Medicine

Notes…

1

Presenting problems in disorders of sodium balance and water balance

DISORDERS OF WATER BALANCE:

Daily water intake can vary from about 500 mL to several litres a day. While a certain

amount of water is lost through the stool,

sweat and the respiratory tract (‘insensible

losses’, approximately 800 mL/day), and some water is generated by oxidative

metabolism

(‘metabolic water’, approximately 400 mL/day), the kidneys are chiefly

responsible for adjusting water excretion to maintain constancy of body water content and

body fluid osmolality (reference range 280

–295 milliosmol/kg).

Presenting problems in disorders of water balance:

Disturbances in body water balance, in the absence of changes in sodium balance, alter

plasma sodium concentration and hence plasma osmolality. When extracellular

osmolality changes abruptly, water flows rapidly across cell membranes with resultant cell

swelling (during hypo-osmolality) or shrinkage (during hyperosmolality).

Cerebral function is very sensitive to such volume changes, particularly brain swelling

during hypo-osmolality, which can lead to an increase in intracerebral pressure and

reduced cerebral perfusion.

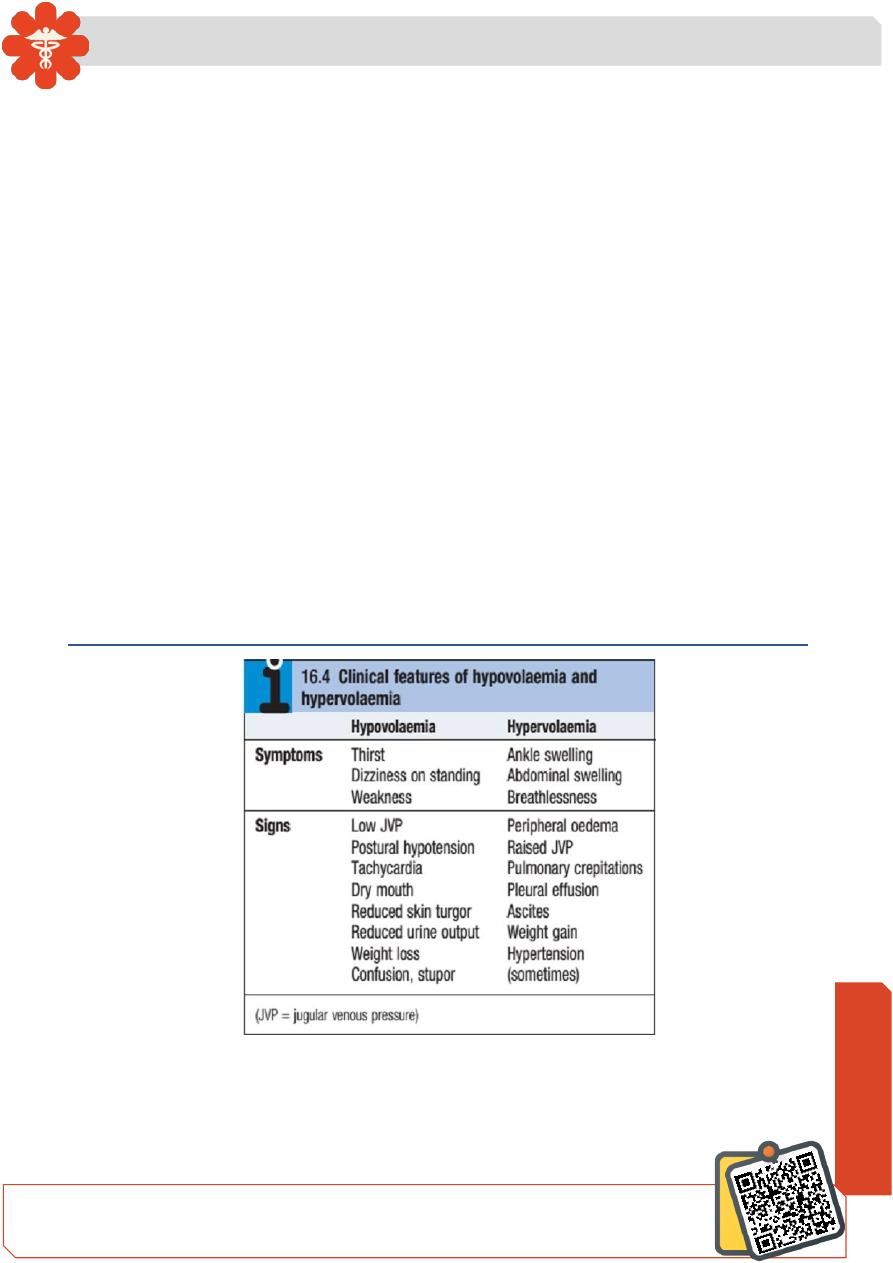

The diagnosis of hypovolaemia is based on characteristic symptoms and signs.

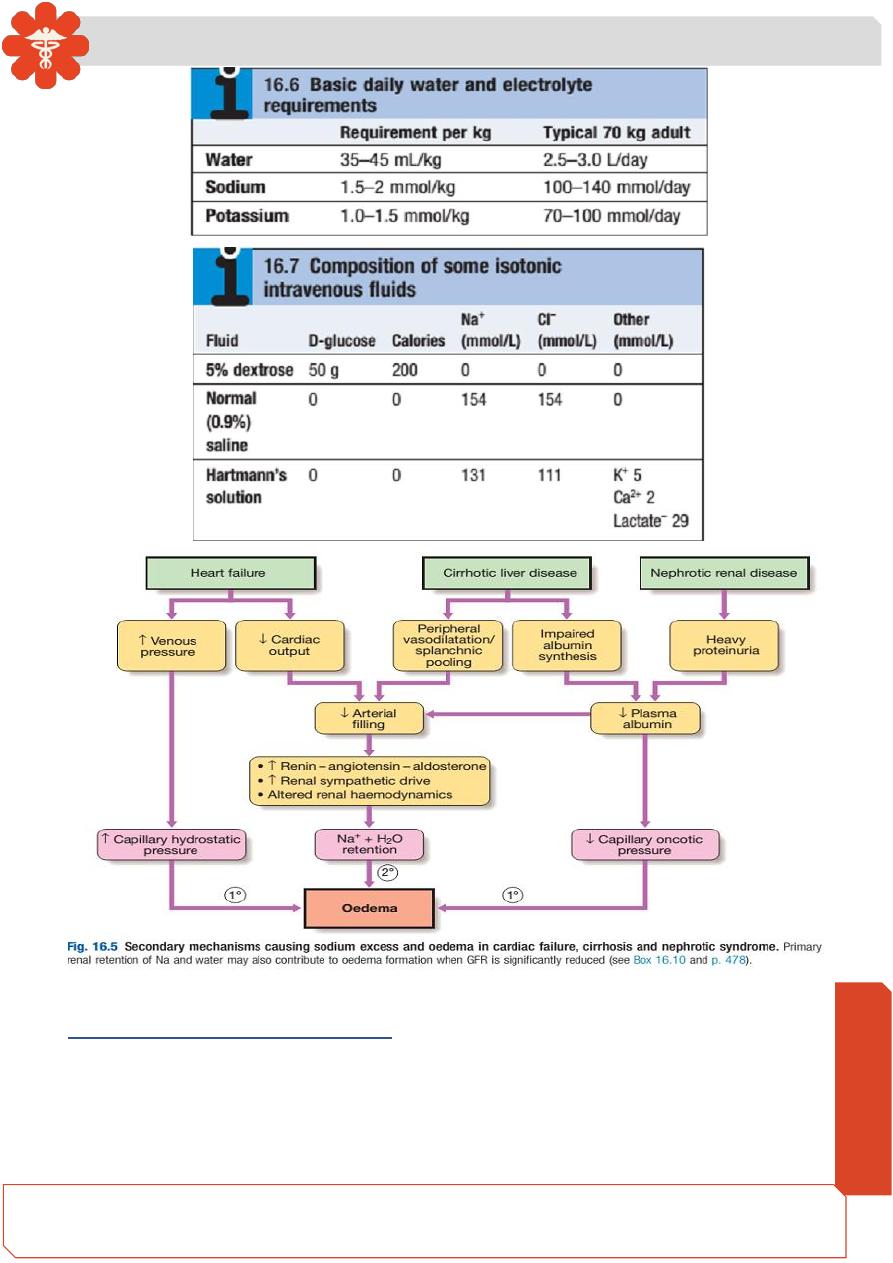

Intravenous fluid therapy:

The choice of fluid and the rate of administration depend on the clinical circumstances,

as assessed at the bedside and from laboratory data.

