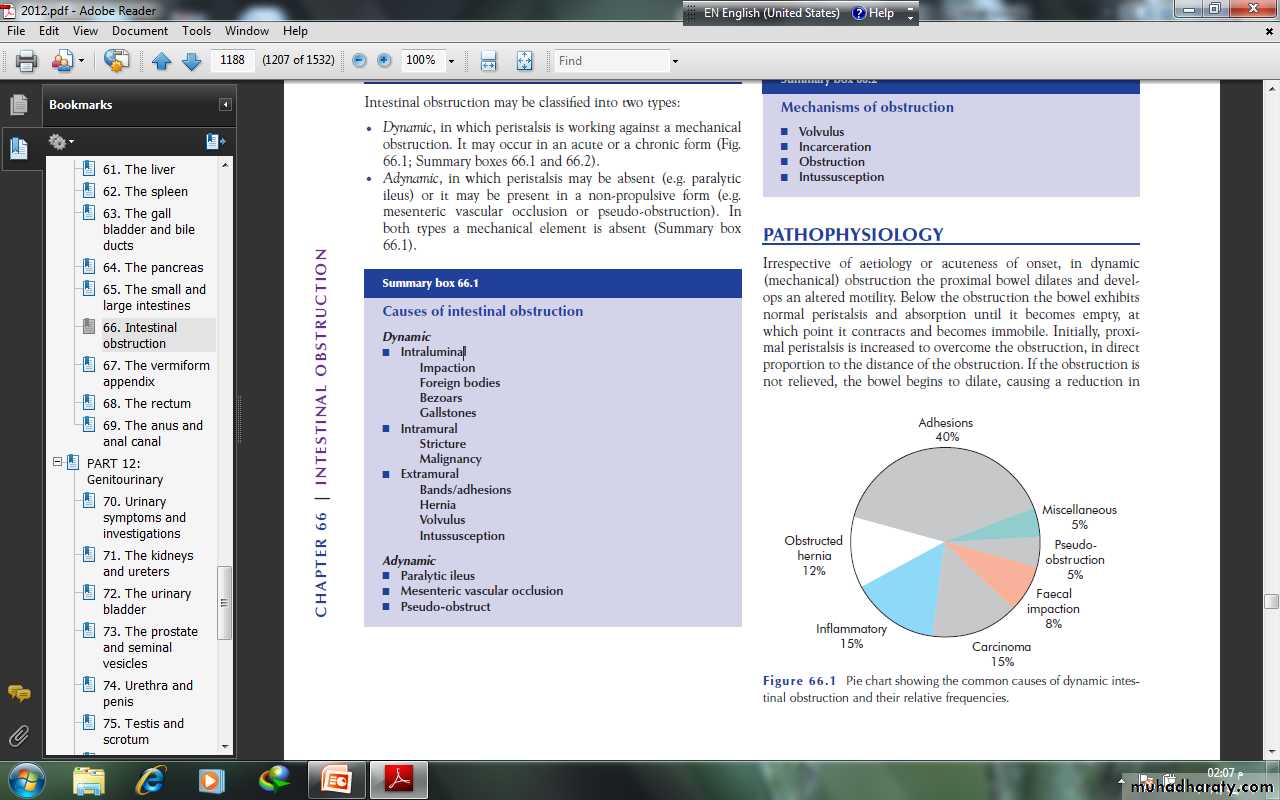

CLASSIFICATIONIntestinal obstruction may be classified into two types:• Dynamic, in which peristalsis is working against a mechanicalobstruction. It may occur in an acute or a chronic form.• Adynamic, in which peristalsis may be absent (e.g. paralyticileus) or it may be present in a non-propulsive form (e.g.mesenteric vascular occlusion or pseudo-obstruction). Inboth types a mechanical element is absent.PATHOPHYSIOLOGY In dynamic (mechanical) obstruction the proximal bowel dilates and develops an altered motility. Below the obstruction the bowel exhibits normal peristalsis and absorption until it becomes empty, at which point it contracts and becomes immobile. Initially, proximal peristalsis is increased to overcome the obstruction, in direct proportion to the distance of the obstruction. If the obstruction is not relieved, the bowel begins to dilate, causing a reduction inperistaltic strength, ultimately resulting in flaccidity and paralysis.This is a protective phenomenon to prevent vascular damage secondary to increased intraluminal pressure.

The distension proximal to an obstruction is produced by twofactors:• Gas: there is a significant overgrowth of both aerobic andanaerobic organisms, resulting in considerable gas production.Following the reabsorption of oxygen and carbon dioxide, themajority is made up of nitrogen (90%) and hydrogen sulphide.• Fluid: this is made up of the various digestive juices. Followingobstruction, fluid accumulates within the bowel wall and anyexcess is secreted into the lumen, whilst absorption from thegut is retarded. Dehydration and electrolyte loss are thereforedue to:– reduced oral intake;– defective intestinal absorption;– losses as a result of vomiting;– sequestration in the bowel lumen.

