Renal trauma

classification, mechanism, gradingDr.Montadhar Almadani ( urology )

ClassificationBlunt injures –

Direct blow to the kidney.

- Rapid acceleration or rapid deceleration. –

A combination of the above.

Penetrating injuries Stab or gunshot injuries to the flank, lower chest, and anterior abdominal area may inflict renal damage.

Mechanism

The kidneys are retroperitoneal structures surrounded by perirenal fat, the vertebral column and spinal muscles, the lower ribs, and abdominal contents. They are, therefore, relatively protected from injury and a con- siderable degree of force is usually required to injure them (only 1.5–3% of trauma patients have renal injuries).Staging of the renal injury

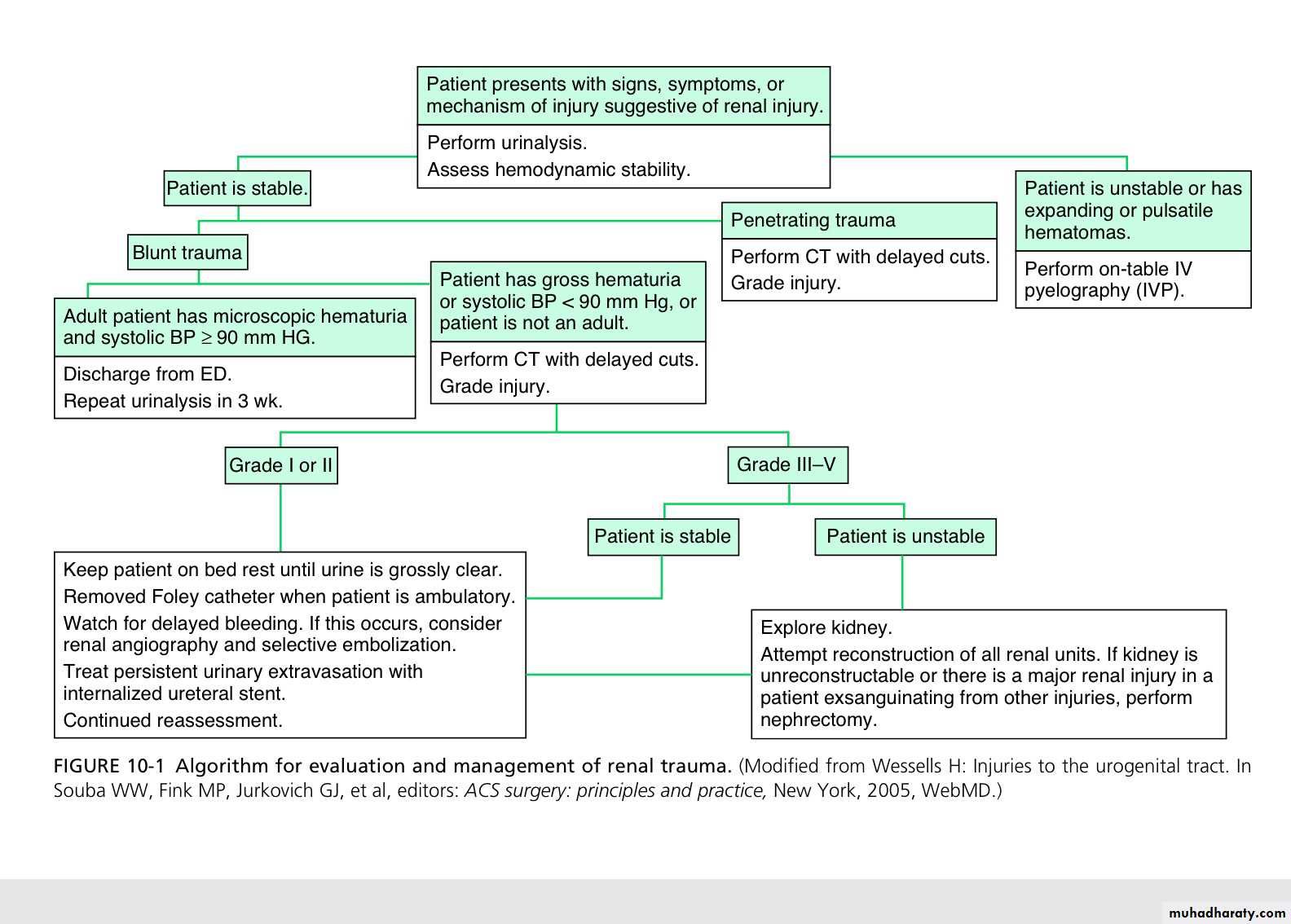

Using CT, renal injuries can be staged according to the AmericanAssociation for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Organ Injury Severity Scale. Higher inju- ry severity scales are associated with poorer outcomes.

Grade I

Contusion (normal CT) or subcapsular haematoma with no parenchymal laceration.

Grade II

<1cm deep parenchymal laceration of cortex, no extravasa- tion of urine (i.e. collecting system intact).

Grade III

>1cm deep parenchymal laceration of cortex, no extravasa- tion of urine (i.e. collecting system intact).