N

eed S

om

e H

el

p?

Medicine

Notes…

2

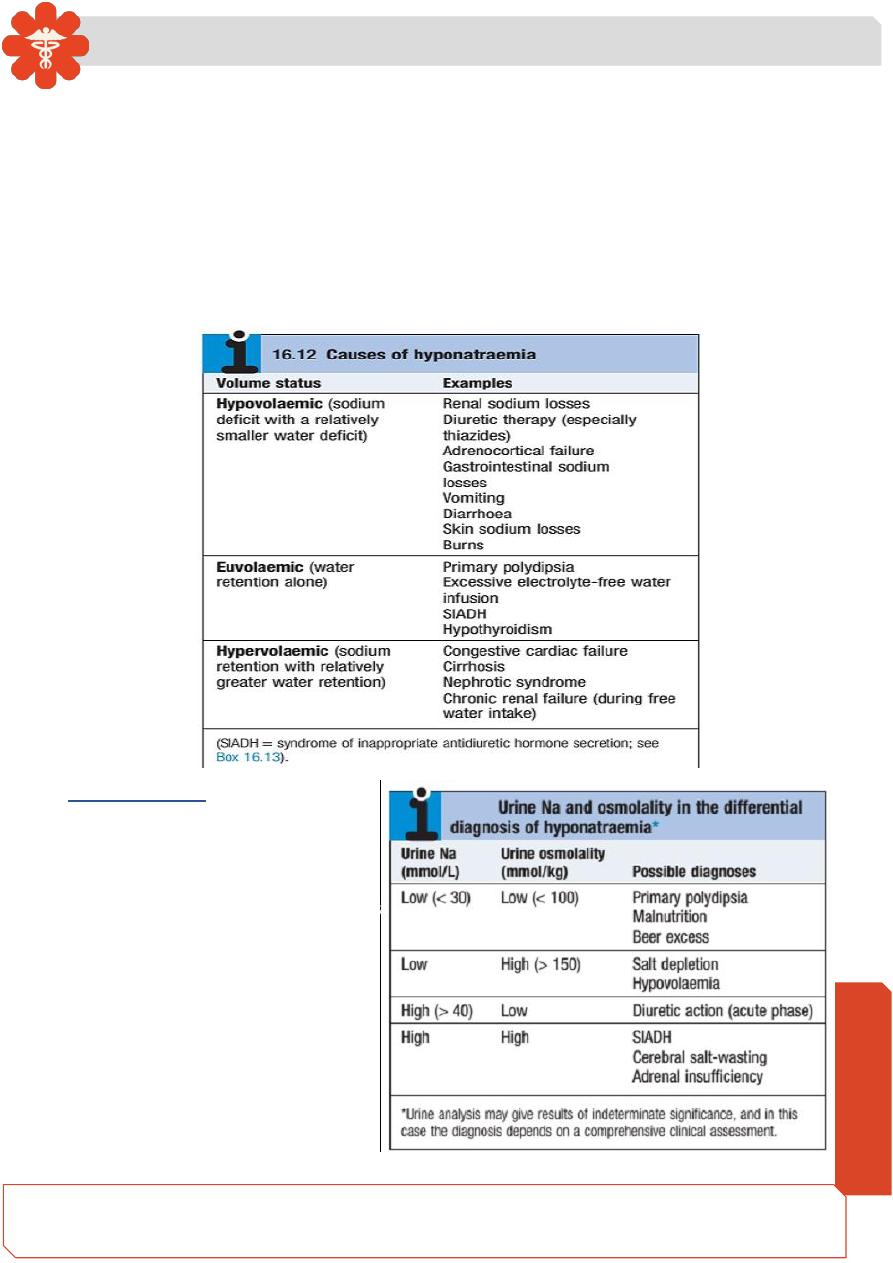

Hyponatraemia:

Aetiology and clinical assessment:

Hyponatraemia (plasma Na <135 mmol/L) is a common electrolyte abnormality, which is

often asymptomatic but which can also be associated with profound disturbances of

cerebral function, manifesting as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, confusion, lethargy,

seizures and coma.