STRANGULATIONWhen strangulation occurs, the viability of the bowel is threatenedsecondary to a compromised blood supply

STRANGULATIONWhen strangulation occurs, the viability of the bowel is threatenedsecondary to a compromised blood supply The venous return is compromised before the arterial supply. Theresultant increase in capillary pressure leads to local mural distensionwith loss of intravascular fluid and red blood cells intramurallyand extraluminally. Once the arterial supply is impaired,haemorrhagic infarction occurs.

As the viability of the bowel iscompromised there is marked translocation and systemic exposureto anaerobic organisms with their associated toxins. Themorbidity of intraperitoneal strangulation is far greater than withan external hernia, which has a smaller absorptive surface.

The morbidity and mortality associated with strangulation aredependent on age and extent. In strangulated external hernias thesegment involved is short and the resultant blood and fluid loss issmall. When bowel involvement is extensive the loss of blood andcirculatory volume will cause peripheral circulatory failure.

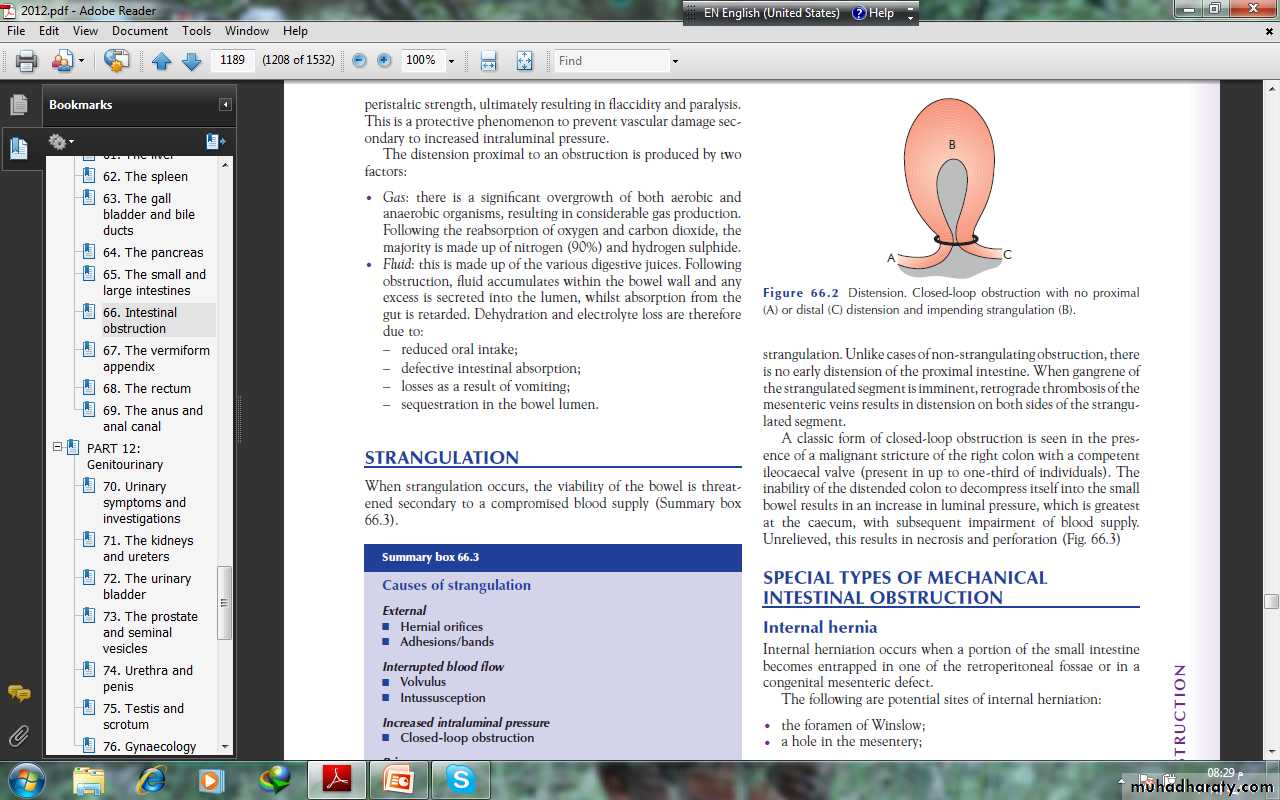

Closed-loop obstructionThis occurs when the bowel is obstructed at both the proximal anddistal points . It is present in many cases of intestinalstrangulation. Unlike cases of non-strangulating obstruction, thereis no early distension of the proximal intestine. When gangrene ofthe strangulated segment is imminent, retrograde thrombosis of the mesenteric veins results in distension on both sides of the strangulated segment.