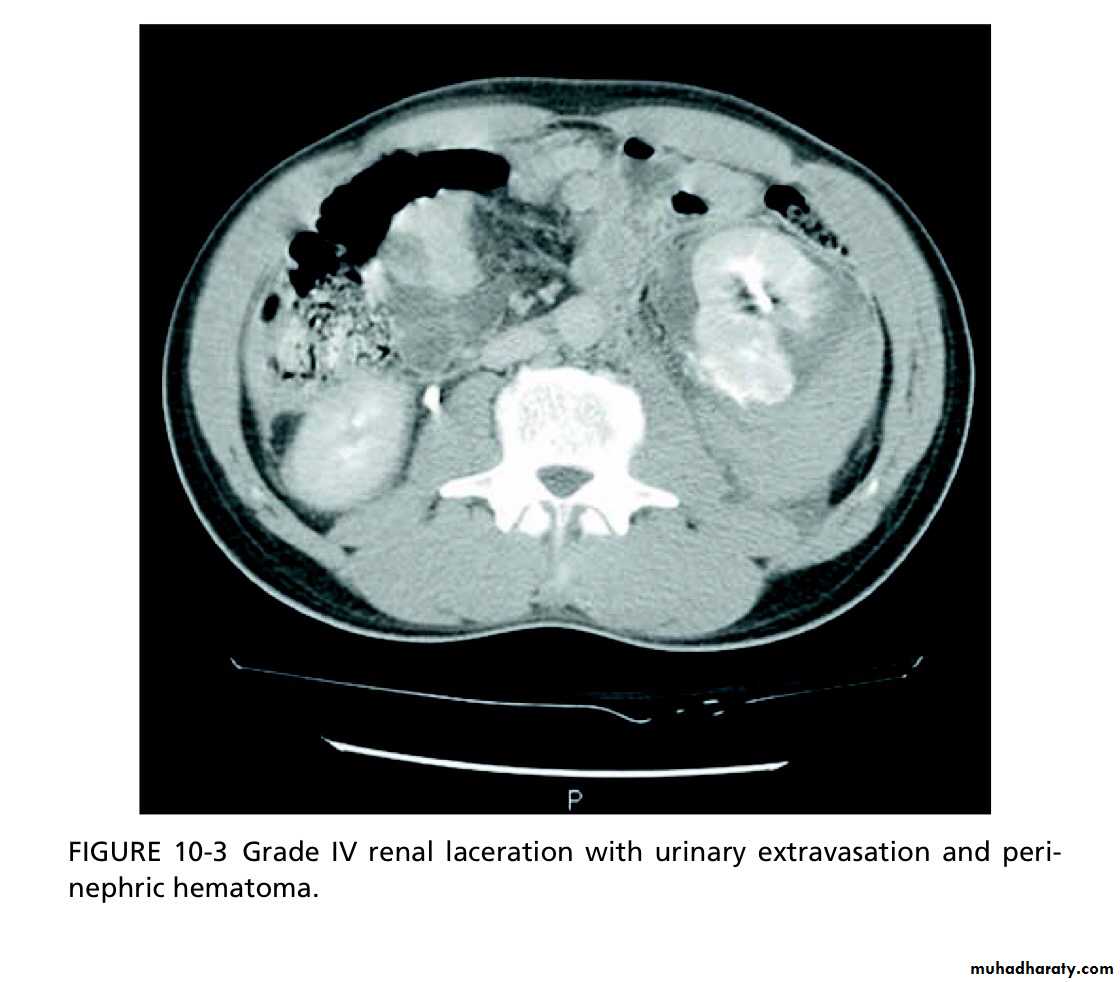

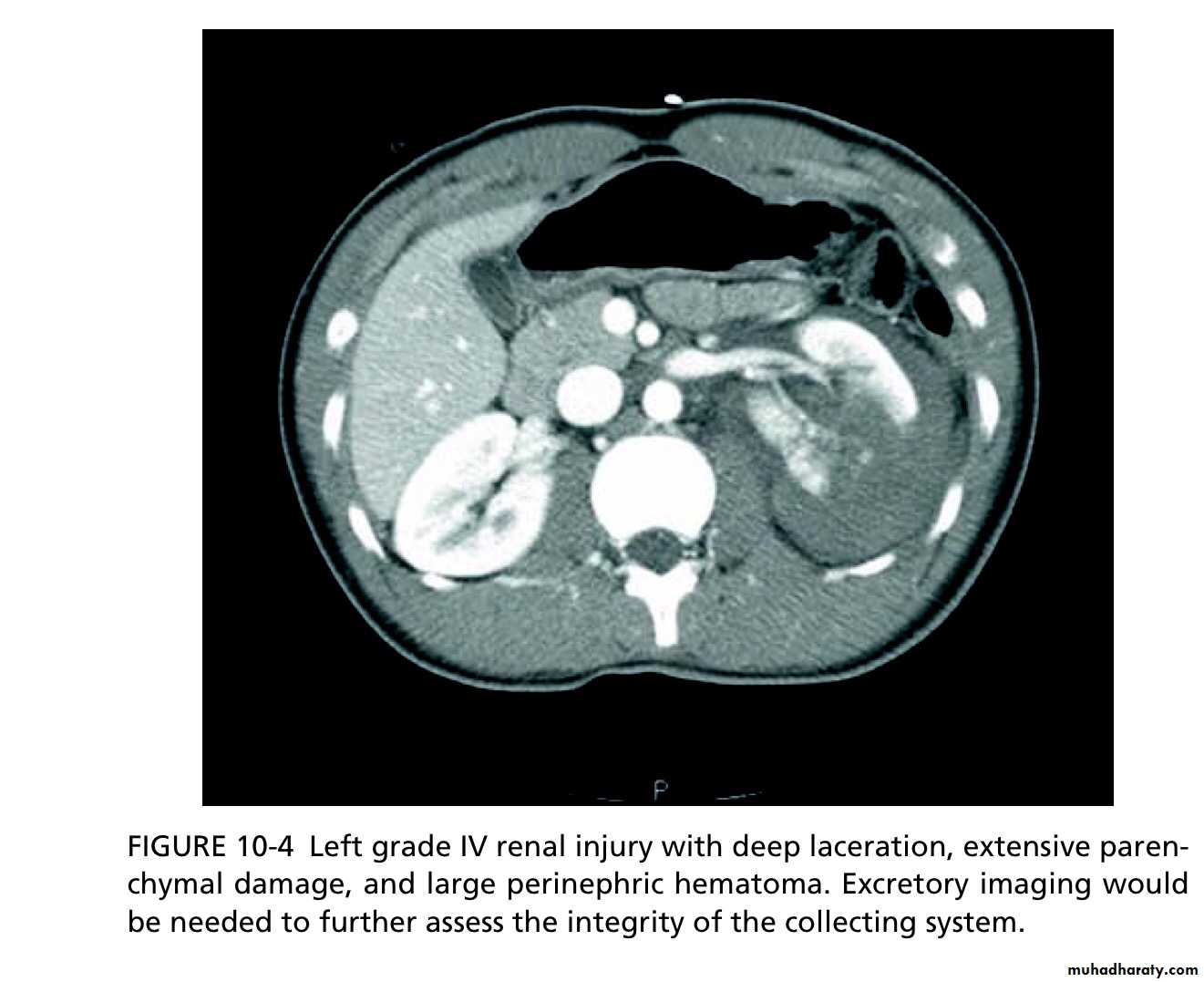

Grade IV

Parenchymal laceration, involving cortex, medulla and collect- ing system OR renal artery or renal vein injury with contained haemorrhage.

Grade V

Completely shattered kidney OR avulsion of renal hilum.

Paediatric renal injuries

The kidneys are said to be more prone to injury in children because of the relatively greater size of the kidneys in children, the smaller protective muscle mass and cushion of perirenal fat, and the more pliable rib cage.clinical and radiological assessment

The haemodynamically stable patient::::History: nature of trauma (blunt, penetrating)

Examination: pulse rate, systolic BP, respiratory rate, location of entry and exit wounds, flank bruising, rib fractures. The lowest recorded systolic BP is used to determine need for renal imaging.

Urinalysis: crucial for determining likelihood of renal injury and, therefore, of the need for radiological tests.

Haematuria (defined as >5 erythrocytes per high powered field or dipstick-positive) suggests the possibility of a renal injury; however, the amount of haematuria does not correlate consistently with the degree of renal injury.

Do FBC and serum chemistry profile.

Indications for renal imaging

- Macroscopic haematuria.

- Penetrating chest and abdominal wounds (knives, bullets).

- Microscopic (>5 RBCs per high powered field) or dipstick haematuria in a hypotensive patient (systolic BP <90mmHg recorded at any time since the injury).

- A history of a rapid acceleration or deceleration (e.g. fall from a height, high speed motor vehicle accident).

Falls from even a low height can cause serious renal injury in the absence of shock (systolic BP <90mmHg) and of haematuria (PUJ disruption prevents blood reaching the bladder).

- Any child with microscopic or dipstick haematuria who has sustained trauma.

