Childhood asthma

د. حسين محمد جمعةاختصاصي الامراض الباطنة

البورد العربي

كلية طب الموصل

2010

Learning outcomes

After completing this module you should be able to:Consider which inhaler device is most suitable for a child with asthma

Use steroids more judiciously in children with viral episodic wheezing

Use high doses of steroids to gain initial control in a child with asthma but step down the dose to reduce the risk of complications

Refer children who are taking high dose inhaled steroids to a specialist to consider the implications for their long term growth.

About the author

Alexander Williams is a GP at St Thomas Health Centre in Exeter. He was formerly a registrar in general and respiratory medicine at Torbay Hospital and, until recently, was hospital practitioner in respiratory medicine at Wonford Hospital, Exeter.Why I wrote this module

"I wrote this module so that I could better understand the diagnosis and treatment of childhood asthma. I learnt that childhood asthma can be categorised into classic childhood asthma (often associated with atopy) and viral episodic wheezing (often triggered by viral infections). The two forms are treated differently."

Key points

Diagnosis

Childhood asthma is characterised by chronic or recurrent cough or wheeze.

The diagnosis can be confirmed with peak flow measurements and spirometry in children old enough to perform these measurements.

A therapeutic trial of medications also may be helpful

Management

The British Thoracic Society recommends a stepwise approach to the treatment of asthma.Children aged 5-12 years

Step 1: mild intermittent asthma

Start the child on an inhaled short acting beta2 agonist as needed.

Step 2: regular preventer therapy

Add in an inhaled steroid at 200-400 µg/day (beclometasone or equivalent). Use a starting dose of inhaled steroid appropriate for the severity of disease: the usual starting dose is 200 µg/day.

Step 3: add on therapy

You should add inhaled long acting beta2 agonistsIf the patient has a good response to the long acting beta2 agonist, continue the drug

If the patient has benefit from long acting beta2 agonist, but control is still inadequate, continue the drug and increase the dose of inhaled steroid to 400 µg/day

If the patient has no response to long acting beta2 agonist, stop it and increase the inhaled steroid dose to 400 µg/day.

If control is still inadequate, try other treatments: for example, leukotriene receptor antagonists or slow release theophylline.

Step 4: persistent poor control

Increase inhaled steroid up to 800 µg/day.

Step 5: continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

Start daily steroid tablets at the lowest dose possible for adequate control and maintain high dose inhaled steroid (800 µg/day). Refer to a respiratory paediatrician.

Children aged <5 years

Step 1: mild intermittent asthmaStart an inhaled short acting beta2 agonist as needed.

Step 2: regular preventer therapy

Add in an inhaled steroid at a dose of 200-400 µg/day (beclometasone or equivalent) or a leukotriene receptor antagonist if an inhaled steroid cannot be used. Start at a dose of inhaled steroid appropriate for the severity of disease.

Step 3: add on therapy

In children aged 2-5 years, try a leukotriene receptor antagonist. In children aged <2 years, consider moving to step 4.Step 4: persistent poor control

Refer to a respiratory paediatrician.

Clinical tip

You should refer children to a respiratory paediatrician in the case of:• Diagnostic uncertainty

• Symptoms present from birth

• Excessive vomiting or posseting

• Severe upper respiratory tract infection

• Persistent wet cough

• Growth faltering

• Family history of unusual chest disease

• Unexpected clinical findings (for example, focal chest signs or dysphagia)

• Failure to respond to conventional treatment (for example, if a child needs to take inhaled steroids equivalent to >400 µg/day beclometasone or makes frequent use of steroid tablets)

• Parental anxiety.

What is it?

Childhood asthma is characterised by chronic or recurrent cough or wheeze. The diagnosis can be confirmed with peak flow measures and spirometry in children old enough to perform these measurements.

Who gets it?

Asthma is more common in children with a personal or family history of atopy.The highest incidence is in boys aged <5 years; the incidence then falls with increasing age

Many children wheeze, but this often gets better on its own (especially if no personal or family history of atopy is present)

The number of children with asthma has rocketed in recent years. About one in every eight children in the UK has asthma, compared with about one in 50 in the late 1970s. Why more children are getting asthma today than 20 years ago is not clear. People used to blame an increase in air pollution. But this seems unlikely because it has been found that many of the most polluted countries in the world, such as China and Eastern European countries, have low rates of asthma, whereas countries with the best air quality, such as New Zealand, have high rates of asthma.