Medicine

Notes…

3

The likelihood of symptoms occurring is related more to the speed at which electrolyte

abnormalities develop rather than their severity. When plasma osmolality falls rapidly,

water flows into cerebral cells, which become swollen and ischaemic. However, when

hyponatraemia develops gradually, cerebral neurons have time to respond by reducing

intracellular osmolality, through excreting potassium and reducing synthesis of

intracellular organic osmolytes .

The osmotic gradient favouring water movement into the cells is thus reduced and

symptoms are avoided.

Investigations:

Plasma and urine electrolytes and

osmolality are usually the only

tests required to classify the

hyponatraemia

Medicine

Notes…

4

Management

The treatment of hyponatraemia is critically dependent on its rate of development, severity

and underlying cause. If hyponatraemia has developed rapidly (over hours to days), and

there are signs of cerebral oedema such as obtundation or convulsions, sodium levels

should be restored to normal rapidly by infusion of hypertonic (3%) sodium chloride. A

common approach is to give an initial bolus of 100 mL, which may be repeated once or

twice over the initial hours of observation, depending on the neurological response and

rise in plasma sodium.

On the other hand, rapid correction of hyponatraemia that has developed slowly

(over weeks to months) can be hazardous, since brain cells adapt to slowly developing

hypo osmolality by reducing the intracellular osmolality, thus maintaining normal cell

volume .

Under these conditions, an abrupt increase in extracellular osmolality can lead to

water shifting out of neurons, abruptly reducing their volume and causing them to detach

from their myelin sheaths.

The resulting

‘myelinolysis’ can produce permanent structural and functional

damage to mid-brain structures, and is generally fatal.

The rate of correction of the plasma Na concentration in chronic asymptomatic

hyponatraemia should not exceed 10 mmol/L/day, and an even slower rate is generally

safer.

Medicine

Notes…

5

The underlying cause should be treated. For hypovolaemic patients, this involves

controlling the source of sodium loss, and administering intravenous saline if clinically

warranted. Patients with dilutional hyponatraemia generally respond to fluid restriction in

the range of 600

–1000 mL/day, accompanied where possible by withdrawal of the

precipitating stimulus (such as drugs causing SIADH).

If the response of plasma sodium is inadequate, treatment with demeclocycline

(600

–900 mg/day) may be of value by enhancing water excretion, through its inhibitory

effect on responsiveness to ADH in the collecting duct. An effective alternative for subjects

with persistent hyponatraemia due to prolonged SIADH is oral urea therapy (30

–45

g/day), which provides a solute load to promote water excretion. Where available, oral

vasopressin receptor antagonists such as tolvaptan may be used to block the ADH-

mediated component of water retention in a range of hyponatraemic conditions.

Hypervolaemic patients with hyponatraemia need treatment of the underlying condition,

accompanied by cautious use of diuretics in conjunction with strict fluid restriction.

Potassium-sparing diuretics may be particularly useful in this context where there is

significant secondary hyperaldosteronism.