The haemodynamically unstable patient

Haemodynamic instability may preclude standard imaging such as CT, the patient having to be taken to the operating theatre immediately to control the bleeding. In this situation, an on-table IVU is indicated if:• A retroperitoneal haematoma is found and/or

• - A renal injury is found which is likely to require nephrectomy.

treatment

Conservative (non-operative) managementMost blunt (95%) and many penetrating renal injuries (50% of stab injuries and 25% of gunshot wounds) can be managed non-operatively.

Dipstick or microscopic haematuria: if systolic BP since injury has always been >90mmHg and no history of acceleration or deceleration, imaging and admission is not required.

Macroscopic haematuria: in a cardiovascularly stable patient, having staged the injury with CT, admit for bed rest (no hard and fast rules as to dura- tion) and observation until the macroscopic haematuria, if present, resolves (cross-match in case BP drops); give antibiotics if urinary extravasation.

High-grade (IV and V) injuries: can be managed non-operatively if they are cardiovascularly stable. However, grade IV and, especially, grade V injuries often require nephrectomy to control bleeding (grade V injuries function poorly if repaired).

Surgical exploration

Is indicated (whether blunt or penetrating injury) if:- The patient develops shock which does not respond to resuscitation

with fluids and/or blood transfusion.

- The haemoglobin decreases (there are no strict definitions of what

represents a ‘significant’ fall in haemoglobin).

- There is urinary extravasation and associated bowel or pancreatic injury.

- Expanding perirenal haematoma (again the patient will show signs of

continued bleeding).

- Pulsatile perirenal haematoma.An expanding and/or pulsatile perirenal haematoma suggests a renal pedi- cle avulsion. Haematuria is absent in 20%.

Ureteric injuries: mechanisms and diagnosis

- External: rare—blunt (e.g. high-speed road traffic accidents, fall from a height; penetrating (knife or gunshot wounds). –Internal trauma (= iatrogenic): during pelvic or abdominal surgery, e.g. hysterectomy, colectomy, AAA repair; ureteroscopy. The ureter may be divided, ligated, or angulated by a suture; a segment excised or damaged by diathermy.

Symptoms and signs of ureteric injuryMay include:

- An ileus (due to urine within the peritoneal cavity).- Prolonged post-operative fever or overt urinary sepsis.

• Persistent drainage of fluid from drains, the abdominal wound, or the vagina. Send this for creatinine estimation. Creatinine level higher than that of serum = urine (creatinine level will be at least 300μmol/L).

- Flank pain if the ureter has been ligated.

- Abdominal mass, representing a urinoma (a collection of urine).

- Vague abdominal pain.

- The pathology report on the organ that has been removed may note the presence of a segment of ureter!

Investigation:

IVU or retrograde ureterogram. Ultrasonography may demonstrate hydronephrosis, but hydronephrosis may be absent when urine is leaking from a transected ureter into the retroperitoneum or peri- toneal cavity. The IVU usually shows an obstructed ureter or occasionally, a contrast leak from the site of injury.management

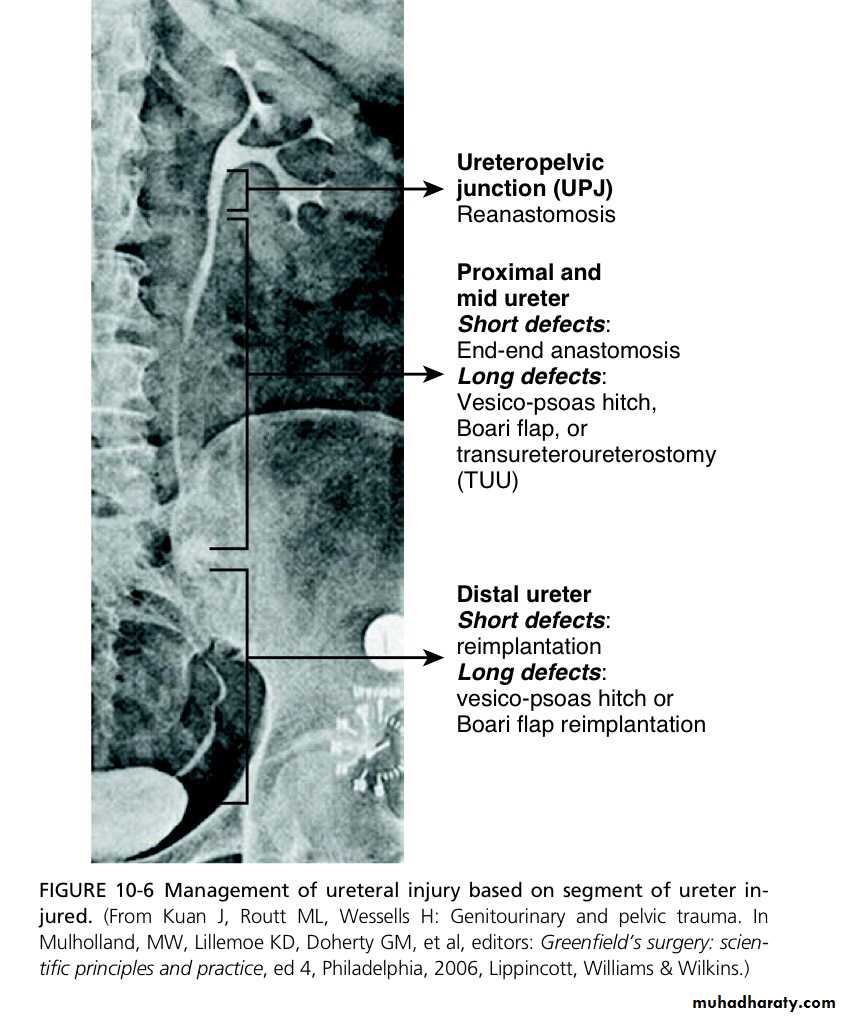

When to repair the ureteric injury:Generally, the best time to repair the ureter is as soon as the injury has been diagnosed.

Delay definitive ureteric repair when:

1- The patient is unable to tolerate a prolonged procedure under general anaesthesia.

2 - There is evidence of active infection at the site of proposed ureteric repair (infected urinoma).

Definitive treatment of ureteric injuries

The options depend on:1- Whether the injury is recognized immediately.

2- Level of injury.

3-Other associated problems.

The options are:

1-JJ stenting for 3–6 weeks (e.g. ligature injury recognized immediately).2-Primary closure of partial transection of the ureter.

3- Direct ureter to ureter anastomosis (primary uretero- ureterostomy)—if the defect between the ends of the ureter is of a length where a tension-free anastomosis is possible.