One of the most popular explanations at the moment is the "hygiene hypothesis." This blames increasing asthma rates on cleaner homes, which have meant that children get fewer infections than they used to. Some scientists think that childhood infections help to build up the immune system, and because children are getting fewer infections, they have less protection against asthma.

Asthma attacks usually result from:

• Infection

• House dust mites

• Pets

• Anxiety

• Tobacco smoke.

How do I diagnose it?

Childhood asthma is diagnosed by the presence of reversible episodes of airflow obstruction in the absence of alternative diagnoses.The differential diagnosis of asthma in infants and children is as follows:

• Upper airway diseases

• Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis

• Transient non-specific wheeze associated with viral infections

• Obstruction involving large airways

• Foreign body in trachea or bronchus

• Vocal chord dysfunction

• Obstruction involving small airways

• Viral bronchiolitis or obliterative bronchiolitis

• Cystic fibrosis.

History

Asthma is diagnosed from the patient's history. You should note the type and frequency of symptoms, whether there is a family history and whether there are any particular triggers.

Symptoms of asthma can be one or more of the following:

• Cough

• Wheeze

• Breathlessness

• Feeling of tightness in the chest.

Other points to remember in the diagnosis include:

Sleep may be disturbed by nocturnal dry coughCough may be present in the absence of wheeze

A therapeutic trial of drugs may be helpful

Question the diagnosis if the treatment is not working.

The diagnosis can be confirmed with peak flow measurements and spirometry in children old enough to do these. Spirometry can be undertaken in children from the age of 5 upwards.

Examination

Most children with asthma look completely normal. Children with severe asthma may have hyperinflation and chest deformity (for example, pigeon chest). Wheeze may be audible when you listen to the chest.Unilateral chest signs should raise the suspicion of chronic lung disease (such as cystic fibrosis) or, rarely, obstruction from a foreign body (such as a peanut). If the child is failing to thrive, suspect chronic lung disease.

Investigations

Older children may be able to measure their peak expiratory flow rate and record the values in a peak flow diary. In patients with asthma, peak flow is often variable and gets worse at night.A chest x ray may be warranted if you suspect suppurative lung disease.

How is it treated?

Non-drug measures

Avoiding house dust mites

Benefits

Methods to reduce levels of house dust mites have not been proved to reduce symptoms of asthma.

Side effects

No ill effects result from reducing levels of house dust mites; however, attempts to reduce levels can cause upheaval in the home.

Evidence

No good evidence supports the theory that allergen avoidance may help reduce disease severity. One review found that methods to reduce levels of house dust mites did not help patients with asthma and sensitivity to dust mites.Avoidance of other exacerbating factors

No evidence confirms that removing pets from the house helps children with asthma who have a pet allergy, but many experts still recommend this approach. If there is no pet then it might be a good idea to advise against getting one.Cessation of smoking by parents can reduce the severity of their children's asthma.

Other measures

A Cochrane review found that family therapy (which is organised through child and adolescent services to address the needs of families under stress) may be a useful adjunct to drugs in difficult childhood asthma.Sport and exercise should be encouraged. Inhalers should be available to prevent deterioration in symptoms during exercise.

Drug measures

The British Thoracic Society recommends a stepwise approach to drug treatment.Control of asthma is assessed against these standards:

• Minimal symptoms during day and night

• Minimal need for reliever drugs

• No exacerbations

• No limitation of physical activity

• Normal lung function (in practical terms, forced expiratory volume in one second or peak expiratory flow >80% predicted or best, or both).

A stepwise approach aims to:

Abolish symptoms as soon as possible

Optimise peak flow by starting treatment at the level most likely to achieve this.

Patients should start treatment at the step most appropriate for the initial severity of their asthma. The aim is to achieve early control and then to maintain control by stepping up treatment as necessary and stepping down when control is good.

Symptom relief

Inhaled short acting beta2 agonistsBenefits

Inhaled short acting beta2 agonists are the most effective drugs for relieving acute bronchospasm. They are the drug of choice for step 1 and just before exercise to prevent exercise induced wheeze.

Side effects

Common side effects in children include tachycardia and hyperactivity. Hypokalaemia can occur with excessive doses.

Evidence

It is unethical to run trials that measure the effects of short acting beta2 agonists on symptom control. More recently, research has focused on whether short acting beta2 agonists have a role in the prophylaxis of asthma. One systematic review showed that regular use of short acting beta2 agonists did not prevent exacerbations of asthma, and that patients who used their inhaler as needed had better symptom control than those who used it continuously.Dose

Use the minimum dose necessary on an as required basis.