A classic form of closed-loop obstruction is seen in the presenceof a malignant stricture of the right colon with a competentileocaecal valve (present in up to one-third of individuals)

The inability of the distended colon to decompress itself into the small bowel results in an increase in luminal pressure, which is greatest at the caecum, with subsequent impairment of blood supply. Unrelieved, this results in necrosis and perforation

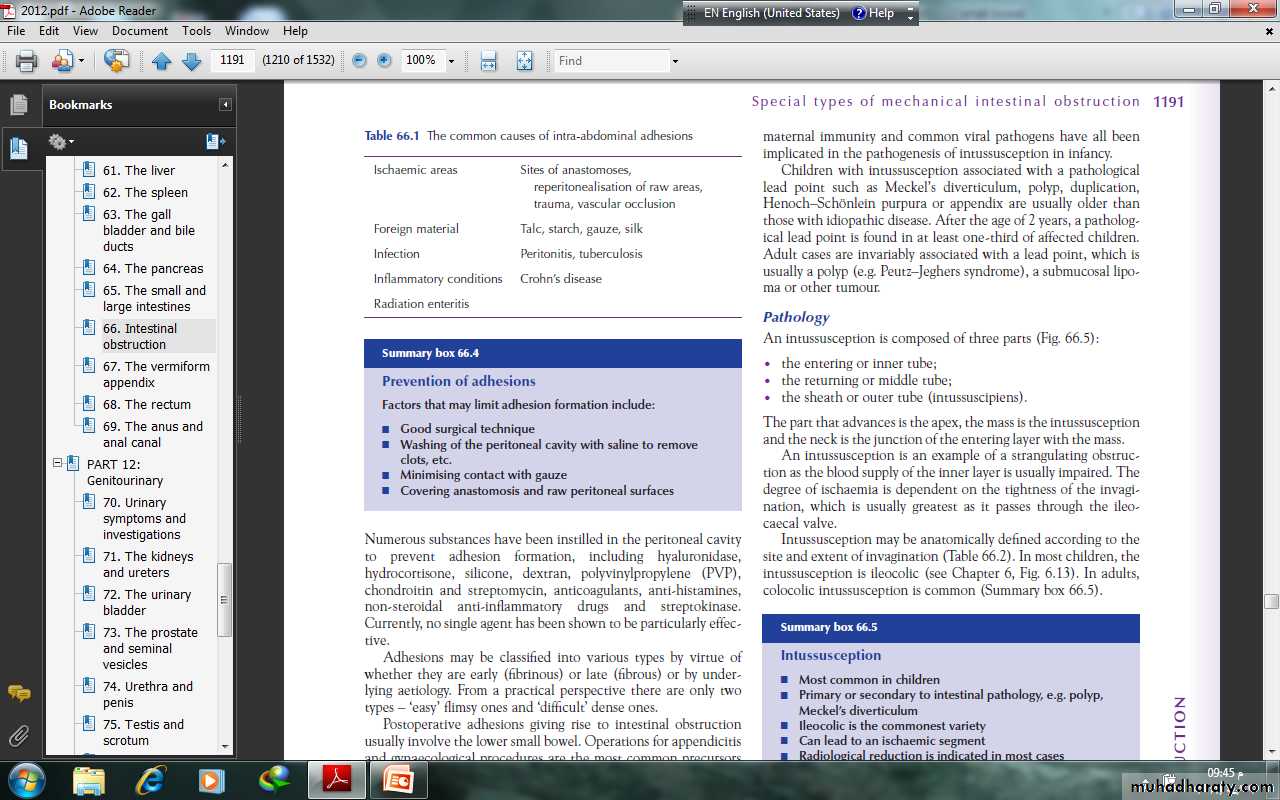

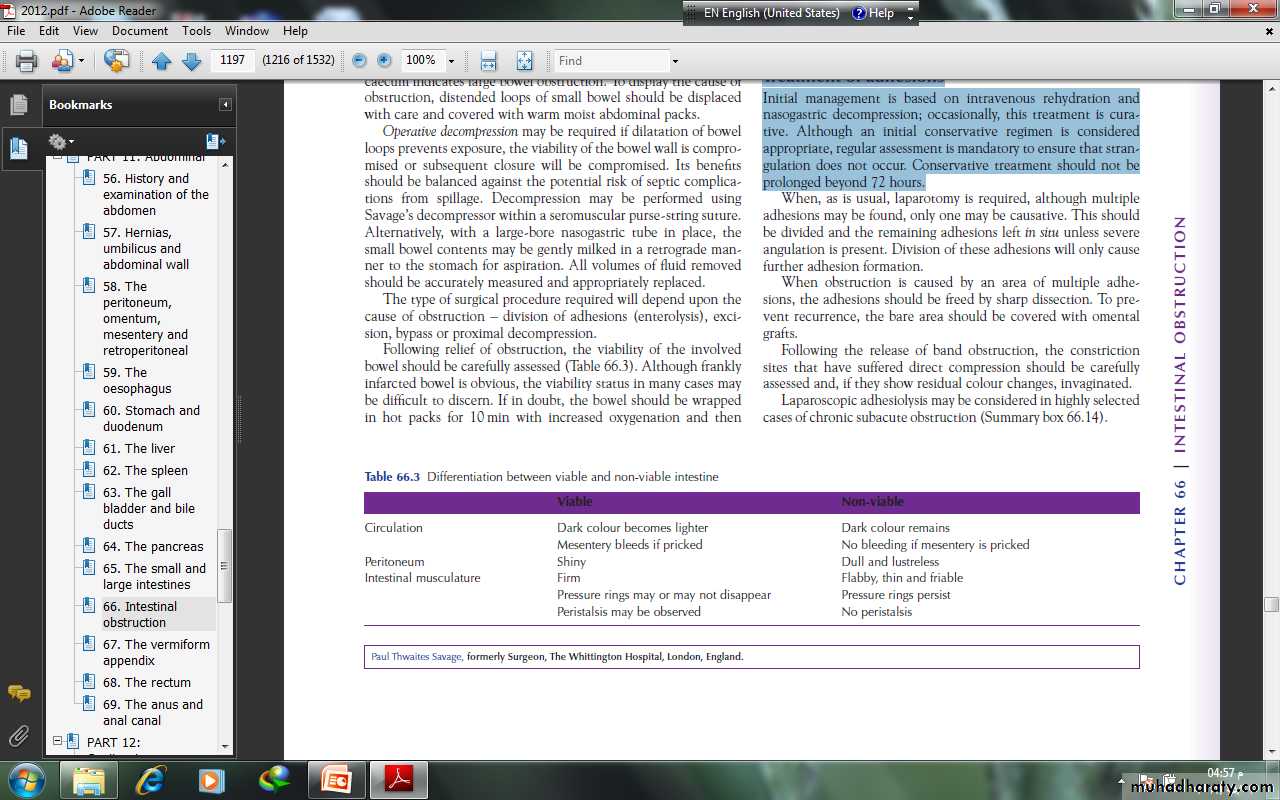

SPECIAL TYPES OF MECHANICALINTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION Obstruction by adhesions and bandsAdhesionsIn western countries where abdominal operations are common,adhesions and bands are the most common cause of intestinalobstruction. Furthermore, in the early postoperative period, theonset of such a mechanical obstruction may be difficult to differentiate from paralytic ileus.

Any source of peritoneal irritation results in local fibrin production,which produces adhesions between apposed surfaces.Early fibrinous adhesions may disappear when the cause isremoved or they may become vascularised and be replaced bymature fibrous tissue.

There are several factors that may limit adhesion formation

Numerous substances have been instilled in the peritoneal cavityto prevent adhesion formation, including hyaluronidase,hydrocortisone, silicone, dextran, polyvinylpropylene (PVP), anticoagulants, anti-histamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Postoperative adhesions giving rise to intestinal obstructionusually involve the lower small bowel. Operations for appendicitisand gynaecological procedures are the most common precursorsand are an indication for early intervention

Bands This may be:• congenital, e.g. obliterated vitellointestinal duct;• a string band following previous bacterial peritonitis;• a portion of greater omentum, usually adherent to theparietes.