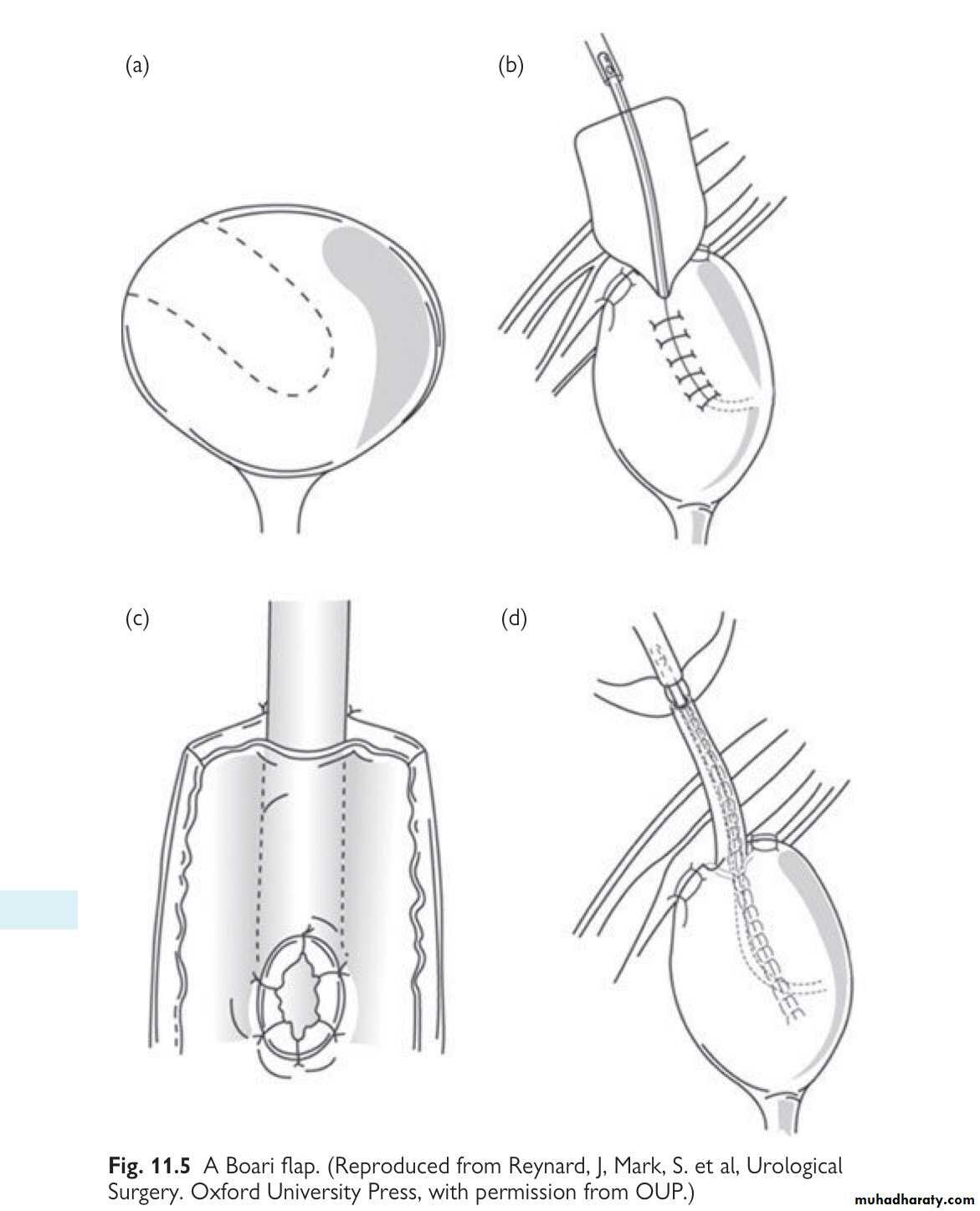

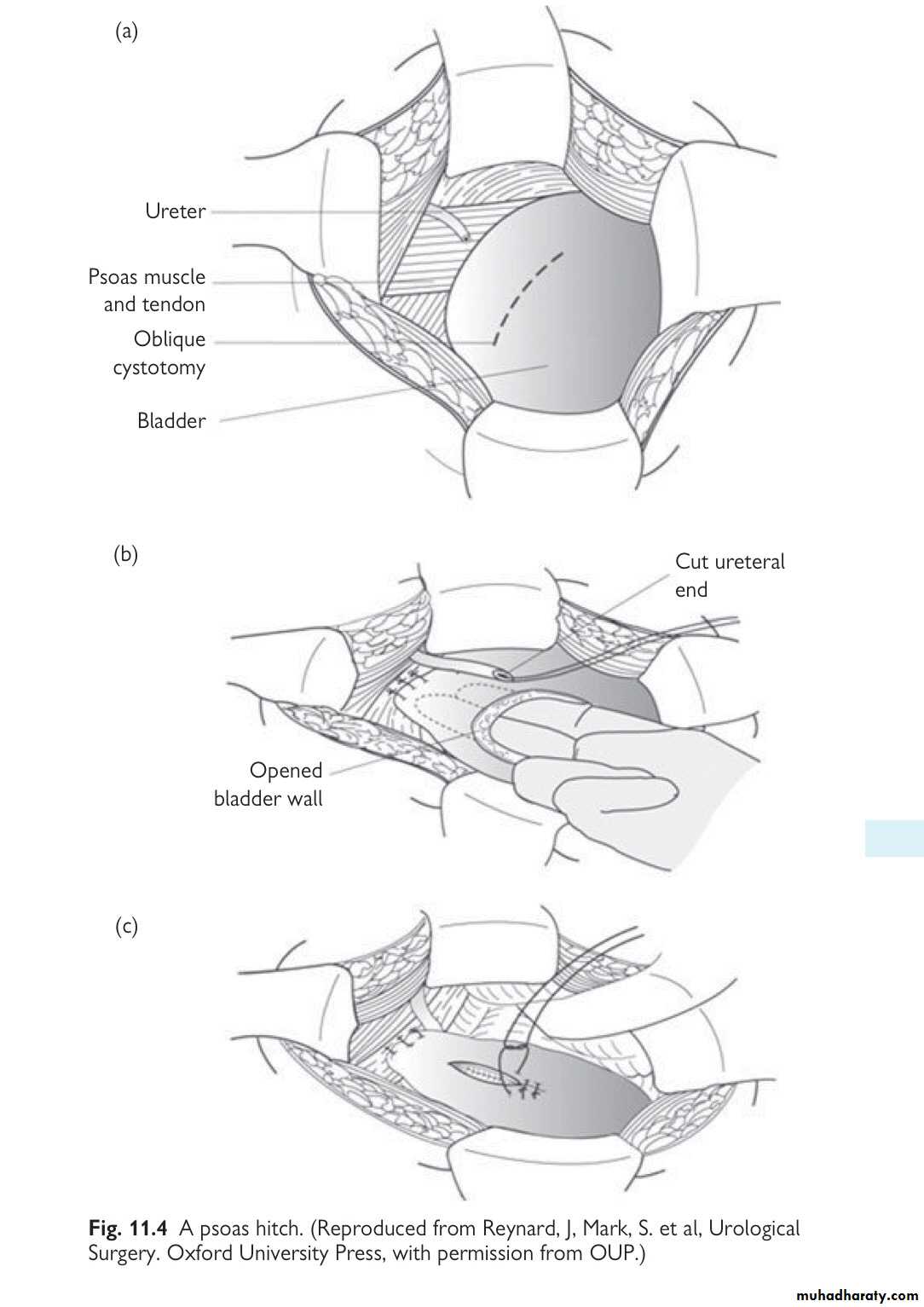

4-Reimplantation of the ureter into the bladder (uretero- neocystostomy), either using a psoas hitch or a Boari flap.