Side effects

Oropharyngeal side effects of inhaled corticosteroids (sore throat, hoarse voice, and candidiasis) are uncommon at low doses, especially if a spacer is used and if the mouth is rinsed after inhalation. At higher doses, systemic absorption can occur.Systemic absorption is more likely to occur with beclometasone than the other steroids. Two systematic reviews of studies with long term follow up found no evidence of growth retardation in children treated with low dose inhaled corticosteroids. Short term studies, however, found that growth velocity was reduced and that high doses of inhaled steroids particularly can restrict growth.

Two observational studies found no evidence that inhaled steroids affect bone metabolism in children. Two cross sectional studies found no evidence that they cause cataracts in children.

Evidence

One systematic review compared inhaled steroids with placebo. This showed improved symptom scores, reduced use of beta2 agonists, reduced use of oral corticosteroids, and improved peak flow rates in those who took inhaled corticosteroids. Inhaled corticosteroids were better at improving symptoms and lung function than inhaled long acting beta2 agonists, oral leukotriene receptor antagonists, sodium cromoglycate, and nedocromil.Dose

Beclometasone is a commonly used inhaled steroid that may be started at 200 µg/day. Fluticasone is about twice as potent per microgram as budesonide and beclometasone: 100 µg fluticasone is equivalent to 200 µg budesonide or beclometasone. If asthma is poorly controlled on low dose inhaled corticosteroids, common practice is to increase the dose. The only CFC free form of beclometasone dipropionate currently available is Clenil Modulite. Qvar is NOT licensed in children <12 years. The MHRA has advised “that CFC-free beclometasone dipropionate inhalers should be prescribed by brand name.”Mast cell stabilisers

BenefitsProphylactic inhaled nedocromil improves symptoms and lung function in children with asthma; however, inhaled nedocromil is less effective than inhaled steroids. It is not specifically included in the British Thoracic Society stepwise approach. It is rarely used nowadays.

Side effects

Reported side effects include an unpleasant taste, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Evidence

One randomised controlled trial (1041 children) compared nedocromil, budesonide, and placebo in children with mild to moderate asthma. Nedocromil reduced the number of urgent care visits and courses of prednisolone compared with placebo, but children who took inhaled budesonide had better control of symptoms and needed fewer hospital stays.Dose

A dose of 4 mg nedocromil may be given four times daily; when control is achieved, it may be possible to reduce the frequency to twice daily.

Theophyllines

BenefitsProphylactic oral theophylline improves symptoms and lung function in children with asthma. The British Thoracic Society recommends that theophylline is tried at step 3 in children aged 5-12 years who are symptomatic despite taking 400 µg/day of inhaled steroid and a long acting beta2 agonist (the latter should be stopped before theophylline is started).

Side effects

Patients who take theophylline need to be monitored for potential but serious side effects, including arrhythmias and convulsions. Oral theophylline is associated with a higher frequency of headache, gastric irritation, and tremor than inhaled beclometasone.

Evidence

One randomised controlled trial compared oral theophylline with inhaled corticosteroids. Both treatments provided good symptom control, but children who took corticosteroids needed fewer additional drugs than those on theophylline.

Dose

In a child aged >6 years, theophylline 125 mg may be given every 12 hours.

Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists

BenefitsOral leukotriene receptor antagonists improve some symptoms of asthma in children. In children with asthma that is poorly controlled with inhaled steroids alone, introduction of a leukotriene antagonist can improve lung function and reduce exacerbations.

In children aged <5 years, oral leukotriene antagonists can be started at step 2 if inhaled steroids cannot be tolerated. Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists should be used at step 3 in children aged 5-12 years who are still symptomatic despite taking 400 µg/day of inhaled steroid and a long acting beta2 agonist (the latter should be stopped before leukotriene receptor antagonists are started).

Side effects

Side effects include gastrointestinal disturbance, thirst, skin reactions, and sleep disturbances. Leukotriene receptor antagonists have been associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome (asthma, rhinitis, sinusitis, systemic vasculitis, and eosinophilia). In many cases, such reactions followed reduction or withdrawal of oral corticosteroids. The Committee for Safety of Medicines advised that you should be alert to the development of eosinophilia, vasculitic rash, worsening pulmonary symptoms, cardiac complications, or peripheral neuropathy in patients prescribed leukotriene receptor antagonists.Evidence

One trial in 279 patients who were taking budesonide compared the effects of adding montelukast to adding placebo. Montelukast improved forced expiratory volume and peak expiratory flow rate and reduced the number of days with asthma exacerbations.Dose

Montelukast may be given as 4 mg at bedtime in children aged 2-5. It may be given as 5 mg daily at bedtime in children aged 6-14 years. Montelukast is available as a pink, cherry flavoured chewable tablet.