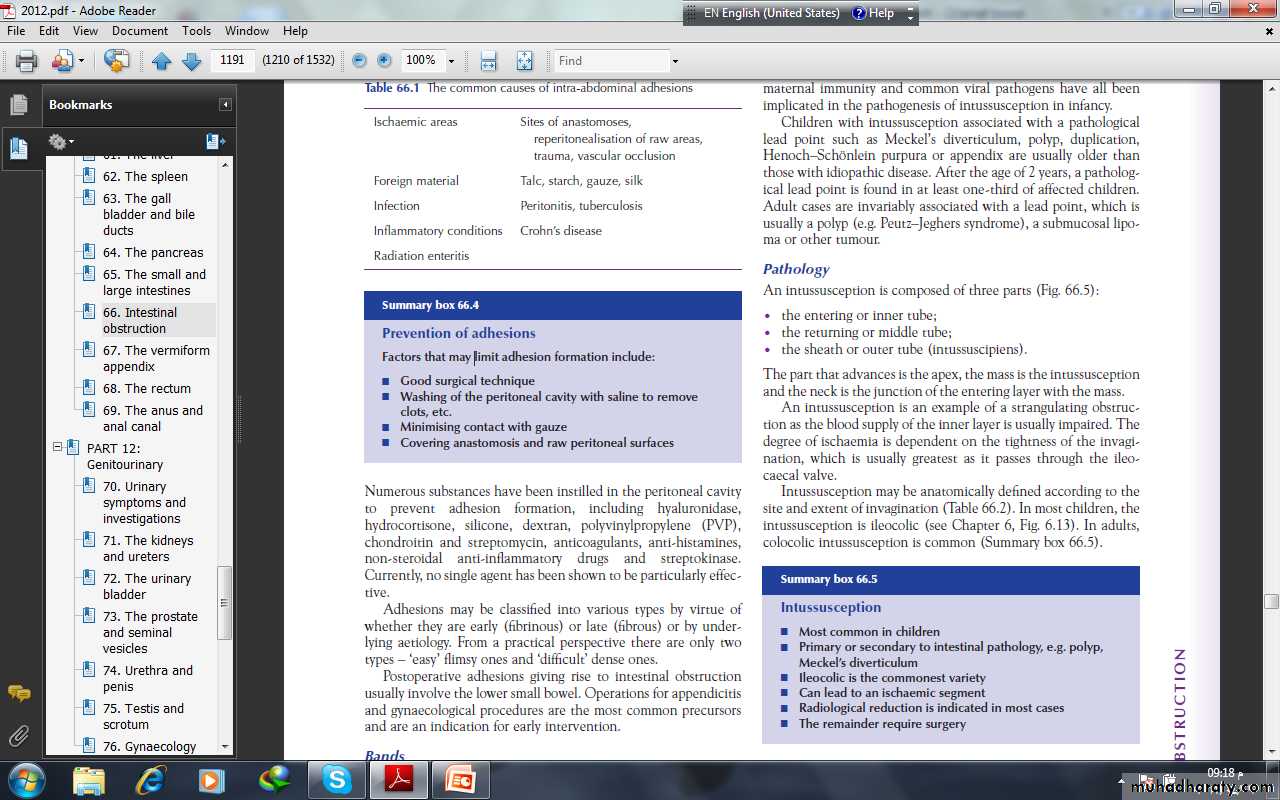

Acute intussusceptionThis occurs when one portion of the gut becomes invaginatedwithin an immediately adjacent segment; almost invariably, it isthe proximal into the distal.The condition is encountered most commonly in children,with a peak incidence between 5 and 10 months of age. About90% of cases are idiopathic but an associated upper respiratorytract infection or gastroenteritis may precede the condition. It isbelieved that hyperplasia of Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileummay be the initiating event. Weaning, loss of passively acquired maternal immunity and common viral pathogens have all beenimplicated in the pathogenesis of intussusception in infancy.

Children with intussusception associated with a pathologicallead point such as Meckel’s diverticulum, polyp, duplication,Henoch–Schِnlein purpura or appendix are usually older thanthose with idiopathic disease. After the age of 2 years, a pathological lead point is found in at least one-third of affected children.Adult cases are invariably associated with a lead point, which isusually a polyp (e.g. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), a submucosal lipoma or other tumour.