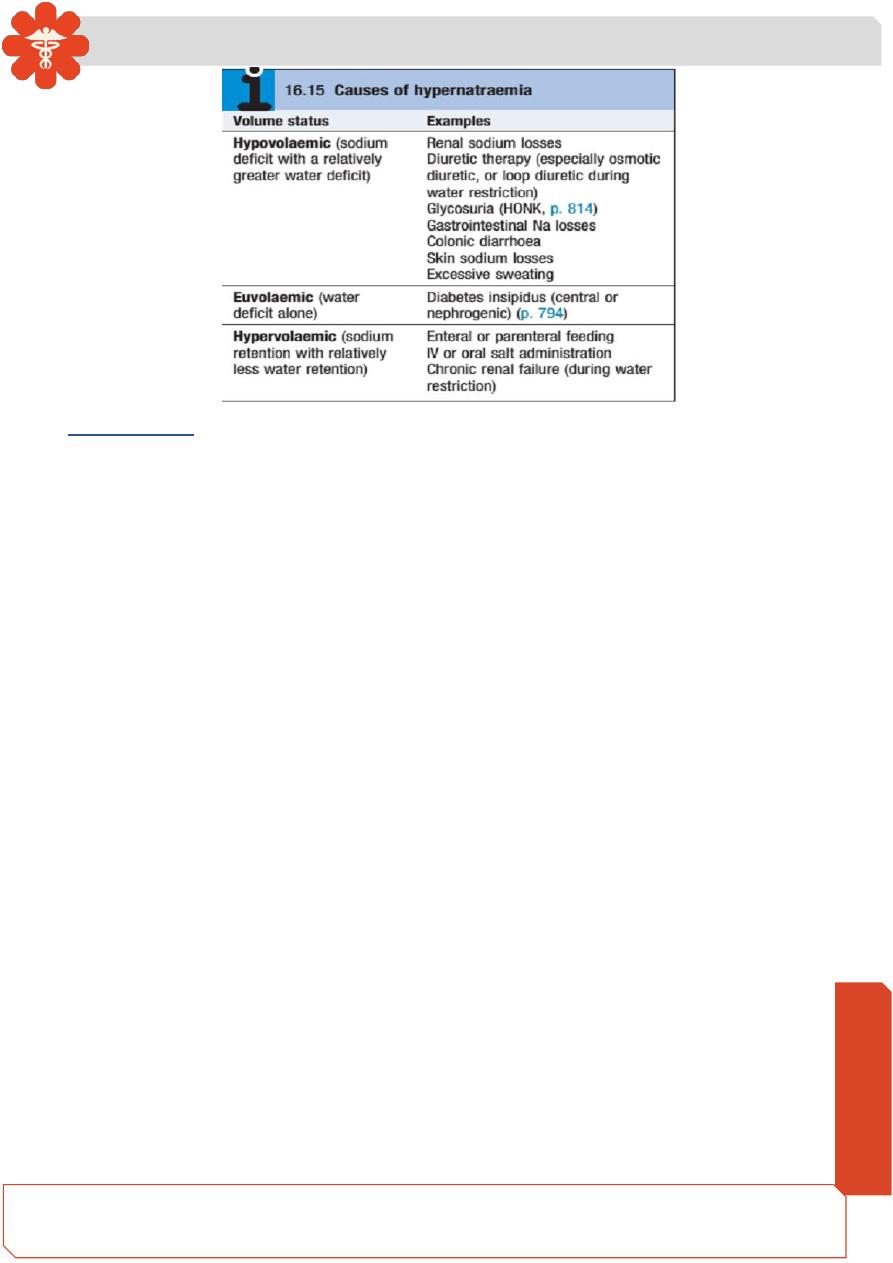

Hypernatraemia:

Aetiology and clinical assessment:

Just as hyponatraemia represents a failure of the mechanisms for diluting the urine during

free access to water, so hypernatraemia (plasma Na >148 mmol/L) reflects inadequate

concentration of the urine in the face of restricted water intake.

Patients with hypernatraemia generally have reduced cerebral function, either as a

primary problem or as a consequence of the hypernatraemia itself, which results in

dehydration of neurons and brain shrinkage. In the presence of an intact thirst mechanism

and preserved capacity to obtain and ingest water, hypernatraemia may not progress very

far. If adequate water is not obtained, dizziness, confusion, weakness and ultimately coma

and death can result.

Medicine

Notes…

6

Management:

Treatment of hypernatraemia depends on both the rate of development and the underlying

cause.

If there is reason to think that the condition has developed rapidly, neuronal shrinkage

may be acute and relatively rapid correction may be attempted. This can be achieved by

infusing an appropriate volume of intravenous fluid (isotonic 5% dextrose or hypotonic

0.45% saline) at an initial rate of 50

–70 mL/hour. However, in older, institutionalised

patients it is more likely that the disorder has developed slowly, and extreme caution

should be exercised in lowering plasma sodium to avoid the risk of cerebral oedema.

Where possible, the underlying cause should also be addressed.