Learning bite

Zafirlukast is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairmentLong acting beta2 agonists

Benefits

Prophylactic long acting beta2 agonists improve symptoms and lung function in children with asthma compared with placebo. The British Thoracic Society guidelines advise that long acting beta2 agonists be used at step 3 in children aged 5-12 years.

Side effects

Side effects of long acting beta2 agonists include tachycardia, tremor, and hypokalaemia.

Evidence

Two randomised controlled trials compared treatment with inhaled long acting beta2 agonists with treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (beclometasone versus salmeterol) in 308 children.The first smaller study found that beclometasone was more effective than salmeterol at improving lung function and the need for short acting beta2 agonists. Children treated with the corticosteroid had fewer exacerbations. Both treatments improved symptom scores. In the second study, 241 children were randomised to receive beclometasone, salmeterol, or placebo. Both salmeterol and beclometasone improved lung function, but the corticosteroid was more effective as it reduced exacerbations and the need for bronchodilator while salmeterol did not.Dose

The dose of salmeterol is 50 µg twice a day.

Choice of inhaler

Selecting an appropriate device is fundamental to the success of asthma management. You may prescribe a dose of medication, but the amount that reaches the target site in the airways depends on:The device used (suitability)

How it is used (technique)

The ease with which it is used (convenience and adherence)

Disease severity.

Patient choice is crucial, and the device should be appropriate for the age of the patient. Patients should be carefully instructed on how to use their inhaler device; a demonstration, observation of technique, and subsequent reinforcement should all be part of ongoing asthma management.

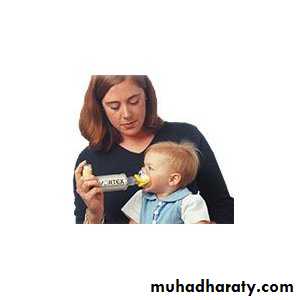

Large volume spacers nebulizer (for example, Volumatic or Nebuhaler) are most efficient when used properly. But smaller volume spacers (for example, Aerochamber) may be easier to carry, and this may help with compliance. In young children it is appropriate to use a spacer with a silicone mask and a small volume chamber that requires little inspiratory effort to open.

The stainless steel Nebuchamber nebulizer may be more efficient than plastic models, but it is not generic. The Aerochamber, on the other hand, fits most metered dose inhalers.

Spacers should be used when high doses of medication are needed, and to deliver bronchodilators in exacerbations.

nebulizer

(MDI) Metered Dose Inhaler Spacer

PARI Vortex Baby Whirl Duck Mask (1-2 yrs)

Medium Face MaskAeroChamber Plus Valved Holding Chamber / VHC

A nebulizer changes medication from a liquid to a mist so that it can be more easily inhaled into the lungs. Nebulizers are particularly effective in delivering asthma medications to infants and small children and to anyone who has difficulty using an asthma inhaler.

Baby using inhaler and spacer.

Benefits of a spacerIn order to properly use an inhaler without a spacer, one has to coordinate a certain number of actions in a set order (pressing down on the inhaler, breathing in deeply as soon as the medication is released, holding your breath, exhaling), and not all patients are able to master this sequence. Use of a spacer avoids such timing issues. Spacers slow down the speed of the aerosol coming from the inhaler, meaning that less of the asthma drug impacts on the back of the mouth and somewhat more may get into the lungs. Because of this, less medication is needed for an effective dose to reach the lungs, and there are fewer side effects from corticosteroid residue in the mouth.

Valves on a spacer (which technically makes it a holding chamber) cause the patient to inhale the contents of the spacer, but exhalation goes out into the air. The problem of co-ordinating an inspiration with a press of an inhaler is avoided, making use easier for children under 5 and the elderly. It also makes asthma medication easier to deliver during an attack. So use of spacer is advised by many.

Spacer Disadvantages

• A spacer can be bulky, limiting portability.• Devices along the inhalation path — such as a spacer — may cause the medication to deposit prior to reaching the patient and the patient can receive less than the measured dose.