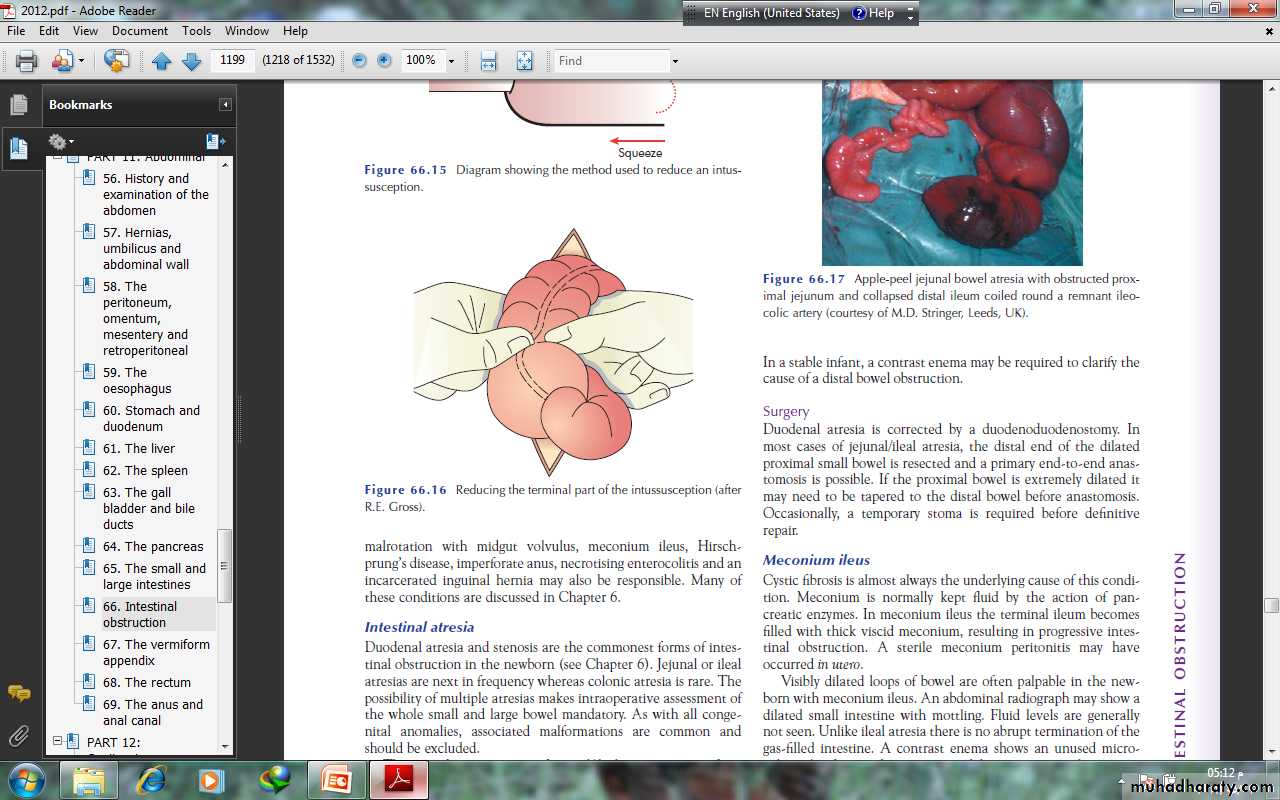

PathologyAn intussusception is composed of three parts :• the entering or inner tube;• the returning or middle tube;• the sheath or outer tube (intussuscipiens).The part that advances is the apex, the mass is the intussusceptionand the neck is the junction of the entering layer with the mass.An intussusception is an example of a strangulating obstructionas the blood supply of the inner layer is usually impaired. Thedegree of ischaemia is dependent on the tightness of the invagination,which is usually greatest as it passes through the ileocaecalvalve.Intussusception may be anatomically defined according to thesite and extent of invagination . In most children, theintussusception is ileocolic . colocolic intussusception is common