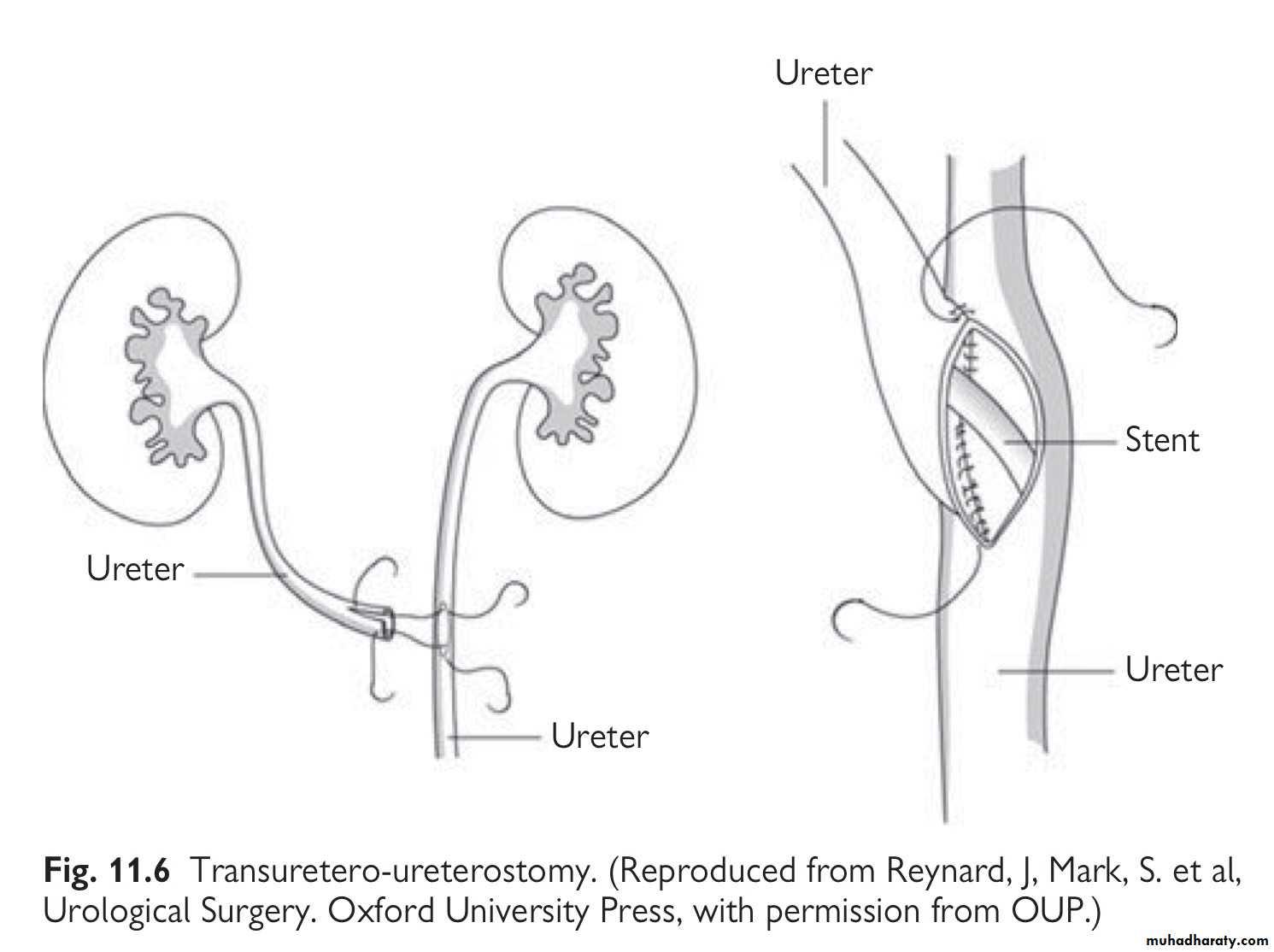

5-Transuretero-ureterostomy

6 - Autotransplantation of the kidney into the pelvis

7- Replacement of the ureter with ileum—where the segment of damaged ureter is very long.

8- Permanent cutaneous ureterostomy—where the patient’s life expectancy is very limited.

9- Nephrectomy.

General principles of ureteric repair

1- The ends of the ureter should be debrided so that the edges to be

anastomosed are bleeding freely.2-The anastomosis should be tension-free.

3- For complete transection, the ends of the ureter should be

spatulated to allow a wide anastomosis to be done.

4-A stent should be placed across the repair.

5- Mucosa to mucosal anastomosis should be done to achieve a

watertight closure.

6-Use 4/0 absorbable suture material.

7- A drain should be placed around the site of anastomosis.