Should I use a spacer/chamber device with my MDI/spray?A spacer/chamber or holding chamber is a device into which the inhaler is sprayed. Many inhaled devices delivering a liquid mist can be used with a spacer/chamber. The mist from the inhaler is sprayed into the spacer/chamber where the large and small particles separate. The large particles stick to the sides of the spacer/chamber while the small particles stay suspended for several seconds. This is a good thing because large particles are too big to enter the lungs. When large particles are inhaled, they only serve to create problems like a sore mouth, hoarse voice and fungal infections in the throat and mouth. Large particles are also absorbed into the body, increasing the chances of more side-effects. Conversely, the small particles stay suspended in the spacer/chamber, allowing you time to inhale the fine mist. This device has several advantages over using an MDI without a spacer/chamber. You no longer have to be as precise in coordinating activation of the spray from the canister while inhaling. You can first spray the medication into the chamber and then concentrate on inhaling the medication slowly.

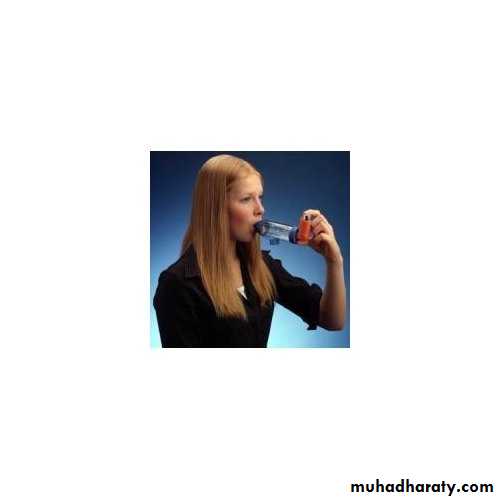

A Dry powder inhaler (DPI) is a device that delivers medication to the lungs in the form of a dry powder. DPIs are commonly used to treat respiratory diseases such as asthma, bronchitis, emphysema and COPD although DPIs have also been used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus Most DPIs rely on the force of patient inhalation to entrain powder from the device and subsequently break-up the powder into aerosol particles that are small enough to reach the lungs. For this reason, insufficient patient inhalation flow rates may lead to reduced dose delivery and incomplete deaggregation of the powder, leading to unsatisfactory device performance.

Thus, most DPIs have a minimum inspiratory effort that is needed for proper use and it is for this reason that such DPIs are normally used only in older children and adults.

A metered-dose inhaler (MDI) is a device that delivers a specific amount of medication to the lungs, in the form of a short burst of aerosolized medicine that is inhaled by the patient. It is the most commonly used delivery system for treating asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other respiratory diseases. The medication in a metered dose inhaler is most commonly a bronchodilator, corticosteroid or a combination of both for the treatment of asthma and COPD. Other medications less commonly used but also administered by MDI are mast cell stabilizers, such as (cromoglicate or nedocromil).

Viral episodic wheezing

Usually only acute wheezy episodes need to be treated. The best evidence supports the use of short acting inhaled beta2 agonists via a metered dose inhaler and spacer.Evidence on whether addition of inhaled ipratropium bromide is of benefit is conflicting. Evidence that oral steroids are helpful for treating acute wheeze in infants is conflicting. Evidence is weak and conflicting on whether inhaled steroids are valuable as prophylaxis against recurrent infant wheezing.

Follow up

Frequency of follow up depends on the severity of the presenting attack or the frequency of exacerbations. Children who rarely wheeze, or who wheeze only with viral infections, can be managed symptomatically. Regular review of patients as treatment is stepped up or down is important.What's the outlook?

In one study, children aged <12 years with asthma were followed up for 20 years:28% became asymptomatic

24% had occasional mild symptoms

27% had gone into remission for three years or more but had relapsed as adults

21% had not experienced remission for any period exceeding three months.

Factors associated with persistence include

Family history of atopy (a risk factor for recurring wheeze throughout childhood)Coexisting atopic illness (a risk factor for persistence of asthma through childhood)

Sex (male sex is a risk factor for asthma in prepubertal children but female sex is a risk factor for persistence of asthma in the transition from childhood to adulthood)

Viral episodic wheeze in infancy (often this is followed by wheeze in early childhood but most children outgrow this tendency to wheeze)

Age at presentation (the earlier the onset of wheeze, the better the prognosis. A "break point" is seen at two years: most children who present before this age are asymptomatic by age 6-11 years)

Increased frequency and severity of episodes (associated with recurrent wheeze in adulthood)

Exercise related symptoms in pre-school children

Poor lung function (correlates with persistence into adulthood).