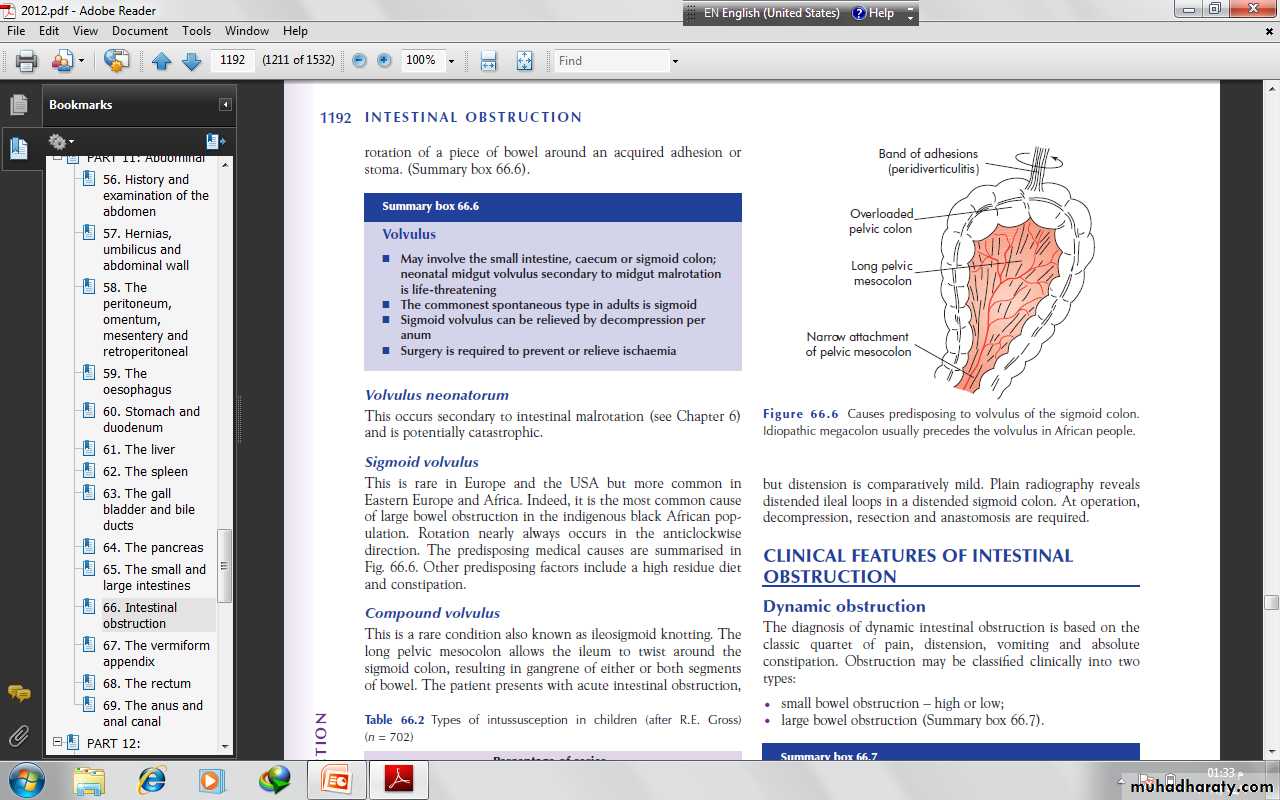

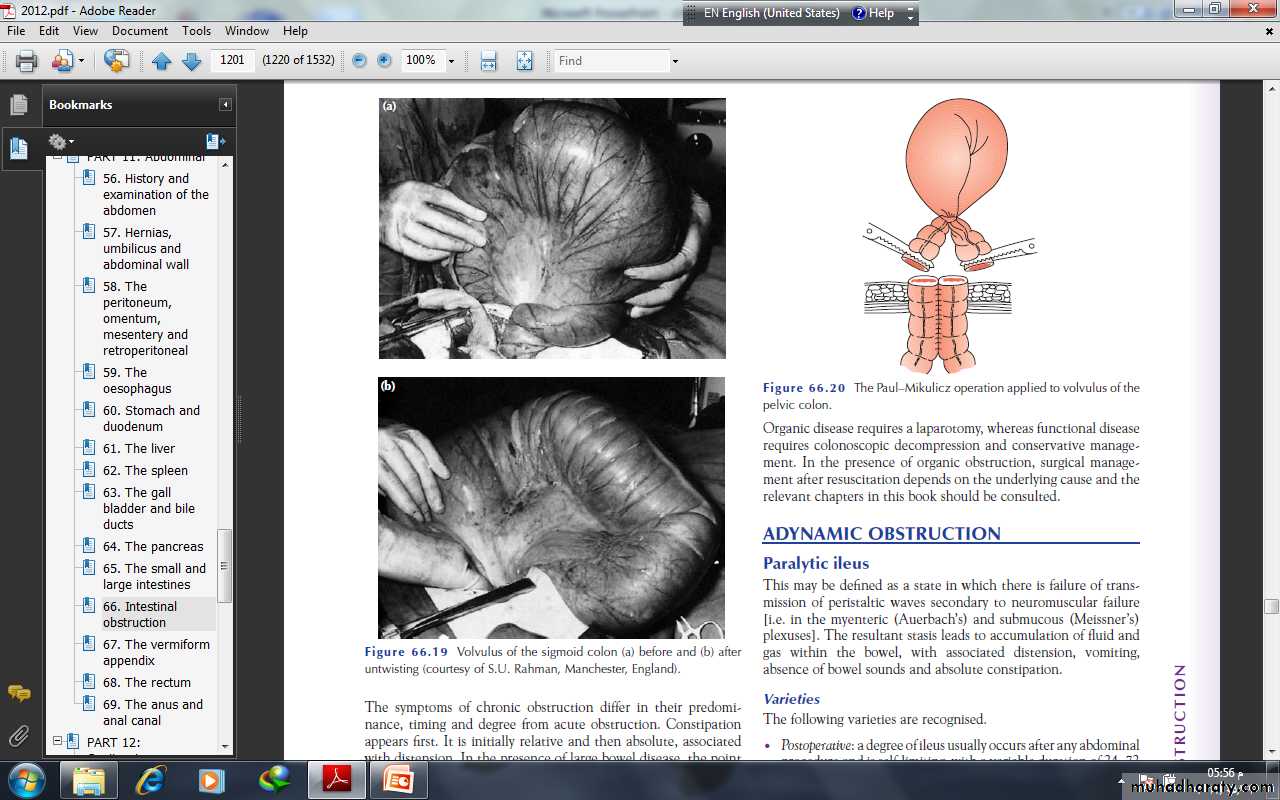

VolvulusA volvulus is a twisting or axial rotation of a portion of bowelabout its mesentery. When complete it forms a closed loop ofobstruction with resultant ischaemia secondary to vascular occlusion.Volvuli may be primary or secondary. The primary form occurssecondary to congenital malrotation of the gut, abnormal mesenteric attachments or congenital bands. Examples include volvulus neonatorum, caecal volvulus and sigmoid volvulus. Asecondary volvulus, which is the more common variety, is due to rotation of a piece of bowel around an acquired adhesion orstoma.

Sigmoid volvulusThis is rare in Europe and the USA but more common inEastern Europe and Africa. Indeed, it is the most common causeof large bowel obstruction in the indigenous black African population. Rotation nearly always occurs in the anticlockwisedirection.

Internal herniaInternal herniation occurs when a portion of the small intestinebecomes entrapped in one of the retroperitoneal fossae or in acongenital mesenteric defect.The following are potential sites of internal herniation:• the foramen of Winslow;• a hole in the mesentery;

• a hole in the transverse mesocolon;• defects in the broad ligament;• congenital or acquired diaphragmatic hernia;• duodenal retroperitoneal fossae • caecal/appendiceal retroperitoneal fossae • intersigmoid fossa. Internal herniation in the absence of adhesions is uncommonand a preoperative diagnosis is unusual

Obstruction from enteric stricturesSmall bowel strictures usually occur secondary to tuberculosis orCrohn’s disease. Malignant strictures associated with lymphomaare common, whereas carcinoma and sarcoma are rare

Bolus obstructionBolus obstruction in the small bowel may be caused by food, gallstones, trichobezoar, phytobezoar, stercoliths and worms

GallstonesThis type of obstruction tends to occur in the elderly secondaryto erosion of a large gallstone through the gall bladder into theduodenum. Classically, there is impaction about 60 cm proximalto the ileocaecal valve. The patient may have recurrent attacksas the obstruction is frequently incomplete . At laparotomy it may be possibleto crush the stone within the bowel lumen, after milking itproximally. If not, the intestine is opened and the gallstoneremoved.