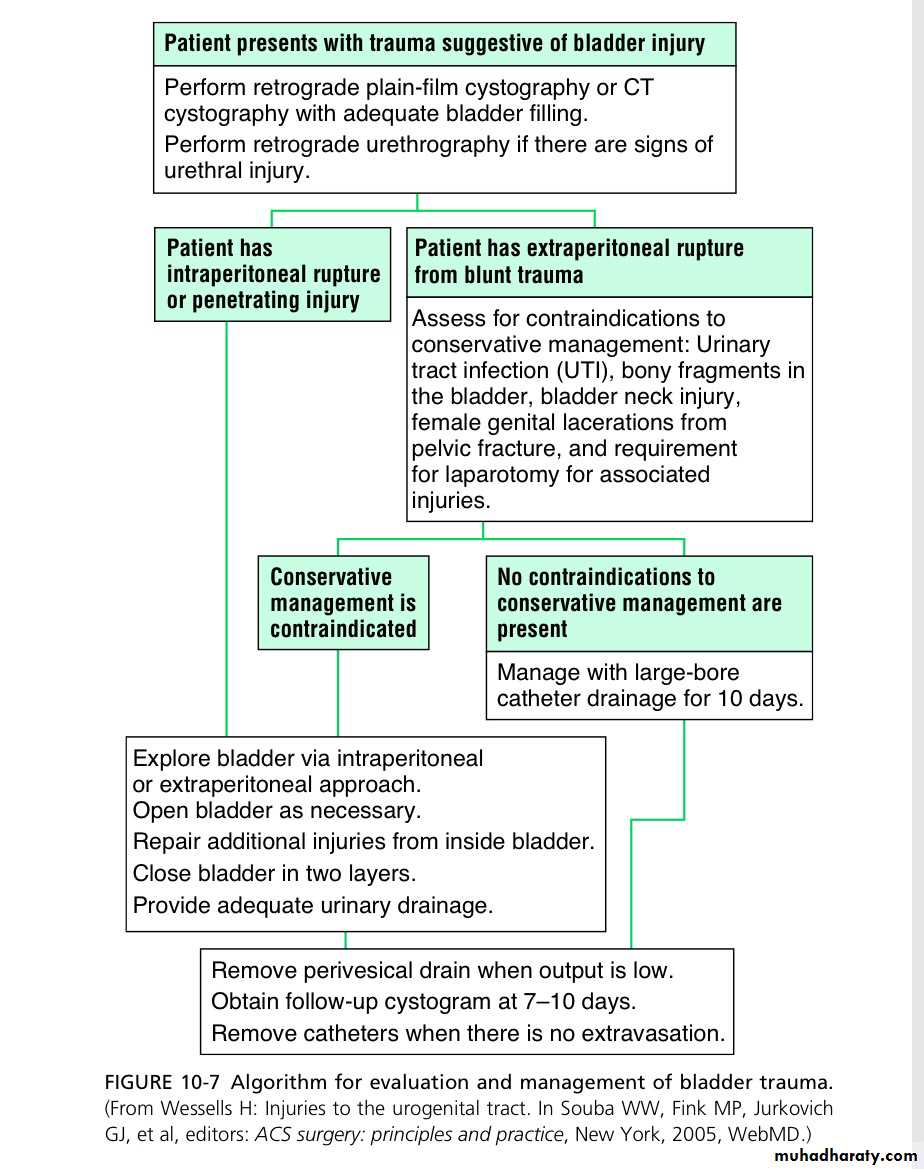

Bladder injuries

Situations in which the bladder may be injuredTURBT , cystoscopic bladder biopsy, TURP, cysto- litholapaxy, penetrating trauma to the lower abdomen or back, Caesarean section (especially as an emergency), blunt pelvic trauma—in association with pelvic fracture or ‘minor’ trauma in the inebriated patient, rapid de- celeration injury (e.g. seat belt injury with full bladder in the absence of a pelvic fracture), spontaneous rupture after bladder augmentation, total hip replacement (very rare).