Further information for patients and doctors can be found at the end of this module.

Getting the right start: national service framework for children

The national service framework provides guidelines for the design and delivery of hospital services around the needs of children and their families. It focuses on the safety of children while they are in hospital, the quality of hospital services for children, and the suitability of hospital settings for the care children receive.42

The framework includes guidance on long term and life threatening diseases such as asthma: it states that specialist paediatric clinics such as asthma clinics should have ready access to a mental health liaison service if this is required (for example, if the asthma is causing great psychosocial difficulty).

No specific national service framework currently exists for asthma.

General medical services contract for GPs

The new GMS contract allows practices to earn for performing certain actions that relate to asthma.Records

Practices can receive up to four points by achieving ASTHMA 1 (that is producing a register of patients with asthma, excluding patients with asthma who have been prescribed no asthma related drugs in the last 12 months).

Initial management

Practices can receive up to 15 points by achieving ASTHMA 8 (that is having a diagnosis confirmed by spirometry or peak flow measurement in 40-80% of patients aged ≥8 years diagnosed as having asthma from 1 April 2008).

Ongoing management

Practices can receive up to six points by achieving ASTHMA 3 (that is having a record of smoking status in the previous 15 months in 40-80% of patients with asthma aged 14-19 years).Practices can receive up to 20 points by achieving ASTHMA 6 (that is if up to 70% of patients with asthma have had an asthma review in the previous 15 months).

All these targets are relatively easy to achieve with good organisation. You can carry out an annual asthma review either in a structured asthma clinic or opportunistically when the patient attends the surgery for another problem.

Because the population with asthma is around 10% of a GP's list size, it may be difficult to recall all patients to clinics. So you should give priority to patients with troublesome symptoms or poor control (for example, recent admission, use of steroids or nebulisers, and polypharmacy) and those on regular prophylactic treatment.

Our practice has identified patients who have not used an inhaler for more than two years, and reclassified them as having a history of asthma so that they are excluded from the prevalence data.

Inhaled salmeterol

Long acting beta2 agonists can cause paradoxical bronchospasm.Prednisolone

Predisolone is least likely to cause paradoxical bronchospasm.

Inhaled budesonide

Inhaled steroids can cause paradoxical bronchospasm.

Salbutamol may be used in patients with hepatic impairment.

Salmeterol

Salmeterol may be used in patients with hepatic impairment.

Budesonide

Budesonide may be used in patients with hepatic impairment.

Zafirlukast

Zafirlukast is contraindicated in patients with hepatic impairment.

Ipatropium does not cause hypokalaemia.

Your answerCorrect answer

a.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

b.

Goodpasture's syndrome

c.

Churg-Strauss syndrome

• A 16 year old boy comes to your surgery with a rash. He has a past history of asthma and allergic rhinitis. He says his shortness of breath has worsened recently. On examination the rash appears to be vasculitic. You arrange a chest x ray: this shows a pulmonary infiltrate. Full blood count reveals marked peripheral eosinophilia. What is the most likely diagnosis?

•

Churg-Strauss syndrome is the most likely diagnosis as there is:

A history of asthma and rhinitisWorsening pulmonary symptoms

Peripheral eosinophilia

Pulmonary infiltrate

Vasculitic rash.

You should ask him whether he is taking a leukotriene receptor antagonist. You should also ask about whether he has recently stopped or reduced oral or inhaled steroids as this may unmask the disease

Your answer

Correct answera.

Give the salbutamol via a nebuliser

b.

Give it via a metered dose inhaler plus a spacer

• You diagnose a 4 year old boy with asthma. He has trouble using the salbutamol inhaler. What would you advise first?

You should first of all advise that he tries to use a metered dose inhaler plus a spacer.

Your answer

Correct answera.

Severe asthma

b.

First episode of wheezing at the age of 1

c.

Poor lung function tests

d.

Family history of asthma

• Which of the following factors suggests that a child with asthma will grow out of it in adulthood?

•

The earlier the age of onset the better the prognosis. A "break point" is seen at 2 years: most children who present before this age are asymptomatic by age 6-11 years.

علمني المطركيف اغسل همومي واحزانيوكيف اجدد حياتي كما تغسل قطرات المطراوراق الشجروتعيد لها الحياة