FoodBolus obstruction may occur after partial or total gastrectomywhen unchewed articles can pass directly into the small bowel.Fruit and vegetables are particularly liable to cause obstruction.

Trychobezoars and phytobezoarsThese are firm masses of undigested hair balls and fruit/vegetablefibre . The former is due to persistent hair chewing orsucking, and may be associated with an underlying psychiatricabnormality. Predisposition to phytobezoars results from a highfibre intake, inadequate chewing, previous gastric surgery,hypochlorhydria and loss of the gastric pump mechanism.

WormsAscaris lumbricoides may cause low small bowel obstruction,particularly in children, the institutionalised and those near thetropics.

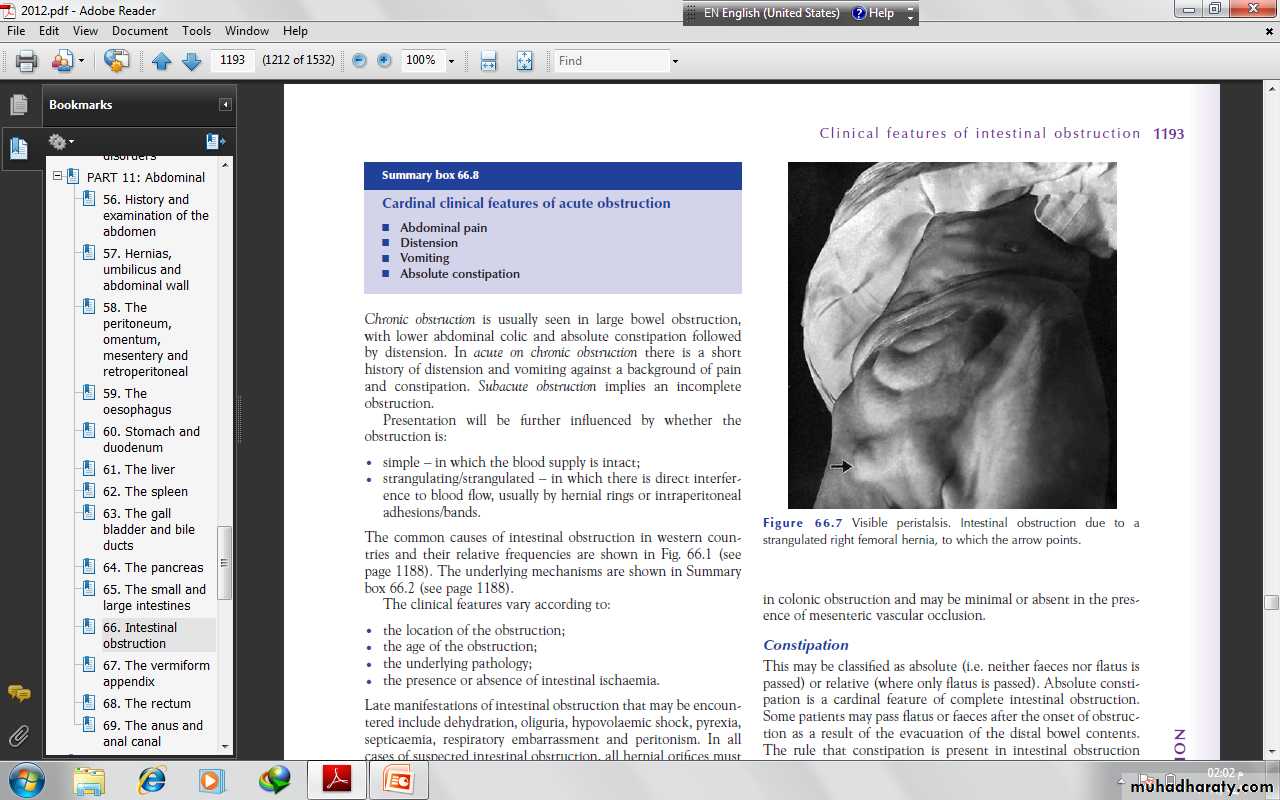

CLINICAL FEATURES OF INTESTINALOBSTRUCTIONDynamic obstructionThe diagnosis of dynamic intestinal obstruction is based on theclassic quartet of pain, distension, vomiting and absoluteconstipation. Obstruction may be classified clinically into twotypes:• small bowel obstruction – high or low;• large bowel obstruction

The nature of the presentation will also be influenced by whetherthe obstruction is:• acute;• chronic;• acute on chronic;• subacute.Acute obstruction usually occurs in small bowel obstruction, withsudden onset of severe colicky central abdominal pain, distensionand early vomiting and constipation