Types of perforation

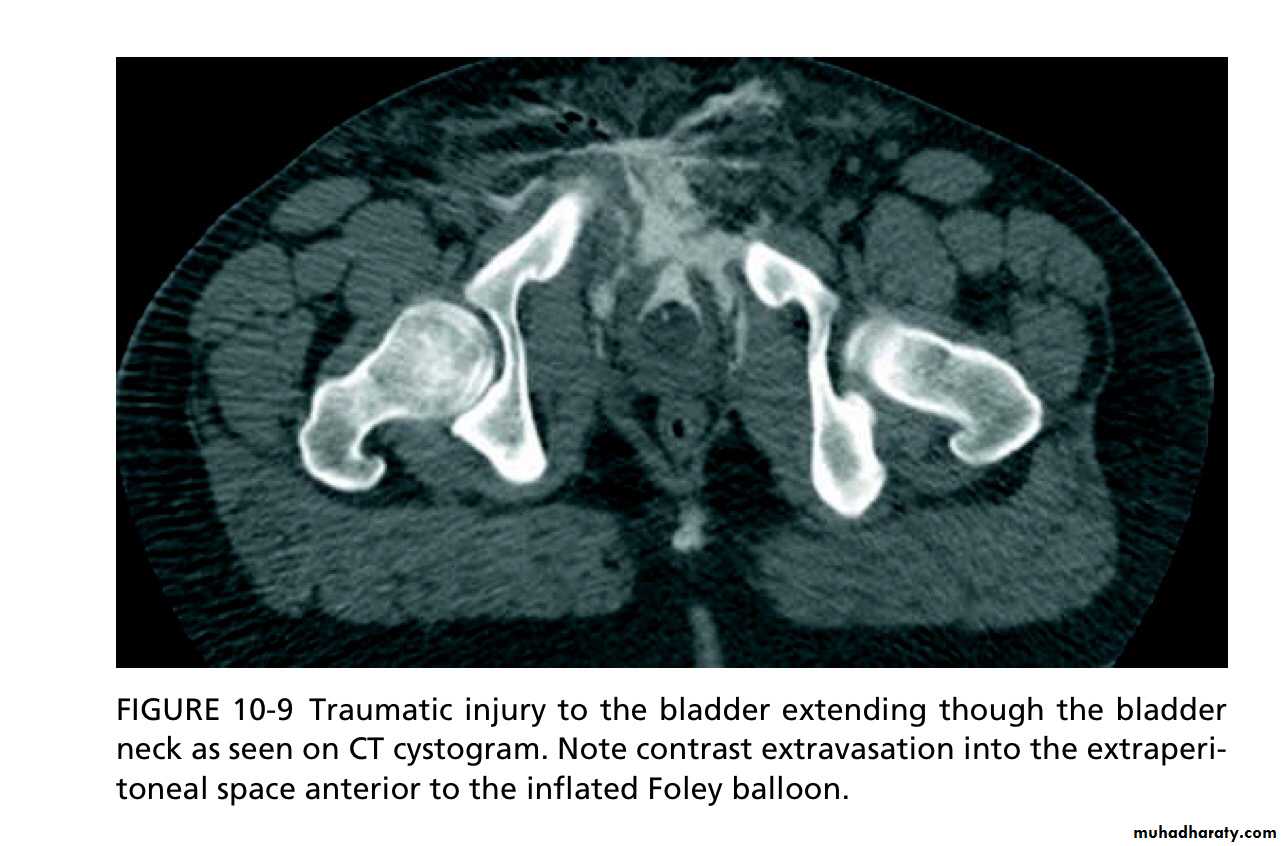

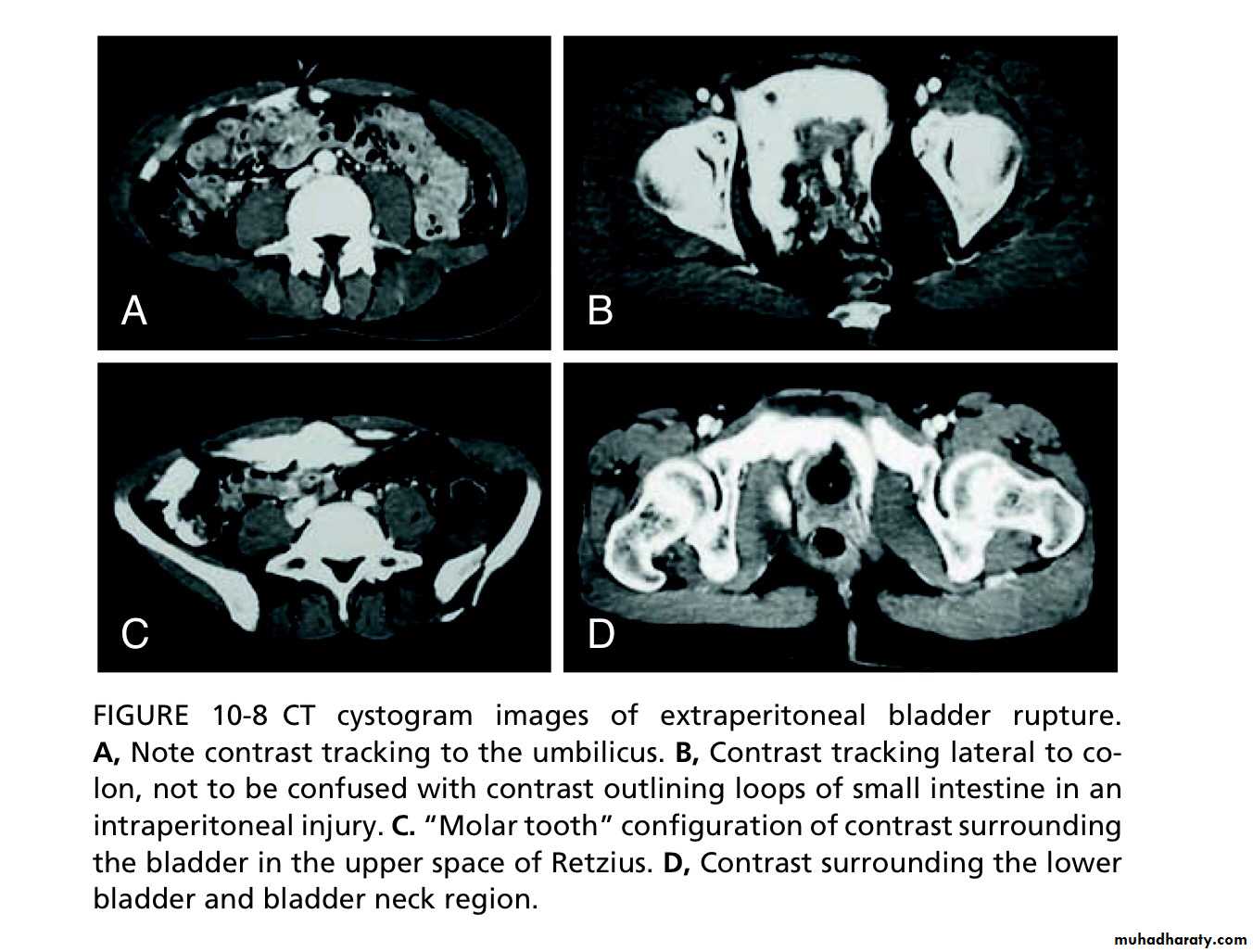

• Intraperitoneal perforation: the peritoneum overlying the bladder is breached, allowing urine to escape into the peritoneal cavity.• - Extraperitoneal perforation: the peritoneum is intact and urine escapes into the space around the bladder, but not into the peritoneal cavity.

Symptoms and signs

Suprapubic pain and tenderness.Difficulty or inability in passing urine.

Haematuria.

Abdominal distension.

Absent bowel sounds (indicating an ileus from urine in the peritoneal cavity).

#These symptoms and signs are an indication for a retrograde cystogram.

Imaging studies

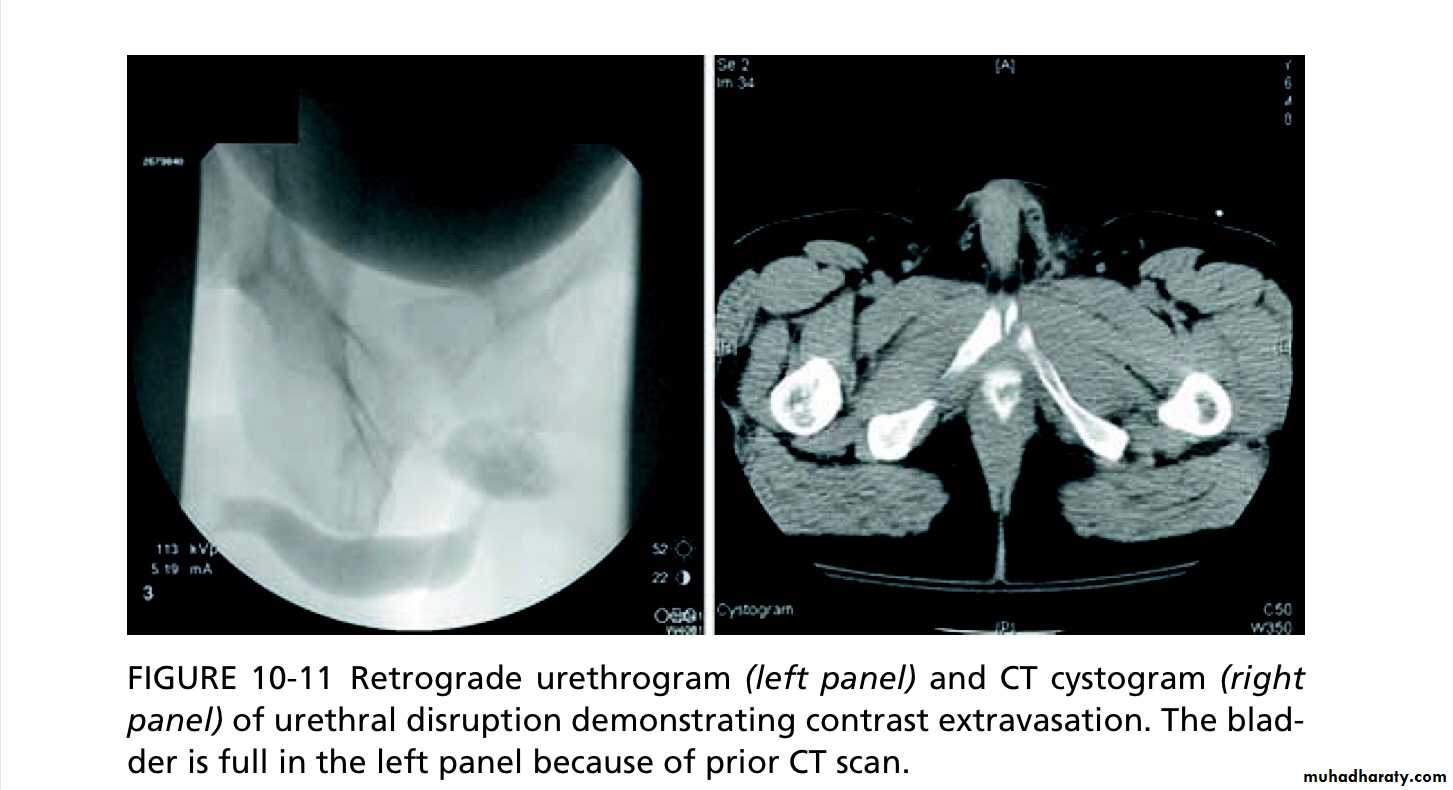

Retrograde cystography or CT cystography

Treatment of bladder rupture:::Extraperitoneal: bladder drainage with a urethral catheter for 2 weeks followed by a cystogram to confirm the perforation has healed.

Indications for surgical repair of extraperitoneal bladder perforation:

1-If you have opened the bladder to place a suprapubic catheter for aurethral injury.

2-A bone spike protruding into the bladder on CT.

3- Associated rectal or vaginal perforation. - Where the patient is undergoing open fixation of a pelvic fracture, the bladder can be simultaneously repaired.

Intraperitoneal: usually repaired surgically to prevent complications from leakage of urine into the peritoneal cavity.

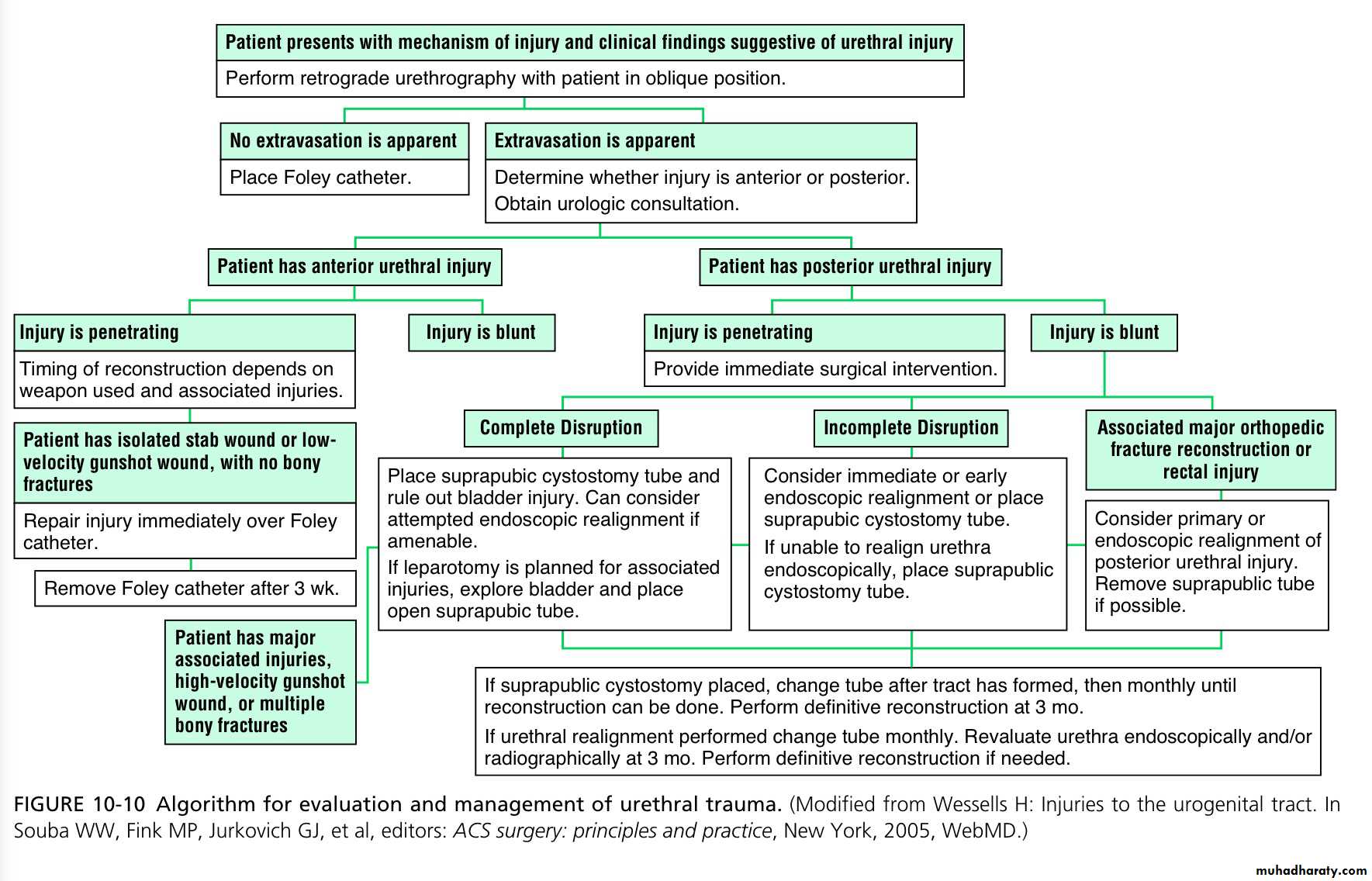

Posterior urethral injuries in males and urethral injuries in females

Mechanisms1-External blunt: pelvic fracture—road traffic accidents, falls from a height, crush injuries—most common cause.

2-External penetrating: gunshot—rare; stab—rare.

3-Internal, iatrogenic: endoscopic surgery; radical prostatectomy; TURP (more likely with vascular prostate, prostate cancer, inexperienced surgeon).

4-Internal, self-inflicted: foreign bodies inserted into urethra—rare.

Symptoms and signs of bladder or urethral injury in pelvic fracture

• Blood at meatus—in 40–50% of patients

• Gross haematuria.• Inability to pass urine.

• Perineal or scrotal bruising.

• ‘High riding’ prostate.

- Inability to pass a urethral catheter.

Retrograde urethrogram:

to detect urethral injury. Some hospitals perform retrograde urethrography only when blood is present at the meatus; others do this in all pelvic fracture patients where the pubic rami have been disrupted.Management of urethral injuries associated with pelvic fractures

Suprapubic catheter: placement via an open approach is generally bet- ter than a percutaneous approach, partly because it allows inspection of the bladder for associated injuries which may require repair, but also because the catheter may inadvertently be placed into the large pelvic haematoma which always accompanies such fractures.Urethral injuries in females

Rare because the female urethra is short and its attachments to the pubic bone are weak such that it is less prone to tearing during pubic bone frac- ture. When they do occur, such injuries are usually associated with rectal or vaginal injuries. In developing countries, prolonged labour can cause ischaemic injury to the urethra and bladder neck, leading to urethrovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula formation.Anterior urethral injuries

1-External blunt: straddle injury (e.g. forceful contact of perineum with bicycle cross-bar*)—most common cause of injury; kick to perineum; penile fracture.2-External penetrating: gunshot; stab.

3- Internal, iatrogenic: catheter balloon inflated in urethra; endoscopic

4- surgery; penile surgery.

5- Internal, self-inflicted: foreign bodies inserted into urethra.

History and examination

The patient usually presents with difficulty in passing urine and frank hae- maturia in the context of a straddle injury. Blood may be present at the end of the penis and a haematoma around the site of the rupture.Confirming the diagnosis and subsequent management

Retrograde urethrography delineates the extent of urethral injury.1-Anterior urethral contusion Typical history:

blood at meatus, no extravasation of contrast on retro- grade urethrogram. Pass a small gauge urethral catheter (12 Ch in an adult) and remove a week or so later.2-Partial rupture of anterior urethra Leak of contrast from urethra with retrograde flow into bladder. Most can be managed by a period of suprapubic urinary diversion.

Give a broad-spectrum antibiotic to prevent infection of extravasated urine and blood.

3-Complete rupture of anterior urethra Leak of contrast from the urethra on retrograde urethrogram, no filling of the posterior urethra or bladder. The urethra may either be immediately repaired (if a surgeon with sufficient experience is available) or an SPC can be placed with delayed repair.

4-Penetrating partial and complete anterior urethral injuries Knife or gunshot wound: primary (i.e. immediate) repair may be carried out if a surgeon experienced in these techniques is available; if not,suprapubic diversion and subsequent repair by an appropriate surgeon.

Immediate surgical repair of anterior urethral injuries is only done in the context of penile fracture or where there is an open wound.